Return to flip book view

Annual Report 2023

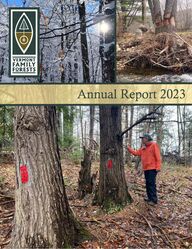

watersheds settlers soon created by building steep roads, clearing streams of woody debris for waterpower dams, and turning the forests into fields and the trees into boards, firewood, and potash. Though relatively young forests have returned to blanket 75% of Vermont, our rivers and streams are still flashy and brown with sediment even after light storm events, both because of the enduring impacts of those settlement-era changes to the land and because we continue to build steep, erosive roads and inadequately maintain them. Fast forward to January 10, 2024, when I was pondering this annual report and reflecting on the past year. The weather forecast that day was for high winds, and I wondered how many trees would blow over and what landowners would do in response. As predicted the wind howled all night here on Colby Hill in Lincoln. It came in with gusto at about 9 pm and it was still blowing hard when I woke at 3:50 am. I sent a note to loved ones hoping they were all tucked in and safe. I went back to bed with Aldo Leopold’s “For the Health of the Land – The Farmer as a Conservationist” in my hands. If the gully-washing storm events that hit Vermont in 2023 left any doubts, the two back-to-back wind events at the outset of 2024 removed them. Faced with rapid climate change, we must step up the pace of changing the ways we interact with our forests. How? By adopting an Earth-centered world view and conserving our family forests accordingly. By moving away from a focus on timber and utilitarianism. There is nothing standing in the way—if we have the will to listen to our hearts—of creating an ecological ethnicity in the watersheds of home. Seeing the family forest owner as a conservationist first is one radical element. This report shows what Vermont Family Forests was up to in 2023 to do just that. May the forest be with you! The Family Forest Owner as a Conservationist Someone recently asked me about the spelling of one of the words in our mission statement. Isn’t it “holistic,” rather than “wholistic”? While both spellings work, for me there’s no question which one reflects what we’re up to at Vermont Family Forests. When you find yourself in a hole, stop digging, as the saying goes. It’s a no-brainer. Yet here we are. Climate change is breathing down our necks and blowing down our trees. It’s time to put down the shovel and move from the hole to the whole. 2023 brought gully-washing storms that inundated our beloved state capital in July. Atmospheric rivers drenched this side of the Green Mountains in August, and Route 116 was closed for months because of it. Microbursts tore through saturated forests and toppled trees. Heavy rain barreled down steep forest roads and washed them into streams and on to Lake Champlain. Vermont’s hottest year on record, 2023 was an exceptionally challenging year to be a standing tree in Vermont’s Center-West Ecoregion. Back in the earliest days of Vermont Family Forests, in the winter of 1996, I invited forty forest landowners to a gathering at the Old Bristol High School. I was the Addison County Forester at the time, and the invitees owned a diverse array of forest parcels scattered around the county. That evening, with food and drink and in a lovely gathering place, we explored the idea of cultivating an organization of “family forests” that was truly different from Tree Farm. Our organization would put forest health first—above, before, and beyond wise use. As I settled my nerves and organized my thoughts before speaking, I pondered what it was that the participants of this gathering had in common. I knew every person in that room, and it was at once obvious to me that every one of them wanted to do right by their forest. Why? Love of the land. It was from that fact that VFF’s Organic Forest Ecosystem Checklist grew, spelling out measurable, tangible, hands-on ways landowners could put their love into practice, then and to this day. When, in 1609, Samuel de Champlain paddled up the lake that now bears his name, the mountains he saw to the east weren’t simply green ones, they were verdant. The watersheds then were spongy catchments, not the ditched Conservation means harmony between [people] and land. When the land does well for its owner, and the owner does well by the land; when both end up better by reason of their partnership, we have conservation. When one or the other grows poorer, we do not. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 David Brynn Executive Director Vermont Family Forests Main cover photo: Chris Runcie repaints the boundary lines of her Starksboro family forest.

