Return to flip book view

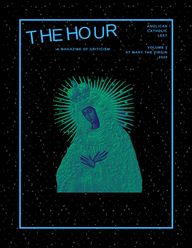

ETHHOURA M A G A Z I N E O F C R I T I C I S MA N G L I C A NC A T H O L I CL E F TV O L U M E 1S T M A R Y T H E V I R G I N2 0 2 0

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T ST O T H E S O U R C E S : A S T U D Y I N A N G L I C A N S O C I A L I S MT O N Y H U N TR E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NA N D R E W M C G O W A NT O A L L B I S H O P SA R I M O N T SW I T H O U T E X C U S E : T H E C R I T I Q U E O F N A T U R E A N D C H R I S T I A N S O L I D A R I T Y W I T H B L A C K L I V E S M A T T E RC A L E B R O B E R T SS P E C I F I C I T Y A N D M O R A L I M A G I N A T I O NH A N N A H B O W M A NF O U R P O E M SA N N E - M A R I E W A R N E RV I D A S C U D D E R : A C O M P A N I O N F O R T O D A Y ' S C O M R A D E SJ O N A T H A N M C G R E G O RS O C I A L I S M A N D S P I R I T U A L P R O G R E S S : A S P E C U L A T I O NV I D A D U T T O N S C U D D E RA N N O T A T E D B I B L I O G R A P H YT O N Y H U N T020821253039364266

One of the downsides of an MDiv programallowing a surfeit of electives is that itindicates a school doesn’t have a clearidea of what kind of intellectual andspiritual formation it desires to produce.But the upside is that I have been able toorganize some independent studies formyself on topics of my own choosing. Thislast semester I managed to find aninstructor who was willing to supervise mefor a study in Anglican socialism. So Iwent about constructing a schedule ofreading.I’ll never forget something the Pentecostalscholar Gordon Fee once wrote abouthow he approached commentary writing.He spent all of his time in the first monthsfocused exclusively on primary sources,even cautioning that the BDAG (thepreeminent New Testament Greeklexicon) is a secondary source. Whenyou’re familiar with primary sources you’llbe better able to engage critically with thesecondary ones. This is the approach Ihave taken to my own studies ever sinceand it guided how I structured this class.It was to be a reading-intensive class.Rather than produce a paper, I wouldcreate an annotated bibliography on whichI could draw for future study. Additionally itwould give me the bones necessary toconstruct a syllabus for teaching. Later Icould fill in the historical gaps with theliterature, better prepared to contest theirreadings where necessary - historians sooften being plagued by a tin ear fortheology.Little by little I amassed a gigantic readinglist. I was going to devour every work byevery major actor in the genre from F. D.Maurice to Kenneth Leech. And little bylittle my supervisor, friends, and enemiessuggested I whittle down the list tosomething more manageable. With deepregret I complied, and decided to cutbishop Westcott, reformist socialists, andanything after William Temple. This wasjust before a global pandemic shut downmy access to the school library. Withalmost no warning we were forbidden toenter, and several of the books I hadintended to read sat untouched in my 0 2

before anyway. But I saw their protest in anew light. The Tracts are not anti-institutional in any way. Several lamentthe loss of prestige and favor the Churchof England had suffered in recent years.The key, as I see it, lies in their polemicalfuror over the encroaching reach of anincreasingly non-Anglican state. Whyshould a non-believer, or worse - apresbyterian - have any say in howdioceses are organized? The church’sauthority is not derived from the politicalrealm but directly from the apostles, theysaid. So while disestablishment wouldhave been viewed as a catastrophe, theiradamance about the priority andindependence of episcopal authority setthe Church of England against thegovernment of England. This is a tacticthat would be used by those who cameafter.I chose not to do much with the slumritualists. In my defense few wrote anysignificant works, and not many werequite the social advocates we rememberthem to be. Most of the ritualists were notin east London but in middle classsuburbs, and those who were, while theydid of course do social work inneighborhoods long neglected by the C ofE, were not particularly radical in politics.For my study their significance lies in thefact that they continued the anglo-catholicpenchant for protest; only in this case theyprotested their own bishops. In the ritualist 0 3A D F O N T E ST H E H O U Rcarrel. My personal chapel of knowledgebeing consigned to dust collection for theforeseeable future, I applied myself tosuch works as I could gather over theinternet. Unfortunately late-VictorianAnglican socialism is not a lively field ofstudy and I was forced to supplement mydigital archive with some works I had onhand at home. So a dash of Charles Gorewas back on the menu, and I added anessay by Gerrard Winstanley to the mix aswell (and how fortunate that I did!).For the most part all I really wanted wasan eagle’s eye view of the field, but therewas one little question that kept naggingat me: Why was it that, when it camespecifically to Christian socialism, themajority of players were anglo-catholics?Does it not suggest some kind ofconnection? Broadly speaking Anglicanswere not labor leaders. Secularists,methodists, and other non-conformistsplayed a role in organizing as well. Butmine wasn’t a study, strictly speaking, inEnglish socialism. If it were I would’veincluded William Morris, the architect ofarts and crafts communism. I had toconstrict myself to narrower concerns. Inorder to answer this question I began theclass with a study on relevant Tracts forthe Times, hoping to discover somethingwithin their digital pages (It is outrageousthere is not a proper edition of the Tractsin print). The Tracts did not surprise mewith anything. I had read most of them

side of the atheists, which only furtherdiscredited them in the eyes of theirecclesiastical leaders. Stewart Headlam,for example, was denied a license by aseries of London bishops and was neverable to hold down a parish position for hisassociation with the irreligious and withballerinas.Figures like Headlam, Percy Dearmer,and Conrad Noel often wrote apologies toboth sides. To the secularists they said,Christianity is with you; the catholic faith,properly understood, demands christiansbecome socialists. This was a positionthey had to make to their own church aswell. If you’re a christian, they said, youneeded to be a socialist. Jesus, theapostles, and church history confirmed it.They inherited this conviction from F. D.Maurice, a controversial figure from earlierin the 19th century. Maurice’s Kingdom ofChrist attempted to synthesize theprimitive insights, as he saw them, of allthe major protestant schools into a visionof a universal, spiritual kingdom. TheLutherans, the Calvinists; even Zwingli,the Quakers, and Unitarians were all“really” on the same page, but bad religionhad crept in to dull the power of their initialrevelations. Maurice argued in the bookthat bishops, liturgy, and the sacramentswere necessary elements of this kingdom,but did not equate this “catholicism” withthe Roman catholic church. In the early 0 4A D F O N T E ST H E H O U Rcontroversy we see anglo-catholicismexpand its willingness to question not onlyits political, but its ecclesial authority -Ironic though it may be! To be anglo-catholic came to be seen as beingunmanly, and unenglish. The anglo-catholic socialists, then, were quite usedto being a beleaguered minority voice intheir society and even in their own church.Without this antagonistic identity, it seemsto me we cannot make full sense of theconnection between their politics and theirreligion.Not that all anglo-catholics were socialists.Indeed few were. The Church of Englandwas willing to talk a big game at times for“social reforms,” but by and large theestablishment was quite happy to keepthe establishment afloat. It moralized thepoor and drew distinctions between“deserving” and “undeserving” membersof the lower class. It judged working classentertainment. It weaponized thecatechism against labor "overreach,"believing everyone in society had a“place.” One should not fight against one’sbetters. Social hierarchy is God-ordained,thus it is nearly sinful to battle against it.Secularists exploited this to great effect.The state’s religion clearly wanted to keeppeople oppressed. Anyone who allied withthe Anglicans allied with drawing roombishops and capitalists. Anglican socialiststherefore often found themselves on the

