Return to flip book view

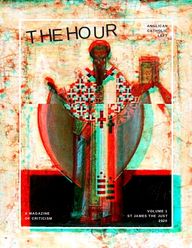

ETHHOURA M A G A Z I N E O F C R I T I C I S MA N G L I C A NC A T H O L I CL E F TV O L U M E 1S T J A M E S T H E J U S T2 0 2 0

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T SP A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , A N D T H E E P I S C O P A L C H U R C HA N G E L N A L U B E G AA N G L I C A N G U I D E T O T H E H O L Y R O S A R Y J A Y A N K O S H Y ( & T H E E D I T O R S )N O T E S O N T H E A E S T H E T I C O F T H E H O U R C A L E B R O B E R T S S T A N L E Y E V A N S : P R O P H E T O F T H E S O C I A L H O P E O F T H E C H R I S T I A N C H U R C HW I L L L E V A N W A YR E L I G I O N I N G E N E R A LT O N Y H U N TS E L E C T I O N S F R O M T H E A C Q U I S I T I V E S O C I E T YR . H . T A W N E Y030921264540

PAULI MURRAY ANTI-BLACKNESSAND THEEPISCOPALCHURCHBy Angel Nalubega

and one of bread and wine and childhooddreams.I would often attend services with myfamily at either my local Catholic school ora parish that had a primarily African(specifically Ugandan and Kenyan)congregation. The differences betweenthe restrained smiles, lackluster attemptsat passing the peace, and the short 10-minute homilies at the former and thebright, joyous, gospel-esque forms ofAfrican worship spaces were massive.Sometimes I couldn’t understand thedissonance.As I grew up, I became acutely aware ofmy uniqueness within the church. As agirl, I was often discouraged from askingtoo many questions about theology, and Iwas often chided for my precociousness.As a teenager, I became disillusioned withthe limited roles for women in the churchand grew frustrated after realizing thatwomen could not become priests. Aftertimes of devastating loss, namely thedeath of my grandmother, I drifted awayfrom the church.Which brings me back to the dog-earedcopy of the Marx-Engels Reader, andSong in a Weary Throat, in its originaledition. I was grabbing a cup of coffeewhen I passed a Housing Works inManhattan. I stepped inside to peruse thebooks. I stumbled across that bright red 0 4P A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , & T E CT H E H O U RI first discovered Pauli Murray in thestacks of a Housing Works in New YorkCity. Her autobiography, Song in a WearyThroat, was tucked under a dog earedcopy of a red Marx-Engels Reader. I didn’tknow it yet, but both of those books wouldserve as a compass towards not onlygreat political development in my life butalso help me navigate questions aroundBlackness in the Episcopal tradition thatI’ve called home within the last two years.I grew up as a Roman Catholic blackchild, who went to catholic schools withblack and white students, but I was oftenthe only black and catholic studentattending. I was raised by a very devoutCatholic grandmother who, in addition tonaming all of her 12 children after saints,raised me with a daily discipline of prayer.Novenas and twice-weekly Mass was thenorm in my household of my mother,grandmother, and me. I was exposed tothe wonder of the Sacraments at an earlyage. I didn’t understand why, but I hadmany questions and a love for theEucharist. I loved knowing exactly what toexpect at Mass: the standing, kneeling,crossing oneself; the bodily movementsanchored me in this knowing of somethinglarger than myself was occurring in thisstrange space. The large crucifix of a manwho I did not yet know would keep methinking of what it exactly meant to behuman. Above all, receiving the Eucharistfelt like I was in two worlds -- one of God

with this woman, person, being, saint -- ina way I couldn’t identify with others.Pauli was raised in the Episcopal Church,whereas I found it in my early 20s. I foundthe Church at a time in my life where Ithought God didn’t love me. I was burntout from organizing and it felt like theEpiscopal tradition was what I needed.Pauli Murray’s early twenties and beyondended up being taken up by social justicework. Pauli committed herself to the laborof social justice, becoming a communityorganizer for the case of Odell Walker, aproject that pushed her into the fold of thecivil rights struggle for years to come. Imyself became politically active after themurder of Michael Brown by Fergusonpolice. Our paths are different, yet similar.Pauli Murray is one of those public figuresthat truly inspire the world. She described,years before the term “intersectionality”was coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, theunique experience of “Jane Crow.” Blackwomen have historically beendiscriminated against not just for theirrace, but also for their gender. Pauli knewthis intimately and articulated it while inattendance at Howard University LawSchool.As a Black woman in the EpiscopalChurch, I have experienced manymicroaggressions, frequently racist0 5P A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , & T E CT H E H O U RMarx-Engels Reader and marveled at thebold lettering and the size of the thing. Idecided to pick it up, and beneath it wasSong in a Weary Throat: An AmericanPilgrimage. It was written posthumously. Idecided to purchase both.I devoured Pauli Murray’s autobiographyon the subway ride home. I resonated withPauli’s life experiences, especially herchildhood -- it was very chaotic, beingraised by her Aunt Pauline, her namesakeand her grandparents. I myself was raisedby my grandmother, and extended familyhad a major part to play in my upbringing.Pauli and I are quite similar, both veryweak children, but very stubborn andshared a love of books. Pauli readeverything and threw herself intoactivities. She always wanted to be thehead of things. She describes herself asfollows: "I was an all-around athlete, I was theeditor in chief of the high schoolnewspaper, I was a member of thedebating club, I was involved in mostof the things that kids are involved in. Ienjoyed doing these things, butunderneath I hated segregation sothat all I wanted to do was to get awayfrom segregation."I grew up in poor Black working-classneighborhoods, and I insisted on doingwell in school because I saw that as myway out into a better, more stable life. Themore I read, the more I started to identify

and even jailed. We work for revolutionknowing that we might not live to see it.Pauli Murray worked diligently throughouther life for a justice that she did not live tosee. I recognize that although Pauli and Idisagree on methods of social change, weboth understand that the journey towardsjustice is long and filled with obstacles.And yet, we believe in a God thataccompanies us on that journey.Black people are part of the Churchbecause we are a creation of God. Wedeserve to be loved and respected asfellow children of God. Our God, asJames Cone writes, is a “God of theOppressed.” Through the struggles thatBlack people in this country and in theAfrican diaspora have undergone, ourGod stays with us. At times it feels like theChurch only wants us around when it’sconvenient. Even though we have aPresiding Bishop, Michael Curry, who isBlack, representation isn’t enough. Blackpeople who live their lives at the marginsare prayerful witnesses to the Gospel, nottokenized symbols of an “inclusive”church. It is a matter of how do we valuethe Black people in our parishes? How dowe treat them as our neighbors, friends,the beloved family of God?The Episcopal Church has a history thathas historically been aligned with power.It’s the Church of presidents andslaveowners, but it is also the Church of 0 6P A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , & T E CT H E H O U Rremarks, and isolation. Our Church isknown for its inclusivity but it is only to apoint. We use the LEVAS Hymnal onlyduring Black History Month. We mentionBlack saints only during the month ofFebruary. Our churches tend to cater tothe white, rich, and elderly. At times itfeels as if there is no place for me. I lovethis tradition. I love the prayer book. Idislike the discrimination that I and othersfrom marginalized backgrounds have hadto undergo. It is hard to speak truth topower, and it is even harder to patternyour life as one who fights for justice evenwhen it is difficult.I mentioned the Marx-Engels Readerearlier. The words of Marx and the wordsof Murray don’t actually differ all thatmuch. They both discuss inequities insociety, and provide a lens through whichto encounter the world. I identify as aBlack, Marxist-Leninist Christian becauseI am committed to the struggle for justiceand freedom for all peoples. I see theGospel and dialectical materialism aslenses through which we encountersomething larger than ourselves, whichpropels us towards a place of freedom.Black people have constantly had to fightto be recognized and valued by society.We have had to organize ourselves,boycott, start movements in order for us toget even a modicum of rights. Our leadershave been assassinated and harassed