Observe, understand, and preserve forest ecosystem health, Practice forest-centered conservation that is wholistic and adaptive, Support careful management of local family forests for ecological, economic, and social benefits, and Foster a forest culture focused on community well-being, ecological resilience, and the quest of an optimal land ethic. Our Mission Conservation, therefore, is a positive exercise of skill and insight, not merely a negative exercise of abstinence or caution. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 2024 marks the 75th anniversary of Aldo Leopold’s seminal essay, The Farmer as a Conservationist. In it, Leopold makes the case for conservation rooted first and foremost in the skillful use of heart, head, and hands. He champions conservation motivated by curiosity and affection rather than fear, conservation that results in mutually beneficial relationship with the whole land community. Every bit as relevant today as when he penned them, Leopold’s words reflect the aim of all we do at Vermont Family Forests. First delivered as a talk at the University of Wisconsin in February, 1939, the essay is included in The River of the Mother of God and other Essays, by Aldo Leopold (University of Wisconsin Press). We’ve included many excerpts from Leopold’s remarkable essay throughout this annual report. Photo: Forest landowner Annie Wilson measures the diameter of a white pine in her Cornwall forest. Taking a Leaf from Leopold 3

2023 marked the 26th year of the Colby Hill Ecological Project (CHEP) biological inventory and monitoring on Vermont Family Forests’ Anderson lands in Lincoln and Bristol. During the 2023 field season, members of the CHEP research team gathered data on snakes, birds, large mammals, and water quality. Above: Vermont Family Forests Executive Director David Brynn looks on as CHEP herpetologist Jim Andrews examines an Eastern milksnake while monitoring the snake transect at VFF’s Guthrie-Bancroft land in Lincoln in October, 2023. Videographer Jill DeVito joined Jim’s team in the field and made a short video of their work. Below: Jim Andrews measures the length of a DeKay’s brownsnake. In the first 20 years of monitoring the CHEP snake transect on VFF’s Anderson Guthrie-Bancroft land in Lincoln, Jim and his research team, including Erin Talmage and Kate Kelly, never saw this species. Since 2020, his team has found DeKay’s brownsnakes here every year. According to Jim, this might result from climate change (DeKay’s Brownsnakes are usually found at lower elevations), or from changes over time in the habitat surrounding the transect. Colby Hill Ecological Project Water Quality in the Watersheds of Home Measuring stream water quality can shed light on the health of the watersheds that feed those streams. How we care for land directly affects the temperature, clarity, and chemistry of nearby surface water. In 2023, we added Norton Brook to our water quality study, which already included Cold, Beaver Meadow, and Isham brooks. Volunteers from the Addison County River Watch Collaborative collected water samples to measure E. coli, temperature, phosphorus, nitrate, turbidity, and chloride (see map, right). The data showed that Norton Brook exceeded the other sites in phosphorus, nitrate, and chloride, and exceeded standards for total phosphorus, E. coli, and turbidity at least once during the field season. We test and monitor water quality because we want to know where to focus our conservation efforts to best improve the ecological health and flood resiliency of local waterways, wetlands, and water bodies. It is customary to fudge the record [of land degradation] by regarding the depletion of flora and fauna as inevitable, and hence leaving them out of the account. Conservation protests such a biased accounting. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 Vermont Family Forests supports research and monitoring that shed light on the ecological health of land within Vermont’s Center-West Ecoregion. By monitoring populations of forest flora and fauna, soil carbon, and water quality, researchers can identify changes and trends over time. One big reason we do this is to apply the emerging findings in ways that contribute to the health and well-being of forests throughout the region. Another reason? To recognize and share the beauty and abundance of the wild community we humans are part of. And to encourage landowners to notice, celebrate, and conserve the abundance and diversity of life in their own forests. 4