Maurice, and the relationship of oursocialists to the secularists and to thestate church. I make no claims tocomprehension. It was with regret that Ididn’t even make it to William Temple, letalone the mid-century resistance to SouthAfrican apartheid and the emergence inBrittain of the Jubilee Group. The pre-19thC English radical tradition isabsolutely worth exploring more. Thehistory of Wat Tyler and John Ball couldbe added to political tracts by Tyndale, theLevelers, and Winstanley. I am keenlyaware of the fact that Vida Scudder is theonly woman to appear on the list. It’s notbecause women weren’t important inAnglican socialist work, only that I focusedthis course on what we might call“theorists.” A broader study would need toinclude more of those who labored on thelines.Scudder is more often taught in Americanhistory courses than in seminaries, whichis a shame because her socialist writing isperceptive and lovely. Another American,the eccentric Frederic Hastings Smyth,manages to lucidly and creativelysynthesize marxism and thomism inunexpected ways. His great Manhood IntoGod is rather difficult to find, and the bookis long enough and late enough that Ididn’t have time to read it for this class.Over the summer I’ve spent more timewith it and absolutely consider it worthreading. I managed to digitize a shorter 0 5A D F O N T E ST H E H O U Ryears of the Oxford Movement Mauricewas a supporter. Eventually he came tohate their dogmatism, and the way somereveled in damnation andotherworldliness. Several of the anglo-catholic socialists got their understandingof catholicism as much from Maurice asfrom the Tractarians.Maurice was a high-Tory paternalistwhose christian socialism was just finewith inherited position and socialhierarchy. He was influenced particularlyby utopian socialists and prized “co-operation” over “competition.” I saw thisframing run right through most of thepeople I read. As marxist socialismbecame more influential in England, somemaurician disciples quietly adopted moreradical politics but never repudiated theirmaster. What socialism meant was hotlycontested and fluid at the time, and ourfigures often alternated from preachingco-operatives, to a georgian land tax, toindustry nationalisation.I’m trying to avoid giving a mere historylesson. There are several books andessays that make for more completereading than what I can offer here, and Iwill list some of them below. But I feel likewhat I’ve said helpfully contextualizes thebibliography I will be sharing. I’vementioned the Oxford Movementconnection, the ritualist antagonismtoward the bishops, the influence of

end she found him moralistic, anti-democratic, and inimical to socialism. Tobe fair, he’d probably say the same! Butas recent work by Eugene McCarraherindicates, Ruskin can still be drawn onfruitfully for socialist thinking. I was oftensurprised in my reading, and encouraged.The Anglican socialists were violently anti-imperialist, and enthusiastically embracedthe belief that capitalism and imperialismwere fundamentally linked. Though theyfailed to make the connection ofcapitalism with slavery and race. Butmany called for disestablishment of the Cof E, firmly believing that its official statusonly prevented it from taking the Gospelof liberation seriously.Going in I had expected to encounter agreat deal of naive nostalgia for theMiddle Ages, but I’m convinced they areread wrongly in that respect. Figgis andTawney broke important historical groundon the political and economic shifts of thelate middle ages, and even someone asuntrained as Noel looks to the period lessas something to uncritically reinstate andmore as precedent that Christianity andcapitalism are not ontologically linked, asmany of his peers in the Anglican churchsupposed. Noel preached carnival andpicket lines, not masculinity and Latinmasses.I didn’t create my study because I thinkAnglican socialism is the best socialism, 0 6A D F O N T E ST H E H O U Rbook of his before the library shut down,but it would be nice to have even a pdf ofManhood Into God. Frances Perkins,labor secretary for FDR, was at least for ashort while a socialist, and belongs to thisAmerican story as well. If I were doing theclass over again I’d probably leave outNoel’s Life of Christ entirely and addsomething by the guild socialist JohnNeville Figgis. I’d give more attention toHenry George and T.H. Green for theirinfluence. There would need to be asection on Marx’s reception, which wasmore sympathetic in America than inEngland for the most part. Ruskin iscentral to the figures of the time in a way Ididn’t realize and I should’ve spent sometime in the letters of Fors Clavigera.Not unlike the way Maurice was modifiedstrongly by his disciples without coming infor explicit critique, I noticed Ruskinpeeping in from beneath the covers of,say, R. H. Tawney’s The AcquisitiveSociety. Yet without ever saying so,Tawney corrects him. Where Ruskinchampioned the captains of industry,social hierarchy, paternalism, inheritedwealth & property, Tawney argues fortheir elimination, advocating for socialequality, and self-rule for industry in acoalition of manager and laborer, withstringent limits on investment returns andbrutal taxes on inheritance. Scudder toowas a disciple of Ruskin, even producingan entire book on his thought. But in the

Without claiming to have now become anexpert, I close with a list of suggestionsfor people wanting to make an initial forayinto the primary sources.TONY HUNTMinneapolis, Minnesota0 7A D F O N T E ST H E H O U Ror more important than the wider labormovement, or any of that. Butressourcement is one of the primarymotivating factors behind this magazine.There isn’t any one position among themwe have blindly to adopt. The point isn’t tosimply regurgitate the beliefs of ourprogenitors indiscriminately. It’s to situateourselves inside of an historical body towhich we are accountable, and a traditionfrom which we can draw. We make noclaims to be The Representatives of TheTradition. Christian socialism goes backmuch further than modern socialism andstill has something to say to our currentsituation.If you were looking for an essay-lengthintroduction to our topic, I happen to knowthat the Anglican Theological Review isgoing to publish an essay by Gary Dorrienon it in the Fall 2020 issue. I’ve read it andit’s typically energetic and informative. It istoo bad the Americans aren’t representedbut I suppose he’ll rectify that as soon asthe next volume of his history of socialdemocracy comes out.Peter d’A. Jones’ The Christian SocialistRevival: 1877-1914 is an excellent booklength treatment. It’s incredibly well-organized and I think the way he framesthe middle section around the Guild of St.Matthew, the Christian Social Union, andthe Church Socialist League is fantastic.

Renewing the Anglican CatholicSocial TraditionA N H O U R S P E C I A LANDREW MCGOWANDEAN & PRESIDENT of BERKELEY DIVINITY SCHOOLFRAGMENTS OF A MANIFESTOBased on an address to the Society of Catholic Priests, Tucson, AZ, October 4th 2019

we need to find both old ways and new toanswer God’s call for a just, participatory,and sustainable society.CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM, NOT SOCIALGOSPELWhile it is important to work with othercitizens of all faiths and none and to findcommon cause where we can, based onhow the Gospel tells us to view ourhumanity and theirs, it is important todistinguish between how we buildalliances and how we form our ownidentity and social witness. It is a time tore-discover what Christians, and herespecifically Christians of catholiccommitment and formation, bring to thereality of a society groaning under theburdens of our time.Baptism is of course as fundamental to usas shared humanity itself; it is moreimportant than shared opinion. We aremore inextricably bound to baptizedTrumpians than we are to the unbaptized,even those whom we like and agree with.Yet we are also more different from someother Christians than we seem to realize.We need to work this out, not so as toseparate ourselves, but so as to beeffective allies in the broad coalitionsneeded for the present moment.For this purpose, I want to distinguishChristian Socialism from the “Social 0 9R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U RTHE PATHOS OF THE CHRISTIANSOCIAL ORDERTo say that we live in challenging times ismerely to state the obvious. They arechallenging for the Church, assecularization takes form more quickly inNorth America than most of us can grasp,but more challenging still for populationshere and globally that are dealing with theeffects of late capitalism out of control, viaclimate change in the environment on theone hand, and gross income and wealthdisparity even within the wealthiestsocieties.While numerous Church groups areoutspoken on a variety of these issues,few of these seem to be wholly aware thattheir political practice is based onpremises that no longer hold; despite themuch vaunted separation of Church andstate in the US constitution, ecclesialstatements about policy and social issueshere often have the ring of Christendomabout them. This is a challenge for all of us, includingthose of us in the Catholic tradition ofAnglicanism who inherit a rich socialtradition, yet one based partly (not wholly)on assumptions that no longer hold, aboutthe idea of a “Christian” society or socialorder. We do not yet know how to beChristians in a post-Christian society; wecling to influence that has already gone;