daily lives. It’s not easy, and I strugglewith it myself. But our predominantly whiteparishes don’t seem to do this. Racialreconciliation is more than just “doingcommunity outreach when it is beneficial”or “reading Ta-Nehisi Coates Between theWorld and Me for a book club and yet nottalking to the two Black parishioners inyour church.” It isn’t enough to be anti-racist, but we must be accomplices in thestruggle against racism. I wonder whatour churches would be like if theyconfronted the anti-blackness that theyperpetuate in favor of living into theGospel of Jesus Christ and the greatestcommandment.Even Pauli Murray, as accomplished asshe was, who got sainted rather recentlyis still the subject of controversy over hersainthood in the Episcopal Church. Someclergy believe that she shouldn’t beincluded on account of the 50 yearmoratorium on the addition of people tothe sanctoral calendar -- whichautomatically seriously lessens the pool ofsaints and blessed people to a mostlywhite, male, heterosexual pool of people.Even after the grave, Black people still arenot valued in the church.I’ve gotten to a point where I’m learningthat I need to value myself and what Ibring to the Church despite thecontinuous struggles I’ve gone through inthe past two years in the Episcopal 0 7P A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , & T E CT H E H O U Rlaborers, immigrants, and working classpeople. It’s a place where experiencesand identities converge. It is a placewhere many historically blackcongregations are closing, while whiteparishes have millions in endowments. Itis a place where some people areperfectly content with the status quo, andwhere some people are prayerfullyfighting for justice in an unjust world. Wecannot have a beloved community if wecannot reckon with the reality of theChurch, and the inequities present.The organizer, the lawyer, Saint PauliMurray was one who challenged thestatus quo in favor of a more equitablefuture for Black people and women of allbackgrounds. She tirelessly fought backagainst the system. Even though later inlife, she became more mainstream andnot as radical as I suppose I think myselfto be, she never forgot the work she did,and why she did it.The thing I love about Pauli Murray is thather sermons really touch on the key partsof the Christian life but in very direct ways.She wasn’t beating around the bush. Paulipreached often on the necessity of lovingone’s neighbor. The golden rule,encompassed in Matthew 7:12, says “Ineverything do to others as you would havethem do to you; for this is the law and theprophets.” and yet we, being sinners,continuously struggle to do this in our

That passage speaks to why I am still inthe church. Despite the pain, the anti-blackness, and the struggle of isolation, Imust love and nourish myself, andunderstand my role as God’s own. God isworking in me, and God is working inevery church, no matter the congregation.The love of God is deep and broad andmy prayer is that we can prayerfully worktowards a radically loving and unitedchurch.Over the past few months of Black deathand mourning and the rise of uprisingsagainst police violence, I have beenpraying on Romans 8: 12-39. This versekeeps me steadfast in faith despite acapitalistic, anti-black society that wouldrather see me and those I hold dear dead.St. Paul writes, “If God is for us, who isagainst us? He who did not withhold hisown Son, but gave him up for all of us, willhe not with him also give us everythingelse?” Even as our world falls apart, I praythat any forces of evil, hatred, and worksof oppression fall before the mighty loveof God found in Christ Jesus.Angel NalubegaPhiladelphia, PA0 8P A U L I M U R R A Y , A N T I - B L A C K N E S S , & T E CT H E H O U RChurch. I must have faith that even here,where I’m often isolated, God is stillpresent in me as much as He is present inothers.One of my favorite sermons by PauliMurray is titled “The Second GreatCommandment.” She gave thiscommandment at the Epiphany Parish inWinchester, MA on November 21, 1976.This passage articulates her theologyquite well. “Pivotal to my relatedness toGod, on the one hand, and to myneighbor, on the other, is my relationshipto myself. Unless I love and acceptmyself, I am not free to love and acceptmy neighbor.” Loving myself in thiscontext simply means self-respect, a self-regard born of the realization that I am theobject of God’s limitless love and mercy,part of God’s creation. Self-acceptancedoes not mean uncritical self-approval, butself-understanding, awareness of mystrengths and weaknesses, and theblessed assurance that God-in-Christ isworking in me and through me toward theperfection of my life. When I can believe,as St. Paul did, that “neither death nor life,nor angels, nor principalities, nor thingspresent, nor things to come, nor powers,nor height, nor depth, nor anything else increation, will be able to separate us fromthe love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” Iam liberated from self-preoccupation thatblocks my capacity to care for others.

AnglicanGuideTo theHolyRosaryNo one expects the anglo-catholicinquisition. Yet not long after starting amagazine working from that tradition webegan receiving emails and messagesasking about things like apostolicsuccession and praying the rosary. Thetruth of the matter is, I am not a very goodAnglo-Catholic with respect to piety. I wasa Pentecostal before I becameEpiscopalian and I intentionally sought outthe most evangelical parish in the citywhen I finally did switch teams. Thisdiocese as a whole is comfortably broadand low in churchmanship and while a fewheady places make occasional use ofincense, Minnesota is not known forelaborate ceremony or widespread mariandevotion. I don't think I've seen more thantwo candlesticks on an altar around here.You can surmise that I am not a reliableperson to ask for advice on praying theRosary. And yet enough people haveasked about it that it almost felt cruel to continually shrug and confess myignorance. There is a perceived need forsuch resources, and by gosh, our DIYspirit was roused to action. But if I wasgoing to put my hand to the plow, I wasgoing to find a way to integrate our aidswith Anglicanism.Now there is no "Anglican way" to praythe rosary. The so-called "AnglicanRosary" maybe a helpful way for somepeople to pray, but it is not the same thingas the traditional rosary. So we will notcover that here.But it is not uncommon for people to useScripture or additional prayers to aid inpraying the rosary. I wondered to myself:What if I were to design a booklet thatused collects from the (1979) Book ofCommon Prayer, and thematicallyorganized scriptural passages to help?Roman Catholic resources, while 0 9T H E H O U R

6 - Ten Hail MarysWhen finishing: Hail, Holy Queen. Then the Sign ofthe Cross & "Inthe name of theFather, & of theSon, & of the HolySpirit"1 - The Sign of the Cross, & The Apostle's Creed5 - Announce the firstMystery & Our FatherAnnounce the next Mystery, &Our Father2 - Our Father3 - Three Hail Marys4 - Glory BeA "Decade"Glory Bewith formatting an introductory essay byJayan Koshy, a member of the Sodality ofMary, which is included below. I hope thatthis project will help people enter morefully into contemplation on the life ofChrist, told by way of his Holy Mother.Nota Bene: Read the squares top left totop right; bottom left, then bottom right.I N T R O T O T H E R O S A R Yexceptionally helpful, often use ahodgepodge of translations, few of whichare standard in Anglican contexts; and thesyntactical registers often fluctuate wildlyfrom contemporary to jacobean. What Ifelt was needed was conformity acrossthe board. Utilizing scriptural passagesshared with me by Jayan Koshy, I decidedon three rules.1) Whenever possible, use collectsstraight from the prayer book.2) For Rite I language use only theAuthorized Version; for Rite II, the NRSV.3) Where there was overlap between rule1 and 2, always prioritize the BCPtranslation.My reasoning behind the third rule wasthe recognition that if an Anglican has theMagnificat memorized, they will have itfrom praying the Daily Office in the BCP.It's a simple matter of giving first positionto memorization over absolutetranslational consistency.Anglicans deserve our own kitschydevotional material. To that end we willinclude images, but give them The Hourtwist. The scope of the project has quicklygotten out of hand. With the full force ofthe semester upon me, my "free time" hasdried up. Thus I have only been able tofinish the Joyful Mysteries in Rite I, along 1 0T H E H O U R

1 1T H E H O U RPrayed by Roman Catholics and manyAnglicans/Episcopalians, the Rosary isa non-liturgical devotion that meditateson the life of Christ through the eyes ofhis mother, the Blessed Virgin Mary. Itmakes use of three main prayers (OurFather, Hail Mary, and Glory Be) asaids to meditation. The Rosary is structured around“Mysteries,” which are moments in thelife of Christ/Mary that reveal deepspiritual truths. There are 4 sets of 5Mysteries (for a total of 20):- The Annunciation: When the AngelGabriel told Mary she would givebirth to Jesus- The Visitation: When Mary visited hercousin Elizabeth (John the Baptist'sMother)- The Nativity: Christmas! When Marygave birth to Jesus- The Presentation: When Mary and Joseph brought Jesus to thetemple to dedicate him- The Finding of Jesus in the Temple:When Mary and Joseph lost Jesusbut found him in the templeteaching the elders- The Baptism of the Lord: When Jesuswas baptized by John and revealedas God’s Son- The Wedding at Cana: When Jesus turned the water into wine- The Proclamation of the Kingdom: When Jesus first proclaimed thatthe Kingdom of God was at hand- The Transfiguration: When Jesus wasrevealed to three disciples in hisdivine majesty- The Last Supper: When Jesus instituted the Holy Eucharist- The Agony in the Garden: WhenJesus wept in the Garden ofGethsemane- The Scourging at the Pillar: WhenJesus was whipped by the Romanguards- The Coronation with Thorns: WhenJesus was crowned with a wreathof thorns- The Way of the Cross: When Jesuscarried his cross to Golgatha- The Crucifixion of our Lord: WhenJesus was killed on the Cross