3 Beaver Meadow Brook sample site Isham Brook sample site Cold Brook sample site Photo, left: ACRWC volunteers collect water samples. Center: Map of VFF’s water sampling sites. Visit the VFF website to read the full 2023 water quality report, and any of our other Colby Hill Ecological Project research reports. Norton Brook sample site In 2023, Vermont Family Forests funded the research of Cindy Sprague of Sprague GeoScience to assess Eastern Ratsnake populations in north-central Addison County, including the Lands of the Watershed Center. Eastern Ratsnakes are listed as a State-threatened species and are rated as a high-priority, species of greatest conservation need in Vermont. Using “snake hotels” to monitor ratsnakes, and radio-telemetry to track their movements, Cindy is studying ratsnake den sites, which are critical to their survival. In 2024, she plans to install additional snake hotels in the project area and monitor the amount of sunlight and surface temperature at a known den to help determine what land management strategies might benefit this ratsnake population. Attuned to Forest Birds When CHEP research associates Peter Meyer and Glen Lower monitor birds in VFF’s Guthrie-Bancroft forest, they follow a route and data collection protocol established by Barry and Warren King in 1998. Because it adheres to the research methodology of the Vermont Center for Ecostudies’ Forest Bird Monitoring Project (FBMP), CHEP bird monitoring contributes to both local and statewide understanding of bird population trends. Forest bird observation takes a finely tuned ear, since most birds are observed by sound rather than sight. In 2023, Peter and Glen added three new species—Northern Parula, Red-winged Blackbird, and Northern Cardinal—to the 26-year transect tally, which now includes 60 species. Six of those 60 species have been observed every year: Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Eastern Wood Pewee, Veery, Red-eyed Vireo, and Black-throated Blue Warbler. Others, like Common Merganser and Mourning Warbler, made just a single appearance. Still others, like the Canada Warbler, occurred regularly in the early years of the study, but not in recent years. Annual monitoring helps researchers note population trends over time. You can read any of our CHEP research reports on our website. Supporting Critical Local Research Photo: “Willie,” one of the eastern ratsnakes Cindy is monitoring. Photo: Cindy Sprague Northern Parula, Andrew Weitzel Red-winged blackbird, Ashok Boghani Craig Zondag 5 Northern Cardinal

VFF conservation forester Ralph Tursini works with dozens of family forest owners each year to create or update forest conservation plans for Vermont’s Current Use program. To do that, Ralph first observes and collects extensive data about the forest community—from the species, size, abundance, and health of trees to the condition of access paths and much more. These observations directly inform the conservation practices and management actions Ralph recommends. Our priority in every VFF forest conservation plan is to safeguard and, when appropriate, lend a hand in restoring forest health and vitality, following the optimal conservation practices spelled out in our Organic Forest Ecosystem Conservation Checklist. VFF conservation mapper Callie Brynn works closely with Ralph to develop the georeferenced maps that accompany each plan. Taking Stock of Family Forests Photo, left: Ralph notes the black bear claw marks on this serviceberry. Below: Ralph uses an increment borer to extract a narrow tube of wood that helps him determine tree age. Field observations like these inform every forest plan. 6

Vermont’s Use Value Appraisal (UVA or Current Use) tax program aims to recognize the public benefits of family forests by reducing property taxes in exchange for a commitment to keep the land as forest. For most of its 45-year tenure, UVA has recognized the timber values of forests, requiring enrolled landowners to cut trees and manage for forest products like firewood and lumber. For more than two years, David Brynn worked with a coalition of partners—Wild Forests Vermont—to expand UVA to recognize the public value of wild forests for carbon sequestration and storage, wildlife habitat, and flood and drought resilience. In 2022, the Vermont Legislature passed legislation creating a new UVA enrollment subcategory of Reserve Forestland, which went into effect in 2023. A step in the right direction, the Reserve Forestland subcategory remains out of reach for about 85% of forested parcels in Vermont, given its very narrowly defined enrollment criteria. We also have significant reservations about requiring manipulation of forests to achieve old-growth characteristics, rather than allowing forests to attain those characteristics naturally. On the plus side, the management requirements for qualifying parcels contain inspiring benchmarks for snag, den, and legacy trees, as spelled out in Restoring Old Growth Characteristics to New England's and New York's Forests (2022) by Tony D'Amato and Paul Catanzaro. In 2023, we used those recommendations to update minimum numbers for large trees, snags, and downed logs per acre in our Organic Forest Ecosystem Conservation Checklist. These benchmarks are our standard for every acre of every forest we work with. On page 10, you can read about how we put these benchmarks into practice in the forest. Hunter Perspectives Twenty-two hunters requested and received written permission to hunt on VFF lands in 2023. This annual process allows a back-and-forth flow of information and in-the-field observations, which allows for adaptive response to changing conditions on the land. At the end of each year, we survey hunters about their field experience and share information with them about the coming year. In response to data on bird population trends from the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, we removed ruffed grouse and American woodcock from the permitted hunting list at the end of 2023. Hunter Bob Patterson shared his insights on grouse decline, as well as a beautiful photo of a ruffed grouse nest on his own land, below. Part of the process of observing, understanding, and preserving forest ecosystem health involves learning from the research, work, and wisdom of others. VFF staff attended the Eastern Old-growth Forest Conference in New Hampshire, where an eclectic mix of people explored their shared passion for old trees and ecologically intact old-growth forests. Plenary speaker Bill McKibben gave the sobering reminder that if we don’t get climate change under control, all forests—old growth and otherwise—face dire straits. We took home renewed commitment to work here at home to help forests do their critically important work of sequestering and storing carbon, supporting biodiversity, producing clean water, and all the rest. The Ups & Downs of “Reserve Forestland” Eastern Old-Growth Forest Conference 7