Gospel,” not to divide us further, but toengage critically on what unites us, and tomake a claim about how Christian beliefand social action might be linked fromwithin the Catholic tradition.While people sometimes use the term“Social Gospel” fuzzily to refer to anyengagement between Christianity andsocial action or policy, its historically-formed meaning involves deep connectionwith 19th and early 20th centuryliberalism. The “Social Gospel” morestrictly is the movement associated withWalter Rauschenbusch, whose theology,like that of many of those good folk since,includes a modernizing rejection or de-emphasis of aspects of traditional doctrinesuch as personal sin or the need foratonement. Whether the idea of a “SocialGospel” is useful really stands or falls onwhether the meaning of that term impliesa missing part of the Gospel, or (as moreoften) a re-working of the Gospel, toproduce a salvation primarily focused onthe arrival of the Kingdom of God on earthvia a utopian society. In this latter andprevailing sense, I contend the SocialGospel is not either as Christian, or (moreshockingly) nearly as radical, as itimagines.Christian Socialism has a quite differentintellectual pedigree, even if it overlapswith that of the Social Gospel movementat some points. This is partly a continental difference, admittedly; the Christian SocialUnion in the UK, from which themovement takes its name, was led andinspired by people like F. D. Maurice, whowas himself not of the Catholic party inthe Church of England, but was soonjoined by such as Charles Gore and PercyDearmer who were more clearly so. ACatholic form of Christian Socialism wasthus a second-generation outgrowth of theOxford Movement, just as ritualism was.While not all Christian Socialists wereAnglo-Catholics this movement, incontrast with the Social Gospel, tended tobe orthodox in its assumptions, and to seethe lack of effective social witness andteaching as reflecting not so much afailure of traditional doctrine as a failure tounderstand and uphold traditionaldoctrine. There is the big difference, atleast theologically.If you balk at the use of “Socialism,” letme point out that many of the Anglicanswho have identified with ChristianSocialism were hesitant, or varied in theiropinions, about “state ownership” or otherspecific forms of socialist organization,and that this not what socialism meant ormeans. As the origins of ChristianSocialism in a “Christian Social Union”suggest, “socialism” simply means a viewof society that emphasizes for the needsof the whole. Socialism here need notrefer to nationalization of industry etc., butto a variety of policies and remedies 1 0R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

intended to share the benefits ofproduction equitably, to ensure fullemployment, minimum income, universalhealth care and education, and so forth.These are not outrageous ideas assumingauthoritarian rule, but parts of what wasmainstream policy under FDR, when itcomes to specifics. Socialists will differ inthe means they believe it necessary touse to further these aims, but socialismshould be understood not just as anidentity marker for self-proclaimedradicals, but as a way of thinking aboutthe need for a robust civil society in whichthe needs of all, and especially of themost vulnerable, are met.While both movements may support someof what I have called socialism, ChristianSocialism and the Social Gospel are notthe same thing. It makes all the differencein the world whether we think socialimprovement is somehow the realmessage of Christianity, or whether wethink that the Gospel, and the relation intowhich it brings us with the triune God inthe Church and through the sacraments,depicts and demands life lived accordingto the pattern of Christ and its fulfillment inall aspects of human life.This means, among other things, thatChristian Socialism is not a form ofliberalism, even if it makes common causewith liberalism at various points. Thedifference between Christian Socialism, which I take to be the natural and historicpartner of the Catholic movement in theChurch, and the Social Gospel movementis two-fold and both those parts have todo with liberalism and its weaknesses.“Liberalism” as a term is used in differentways in different English-speakingChristian traditions, admittedly; but here Imean the set of optimistic and progressiveforces that span both theological andpolitical movements in this country.One of the struggles facing an AmericanChristian Left, in broad terms, is that therewas no moment such as that whichEurope experienced in the Great War,when the accommodationist theologies ofRitschl and Harnack, the greatest mindsof German liberal theology, were enrolledto defend German imperialism. Out of thiscatastrophe came Barth, and an end tothe idea that a progressive Christianitycould function by taking its bearings fromsocial trends primarily from the widerworld.Of course should not expect AmericanChristian socialists to adopt Continental orBritish theological pedigrees in order tomake their theology or witness effective;to point to this difference of intellectualand historical pedigree is to warn of thepotential consequences of the missingequivalent a self-critical moment in theAmerican theological and social tradition.In fact American theology, like American 1 1R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

socialism, does its own traditions on whichto draw, but the place of liberalism and itsaccommodationist and optimistictendencies must be criticized in thatprocess. That process must also go onwith a critical awareness, that is hardlymuch in evidence now, that the place ofthe USA in the global reality of the 21stcentury is itself hegemonic andoppressive, and that no view of a justsociety can possibly take its bearings froma US-centered perspective alone, evenone that speaks from the point of view ofthe oppressed in this country. With thatstatement however I have moved to thenext part of my topic.DIVESTING FROM AMERICAI think all of us need to function asresponsible citizens of our countries, andto participate appropriately in theirinstitutions. I think however that it wouldbe timely for the Church - or let me saythe Christian Left, to which not all of younecessarily feel you belong - to reexamineits coziness with the American politicalproject. I am on eggshells here as aforeigner of course - and I do not mean tosuggest that my own or any other countryhas some sort of exemption from parallelor comparable challenges - but I do feelthat the curious and late arrival ofsecularism in the US has left manygasping and unprepared for a world inwhich the wider society does not care what we think.The Social Gospel is in fact inevitably,essentially, caught up in the Americanproject; hence its primary outlet is inseeking to pressure the legislative andexecutive branches to be better, always todo better. Such advocacy is not a badthing in itself, but it is a weakness not justin its unreflective optimism (and stultifyingmoralism), but insofar as it assumes thatthe relationship between Church andsociety ought to be cozy, and hence“protests” when it does not have its way.This may have been true of aspects ofChristian Socialism within the establishedChurch in the past too, by the way, but thedifferences are also significant.The Social Gospel movement will in facthave little left to say, if the Americanproject is taken away from it. Its optimisticand Pelagian aim is the American utopia,and while it has adjusted itself to themulti-faith aspect of that utopia, it has notreally let go of the assumption that USGovernment and society should be andcan be what the Social Gospel says theyshould be. This is why the Social Gospel’scurrent advocates experience suchdissonance at the Trump ascendancy.The problem lies in that the society ofwhich the USA is the hegemonic center isnot, at heart, just a utopia in the making,but a dystopia whose real character is 1 2R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

increasingly being revealed. Latecapitalism is not merely a system in needof tweaking, so that if we got (e.g.) gunviolence, or racism, and a few other thingssorted, all would be well. Late capitalismis essentially the rule of the bourgeoisie,or of capital itself, and while its ideologyalways pretends to offer equal opportunityit never will, let alone real equality inwhich it has no interest. Meritocracy is theveil it draws across a system that tends toinequality, and more and more so. Identitypolitics are merely a new version of thesame, drawing veneer of fake collectivismacross quests for personal fulfilment thatstymie real collective action more oftenthan they support it. Beauty contestpresidential elections are farces duringwhose performance the population is toldthat it has power that it does not, anddirects their energies towards these ratherthan to the roots of injustice, whoseorigins and solutions both lie elsewhere.This does not mean elections aremeaningless - but they do not mean whatpeople are told they mean.The Social Gospel movement oftendevolves into being a religious wing forone side of US politics, granted that isalso the side I would choose, if I werevoting. I know that Churches are usuallycareful about endorsing candidates atleast for tax exemption reasons, but this isa sort of sleight of hand. I am notconvinced that the Social Gospel movement has an understanding of itselfand of Christian faith that goes muchdeeper than the varied politics ofAmerican liberalism. Many of us arerightly appalled by the way someevangelicals like Robert Jeffords, FranklinGraham, and Jerry Falwell Jr havebecome sycophantic theologicalapologists for the crypto-fascism ofTrump. Yet when Barack Obama wasinaugurated in 2009, the then presidingbishop offered a prayer which was anexplicit mashup of Lincoln’s SecondInaugural address along with elements ofObama’s campaign rhetoric, and no-onebatted an eyelid. That is not so muchoutrageous as pathetic, in truth.You may object that there is a greatdifference between Obama and Trump,and there is. But inequality in this countrybounded ahead under Obama; detentionand deportation bounded ahead underObama. Obama was and is a person ofalmost infinitely greater appeal anddeeper character than Trump - but this isnot the point. The system over which theypreside is the same. Both men needprayer as presidents, but the exhortationof the First Letter to Timothy to pray forthose in authority can and must beunderstood at least in part as a version ofJesus’ command to love enemies, andpray for those who persecute you. Theadvantage of a Trump is that hiscorruption and venality are 1 3R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