1 2T H E H O U R- The Resurrection of our Lord: Easter!When Jesus rose from the dead- The Ascension of our Lord: WhenJesus returned bodily to the Fatherin Heaven- The Descent of the Holy Spirit: WhenGod sent the Holy Spirit to theChurch at Pentecost- *The Assumption of the BlessedVirgin*: When Mary was taken up bodily into Heaven- The Coronation of the Queen of Heaven: When Mary, representingthe Church, is crowned as theQueen of heaven, the pinnacle ofGod's creation*not all Episcopalians believe in this,but most Anglo-Catholics do. TheEpiscopal Church does, at any rate,maintain the feast day as St. Mary theVirgin.Each of these mysteries iscontemplated as you pray a “decade” ofthe Rosary. A decade is the basic unitof the Rosary; it consists of: 1 - Our Father10 - Hail Marys1 - Glory BeYou will find these prayers in thispamphlet.You can pray one decade (for oneMystery) or even 20 (for all of them),but usually, people pray a different setof Mysteries each day. Typically theyfollow this pattern, but you’re not boundto it:Sometimes it’s helpful (especially whenstarting out) to use Scripture verses tohelp you focus on the Mysteries athand. A "Scriptural Rosary" is includedin this pamphlet.To start the Rosary:- Sign of the Cross - Apostles Creed - Our Father (x1) - Hail Mary (x3) - Glory Be (x1) ("In the name of...)("I believe in God...)("Our Father in...)("Hail Mary, full of...)("Glory be to the ...)Sunday: Monday: Tuesday: Wednesday: Thursday: Friday: Saturday: Glorious MysteriesJoyful MysteriesSorrowful MysteriesGlorious MysteriesLuminous MysteriesSorrowful MysteriesJoyful Mysteries Then pray however many decades ofthe Rosary you want or have time for.Announce the Mystery and spend sometime thinking about it & what God issaying to you in it before you start theHail Marys. When you’ve finishedpraying the decade(s) you intend to,you resolve with a hymn to Mary calledthe Salve Regina or Hail Holy Queen.Close with the Sign of the Cross in thename of the Father, and of the Son,and of the Holy Spirit.For some who come from Protestantbackgrounds, praying the Rosary mayseem strange, confusing, or eventroubling. Are we praying to Maryinstead of God? Why does Mary featureso prominently in a devotion that’sabout Jesus?

1 3T H E H O U RWhile most Protestants tend to think ofMary as an ordinary Christian after theReformation, since the earliest days ofthe Church, Mary has been given aparticularly high seat of honor becauseof her unique role in the Incarnation.There’s a staggering variety of imagesand metaphors used to talk about her,but they all revolve around once centraltruth: Mary, in saying “Be it unto meaccording to your will,” became thevehicle for God to become human fleshin this world.For this reason, Mary has been seen asa key participant in the Incarnation–without her the Word would not havebecome flesh; and she’s been seen asa type, or image, of the Church. Thishas led the Church to see her asparticularly meriting devotion: as wecome closer to Mary, she points usmore powerfully and more intimatelyto her Son, the object of our worship.The Rosary builds on this idea thatMary is a helper or aid in strengtheningour relationship with Christ. Just as theChurch gives us a framework forunderstanding the wonder of theIncarnation, the Rosary invites us totake Mary’s vantage point as a spiritualaid in understanding God’s saving workin Christ. Mary is not the object of ourworship but rather the most brilliantsignpost pointing us to the object of allworship.I believe in God, the Father almighty,maker of heaven and earth;And in Jesus Christ his only Son ourLord; who was conceived by the HolyGhost, born of the Virgin Mary,suffered under Pontius Pilate, wascrucified, dead, and buried. Hedescended into hell. The third day herose again from the dead. Heascended into heaven, and sitteth onthe right hand of God the Fatheralmighty. From thence he shall cometo judge the quick and the dead.I believe in the Holy Ghost, the holycatholic Church, the communion ofsaints, the forgiveness of sins, theresurrection of the body, and the lifeeverlasting. Amenwho art in heaven,hallowed be thy Name,thy kingdom come,thy will be done,on earth as it is in heaven.Give us this day our daily bread.And forgive us our trespasses,as we forgive those whotrespass against us.And lead us not into temptation,but deliver us from evil.

1 4T H E H O U RHail Mary, full of grace,the Lord is with thee.Blessed art thou among women,and blessed is the fruit of thywomb, Jesus.Holy Mary, Mother of God,pray for us sinners,now and at the hour of our death.AmenGlory be to the Father, and to the Son,and to the Holy Ghost: as it was in thebeginning, is now, and ever shall be,world without end. AmenHail! Holy Queen, Mother of mercy, our life,our sweetness, & our hope. To thee do wecry, poor banished children of Eve. To theedo we send up our sighs, mourning andweeping in this vale of tears. Turn, then,most gracious advocate, thine eyes ofmercy toward us. And after this, our exile,show unto us the blessed fruit of thy womb,Jesus. O clement, O loving, O sweet VirginMary.Pray for us, O holy Mother of God,That we may be made worthy of thepromises of Christ.O God, whose only begotten Son by his life,death, and resurrection has purchased forus the rewards of eternal life; grant, webeseech thee, that by meditating uponthese mysteries of the Most Holy Rosary ofthe Blessed Virgin Mary, we may imitatewhat they contain and obtain what theypromise, through the same Christ our Lord.AmenThe following collects andScripture passages are providedas aids to meditation. You maypray the collect when youannounce the mystery; then set anintention, if you have one, for thedecade before you proceed. Youmay read a verse with each of theten Hail Marys in a decade.

1 5T H E H O U RWe beseech thee, O Lord, pour thygrace into our hearts, that we whohave known the incarnation of thy SonJesus Christ, announced by an angelto the Virgin Mary, may by his crossand passion be brought unto the gloryof his resurrection; who liveth andreigneth with thee, in the unity of theHoly Spirit, one God, now and for ever.Amen.-1. "The angel Gabriel was sent fromGod to a virgin; and the virgin's namewas Mary" 2. "Hail, thou that art highly favored.Blessed art thou among women" 3. "When she saw him, she wastroubled at his saying, and cast in hermind what manner of salutation thisshould be" 4. "And the angel said unto her, Fearnot, Mary: For thou hast found favorwith God" 5. "Behold, thou shalt conceive in thywomb, & bring forth a son, and shaltcall his name Jesus" 6. "He shall be great, and shall becalled the Son of the Highest: and ofhis kingdom there shall be no end 7. "Then said Mary unto the angel,'How shall this be, seeing I know not aman?" 8. "The Holy Ghost shall come uponthee, and the power of the Highestshall overshadow thee" 9. "Therefore also that holy thing whichshall be born of thee shall be called theSon of God" 10. "Behold the handmaid of the Lord;be it unto me according to thy word"

1 6T H E H O U RFather in heaven, by whose grace thevirgin mother of thy incarnate Son wasblessed in bearing him, but still moreblessed in keeping thy word: Grant uswho honor the exaltation of herlowliness to follow the example of herdevotion to thy will; through the sameJesus Christ our Lord, who liveth andreigneth with thee and the Holy Spirit,one God, for ever and ever. Amen-1. "Mary arose in those days, and wentinto the hill country...and entered intothe house of Zacharias, and salutedElizabeth" 2. "When Elisabeth heard thesalutation of Mary, the babe leaped inher womb; and Elisabeth was filledwith the Holy Ghost" 3. "And she spake out with a loud voice, and said, Blessed art thouamong women, and blessed is the fruitof thy womb" 4. "And blessed is she that believed:for there shall be a performance ofthose things which were told her fromthe Lord" 5. "And Mary said, My soul dothmagnify the Lord, and my spirit hathrejoiced in God my Savior. For he hathregarded the lowliness of hishandmaiden" 6. "For behold from henceforth allgenerations shall call me blessed. Forhe that is mighty hath magnified me,and holy is his Name" 7. "And his mercy is on them that fearhim throughout all generations" 8. "He hath showed strength with hisarm; he hath scattered the proud in theimagination of their hearts" 9. "He hath put down the mighty fromtheir seat, and hath exalted the humbleand meek"10. "He hath filled the hungry withgood things, and the rich he hath sentempty away. He remembering hismercy hath holpen his servant Israel,as he promised to our forefathers,Abraham and his seed for ever"