What does it mean to be a good friend of the forest? Though that question has many answers, one thing we’re sure of is that it’s fundamentally different from being a good steward. Stewardship implies a top-down relationship and wise use of forest resources. Friendship implies mutually beneficial relationship, side by side, in it together—forestry as art, craft, and loving response rather than forestry that’s all about the science, which we are certain it’s not. One is taking care of, the other is taking care with. We have a lot of ideas of what it looks like to be a forest friend, and we test those ideas on our own lands. We also put our forest-centered conservation practices to work with the forest landowners we work with, as you’ll see over the next few pages. Being a Forest Friend Land, they say, is like a bank account: if you draw more than the interest, the principal dwindles. … Certainly conservation means restraint, but there is something else that needs to be said. It seems to me that many land resources, when they are used, get out of order and disappear or deteriorate before anyone has a chance to exhaust them. …Overdrawing the interest from the woodlot bank is perhaps serious, but it is a bagatelle compared with destroying the capacity of the woodlot to yield interest. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 In 2023, we continued to help turn ditched watersheds back into spongy catchments, both on our own lands and in the forests of the landowners we work with. Above, David Brynn’s outstretched arms show the original elevation of the land at VFF’s Abraham’s Knees parcel in Lincoln, before long-term erosion on this old, too-steep road carved a 5-foot-deep dugway. Such dugways are common across Vermont’s uplands. Whether such roads are actively used or long abandoned, they continue to suck water and sediment out of the forest and into nearby waterways, reducing both flood and drought resilience. Building durable erosion control structures ends this downward spiral. The steeper the road, the bigger the erosion structure needs to be to withstand gully-washing storms. In 2023, we remedied the issue at Abraham’s Knees. From Ditched Watershed to Spongy Catchment Left, excavator operator Andrew Cousino talks with David Brynn during a pause in his work building deep erosion control structure on the steep-sloped access road at Abraham’s Knees. Portions of the road exceed 35% grade. To fix this, Andrew dug 50 erosion control structures—from moderately contoured broad-based dips (effective on slopes less than 10%) to deep tank traps on steep sections—to send water off the road and back into the forest. We then seeded the soil with annual rye to anchor it until native plants take root. 8

In 2022, we built 80 road-closing erosion control structures on a very steep logging road on the Cold Brook land we had purchased earlier that year. A Vermont Youth Conservation Corps team followed up soon after the excavation was complete, pulling large, downed woody debris from the forest to help stabilize the soil. The photo, left, shows the road’s recovery a year later, in 2023. Fallen leaves further protect the soil like a bandage, allowing plants and microorganisms to naturally rewild the road. Though the contour of this steep road will remain on the land, the work we did ensures that the road won’t continue to funnel water and nutrients out of the forest. A Year Later During the process of gathering forest inventory data to update the forest conservation plan for the Town of Bristol’s Seth Hill Waterworks land in Lincoln, David Brynn saw an opportunity. Like so much land across Vermont’s hilly uplands, the Seth Hill Waterworks holds a legacy of steep roads that date back centuries. The roads have steadily eroded over time, carving deep dugways. In the photo, right, pink flagging indicates the original height of this forest road. Such dugways lace Vermont’s uplands, hugely changing water absorption and overland flow. The town of Bristol purchased the land as a water supply in 1905, and it provided Bristol’s water for many decades. A small spring house stood by the waterfall in the photo, right, until it was damaged by Hurricane Irene in 2011 and dismantled. With immense help from Deron Rixon of the Addison County Regional Planning Commission, Vermont Family Forests successfully applied for grant funding in 2023 through the DEC Clean Water Incentive Program to install more than 100 erosion control structures at the Seth Hill Waterworks. When we carry out the work in 2024-25, we’ll help restore the forest’s natural capacity to soak up big rainfalls. That’s good news for Lake Champlain, and it’s good news for the many upland species that depend on clear water—from spring salamanders to brook trout. Waterbars for the Waterworks 9