transparent - he is the true face of latecapitalism. The Obama inaugurationprayer of course is actually a form of civilreligion, not of Christianity. One of themixed blessings of secularization is thatwe become freer to acknowledge this, butwe do so slowly.The same case also entails a dubious butrarely examined assumption, that theprimary role of the Church in socialchange is that of collective advocacy asChurch, as a lobby group in effect; and asa more pluralistic understanding of faithcommunities and traditions has appeared,or forced itself upon us, we simply movefrom being the religious conscience of theState to being the Episcopal branch ofprogressive civil religion. When our defaultmode of responding to issues of the day iseither to pass a resolution, or to put stoleson and go to the march, we are betrayinga latent dependence on our relationship tocivil religion. I do not mean to say weshould never do those things; perhapssometimes tactically speaking it is worthsqueezing the last drop of juice from thisold lemon. But an old and passing modeof witness it is.William Temple who as Archbishop ofCanterbury was an avowed socialist, saidin his influential Christianity and SocialOrder:Of course, this context was different; but itis striking how even in the establishedreality of the Church of England, Temple isconsidering not just the public witness ofthe Church as an institution, but the factthat the Church supports its members ascitizens in the political realm. All this isworth considering, from someone who wasalso vigorously championing the needs ofthe poorest in public. Does it really makeas much sense as people assume, to passsynodical resolutions as though this werethe clearest form of ecclesial engagementwith the issues of the day? And if it everdid, what now?I suggest that while we do need to witnesseffectively, both that the conventionalalliance that works via “public witness” is "At the end of this book I shall offer,in my capacity as a Christiancitizen, certain proposals for definiteaction which would, in my privatejudgement, conduce to a moreChristian ordering of society; but ifany member of the Convocation ofYork should be so ill-advised as totable a resolution that theseproposals be adopted as a politicalprogramme for the Church, I shouldin my capacity as Archbishop resistthat proposal with all my force, andshould probably, as President of theConvocation, rule it out of order." (London: SCM Press, 1950), 24–251 4R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

more damaging to Christian faith andidentity than is being recognized, and thatthe assumption about Church as collectiveagent in the American project is flawed inother ways too.The Church needs to remember, ordiscover, that being Church is actuallymuch more radical than being areligiously-inspired faction of theDemocratic Party. And surprisingly tomany, while local organization and otherforms of actual political praxis should playa role, an unflinchingly religious missionmay really be the most important thing theChurch can offers its members whosevocations and actions in the secular realmcan and must include political action.A GENUINE BAPTISMAL ECCLESIOLOGYIn recent decades “BaptismalEcclesiology” has become a sort ofweasel word, associated not so much witheither baptism or ecclesiology, but withthe polity of TEC. I assume, by the way,that while thinking about the polity of TECshould be informed by our ecclesiology,that it is not the same thing at all - yourtheory of your denominational structure isnot “ecclesiology.”Baptismal Ecclesiology has largely beenrelated to the proper recognition that thelaity have a fundamental place in TEC polity, as in any aspect of Church life.However, the associated problems of thisagenda are manifold, and some of themwell beyond the scope of this talk. In brief, Ithink we have often messed this up, alongwith the bold claim that the laity are an“order” of ministry, by imagining this isfundamentally to do with ecclesiasticalroles and concerns, rather than with theworld of which lay and clergy and Churchare all a part. I routinely hear “laity” nowused as a short hand for “lay leaders” or“lay volunteers,” rather than meaning “thebaptized” – so we have made this wholething very introspective, and have beenimplying that the depth of a lay person’svocation is typically to be correlated withtheir involvement in certain Churchactivities rather than in actions as citizensin workplace, home, and civic life. The“fourth order” part has also contributed tothis mess, because of its implication thatthe other “orders” provided the model onwhich the fourth would be understood,rather than the proper understanding thatthe clergy need to be understood relative tothe laos.But my real point here is that if baptismreally is the basis of ecclesiology - and it is- then your Vestry or parish program arenot its main grounding point or locus, andthe General Convention certainly is not.The world is its locus, and the ministry of allthe baptized takes place wherever theyare. A real baptismal ecclesiology would 1 5R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

entail understanding how the members ofthe Church - not the institution, but themembers - function as part of humansociety, and as participants in the widercreation.So what about in Church? I note one ofthe common misuses of the BaptismalEcclesiology language is its odd placerelative to the movement towards so-called “open communion.” For while theterms are often used by the same people,the movement to remove baptism as anecessary path to communion of courseundermines the “baptismal” part ofecclesiology rather radically.What this really involves, I suspect, is atleast in part a characteristically bourgeoisobjection to any structure or condition thatinhibits inherent privilege operating freely.The Church actually declares that baptismis radical inclusion, of the infant, the aged,the tentative, the fierce and faithful, allalike; it declares that God’s apparentlyarbitrary choice is more powerful thanyour spiritual biography. Those who aresupposedly excluded from communion bythe existing canon are not, of course,typically the marginalized or the poor, but(like many of the rest of us) the bourgeois.They - or rather they, as imagined by theirsponsors - are the educated nibblers atthe spirituality banquet, who feel a hungerfor on some given occasion without sittingdown in community - without the wedding garment, as Jesus puts it.This is important beyond that issue of opencommunion, because it goes to the heart ofwhat baptism is and what Church is.Baptism is the means by which the Churchdeclares Jesus' utopia as transcendingsocial location - it is not dependent onagreement or inclination, but on divine call.This is the only form of equality andinclusion that does more than hide privilegebut abolishes it; “open communion” on theother hand is the claim of the religiousbourgeoisie clamoring against traditionalpower structures that frustrate its veiledprivilege, when the Church is actuallycalled to work out how it can be with andfeed the materially poor. All this alsobreezes past the fact that baptism binds usirrevocably to others, regardless of opinionor confession, in catholic perspective atleast, instead of privileging opinion andexperience and other factors constructedby social location.THE EUCHARIST AND THE KINGDOMThis of course leads us to the Eucharist,which is at the heart of Christian socialwitness. One of the problems with someefforts at liturgical renewal at present is theassumption that liturgy is a sort of neutralvehicle, whose words need to be adaptedto make clear the propositions held in mindby the revisers. I don’t think we can orshould exclude revision, and I think it is 1 6R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

possible for the language of the liturgy (orforms of the liturgy) to evolve and come toreflect in more focused and contemporaryways the doctrines of the Church that arethe basis of political engagement - the factof Creation, Incarnation, Redemption.However in this audience I hope I don’thave to work too hard to say that suchefforts to solve liturgical conundrums bychanging the words are in danger ofmissing the real point.Every Eucharist is an act of subversion.This does not depend on how wellunderstood that fact is, nor on whether thewords used to frame the liturgy are thesharpest expression of that fact. For theEucharist does not work primarily bywords, even though words are essential toit. The Eucharist is a participation in theworship of the true God in the heavenlyrealm, as in the vision of Isaiah 6 or theRevelation to John. We are caught up intothat realm, but it is also the irruption intohuman life of the divine order. This is thecase, whether we do it well or badly; wecelebrate solemn high mass with awe,because we are explicitly indicating thatthis is like handling high explosives; thepower of the living God is not a trifle. Yetwe can also celebrate with warmth andquiet conviviality, because the divine orderis one of life and love and peace.What the Eucharist is not, is a neutralvehicle for the carriage of other agendas. The Eucharist is an agenda. Or rather itsagenda is the reign of God, the God ofJesus Christ. Its agenda is not that worshipis nice, or that ritual is meaningful, or thatthe transcendent is a thing, or that we arespiritual beings, or that community isvaluable; its agenda is that casting down ofthe mighty from their thrones and exaltationof the lowly, the filling of the hungry withgood things equally. In its symbolic mealand its equal proportions, given freely, itconveys the equal participation of all thosecalled to the heavenly banquet. Its equalityis a foretaste of the world in which all arefed.The Eucharist will be those things, eachtime we celebrate, whether we manage tocapture that fact in words or ritual, whetherwe manage to take its reality with us in ourembodied selves adequately or not. It justis. That fact, not a different ritual, is theessence of a catholic doctrine of theEucharist - that it is what it claims to be.EUCHARIST & SERVICE TO THE POORIt may be objected - outside this room byliberal friends, if not here in it - that thisEucharistic radicalism is not obviousenough and hence needs to be made so, inwords. We can keep working on the words,but I would rather say, after pointing outthat obviousness is not the first issue, thatthe character of the Eucharist could bemade even clearer in action.1 7R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