1 7T H E H O U RAlmighty God, who has given us thyonly-begotten Son to take our natureupon him, and as at this time to beborn of a pure virgin: Grant that we,being regenerate and made thychildren by adoption and grace, maydaily be renewed by thy Holy Spirit;through the same our Lord JesusChrist, who liveth and reigneth withthee and the same Spirit ever, oneGod, world without end. Amen.-1. "And so it was, that, while they werethere, the days were accomplishedthat she should be delivered" 2. "And she brought forth her firstbornson, and wrapped him in swaddlingclothes and laid him in a manger;because there was no room for themin the inn" 3. "And there were in the same countryshepherds abiding in the field, keepingwatch over their flocks by night" 4. "And, lo, the angel of the Lord cameupon them, and the glory of the Lordshone round about them: and theywere sore afraid" 5. "And the angel said unto them, Fearnot: for, behold, I bring you goodtidings of great joy, which shall be to allpeople" 6 "For unto you is born this day in thecity of David a Savior, which is Christthe Lord" 7. "Glory be to God on high, and onearth peace, good will towards men" 8. "There came wise men from theeast...and when they were come intothe house, they saw the young childwith Mary his mother" (Matt 2.1;11)9. "and they fell down, and worshippedhim: they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense, and myrrh"(Matt 2.11)10. "But Mary kept all these things, andpondered them in her heart"

1 8T H E H O U RAmighty and everliving God, wehumbly beseech thee that, as thy only-begotten Son was this day presentedin the temple, so we may be presentedunto thee with pure and clean heartsby the same thy Son Jesus Christ ourLord; who liveth and reigneth with theeand the Holy Spirit, one God, now andforever. Amen.-1. "They brought him up to Jerusalem,to present him to the Lord; as it iswritten in the law of the Lord" 2. "And, behold, there was a man inJerusalem, whose name was Simeon;and the same man was just anddevout, waiting for the consolation ofIsrael: and the Holy Ghost was uponhim" 3. "And it was revealed unto him by theHoly Ghost, that he should not seedeath, before he had seen the Lord'sChrist" 4. "And when the parents brought inthe child Jesus...then took he him up inhis arms, and blessed God" 5. "Lord, now lettest thou thy servantdepart in peace, according to thy word" 6 "For mine eyes have seen thysalvation, which thou hast preparedbefore the face of all people" 7. "To be a light to lighten the Gentiles,and to be the glory of thy people Israel" 8. "And Simeon blessed them, andsaid unto Mary his mother, Behold, thischild is set for the fall and rising againof many in Israel; and for a sign whichshall be spoken against" 9. "(Yea, a sword shall pierce throughthy own soul also,) that the thoughts ofmany hearts may be revealed" 10. "They returned into Galilee, to theirown city Nazareth. And the child grew,and waxed strong in spirit, filled withwisdom: and the grace of God wasupon him"

1 9T H E H O U RBlessed Lord, who has caused all holyScriptures to be written for our learning:Grant that we may in such wise hearthem, read, mark, learn, and inwardlydigest them, that, by patience andcomfort of thy holy Word, we mayembrace and ever hold fast the blessedhope of everlasting life, which thou hastgiven us in our Savior Jesus Christ;who liveth and reigneth with thee andthe Holy Spirit, one God, forever andever. Amen.-1. "When Jesus was twelve years old,they went up to Jerusalem after thecustom of the feast" 2. "And when they had fulfilled thedays, as they returned, the child Jesustarried behind in Jerusalem; andJoseph and his mother knew not of it" 3. "And when they found him not, theyturned back again to Jerusalem,seeking him. " 4. "And it came to pass, that after threedays they found him in the temple,sitting in the midst of the doctors, bothhearing them, and asking themquestions"5. "And all that heard him wereastonished at his understanding andanswers. And when they saw him, theywere amazed:" 6 "And his mother said unto him, Son,why hast thou thus dealt with us?Behold, thy father and I have soughtthee sorrowing" 7. "How is it that ye sought me? Wistye not that I must be about my Father'sbusiness?" 8. "And they understood not the sayingwhich he spake unto them" 9. "And he went down with them, andcame to Nazareth, and was subject unto them...And Jesus increased inwisdom and stature, and in favor withGod and man 10. "But his mother kept all thesesayings in her heart"

SAINT JAMESTHE JUSTSAINT JAMESTHE JUST

THE AESTHETIC of this magazine, noless than its content, was of crucialimportance from the very firstconversations Tony and I had about it. Atthe start, we knew that we didn’t want toproduce yet another “church blog” and thismeant that we would have to resist notonly the predictable sermonizing of whichwe had grown so tired, but also thefamiliar stock images of cathedrals andsacred wares that typically adorned suchpublications. What’s more, since weestablished our editorial trajectory in thetradition of the Anglican Left as developedin the late 19th and early 20th centuries,we were well aware of how easy it wouldbe for our stylistic choices to suggest aboutique and reactionary nostalgia thatwould undermine our criticism. And so wedrew visual inspiration from sources aswide-ranging as Art Nouveau, the DIYpunk zines of the 80s and 90s, obscureBut because these things have been shifted, because the natural continuities within whichthey normally exist have been broken, and because they have now been arranged totransmit an unexpected message, we are made conscious of the arbitrariness of theircontinuous normal message. Their ideological covering or disguise, which fits them so wellwhen they are in their proper place that it becomes indistinguishable from theirappearances, is abruptly revealed for what it is. Appearances themselves are suddenlyshowing us how they deceive us.-- John Berger, “The Political Uses of Photo-Montage.”“...the only sure fact is ceaseless flux….” -- Vida Dutton Scudder.THETHETHE T H E H O U R2 1B Y C A L E B R O B E R T SB Y C A L E B R O B E R T SB Y C A L E B R O B E R T STHE HOURTHE HOURTHE HOUR NOTES ONNOTES ONNOTES ON THETHETHEAESTHETICAESTHETICAESTHETICOFOFOFT H E H O U R

2 2T H E H O U Rfilm posters from Eastern Europe in the60s, the Vienna Secession, and theimpeccable austerity of the midcenturybook covers put out by McGraw-Hill. Ourintent was that all of these referenceswould converge in order to present aconscious modernism in the best sense ofthe word.But the modernist aesthetic that pervadesour pages is not so separable from thecontent as to be merely a “style” that wehappen to like (though we do have ashameless affection for it). Our wholeproject is one of recovery -- both ofaesthetics and of thought. The figures thatwe consider our greatest influences werethoroughly modernist in their methods --this much is clear. But most are at least acentury in the past and can seem distantlyremoved from our present context. Theirbooks are long out of print andcontemporary secondary literature isscarce to non-existent. Between us andthem, there is something like a chasm,and not just in history, but in the veryconsciousness of our church. They are,for all intents and purposes, irrelevant --and the fact that we acquire so much oftheir material from random pdf scans inthe public domain proves the point. Again,our project is one of recovery.But what does it mean to recovermodernism? The mere suggestion of sucha project is at risk of a basic contradiction.If, as Marshall Berman wrote, “to bemodern is to be part of a universe inwhich, as Marx said, ‘all that is solid meltsinto air,’” [1] then we are very much still inmodernity. Where then is this vantagepoint supposed to be located from whichmodernism could be recovered? Granted,the artistic movement of modernism isgenerally considered to be something thathas already run its course, having sincebeen succeeded by something else. And,as already mentioned, the intellectualmovement we draw from most directly islikewise mostly consigned to the past.There is thus an added risk of indulging inmere antiquarianism; a presumption ofindifference that allows one to look backon the past with nostalgic curiosity.Fredric Jameson describes this risk withpenetrating insight in his distinctionbetween pastiche and parody. He says:Pastiche is, like parody, the imitationof a peculiar or unique style, thewearing of a stylistic mask, speech, ina dead language: but it is a neutralpractice of such mimicry, withoutparody’s ulterior motive, without thesatirical impulse, without laughter,without that still latent feeling thatthere exists something normalcompared with which what is beingimitated is rather comic. (emphasishis) [2] That last line is key: pastichepresupposes that what it imitates is no