Landowners sometimes ask us for help in carrying out the conservation prescriptions in their UVA management plans. VFF conservation forester Ralph Tursini puts his skilled hands to work doing what we refer to as Community-based Forest Renewal (CFR). This light-on-the-land approach doesn’t require big machinery or the frozen winter conditions that are a must for minimizing soil damage when operating big machines in the forest. In this time of rapidly changing climate, such conditions are increasingly hard to come by. Moving through the forest on foot, Ralph uses a chainsaw to girdle or fell trees as needed. He uses our Organic Forest Ecosystem Conservation Checklist, with its benchmarks for minimum numbers of standing snags and downed woody debris, to guide his work. Ralph’s CFR work tends the forest with precision, in an effective, aesthetic, and ecological way. Girdled trees add standing dead habitat to the forest, and downed logs build soil health and habitat. That’s great for wildlife, and it’s great for carbon storage. And it puts a big smile on landowners’ faces. CFR work happens at a pace and extent that are more aligned with natural functions of forest systems than heavy-duty industrial logging, and it maintains and enhances the ecological bandaids for forest renewal. Community-based Forest Renewal VFF helped partner organization The Watershed Center find a solution to an ongoing issue of beavers damming the sluice holes in the gauging station at Norton Reservoir in Bristol. Below, left, Sandra Murphy constructs the frame of the beaver baffle in the Middle Barn at VFF’s Anderson Wells Farm. Below right, VFF staff work with TWC board member Ryan Sleeper (left) to install the beaver baffle. Photo, left: To directionally fell this small-diameter tree in John and Rita Elder’s family forest, Ralph made a double bore-cut through the center of the hinge, so he could drive the wedge through the hinge to create a longer lever. This allowed Ralph to fell the tree opposite its lean, to a place where its branches can protect seedlings from deer browse, and its stem—which lies across rather than down the slope—can slow, spread, and sink the flow of surface water. 10 Photo, above: VFF conservation forester Ralph Tursini girdles an aspen to increase the number of standing dead trees in this forest.

For the past few years, we’ve held all of our Game of Logging courses at VFF’s Abraham’s Knees land in Lincoln. This land is enrolled in Vermont’s Current Use (UVA) program, and as the students learn and practice the art of tree felling, they help us accomplish the conservation prescriptions of our UVA management plan. The felled trees remain in the forest, where they store carbon, slow the flow of runoff, build the soil’s organic layer, and provide habitat for a host of wild animals—from red-backed salamanders to small mammals. Rewilding Abraham’s Knees, With Help from Many Hands A Well for Wells Farm In 2023, we continued our steady improvements of the Anderson Wells Farm campus. Each step moves us closer to our vision of a vibrant meeting place for learning and soul-restoring conservation work. In 2023, we drilled a well to replace the spring-fed supply, which sometimes ran dry. The photos below capture scenes from the Wells Farm harvest. We pressed and froze more than 25 gallons of cider from the farm’s pears and apples, which will sweeten VFF events in 2024. Look up! Identifying overhead hazards is Step 1 of safe, accurate tree felling. This student and her Level 1 classmates each felled a tree at Abraham’s Knees under the watchful eye of Game of Logging instructor David Birdsall, left. The logs remained in the forest, where they augment soils and habitat. 11