The ancient Church was renowned for itscare for the poor, and this has been amark of pride for the Catholic movementin Anglicanism. In early Christianity, thecare of the poor was embedded ineucharistic celebration, initially by bringingfood for the sharing of what was at theearliest point a substantial meal that,unlike many banquets of the time, did notreflect social locations in portions orcomestibles. Later it did so by the takingaway portions of what was a stillsubstantial meal to the housebound andimprisoned, and then later still by bringingfood offerings for our familiar symbolicmeal, the excess of which was distributedto the poor as substantial food. Ourtransformation of freewill offerings intosomething supporting the Church as awhole requires some correction I think,even if we do need those too. What if wesaid though, that a Eucharist was not validif it did not include some effort – even ifsymbolic, at the actual celebration – tofeed the poor? The fact that outreach issupported by our money offerings may notbe clear enough; bring a food basket,bring the packed lunches going out later inthe day, bring signs of the feedingprogram next door, make the connectionbetween the eucharistic food and thehunger of the world.As an aside, let me say I confess to a littleunease about the juggernaut oftheologizing about “abundance” I hear often; my concern or even cynicism is inresponse to the claim or assumption thatAmerican elites, who own most of theworld’s wealth, are rapacious because ofanxious about a scarcity of resourcesdespite their actual superabundance, andthus need to be assured with noises abouthow much stuff there really still is foreverybody. For reasons which include thelack of sustainability and moderation in ourconsumption, I would prefer a theology ofsufficiency.For various reasons, the engagement ofthe Church with the poor and hungry hasbecome variable at best; some of the mosteffective feeding programs seem to havelost an ecclesial dimension in the course ofbeing professionalized. We seem morelikely now to find a non-profit hiring spacein the Church to feed people, and thetenancy arrangement coming up mostlyamid talk of the Church leveraging itsassets, than to find the wardens serving thesoup. I am sure you can offer me goodexceptions, and I am not wanting to caststones; but where this is good, we shouldcelebrate it, and where it is not happening Isuggest we need to reverse that trend andto reclaim the sacramental character ofcharity itself as direct action.I am aware of the dangers that may beconnected to this, but I think they are worthentertaining. And if it is not obviousenough, let me make explicit the 1 8R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

eucharistic connection. The Mass depictsand enacts a world in which all are fedand all have enough. If we refuse to live inthat world when we have communicated,we are blaspheming the Eucharist. Toparaphrase Bishop Frank Weston, “Youcannot claim to worship Jesus at thecommunion rail and refuse to serve him inthe soup kitchen.” [1]This recognition, as well as the realanswer to the “open communiondilemma,” entails understanding ourselvesas just as much in need of grace andprogress in holiness as those whom weserve and evangelize. This is notnoblesse oblige; it is, as Sri LankanMethodist theologian D. T Niles put it,“one beggar telling another beggar whereto get food.” [2]THREE CONCLUDING WORDS:FRANK, JOHN, AND WOODYThese thoughts about baptism andEucharist constitute an incompletesuggestion that I hope the Catholic wingof the Church can develop amid the ruinsof civil religion. The problem withprogressive Social GospelEpiscopalianism is not that it is tooprogressive, but rather that it is notgenuinely radical enough. The Gospelmakes radicals; and it is not the Churchthat will save our society if anything will,but God, presumably through people of all faiths and none, but including Christianswhose profound understanding of theGospel enables them to act as citizens,workers, who claim what is theirs, and therights and needs of all.I alluded to Frank Weston’s rallying cry atthe 1923 Anglo-Catholic Congress. Thiskind of insight about the connectionbetween the Eucharist and justice is anancient one. John Chrysostom notablysaid, in reference to the Eucharist and tocharity for the poor:You honor this altar, because it receivesChrist’s body; but the person who is theactual body of Christ you treat withcontempt.... That altar you can see lyingin lanes and in market places, and youcan sacrifice upon it every hour; for onthat too sacrifice is performed. And asthe priest stands invoking the Spirit, soyou invoke the Spirit, not by speech, butby deeds (Homilies on 2 Cor., 20)So strikingly John says the Christianengaging the needs of the poor iscelebrating their own Eucharist too. Onecorrective John and the tradition thus mightoffer Bishop Frank is that they did notpresent action for the poor as “pity,” but asworship. John suggests his well-offChristian audience needs the beggar-altar,as much as the reverse. So both these altars, that of the Eucharist 1 9R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

and the bodies of the poor, are sacredplaces and places of socialtransformation. This is already the case,but we can make it plainer. WoodyGuthrie’s guitar was famouslyemblazoned with the words “this machinekills fascists” -- our chalices andmonstrances and aspergilla and ciboriamight all be engraved “this machine feedsthe poor.”Andrew McGowanNew Haven, CT[1] The original was of course “You cannot claim toworship Jesus in the Tabernacle, if you do not pityJesus in the slum”; see Frank Weston, “OurPresent Duty,” n.d.,http://anglicanhistory.org/weston/weston2.htmlAccessed April 20, 2020.[2] Daniel Thambyrajah Niles, That They MayHave Life (New York: Published in association withthe Student Volunteer Movement for ChristianMissions by Harper, 1951), 98.2 0R E N E W I N G T H E A N G L I C A N C A T H O L I C S O C I A L T R A D I T I O NT H E H O U R

On Advent 1 of 2017, I walked into what isnow my home parish, and for the first timesince I was a child, I was in a mostly-Black church. I felt at home. I wassurrounded by worshippers who lookedlike me, who smelled like my parents, andwhen I walked to the altar rail to take partin Eucharist, given to me by layeucharistic ministers of all ages andraces, I knew I’d make the EpiscopalChurch my spiritual home.In January of 2018 we had a bishop’s visitwhere a white woman (for a reason I’mstill not sure of) told a room full of mostlyworking-class, Black and Latinoparishioners, who just wanted to knowwhy it was so hard to find a rector whomight look like us, that there was no way aperson could live in Austin being paid$60,000 (not that it matters, but we wereoffering far more than $60,000 a year). Atthe time, I made around $9,750 a yearbefore taxes. And I felt like, "oh no, maybethis isn’t my home." But our parishshowed me that we can call in those wewant to be our allies. We forgave hermisstep and we now have a spirituallyfulfilling and loving relationship with ourcurrent rector.So today, I’m writing in hopes of callingyou in, offering forgiveness, and perhapsmoving forward to a more spiritually fulfilling and lovingrelationship with the Blackmembers of your dioceses. InDaughters of the King, werecite the motto of our orderat each gathering, saying,"What I can do, I ought to do.What I ought to do, by thegrace of God I will do." Irespect the office of bishop,and that’s why I feelconvicted by God to say this:All Episcopalians deservemore.2 1T O A L L B I S H O P ST H E H O U RRecent official statements sent out bybishops have, to say the least, hurt medeeply. After reading my own bishops'statement once, I had to use the searchfunction on my computer because clearly Ihad to be mistaken—there was no way,after a weekend of unrest due to the sinsof anti-Blackness and white supremacy,that my bishops would release astatement without affirming that theybelieve Black lives matter. And yet, itdidn’t happen. The word "Black" in fact, isnot included once. To acknowledge thesin of racism without noting that in itsAmerican context it is deeply rooted in

2 2T H E H O U Ranti-Blackness, is specifically to makeanti-racist conversations easier for whitepeople. Especially troubling were the listof affirmations and condemnations. Notonly were Black people placed under theumbrella of "people color"—and mydiocese knows especially well that Blackpeople have a specific relationship towhiteness that needs to be named(myown parish was founded because of thatrelationship)—the bishops stated theirsupport exclusively for peaceful protests.Do you know who wasn’t a peacefulprotestor? Jesus. Do you know who alsocondemned the destruction of property?The white moderate and "progressive"clergy members of Alabama who calledfor "law and order," and who inspired Rev.Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to compose hisLetter from a Birmingham Jail where hewrote:"the Negro's great stumbling block inhis stride toward freedom is not theWhite Citizen's Counciler or the KuKlux Klanner, but the white moderate,who is more devoted to "order" than tojustice; who prefers a negative peacewhich is the absence of tension to apositive peace which is the presence ofjustice; who constantly says: "I agreewith you in the goal you seek, but Icannot agree with your methods ofdirect action"; who paternalisticallybelieves he can set the timetable foranother man's freedom; who lives by amythical concept of time and whoconstantly advises the Negro to wait for a "more convenient season."Shallow understanding from people ofgood will is more frustrating thanabsolute misunderstanding frompeople of ill will. Lukewarm acceptanceis much more bewildering thanoutright rejection."People do not riot who do not have areason to riot. When our Lord turned overthe tables in the temple, it was a reminderthat things do not matter. We cannot takeour things with us to heaven. Our propertywill bring us no closer to Christ. In thebishop’s letter we were called to be ourvery best Christian selves, and yet werecalled to value property more than thepain of people who have destroyed thatproperty.You reminded us to pray, and then calledus to act. And I agree—prayer, especiallythe Daily Office, has been such a balm tomy spirit lately. When the church calendarmoved us from Eastertide to the seasonafter Pentecost and we once again beganour services by confessing our sinsagainst God and our neighbor, a reliefwashed over me. Before we pray foranything else, we confess. We all need toconfess, but it feels disingenuous andfrankly un-pastoral to not even mentionthat those who benefit from whitesupremacy need to repent and confessthose sins. We cannot pray for peace orjustice before we confess. Our prayerbook shows us that. Our action needs tobe rooted moving forward from that sin.