2 3T H E H O U Rlonger a present reality, and thus that itmakes no contribution to the constructionof the present reality as it is or as it couldbe. The detachment from the pastironically obscures the contingency of thepresent, which is why pastiche is soindicative of both the culture of latecapitalism and, oddly enough, theaesthetics of reaction. Change dependsupon contingency, and “...in a world inwhich stylistic innovation is no longerpossible, all that is left is to imitate deadstyles, to speak through the masks andwith the voices of the styles in theimaginary museum.” [3] Any project ofrecovery such as ours must somehowovercome this challenge.When I think about the present reality ofthe Episcopal Church, what stands out inparticular is exactly this kind of pastiche.We are at our own End of History, itseems, and I’m not just talking about ourterminal decline. Consider the various“church parties” that historicallydetermined the local idiosyncrasies ofliturgy and devotion that were radicallyneutralized by the 1979 Book of CommonPrayer. One can see an analogy betweenthe sincerity of the old rivalries betweenAnglo-Catholics and the Low-Churchcrowd and the “ulterior motive” thatJameson identifies in parody: not only dideach side satirize the other, but they didso out of the “latent feelingthat...something normal” existed againstwhich both they and their rivals could bedefined. But now, long after the revolutionof the Liturgical Movement, that “latentfeeling” is all but gone. The impressiveminimalism of our current Prayer Book,however commendable, has inadvertentlyproduced a kind of stasis in theconsciousness of our church; and with it,a corresponding “disappearance of asense of history” [4] that, for Jameson,defines the late capitalist condition. Andthis holds for both the aesthetics of ourliturgy and the state of our intellectual life.After all, what is Weird Anglican Twitter ifnot an ironic celebration of this pastiche?We don’t so much inhabit an identifiablepresent as what is rather a supposedlyneutral realm that is beyond history itself.And, to be clear, this is just as much thecase for those who fetishize the return tosome imagined Real Anglicanism™ as it isfor those who would endlessly improvisethe liturgy to keep up with their solipsism.Both presuppose an evacuated present inwhich we are fundamentally disinterestedspectators who only become invested byan act of preference.In spite of these challenges, I wouldsuggest that what we are recovering atThe Hour is itself part of the reason thatthis magazine is capable of overcomingthese challenges. We are out to recover aspecific kind of modernism -- themodernism of the Anglican Left -- and thefact that we have to recover it at all saysmore about the false presumptions of ourpresent moment than it does about its

2 4T H E H O U Rsupposed loss to the past. Those weconsider our heroes -- Vida DuttonScudder, Percy Dearmer, StewartHeadlam, et al -- looked out on a world inwhich all that was solid was melting intoair… and it’s still melting. That world, theworld imposed by capitalism, is the“something normal” with which we cancompare ourselves. And with regard toour aesthetic, it’s far from being anexercise in pastiche simply because itreferences the past. Which brings us backto the quote from the inimitable JohnBerger at the beginning of this essay.In context, Berger is analyzing the work ofthe German artist John Heartfield, knownfor his use of photo-montage to makevisual art that was explicitly anti-fascist.But Berger proceeds to describe the wayin which the political statement of his workwas somehow embedded in the verymedium of photo-montage itself. Like ourintent with The Hour, the form in whichHeartfield presented his message was notseparable from the message, as thoughmerely incidental, but rather preceded itand made it possible. By “shifting” thingsaround, by breaking the supposedly“natural continuities” between things aswe normally experience them, photo-montage forfeits its claim to realism andrepresentation in order to depict a truerrealism altogether. It embraces thearbitrary in order to reveal the arbitrary.And in this sense, photo-montage isinconceivable except under capitalism andwithin Walter Benjamin’s “age ofmechanical reproduction.” In short, whenall that is solid melts into air, art can onlyproceed by demonstrating that such is thecase.Coincidentally enough, Berger was writingelsewhere about Benjamin when he saidthat “the antiquarian and the revolutionarycan have two things in common: theirrejection of the present as given and theirawareness that history has allotted them atask.” [5] To the extent that it’s possible tobe both antiquarian and revolutionary, I’dlike to think that these words, along withBerger’s analysis of Heartfield’s photo-montage, get at something important inour project of recovery at The Hour. Thereis obviously “the rejection of the presentas given” which inspired Heartfield’s anti-fascist art and also inspires us to producethis magazine in the manner that we do.But a mere rejection of the present is notenough; by itself, it lacks a sense ofhistory and the task that accompanies it.Our heroes never ascended to thepretenses of universal significance in theeyes of those who came after them. Theysoon became inescapably confined to theparticular times and places in which theylived and thought -- and thus to obscurity.The same can be said for many of theinspirations behind the aesthetic of TheHour. But it is precisely their obscurity thataffords us with the possibility of a freshand radical recovery. Because who letthem become obscure in the first place?

2 5T H E H O U RWhen we cropped that picture of VidaDutton Scudder and placed it alongsidedisparate text and colors, we wereeffectively displaying our whole project ina visual depiction: we can only accesssomeone like her through the fragmentedand arbitrary means of digitalreproduction, so we might as well behonest about it. But once we re-publishher likeness and work in The Hour, wefind that it is presented anew. ContraJameson’s pastiche, innovation all of thesudden is possible, because the peopleand the styles that we are imitating are nolonger dead. They speak again, inwhatever way is possible in thishaphazard little operation, with a voicethat is now confined, inescapably, to ourparticular time and place, as well astheirs. Which is true of every voice. Withthem as our comrades, the continuitiesthat were thought to have been brokenhave been restored, but for the specifictask that has been allotted to us: the taskof recovery and revolution.Caleb RobertsPonca City, Oklahoma[1] Marshall Berman. All That is Solid Melts intoAir: The Experience of Modernity, 15. [2] Fredric Jameson. The Cultural Turn: SelectedWritings on the Postmodern, 1983-1998, 5.[3] Ibid., 7.[4] Ibid., 20.[5] John Berger. Landscapes: John Berger on Art,56.

Prophet of the social hope of the christian churchBy Will Levanway

2 7T H E H O U RSTANLEY EVANS (1912-1965) appearstoday as a rather marginal figure even tomany with an interest in ChristianSocialism. To mention his name to manyin those circles is to bring forth either aknowing smile or a confession ofignorance. Evans, like Alan Ecclestone,worked at a time of transition between themarching optimism of John Groser andthe grassroots organizing of Ken Leech.Groser's association with Socialists andCommunists helped him find anappointment in the East End while Evanswas among a number of clergy blacklistedby Lambeth in the 1950s for the samereason. Evans had trained at Mirfield withthe Community of the Resurrection beforecoming to London to serve a successionof curacies where he quickly becamedisillusioned with the politics of his fellowclergy. His politics during the 1940s meantthat he was able to report on the trial ofCardinal Mindszenty for the CommunistParty of Great Britain's Daily Worker, butwas unable to secure an appointment asan incumbent in the Church of England.Even if he was not a member of the Party,he was enmeshed in its political scene.His sermon at a requiem for Stalin at St.George's, Queen Square in 1953 speaksboth to his refusal to discount theCommunist project at that time as well asto his ambivalence about some of hisstrange comrades. In the interveningyears, Evans appears to have becomedisillusioned by the state of the SovietUnion and in 1965 could describe Stalin's “sub-human ruthlessness.” The failurewas partly an infidelity to Marx, a lack ofawareness of humanity, and a “crudity ofthought” leading to “a cruelty in action.”Out of this time of disillusion, Evanseventually emerged as a successfulparish priest who took services out intothe streets and saw the need to trainworking people for the priesthood. Hebecame a canon of Southwark Cathedralas Southbank Religion was emerging. Hehelped develop a model of theologicaltraining for people unable to leave behindwork to go to a college of any sort. Evansremained radical throughout this timeeven as he shed some of his earliersympathies. He saw, following JackPutterill, the need to closely link theworship, prayer, and devotion of a parishwith its own internal economy of sharing.He took so many attempts to stopChristians from pursuing the discipline ofsharing as so many refusals of genuinediscipleship. For him, the only division inthe Church was between those who knewthe Kingdom of God demanded thetransformation of the world and those whodid not. His great work, The Social Hopeof the Christian Church, forcefully arguesfor the need for this transformation. TheSocial Hope was published the year of hisdeath and stands as a testament of histhought.In this work, he takes up at lengtharguments made earlier in The Church in