Landowners & their Land—Cultivating Connections Only he who has planted a pine grove with his own hands, or built a terrace, or tried to raise a better crop of birds can appreciate how easy it is to fail; how futile it is to passively follow a recipe without understanding the mechanisms behind it. Subsidies and propaganda may evoke the farmer’s acquiescence, but only enthusiasm and affection will evoke his skill. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 Above, Bob West inventories ash trees in his forest to prioritize which to protect, preserve, and utilize. Right, Isaiah Kiley works in the Kiley family forest to release and regenerate vigorous trees. Hiring a forester to carry out forest work is sometimes a necessity for landowners, but our sense is that, if taken too far, it can drive a wedge between forest holders and forests. Getting to deeply know and fall in love with one’s forest is medicine. There’s an old Irish saying that the greatest soul restoration is that which is done on behalf of the land. We help landowners access information, tools, and skills that help them connect with and carry out the work they’d like to do in their forests. That support takes many forms—sometimes it’s a one-on-one walk in a forest. Sometimes it’s a chainsaw training class to build skills, or the loan of a tool to remove invasive shrubs. Whatever form that support takes, our aim is to cultivate connections between landowners and the lands they hold. 12

The landscape of any farm is the owner’s portrait of himself. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 Top: Lescoe Family Forest, South Starksboro Lower left: bat roost tree Peredo & Lippert Family Forest, Hinesburg Lower right: Metta Earth Family Forest, Lincoln 13

Learning to use a chainsaw safely and effectively is good for landowners and it’s good for the forest. Over the course of the Game of Logging workshop series we host, students learn to fell trees with great accuracy, to keep their saws in tiptop condition, to understand and respond to wood compression and tension, and a whole lot more. In 2023, we continued our long-standing commitment to provide top-notch chainsaw training. Taught by the outstanding instructors from Northeast Woodland Training, 30 students completed Basic Chainsaw Use & Safety for Beginners. 50 students completed Level 1 of Game of Logging training, and another 20 completed Levels 2 or 3. Vermont Family Forests sponsored three students from the Hannaford Career Center in Middlebury to complete Basic Chainsaw Use & Safety (photos below), helping build forest-based skills in the next generation of forest landowners. Skill-building in the Forest Tools for Loan At Vermont Family Forests, we practice and encourage organic forestry. That means no synthetic pesticides, vegetable-based chainsaw bar oil, forest practices that minimize invasive plant species, more large live and dead trees and more large downed logs. It means fewer roads and more stable forwarding paths. For many years, we’ve had an Extractigator on hand at our office to use when we want to pull out invasive exotic species like common buckthorn and barberry. In 2023, we purchased two more, so that we could loan them out to landowners wanting to remove invasives in their own forests. Several landowners took us up on that offer. 14

Community-based Conservation at LHCF For more than a decade, Cecilia Danks—professor at University of Vermont and one of 16 shareholders in Little Hogback Community Forest (LHCF)—has brought the students in her Community-based Conservation course to LHCF where they have a chance to put into action the ideas they’re learning in the classroom. On a beautiful afternoon in September 2023, students met with several LHCF shareholders to split wood for the Monkton Wood Bank, which provides free firewood to folks in need. They also explored the forest with David Brynn, (above), learning how stable forest access roads contribute to forest health. Below, LHCF shareholder Don Dewees (right) keeps an eye on students as they learn to operate a hydraulic wood splitter. Partnering with The Watershed Center Most people know The Watershed Center (TWC) for its beautiful 1,001-acre parcel of conserved land in the northwest corner of the town of Bristol. But TWC owns another small parcel in the village of Bristol, right across from Bristol Elementary School. The Edith Stock Community Forest, named in honor of the donor of this land, stretches in a long, narrow strip from Mountain Street high up onto Hogback Ridge. VFF has collaborated with TWC in an ongoing project to create a stable, gently sloped walking trail through the land. In 2023, a new bridge made the trail universally accessible. In addition, VFF partnered with TWC on many projects at their main land holding—known as The Lands of the Watershed Center—in projects ranging from baffling beavers to building trails. 15 Below: Bristol Elementary students have carefully lined the winding path through TWC’s Edith Stock Community Forest with hand-painted stones.