2 3T H E H O U RThe church does have a responsibility tospeak out when people are not protected,and part of that responsibility is namingthe people, naming the sin: anti-Blackracism, white privilege, white supremacy.These are not partisan political terms,they are sins. Why would you not call usto name them?A specific statement put out by theDiocese of Texas quoted ArchbishopDesmond Tutu in its appeal, saying, "Hebelieved that nonviolence presupposes aminimum moral level of the state." Thestate has not, on multiple occasions,including the violent gassing of protestorsnear St. John’s Episcopal Church in theDiocese of Washington, D.C., shown usthat they are operating at any moral level.People do not get grabbed off the streetsin unmarked vans in a moral state. Therehas to be morality for there to be non-violence. To say otherwise is to tell peopleto martyr themselves, and while I like St.Joan of Arc just fine, are you willing tomartyr yourselves? Show us beforecondemning our righteous anger.The sentiment that we must be thegeneration to end racism in all forms ringsloudly in many pastoral letters I've readfrom bishops all over the country. Amenand amen. But, as I have stated, to endracism, we need to name the sin of whitesupremacy. Dear Bishops, have you donethat? Or did you submit guidance claimingto be non-partisan, but was actuallyincredibly centrist, in order to keep the deans of your cathedrals and their majordonors happy? We should be upsettingthose in power. We cannot serve Christand white supremacist notions of propertyrights. We must choose. When Jesus toldus to take up our crosses and follow him,he did not intend for it to be somethingthat made everyone around uscomfortable. The cross of every Christianshould be heavy with grief at the sin of theworld, especially when said sin is done inChrist's name. As we drag them throughthe streets, people should stop and gawkand feel convicted to change. Have youoffered guidance that keeps moderateshappy? Or are you really seekingsolidarity with those who most desperatelyneed to hear Jesus' message?Jesus spoke for the least of these. Hesaid blessed are those who are poor inspirit, who mourn, who work for peace,and who are persecuted for righteousnesssake. The Episcopal Church at large hasso much work to do to become theBeloved Community. We have centuriesof ties with America’s imperialism andcolonization, including our role as aslaveholding denomination. For us tomove forward, we need to focus on thosewho we’ve harmed more than those whohave always been in power. "You are thesalt of the earth; but if salt has lost itstaste…it is no longer good for anything."Let us be salty. Let us be useful. Let usname and condemn sin loudly, and standwith those it might seem uncomfortable tostand with, even if they do end up

2 4breaking a couple of our stained glasswindows. Let us do better, in Jesus’name.FOR HIS SAKE,Ari L. Monts Austin, TXT H E H O U R

T H E C R I T I Q U E O F N A T U R E A N D C H R I S T I A NS O L I D A R I T Y W I T H B L A C K L I V E S M A T T E RThe demand for justice that issues fromBlack Lives Matter is a sufficient warrantunto itself to demand the full solidarity ofChristians. What follows should nottherefore be taken to suggest that acertain theological investigation --especially one coming from a white manlike myself -- is in any way “necessary” forChristian solidarity or that BLM’s demandfor justice is somehow deficient until it’s“approved” by theology. In fact, it isprecisely the opposite that is the case.However the scourge of racism appears tothe eyes of faith, it is crucial thatChristians keep in view the fact thatracism is an entirely this-world problem,intelligible and therefore available forabolition on its own terms. Unfortunately,much of the overthinking and ambivalencethat plagues the (white) Christianresponse to racism stems in part from afailure to recognize this fact; afundamental misidentification of the kindof problem that racism is.Excursus. It is a truism on the left thatcapitalism stands out for its remarkableability to distort our perception of things.Furthermore, because it arises from withina Christian imagination, capitalism gains a significant amount of its endurance andplausibility from the manner in which itreconfigures certain claims of Christianity.For instance, consider how capitalism ispredicated on the doctrine of the Fall. Ifliberal rationality presumed to understandthings as they “really are,” then the socialrelations as imposed by capitalism werelikewise understood to simply be the“natural” relations of human beings. Butthis required a conflation of what Christiantheology had at least traditionally keptseparate. No matter how thoroughlypervasive the effects of the Fall were onthe human race and the creation in whichit lived, the Fall was neverthelessconsidered to be a defect of a priorintegrity. However, capitalism makes thisdefect constitutive: the distinction betweenhumanity as originally created andhumanity as depraved by sin is effectivelyerased. Having collapsed the competitiveimpulses of an estranged and alienatedhumanity into the nature of things,capitalism constructs a new natural law, anew realm of neutrality. As a result, whilemoral judgments about those impulsesare still permitted, they are limited merelyto what are seen as the deviations -- WITHOUTEXCUSE2 5T H E H O U R

2 6T H E H O U Rwhether of excess or deficiency -- of whatis otherwise stable and natural (astandard of judgment that has incidentallyproven most useful in the racialcategorization of black people vis-a-viswhite people). Morality is thus permitted tojudge only the exceptions to the rule; and,as we learn from Augustine’s idea of evilas a privation of the good, exceptions areneither inherent nor essential to theircorresponding norms. Moral judgments ofcapitalism’s sins thereby serve toreinforce the normativity of capitalist socialrelations and human conduct [1]. Becausecapitalist social relations are located in apublic realm of facts -- and are therefore“natural” -- those relations themselves arenecessarily exempted from moraljudgment, since moral judgments areconversely located in the private realm ofindividual preference.The irony, however, is that far fromabolishing Christianity, this bifurcationoffers it an enticing role to play in theliberal-capitalist order. Christianity willalways have job security under capitalismbecause, as a private matter itself, religionis tasked with the moral regulation ofindividuals that disciplines them intoproper capitalist subjects. Once confinedto their properly private realm, bothreligion and moral judgments alikeperform a vital function in themaintenance of capitalism. But religiondoesn’t merely perform this task asthough it were an assignment sent downfrom upper management. On the contrary,religion internalizes this task into itstheological imagination. Our doctrine, ourchurches, even our account of “theGospel” itself, are aligned with this task soas to produce a mutually reciprocalrelationship between capitalism andreligion.I begin with this excursus on capitalismbecause it is essential for understandingthe difficulty of (white) Christians toproperly identify the kind of problem thatracism is. After all, as the theory of “racialcapitalism” as developed by CedricRobinson suggests, it is doubtful thatcapitalism and racism were ever separateto begin with (see also Willie JamesJennings on this point). So, the manner inwhich many Christians across the politicalspectrum attempt to address the problemof racism reveals that our theologicalimagination is coextensive with capitalistlogic.“Sin” is a theological category, even forprogressive Christians who readily admitits “systemic” dimensions. But recall that,under capitalism, to identify somethingtheologically is to categorically remove itfrom facts, from nature, from politics. It isto immediately frame it as somethingseparate from the world and society, andtherefore as something that isunintelligible apart from the “private”claims derived from divine revelation. So,to identify something as “sin” is to