2 8T H E H O U Rthe Back Streets, Return to Reality, andChristian Socialism: a Study Outline andBibliography. In it he provides a dialecticalaccount of what he describes as the“social tradition” in Christianity beginningwith Jesus and ending in his present.Influenced by his time amongCommunists, Evans does not take aRomantic view of Church history. He doesnot valorize or glamorize the Middle Ages,viewing them as only marginally betterthan the Reformation. The time whenChristian life was properly shared, whenits unity was manifest, when the faith wastruly preached, was the Apostolic age.The social tradition is the faith of theApostles. To preach the socialimplications of the Gospel is not to addanything to it. The long sections of thebook on Church history are a dialecticalaccount of the emerging, submerging, andrediscovery of this fact of the gospel.Evans' goal in The Social Hope of theChristian Church was to show how thisfact of the Gospel might once again berecovered, how we might return onceagain to the Apostolic faith. Howeverdisillusioned he became with some formsof Communism, Evans remained faithfuland hopeful to the coming of God'sKingdom among us. The true faithremained.In what follows, I am going to try to restatethe heart of Evans’ vision in The SocialHope. Putting to the side his account ofChurch history, I will concentrate on the Kingdom of God in the preaching of theProphets, Jesus, and Paul. Jesus makesa decisive intervention into previousprophetic work. Paul establishes thestrategy and tactics of the new situationfollowing Christ's ascension. The longerhistorical sections of the book detail theattempts of various Christians to avoid orto engage in their contemporary situation.The heart of the work calls us to thatengagement now.Evans builds The Social Hope of theChristian Church around the idea of theKingdom: what it is; how it has beenpursued; how we strive for it today. Hedoes not take up the concept out of anideal curiosity or an academic desire togenerate research. Repeatedly throughoutthe book, Evans returns to the fact -- andhe believes it to be a fact -- that theKingdom is essential to what Christianityis. As he puts it towards the end of thebook: “It is important to grasp the fact thatthis is not something added to Christianityby those who think a particular kind ofway, it is of its essence.” (245) The“social” tradition of Christianity does notcome late to the scene but is preciselyhow Christianity initially appears.The source of this view is, of course, theBible. By “Bible,” Evans does not meanthe text drawn through any number ofcontemporary interpretive schemes or

secured in fundamentalist bulwarks. TheBible we have received conveys acoherent message of God's self-revelationto humanity and the wending ofhumanity's response to that self-revelation. The human response to God'sself-revelation is a way of living together.The composition of the Bible by differenthuman people is evidence of thecoherence of this self-revelation acrosstime. Evans sketches his view of the Bibleto show that his reading is faithful but alsoto show his readers that they too canengage with the Bible as a source of life.He sees parallels between the minuteparsing of Origen and later historical-critical scholars but insists that the primarything is to read the Bible seriously as awhole. He, therefore, places Jesus withinthe twists, turns, and contradictions of theBible as a whole.The social hope pursued by Christians isthe Kingdom of God. The phrase,announced powerfully by Jesus in Mark1:15 -- “The time is fulfilled,and thekingdom of God is at hand: repent ye, andbelieve the gospel,” is a phrase with ahistory. The basic structure of thekingdom exists already in the OldTestament:The law comes about as the Israelitesbecome a people in the desert. Itenshrines the form of their unity. The unityand freedom of this people requires anegalitarian way of life wherein things areshared. The law begins with the idea thatthe land belongs to God rather than beingowned as private property. “Behold, theheaven and the heaven of heavens is theLord’s thy God, the earth also, with all thattherein is.” (Deuteronomy 10.14) Evans isaware, of course, that this egalitarianapproach has often failed. It is unclear, forinstance, if the envisioned regular erasureof debt was ever practiced. Nevertheless,some form of life together based uponsharing was practiced that was capable ofgenerating this law. Even if it was neverfully practiced, the law still announces thisvision for a society that can be pursuedwhere such erasure could be a regular ifnot constant practice.The law points to an ideal pursued in theprogressive discovery of the life andmorality God has intended for God's freepeople. The discovery of the law of theKingdom of God is an ongoing process inthe Bible. The prophets again and againcall people back to the unity of lifeannounced in the law. More than this "This story is, in a sense, the key to the wholeof Hebrew history. Moses is the liberator,the inspired leader who found the way tofreedom, and the law enshrines the way ofliving of those who were slaves but havebecome free. It was not a chain that boundbut a sword that released." (15)2 9T H E H O U R

recollection, though, they continuallypress the implications of God's will for atruly equal society. Evans explains thiscritical function in two ways.First, the prophets resist the impulse tomove the relationship of human beings toGod into a separate “religious” sphere.The attempt to sequester God into areligious sphere, to cordon off worshipfrom life, is moral choice and dereliction ofthe law.Bring no more vain oblations; incenseis an abomination unto me; the newmoons and sabbaths, the calling ofassemblies, I cannot away with; it isiniquity, even the solemn meeting.Your new moons and your appointedfeasts my soul hateth: they are atrouble unto me; I am weary to bearthem. And when ye spread forth yourhands, I will hide mine eyes from you:yea, when ye make many prayers, Iwill not hear: your hands are full ofblood. (Isaiah 1:13-15)Second, the prophets recall their hearersback to this integrated version of life. Theyknew that to abandon this way of the lawwas to court destruction. “For they havesown the wind, and they shall reap thewhirlwind.” (Hosea 8:7) God's concern iswith the morality of the community as awhole, and so they must be recalled as awhole or they will fall as a unit. Evansgoes on at length to show how this "For them as for the prophets the greatconsuming interest of life and of itsfuture was the Kingdom of God and theMessiah comes into the picture only inconnection with the Advent of theKingdom. That the coming of the Kingdominvolved struggle they never doubted andthe real point of division between thegeneral aspirations of the people and thePharisees was the latter's rejection ofstruggle and growing view that theKingdom could only come by themiraculous intervention of God." (33)concern manifested itself in the prophetsas a concern for the very concretemachinations of empires, armies, andpoliticians at the time.Evans sees two emerging elements in thistheology that prefigure the coming ofJesus of Nazareth.First, in books like Jonah and in theWisdom literature, one can see anemerging internationalism wherein thepursuit of the unity desired by God by aspecific community is tied up with the lifeof all. The internationalism inherent in thelife of the church finds its roots in thesemoments. The good life is only possibleon the basis of justice and equality, andthis equality will eventually extend to all.Second, Apocalyptic literature points tothe coming Kingdom of God as the returnof the law:3 0T H E H O U R

3 1T H E H O U RAnnouncing the coming Kingdom of Godin its fullness, rather than its religioussequestration, meant announcing thesuppression of all empires and dominions.The suppression and destruction of theoppressing empires happens in, through,and with the coming dominion of the Sonof Man: “I saw in the night visions, and,behold, one like the Son of man camewith the clouds of heaven, and came tothe Ancient of days, and they brought himnear before him.”And there was given him dominion, andglory, and a kingdom, that all people,nations, and languages, should serve him:his dominion is an everlasting dominion,which shall not pass away, and hiskingdom that which shall not bedestroyed. (Daniel 7.13-14) Kingdoms arefalling in the coming of the Kingdom of allpeoples, all nations, and all languages.The one who is going to do this is aspecific person.Jesus of Nazareth takes up the propheticwork of preaching the Kingdom of God.Evans' exploration of Jesus' place in thecoming of the Kingdom can at times seemtheologically thin. It would be a mistake,though, to assume he is not taking Jesusor the dogmatic tradition seriously. Evansdoes not dwell at length on these issuessimply because he assumes them as willbe clear when his theology of worship is considered. He emphasizes in The SocialHope the practical work Jesus undertakesto preach the Kingdom as well as to beginthe process of concretely bringing it about.The model for his work are previousreligious figures like Moses and theprophets who help form the communityinto the unity that God desires. Jesus“discussed the method of its achievement;he came to inaugurate it.” (37)As Evans describes the actual work ofJesus on earth, he makes a point withramifications for his own theory ofChristian practice. Jesus worked to fulfillthe purpose and desire of the law,”'itsaspirations,” even as he changed themethods for pursuing the Kingdom. Jesusremains committed to the fundamentals ofthe Kingdom, he accepts entirely itsstrategy, but he acts tactically withfreedom from previous pursuits of theKingdom. The break becomes clear, forEvans, when we see the way Jesus doesnot simply accept the authority of inheritedtraditions. He sees himself as competentto judge their applicability to the Kingdomin terms of their practical value. Thesociety that would follow from JesusChrist would, like him, take practice ratherthan profession as its standard.What standard of practice did Jesuspropose for these judgments? “It was oneof the coming of an actual corporatesociety upon earth in which all men shouldbe adjudged of equal value, in which there

3 2T H E H O U Rshould be no exploitation or oppression,but complete justice between man andman.” (37) As from the very beginning,God's desire is for complete justicethrough equality between all people. TheKingdom was and is the place where thisjustice through equality comes to dwelleven if only in a fleeting way. Jesusundertakes to effect the Kingdom in sucha way that it actually transforms those heis in contact with at this time. Evansdescribes how the initial temptation ofJesus is a temptation to accept shortcutsto the Kingdom.Evans divides Jesus' mission into twoparts. The first part of the mission is thecalling and sending of the Twelve –preaching, healing, and confessing thatJesus is the Christ. This organizing workbegan to show people that there was away of unity and equality in the law; andsuch cooperation let them live at leastbriefly under this law. Jesus wasbeginning to create a new society wherejustice, liberation, health, and life werepossible. He was healing, feeding, andsetting people free to be together. Thiscampaign was leading to the momentwhen Peter would confess him as theChrist acknowledging what was tacit untilnow. As the prophets knew, the Kingdomwould arrive as the assertion of God'stotal sovereignty on the earth. Jesus wasand is the way of God's sovereignty overthe earth: here is the Son of Man who isGod ruling. Evans sees Jesus as God's act, defining what it is to be with God inthis world. Jesus sets up the Kingdom,something we cannot do, but does so insuch a way that we can become fellow-workers in that Kingdom. Divinesovereignty is whatever way Jesus acts.Evans is not, therefore, taking away fromGod's activity when he describes Jesus'teaching:"In germ, he taught, the Kingdom hadactually come, it was among men, butin its fullness its coming dependedupon its acceptance by men. It was aKingdom of righteousness and peaceand active unwearied forgiveness.The gospel meant a new communitywith new standards and the equality itproduced included a full equalitybetween men and women." (46)The second part of Jesus' campaign is themove to Jerusalem and his assault on theauthorities there, “where he deliberatelyran his head into the noose that was tokill.” (44) The cleansing of the temple is akey moment in Evans' account of Jesus'mission. The move against the templewas not a solitary act by Jesus but onewhere he led a mob to overturn the tables.“It was a violent act: it was a usurpation ofproperly constituted authority, and for it hegave his reason, a reason which historymust judge to be adequate: ‘My Father'sHouse is a house of prayer, but ye havemade it a den of thieves."' (45-46) Evansviews Jesus as violent here because the

turning over of the tables is aproclamation of divine sovereignty andpower against another power. To declareJesus and a mob in power will lookrevolutionary to those currently in power.Evans continues to exegete Jesus' trial sothat the people did not abandon Jesus.The trial takes place at night in secretwhen the crowds and pilgrims weredistant from Jesus. It is the Chief Priestsand the Sanhedrin who shout forBarabbas. Once he is condemned thepeople do not simply abandon him. “Andthere followed him a great company ofpeople, and of women, which alsobewailed and lamented him.” (Luke 23.27)Later, as Jesus dies upon the cross, “allthe people that came together to thatsight, beholding the things which weredone, smote their breasts, and returned.”(Luke 23.48) The people, the crowd, themob, do not abandon Jesus at the cross.The struggle ending in the cross was notwith the people but with the authorities.His solidarity with the poor could not bebrought to an end.The crucifixion is the overcoming of theauthorities through the practice ofsacrifice: “the only sure and final way tooverthrow an evil domination was to placeover against it a community boundtogether by love and prepared tosacrifice.” (49) The domination was to bedefeated through unwearied forgivenessand sacrificial love. The resurrection was“the sign of the triumph of his Kingdom.”(55) It is possible at this point to take up thiskind of sacrificial love, with accompanyingdramatics, as a call to what is effectivelypolitical quietism. Evans takes this inanother direction entirely. He endorsesneither a quietism, nor a busy activism.He knows that Christians cannot simplybring the Kingdom, “And he said untothem, It is not for you to know the times orthe seasons, which the Father hath put inhis own power.” (Acts 1.7) They are not,however, meant to be idle: “But ye shallreceive power, after that the Holy Ghost iscome upon you: and ye shall be witnessesunto me both in Jerusalem, and in allJudaea, and in Samaria, and unto theuttermost part of the earth.” (Acts 1.8) Thefollowers of Christ do not know when theKingdom will be restored in fullness,nevertheless, they possess the powerappropriate to their task. When they goout to Judaea, Samaria, and the ends ofthe earth, they will go out with powerfulgood news. “Not good news whichbypassed their real problems. This it didbecause it proclaimed the advent of a realkingdom of justice and denounced thefalse kingdom in which they eked out aninferior existence.” (54)3 3T H E H O U R

3 4T H E H O U RFollowing the Ascension, we are facedwith the question of how to be dulycommissioned fellow-workers in theKingdom inaugurated by Jesus Christ. Weare set free from the strictures of the worldto live from the love given to us in JesusChrist. The basic structure of propheticaction reappears in the church who nowcall all people to the unity made known inthe Kingdom of God by Jesus Christfreeing them from worldly respectability.The dynamic of struggle in Christ's life, hispowerful embodiment of the laws of theKingdom against its enemies, leading tohis sacrifice upon the Cross, reappears inthe life of the church.The complexity of the Church’s currentsituation is the result of two factors: graceand internationalism. Evans turns to St.Paul, “both the leading strategist and theleading tactician of the infant ChristianChurch,” to show how these two factorscan be negotiated as part of thepreparation for and fellow-working in theKingdom of God by the Church.Paul does not offer a new interpretation ofthe law or additional laws. Paul's teaching“was a belief in the outpouring of the Spiritof God upon his servants, the result ofwhich was that whatever they did wasright. They were no longer under law butgrace.” (68) The doctrine was clearlydangerous and remains a source ofdanger today. The temptation will be to see the movement of the Holy Spirit asfreedom from engagement with the worldaround us. The error is temporal andmoral. The error is temporal in failing torecognize the nature of the present time oftransition into the Kingdom: “Then comeththe end, when he shall have delivered upthe kingdom to God, even the Father;when he shall have put down all rule andall authority and power.” (I Corinthians15.24) The current time is the prolongedperiod of Christ's destruction of all rule,authority, and power. The quietist positionassumes the irrelevance of the historicalprocess. It rejects the sense of creation asthe theater of God's activity. The Christianposition, however, sees the present timeas the continuation of the struggle againstrule, authority, and power in cooperationwith Christ's power and his Spirit.“[Revelation 21.1-22.5] was a majesticvision, but it was a realistic vision; onewhich faced the cost involved in the factthat there is no triumph of good save withthe collapse and overthrow of evil.” (79)The struggle continues in a mannerappropriate to its location in the process ofsalvation. The Church cannot substituteany law-giving authority in the place ofJesus Christ. No bishop, no president, nojudge, no court, and no police officer cantake his place. The analogy for thepresent time is the desert years underMoses: here the future law is forged in thewrestle of worship with God so that thesaints will be ready to take command ofthe situation at the right time.

Paul's victory in the early Church was tosecure its internationalist commitments.The unity of the body was to be potentiallyunlimited. Paul saw the need for thisbecause he saw the coming of theKingdom not as a limited rescue operationbut an attack on “a world-order based onhatred.” (70) The unity was not to besecured by either a homogenous identityin the Church or an abstract unitydetached from concrete life. The tendencyto see Paul as a reactionary or aconservative figure fails to appreciate theway Paul pursued the goal of aninternationalist Church. Evans describesthis failure as a failure to distinguishbetween strategy and tactics. Thefundamental strategic commitment to theunity of all people in, through, and withJesus of Nazareth cannot be questioned,but everything else could be negotiated:The strategy of the Kingdom of God hadto be pursued without wavering whiletactically Christians were to go as far aspossible without endangering the growthof the community. A number of seeminglyfaithful and conservative readings of Paulthat attempt to continue to implement hisspecific guidance to early congregationsin fact straightforwardly betray his intended purpose. So, Evans maintains,Paul could tactically call for submission tothe oppressing State given the generalsituation while remaining fundamentallycommitted to the fact that the same Statewas passing away. The strategic fact wasthat Christ was going to abolish 'all ruleand all authority and power' even iftactically the Saints needed to pay taxes.Evans sums up Paul's approach: “[St.Paul] saw there could be no fundamentalchange, no ‘Kingdom of God,’ until theRoman Empire had doomed itself by itsown rottenness, but also only then if the"Saints" were strong enough to takecommand of the situation.” (72)How, if we remain in basically this sameposition, can we continue in this fellow-work of the Kingdom?To continue this project, two things arenecessary: worship and criticism.Worship, which for Evans is primarily theeucharist, is necessary to the Christian lifebecause in it we are united to Godthrough Christ and to each other. Worshiptakes place in a specific place with theunderstanding that those specific "We have to shock people on fundamentals. We are notbound by any details—we are under grace—but let us notshock people and divide our own ranks on things whichare not fundamental. Let us not use our liberty as acloak for maliciousness. Where things do not matter wecan conform in order to press the deeper argument. " (72)3 5T H E H O U R