2 7T H E H O U Rtranspose it into an otherworldly key,inadmissible to the world on its own terms.Granted, this theological account has alongstanding precedent in certain streamsof the Christian tradition that are notreducible to capitalism. Indeed, not farbeneath this whole discussion is theperennial question concerning therelationship between nature and grace.But the affinity between this theologicalaccount and the capitalist conception ofnature is nevertheless significant, as thelogic of capitalism maps the distinctionbetween nature and grace onto thedistinction between public and private.Consequently, if one accepts theconfiguration of religion as established bycapitalism, then a theological categorysuch as sin becomes an incrediblyconvenient tool with which to mystifycapitalism’s manifold injustices, racismincluded.For American Christians, the claim thatracism is a sin is hardly controversial.What is hotly contested is rather the kindof sin that racism represents; it is, in short,a dispute about whether racism is a“systemic” sin as opposed to a “personal”sin. And yet, our consensus about thesinfulness of racism leads inexorably to afurther consensus about the kind ofsolution that Christianity proposes.Whether conservative or progressive,some account of “the Gospel” is what isnearly always put forward as what oursociety needs to overcome its affliction of racism. And this makes sense for areligion that hopes for the redemption of asinful world. But what this fails to examineis the nature of sin itself, as well as whatwe are saying when we identify the “sin”of racism. It too often takes for grantedboth the construction of nature underracial capitalism and the correspondingprivatization of religious claims, havinginternalized both under the guise oftheology.What this looks like in practice is whenChristians routinely assume that if racismis a sin, it must necessarily be some kindof ineffable evil that is ineradicable withoutthe redemption offered by “the Gospel.”Even if one grants the historical andstructural conditions of racism, themoment that racism is identified as a sin,it effectively becomes a problem whosesolution can only be seen with the eyes offaith -- a private vision. Note how oftenBLM is framed as something that has tobe “related” to Christianity, as if from theoutside, as opposed to something thatmay be already incumbent on us simplyas human beings. And it’s irrelevantwhether it is related positively ornegatively, because in either case, manyChristians -- particularly those who arewhite -- remain unable to account forBlack Lives Matter except from a positionthat is theologically detached from itspolitics: a detachment that presupposesthe racialized exemption of white peoplefrom the demands of BLM even as it

2 8T H E H O U Rstrives to induce in them a spiritualizedsolidarity as white Christians. The attemptto build support for the cause of blackliberation upon exclusively theologicalappeals -- such as to the “sinfulness” ofracism -- can mask an unspokenadmission that there are no other appealsthat can be made. To put it in Ibram X.Kendi’s terminology, even if Christiansreject the “racist” belief that “problems arerooted in groups of people” -- as opposedto the “anti-racist” belief that “locates theroots of problems in power and policies” --the problem is that sin is rooted, if not inselect groups of people, at least in peoplegenerally [2]. Sin only pertains to “powerand policies” to the extent that peopleimplement or reinforce them (since powerand policies are incapable of committingsin on their own), which is why theexclusive framing of racism along the linesof sin/redemption disqualifies it from beingproperly “anti-racist” as defined by Kendi.Without the necessary critique, theconcept of “systemic sin” can getdistracted by precisely the kind ofindividualistic moral conduct that it seeksto transcend. And this happens to playright into the hand of the conservativeChristian reaction against BLM byneedlessly entangling the naturalimperative to abolish unjust structureswith the spiritual drama of sin andredemption.Now, I would be at risk of succumbing tothe very bifurcation I’ve already critiqued if I were to claim that Christianity hasnothing to say about the problem ofracism. To bracket our theological critiqueof sin from our solidarity with the politicsof Black Lives Matter would simply be tohop on the opposite side of the capitalistpartition that’s imposed between religionand politics. So, perhaps it’s moreaccurate to say that Christians are in needof better theology than a wholesaledismissal. Nevertheless, when it comes tothe problem of racism, this better theologywill be marked by a respect for theintegrity of a thoroughly “natural” politicsof abolition and the moral obligations thatfall upon us as humans. And even if weregister it as a “sin” (which we absolutelyshould), the effects of this sin will still bethose whose abolition need notnecessarily involve the gift of grace. Theracist sins which induced the managers ofwhite supremacy to implement itsstructural dimensions may in fact be sograve that only the power of God canredeem (or damn) them, but fortunatelyfor us, those structural dimensions are notso ineradicable. Nor do we need stand byas we wait patiently for the piecemealrepentance of every white person’scomplicity, as though the structures ofracism were the symptoms of individualsensibilities and not the other way around.That isn’t to say that the personal sins ofracism aren’t formidable in their own rightor that they can always be neatlydetached from racism’s structuraldimensions -- there’s certainly a reciprocal

2 9T H E H O U Rrelationship between the two. And withinthe church we should be most vigilant indisciplining any vestige of racism as agrievous sin. But even still, the appeal toChristians for the abolition of racism as astructure of injustice must begin not with“sin” or any particularly “theological”category at all, but with a critique of theconcept of “nature” as established byracial capitalism -- a critique that isaccordingly rooted not in theology, but in arival political account of nature such asthat put forward by Black Lives Matter. Forit is the presumption that these structuresrepresent the inviolable laws of nature thatleads us to imagine that only a divineinjection of an otherworldly grace canabolish, if not the structures themselves,at least the private sins of the individualswithin them. In short, Christians accessthe politics of BLM first as humans,accountable to the demands of justice thatare discernible within the natural orderalready -- we are indeed "without excuse"(Rom. 1:20) -- and only secondarily asChristians who are accountable to theeven higher standard of discipleship.Perhaps I’ve made my point already. Thatthe response of so many white Christiansto Black Lives Matter is one of cynicismand resignation reveals just howinsignificant their inner dispositions are tothe abolition of racism. However,notwithstanding the incredible capacity forreactionary violence that cynicism andresignation possess, this response is ultimately one of disavowal: it is the onlyreaction left when the sheer artificiality ofracism is exposed for all to see. Which isjust one of the reasons why Christiansshould concede that, with regard to theabolitionist politics of Black Lives Matter,we aren’t induced to participate for anyspecifically “Christian” reasons. Far fromimpugning our theological vision or theredemptive potential of the Gospel,however, this concession witnesses totheir radical clarity. The humanity of thosefighting to dismantle white supremacy isas conspicuous as the structures thatmust be dismantled -- which is more thanconspicuous enough. Our theology lendsits greatest solidarity by refusing toobstruct the view.Caleb RobertsPonca City, Oklahoma[1] Mark Fisher. Capitalist Realism, 16.[2] Ibram X. Kendi. How to be an Anti-Racist, 9.

Summer 2020 exploded into turbulence asthe pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic,and the ongoing racist brutality ofAmerican police led to widespread andcontinuing protests. It is a moment ofunrest and, perhaps, also a moment ofrenewal. As many have noted, thepressures of this year are functioningapocalyptically, revealing deep-seatedinequities that have been invisible toolong. As these inequities are revealed,how will we respond?I am a prison abolitionist and a Christian.What I have learned from the organizersand activists who came before me is thatsystemic change will not necessarilydevelop from unrest unless we guide it,imagining what could be from cleardiscernment of the specifics of the currentreality we fight. And what my faith teachesme is that the Christian story and the hopeof the coming kingdom of God, madepresent in Word and Sacrament, offers aprofound basis for such revolutionarywork. But too often that potential issquandered as the church shies awayfrom specifics in moral reasoning and radical imagination in sacramentalpractice. In this moment of tumult, I callupon the church to respond in a way thatonly the church can: by using Word andSacrament to witness to and practice arevolutionary specificity that will supportand expand our moral imagination andour work of radical solidarity.Abolition requires a new moralimagination. The reality of abolition is thatit requires not only that we build power todismantle unjust structures and developalternatives, but that we cultivate animagination expansive enough not torecreate the problems we are trying tosolve. Organizer Mariame Kaba says thatthe cops are “in our heads and in ourhearts” and we must remove them fromour imagination of what’s possible beforewe can undo our reliance on policing,prisons, and carceral structures in oursociety. Dr. Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts itthis way: “Abolition requires that wechange only one thing, which iseverything.” In my own abolitionist work, Ihave learned that the conceptual gap isas difficult to confront as the organized S P E C I F I C I T Y& M O R A L I M A G I N A T I O N3 0T H E H O U R