3 6T H E H O U Rcircumstances are capable of showingforth our fundamental unity materially andspiritually. The whole of life comes to ourworship, the offering of self andpossessions in the offertory, to find itsunity in the united act of the altar."The sacraments enact and proclaimwhat Christian doctrine asserts, thatgood is not an abstraction butsomething which has to be madeincarnate, that truth and peace andjustice and all that is desirable are notphrases to be mouthed but realities toassert and realities which have to beworked out in the entire order ofhuman society and expressed inmaterial terms." (256)The eucharist shows the unity of humanbeings with each other in concrete,material, and worked-out realities ratherthan in some abstract form. The worshipof this group shows the possible unity justas the unity of the desert showed whatwas possible for the Israelites.More than merely illustrating unity,worship of God transforms worshippers. Inworship, we experience “God whose verybeing gives all human beings that serenitywhich is one of the deepest needs of theirnature; the experience of Jesus ofNazareth, his life and teaching andsuffering and resurrection” leading us tothe exultant inspiration of the Spirit. (246)By beginning to live Jesus' life in our prayer and in our worship together, we arebecoming like God. The experience ofworship is at some level the experience ofthe Triune God as we slowly becomeincorporated into that God. At every levelthis participation engenders sharing inthose who worship Jesus of Nazarethbecause to worship him, to follow him, isto accept his teachings. We are set free tofollow his way of life because we, like him,are in total dependence upon God theFather for the nature of our identity. Ourunity, our sharing, our suffering, and ourlove of others does not secure this identitygiven through Christ, but expresses it.“The tragedy of life is division: the goal oflife is unity. The sacraments assert theunity of spiritual and material, for life iswhole; they assert the unity of aspirationand fulfilment; they assert the unity of manwith man; they assert the unity of manwith God.” (256) Worship places us in theSpirit, and it is in the Spirit's power that weare able to live free from the falseconstraints of this world.Worship is necessary for the life of thechurch because it enacts the actualdominion of God in this time and place. Init, we live in the future where Christ has“put down all rule and all authority andpower.” For a time we taste the reality ofthe Kingdom.The unity of the Holy Trinity in the life ofthe Church, and the unity of all people – aconstant and perpetual Pentecost, leads

3 7T H E H O U Rus to the necessary work of criticism.The work of criticism includes theologicalcriticism of different forms of belief. Wetend to become like what we worship so it“follows that there is no more importantquestion than what Christians havethought that God is like.” (245) Theexemplary instance of this criticism is theorthodox attack on Arianism. Arius affirmsthe Son as the first of creatures so Jesusis not, therefore, able to reveal the Fatherand is capable of change. Evans sees theArian position as a denial of fellowshipbetween Son and Father as well as adenial of the consequent fellowshipbetween God and humanity. Arians would,then, have been on their way to denyingthe fellowship of the Church and theKingdom. The Arian denies ourknowledge of God by denying ourfellowship with God and with each other.Against this position, the orthodox faithturns to a Son who is of one essence withthe Father, capable of revelation,dominion, and fellowship for all time. WithGod and humanity united in Jesus ofNazareth, we know that humanity can bemade like God in its worship and lifethrough its fellowship with God in Christ.The deifying community established in thedivine-human fellowship “is the perfectionof community in which individuality is notblotted out, or unity, as a consequence,impeded.” (248) Orthodox teachingdemands an egalitarian society whereinindividuals are freed from the terror ofcompetition. The attack on the egalitarian fact of the Kingdom will come as a revivalof past heresies of Arianism andsubordinationism and so our theology willneed to be held in constant criticism inlight of the truth revealed in Jesus Christ.Orthodox doctrine stands behind thesocial hope of the Christian Church. Partof our task is to work to proclaim in wordand deed that faith in its fullness byjudging our ideas in light of the fact of theincarnate God. The doctrine of the HolyTrinity and our fellowship with that Godprovide adequate criteria for makingcritical judgments about what we believeand how we live. Our doctrine cannot beseparated from our life together:The orthodox confession demands thesocial life of the Kingdom. Those who arenot interested in one will not, in the end,be interested in the other.Criticism must have its way with our ownmoral lives as well. Justice and moralitymust “be applied fearlessly to all sociallife.” (237) Again and again Christians

3 8T H E H O U Rhave been tempted to find some aspect ofhuman life to exempt from the moralquestioning Jesus requires of us. Suchexemption allows, in subtle and in obviousways, for the sin of Lenin, Stalin, andTrotsky to recur in the life of the Church.Evans sees a close parallel between Marxand the New Testament when each pointout the way morality is related to thesocial class of those attempting to bemoral, “How hardly shall they that haveriches enter into the kingdom of God!”(Mark 10.23) The counter to this socially-determined morality is a universal moralityappropriate to the future unity of allpeople. The Christian and the Leninistpart company at this point. The Christiancannot say that the peaceful ends justifythe violence of means necessary tosuppress the opposing classes. Thereason is not so much pacifism, whichEvans does not endorse, as the Christianinsistence on an objective morality notentirely determined by social class, whichputs the Christian rather than Leninistcloser to Marx for Evans. There is somepower that breaks through these classconceptions to point a way forwardwithout them. The moral criticism falls justas harshly on the respectable gentleman.The person who aims for the life ofrespectability by following the moral codeat hand, without asking after it, exemptstheir life from moral trial as surely as therevolutionary who murders withouthesitation. Evans quotes Gore's stingingcondemnation of the well-to-do Englishman, “Conscientious within theregion of the traditional and expected,they are almost impenetrable to light frombeyond.” (238) They may move throughsociety as respectable planters, judges,priests, bishops, presidents, teachers,soldiers, and students capable of makingsacrifices to fulfill their moral obligations.They will fail as fellow-workers in theKingdom because they cannot see theneed for moral progress and criticism.What is the basis of this moral criticism?How do we know our morality isprogressing towards the morality of theKingdom?The criteria of our morality is the samecriteria as the Kingdom: the sharing of ourlife and the sharing of our goods. Thesharing is the result of our love becomingmanifest in our spiritual and material lives.The teaching of the prophets, of Jesus,and of the Bible:"...is that love has to be expressed inmaterial terms as well as spiritual andwhen this happens it needs noexplaining away. As to calculationsabout the end of the age, the entiremission of the Church was (and is) tobe ready for the end of the age andreplace it with something orderedaccording to the will of God." (62)The real sharing of our lives, our realfellowship, is what we are forging,

practicing, struggling, and sacrificing foras we prepare for the Promised Landwhere Christ has “put down all rule and allauthority and power.” We prepareourselves through this integrated life oflove, sharing, peace, and righteousness tooverthrow the evil of our division:"The only kind of economic systemwhich is compatible with and isexpressive of, the Christian way of life,is some form of sharing of the materialgoods of the earth and it would seemto be a primary Christian duty to playa part in bringing such a system intobeing. This is a Christian viewbecause it is in fellowship which isexpressed in sharing and arises out ofsharing that the Christian seesheaven: fellowship is heaven, and lackof fellowship is hell." (232)To say all of this, for Evans, is not to takea “social” or a “political” view of theGospel. “It is a statement of the simplefact that there is no such thing as aChristianity which is not an assertion inthe midst of the present world order of thelife of the resurrection and which is not,therefore, in the deepest of all possiblesenses, a revolutionary agent in theworld.” (249)Will we be that agent? Will we read theBible? Will we follow this Jesus ofNazareth? Will we worship the HolyTrinity? Will we share of ourselves?Will LevanwayChattanooga, TN3 9T H E H O U R

If we are not lying, we are saying thingswe believe are true. Or at the very least,what we wish were true. And when weintentionally refrain from saying things, wetell on ourselves.Recently, Rabbi Andy Kahn(@rabbiandykahn) said on Twitter: “Is it just me, or is the term ‘person ofJewish faith’ grating?... I don't knowmany actual Jews who identify as‘people of Jewish faith.’ It reducesJudaism to a belief system, whenthat's only one face of the multifacetedjewel.”I can’t speak for the rabbi, but I also don’tcall myself a “person of faith,” and for thesame reasons; because “person of faith” tends to function for progressiveChristians in the same way “judeo-christian” functions for culture-warconservatives: it gestures to a supposedpan-religious consensus about this or thatissue and, more broadly, it describes aubiquitous mode of existence: the“religious.” Religions, such languageassumes, may have some specifichistorical or cultural forms, but they allspring from a universal human need andaddress a universal human practice.“Person of faith” and “faith communities”work as democratizing speech. Incommon use, it is a way of politelyrefusing to suggest one religion is “better”than another. It has the side effect ofsuggesting none are at root different thananother.4 0T H E H O U R"One can no more be religious in general, than one can speak language in general"George Lindbeck, The Nature of Doctrine