3 1T H E H O U Rresistance. I educate about abolition froma Christian standpoint for the church—andI am heartbroken every day by how far wehave to go, and by the paucity of ourimagination as a church when it comes tothe matters of justice: Which is, as CornelWest says, “what love looks like in public.”What do I mean by the paucity of ourimagination? I mean that almost nochurches are willing to make a pledge notto call the police. I mean that ourresponse to unhoused people living onour property is too often to put up securitycameras, to fear for our property over theirlives, to prioritize the safety of otherstakeholders who use our campusesthrough “official” channels over the dignityof the most marginalized. I mean that ourresponses to abuse and misconduct in thechurch rely heavily on mandated reportingto civil authorities and thereby oncooperation with the carceral state and itsdeath-dealing powers. I mean that I havelearned far more about accountability,including how I take accountability fordoing harm myself, from secularpractitioners of transformative justice thanI have ever heard preached in church. Imean that our understanding of ourcommunity ministries is still bound up inoutdated conceptions of “outreach”whereby we (presumed rich) provide forthose who are “less fortunate,” rather thanby understanding our work in thecommunity as grounded in our mutualneed for one another and building new forms of mutual aid with ultimatelyrevolutionary aim. I mean that we claim tobe able to imagine the coming of thekingdom of God—but we don’t seem to beable to imagine that justice doesn’t haveto involve punishment or that we have thecapacity to care for one another withoutreliance on violent state systems.The ethical role of the church is to developmoral imagination. The church exists asthe first frontier of the kingdom of God, atthe boundary between the comingkingdom and the world under the sway ofthe powers of death. As an outpost of theinbreaking reign of God, the Church’s roleis to interpret to the world the new life ofgrace, the new way of being in freedom,the ultimate liberation of the cosmos. Thishas aspects beyond the ethical, but on theethical level, this ultimacy of freedomlooses our imagination for newpossibilities. To do Christian ethics isprecisely to do imaginative ethics, to letthe newness and absurdity of the gospelbreak down the walls in our thinking andnourish new possibilities of love anddivine freedom.We develop and practice such imaginationin our life together through Word andSacrament.The word of God, applied to our materialcircumstances, offers a radical resourcefor developing a revolutionary moralimagination. But for the word to do its

3 2T H E H O U Rwork of expanding our moral imaginationrequires specificity. Our imaginationexpands in the places where our values,put into action and applied to specificsituations, challenge the status quo. Thecall to “love our neighbor as ourselves,”without specificity, is inspiring, but the callto apply it to our particular neighbors andto material systems of oppression iswhere we find growth in imagination.What does the Great Commandment sayabout my responsibility to an unhousedperson sleeping in the alley behind myhouse—not about the need to “findsolutions to homelessness” in general, butabout what I do in that moment for thatindividual, knowing that I am housed andthey are not? What does it say about myresponsibility to avoid calling the police onsomeone if that might risk their life? Whatdoes it say about my individual, personalresponsibility to support systemic changethrough mass decarceration in a time ofdangerous pandemic, remembering thosein prison as if in prison with them (Heb.13:3)?The new life of the reign of God isconstantly breaking into our reality inconcrete and specific ways. To develop anew moral imagination through the wordrequires that we name those specificsprophetically and hopefully, identifyingwhere the newness of God is alreadypresent in works of resistance and namingas deadly the specific ways of the status quo that we have too long accepted. Tolearn such specificity requires that we lookto the work of marginalized activists andfollow the lead of those most directlyaffected by systems of oppression,building true relationships of proximity andmutuality (in the eloquent language ofattorney Bryan Stevenson and Fr. GregBoyle).I believe there is a desire in the church forethical specificity. Episcopalians famously,and frustratingly, tend to base all ethicalreasoning on one vow from the baptismalvows in the Book of Common Prayer: “Willyou strive for justice and peace among allpeople, and respect the dignity of everyhuman being?” (p. 305). I say frustratingly,because on its own, this vow is notspecific enough to guide every ethicaldecision—and yet, at the same time, thecurrent Baptismal Covenant was written toexpand, in specific terms, on thetraditional vows to renounce the powers ofevil and follow Christ as Lord and Savior.[1] Perhaps the reason the most modernof our baptismal vows is the mostfrequently-referenced one is that it meetsa real felt need for specificity in ethicalguidance.And yet, continuing to develop suchethical specificity remains a struggle. Wename the need to love our neighbor; wename the need to fight against racism; wename the need to resist massincarceration, but we do not want to be so

3 3T H E H O U Rexplicit as to say, over and over, in everycongregation, that fighting racism meansdefunding the police, because it requiresfollowing the lead of local activists whoare most directly affected, and making thesame radical demands they are making.Resisting mass incarceration, as followersof the one who came to set the prisonersfree (Luke 4:18) means naming abolitionas our goal—not naming vague “reform” inorder to leave an out for those who wantto maintain a retributive, carceral systemfor those it’s easiest to hate. We arewilling to say with Jesus, that you cannotserve God and Mammon only because ofthe distance imposed by the archaiclanguage, which provides safety invagueness. We won’t go as far as totranslate it into modern terms and modernmaterial conditions, to say: “You cannotfollow Jesus and support capitalism.”Our lack of specificity means that ourethical witness grinds to a halt at thelowest common denominator, as we offerunobjectionable consensus statements inplace of specific applications of the Wordof God. And our specificity means that weare not pushing each other, in our livestogether in the church, to expand anddeepen and challenge our moralimagination. Broad stroke statementsallow each of us to find a place ofagreement within our currentunderstanding; but removing the copsfrom our heads and our hearts, building amoral imagination that truly follows Jesus on the “narrow way” that leads to life,requires that we name our goals, ourvalues, and the radical way of love inspecific, challenging, and controversialterms. “Whoever has two cloaks must giveto one who has none.” What do we eversay today that is equally clear, equallyspecific, or equally difficult?Specificity is also cultivated symbolically.Our sacramental life provides anotherlocus for expanding and enacting ourmoral imagination as the new life in Christcollides with the present reality—but onlyif we let the specifics of material realitiesaffect how we imagine our sacraments inlife-giving ways.At the same time as the pandemic hasrevealed the underlying inequities of oursociety in bright-line color, the necessity ofsocial distancing threw our liturgical andsacramental symbols into question. As weare forced to rethink what our sacramentalsymbols look like, how can we take thisopportunity to let our creative moralimagination—nurtured by specific calls tojustice, and in specific contexts—reformour sacramental practice?The beauty of sacraments is that they notonly speak but also act directly throughtheir form and practice. As WilliamCavanaugh writes, the Eucharist is notprimarily a way of symbolizing politicalmeanings but a counter-politics thatmakes us “engaged in a direct

3 4T H E H O U Rconfrontation with the politics of theworld.” [2] The sacraments let us gropeand fumble toward making real what weenvision with our expanded moralimagination: what Gilmore calls“rehearsing the revolution” again andagain. But for our sacraments to be aneffective rehearsal of the revolution andan effective counter-politics requires thatthey be grounded in the imaginative ethicsborn out of specific contexts andcommitments.Remote distribution of communion duringthis pandemic—through (safe andsocially-distanced) eucharistic visitation orother means—offers such a visiblereimagining of sacramental practice,emphasizing as it does the ways in whichabsence is always inherent in asacrament that presents Christ at themoment of his abandonment by God insolidarity with what Ignacio Ellacuría calls“the crucified peoples of the world.” AsJesus says right after instituting theEucharist, “You will all become desertersbecause of me this night; for it is written, ‘Iwill strike the shepherd, and the sheep ofthe flock will be scattered” (Mt. 26:31).Our dispersion, perhaps, brings us closerto Jesus and the earliest Eucharisticpractice than our triumphant gatheringsdo, as it forces us to experience concretesolidarity with those absent because ofinaccessibility or oppression. Communion-in-dispersion helps us to imagine ourcommunities as transcending those able to gather in worship, and shows usChrist’s body as he is really present inthose marginalized and excluded to thesame extent as in the bread and wine.But for such a sacramental practice toform a meaningful counter-politics in ourcurrent context, it must also be groundedin acts of concrete solidarity with thosewho are marginalized and excluded. Thespecificity of the Word, calling us toradical ethical action, empowers ourpractice of the sacraments to enact acounter-politics of solidarity. The specificsof the context and the radical call to actionin the wider community provide thefoundation for the symbolic practice ofsacraments.Another example comes from disabilitytheology. Nancy Eiesland writes that “theeucharistic practices of the church mustmake real our remembrance of thedisabled God by making good on bodypractices of access and inclusion.”[3] Ourpractice of Eucharist in a time ofpandemic requires us to first be open tosuch access and inclusion with (for thoseof us who are abled, new and too long incoming) fresh urgency. We mustinvestigate and meet the access needs ofthose in our communities—bothaccessibility for disabled people, andaccess to the technology which mediatesour current forms of worship. A Eucharistgrounded in such specific practices ofaccessibility becomes a work of