Prudence never kindled a fire in the human mind; I have no hope for conservation born of fear. The 4-H boy who becomes curious about why red pines need more acid than white is closer to conservation than he who writes a prize essay on the dangers of timber famine. –Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 Well-being and Resilience Fostering well-being and resilience—in our local community and within the ecological community of life in which we are so fortunate to live—is the fourth part of our four-part mission. When community members are nourished in body, heart, and mind, the community flourishes. Gathering together to celebrate the land, to share good food, to learn new things, to bask in beautiful music—these are some of the ways to support community resilience and to nurture a shared commitment to caring for our home place. In 2023, our annual Woodwinds in the Middle Barn event (left and below) welcomed community members to VFF’s Anderson Wells Farm in Lincoln to enjoy the beautiful harmonies of the Full Circle Recorders ensemble. 16

Each year, we offer workshops that explore hands-on application of organic forestry principles. Below, instructor Mark Krawyzck gives an introductory slideshow during VFF’s Coppicing and Pollarding course at Anderson Wells Farm. Participants then headed to VFF’s Abraham’s Knees parcel to practice coppicing techniques in the forest and finished up with wood-fired pizza back at Well Farm. Food is a big part of Vermont Family Forests gatherings. Our earth oven fired up dozens of pizzas for events in 2023, topped as often as possible with ingredients from the farm—from tomato sauce to blueberries (our favorite, must-try topping). Both sweet and hard cider pressed from Wells Farm apples quenched many a thirst. Right, staff members from the Vermont Community Foundation enjoy wood-fired pizza at Wells Farm during their annual retreat. Feeding Mind and Body 17

In the Woods with Lake Champlain Maritime Museum As he has done for more than 20 years, David Brynn headed into the forest in early 2023 with local high school students enrolled in the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) Longboats Program. The students were beginning a semester-long process of building a traditional wooden boat together, guided by master boatbuilder Nick Patch. David brought the students into the forest to learn about the forest community and about the tree species whose wood the students would be using to build their boat. Over the course of the spring, the students built a beautiful 25’ Whitehall-style four-oared wooden rowing gig, the Charlie Burchard. The boat joined the museum’s rowing fleet and made many an outing on the lake last year in LCMM’s youth and adult rowing programs. Top left: David Brynn and LCMM students at the Lands of the Watershed Center in Bristol. Lower left: LCMM students launch the Charlie Burchard in a community celebration. Below: David Brynn and LCMM students measure tree diameters. Photos courtesy Lake Champlain Maritime Museum 18

Celebrate! There’s always more work to be done. But taking time to celebrate this beautiful place we call home is an essential part of what we do. In 2023 we continued the long-standing tradition of celebrating Winter Solstice and Beltane at the Lands of the Watershed Center in Bristol. As always, music, food, and a bit of pageantry brought the gatherings to life. Below: Geoff Davis feeds the winter solstice fire. 8 Hello Springtime! Top: Carrying the maypole across the Norton Reservoir dam. Middle: Matthew Witten, Lausanne Allen, Rick Ceballos, and David Gusakov brought lively harmonies to the celebration. Bottom: Weaving ribbons in the maypole dance. Photos by Jonathan Blake Beltane 19

Vermont Family Forests Financial Report January 1 – December 31, 2023 Income ($536,746) Expenses ($439,076) General Admin $4,800 Grants $434,341 Contributed Support $20,856 Donations $12,795 Ecological Forestry $47,411 Education $16,543 Admin & Overhead $73,261 Property Stewardship $19,448 Payroll $198,745 Contracted Services $98,289 Programs $17,781 Capital Improvements $31,552 Runcie Family Forest Can a farmer afford to devote land to woods, marsh, pond, windbreaks? Those are semi-economic land uses—that is, they have utility, but they also yield non-economic benefits. Can a farmer afford to devote land to fencerows for the birds, to snag-trees for the coons and flying squirrels? Here the utility shrinks to what the chemist calls “a trace.” Can a farmer afford to devote land to fencerows for a patch of lady slippers, a remnant of prairie, or just scenery? Here the utility shrinks to zero. Yet conservation is any or all of these things. – Aldo Leopold, The Farmer as a Conservationist, 1939 20

Staff Callie Brynn, Conservation Mapping Specialist David Brynn, Executive Director and Conservation Forester Sandra Murphy, Forest Community Outreach and Rewilding Dechen Rheault, Homestead Caretaker Ralph Tursini, Conservation Forester CHEP Research Associates Jim Andrews Greg Borah Marc Lapin Peter Meyer Chris Gray Kristen Underwood Board of Directors David Brynn Jonathan Corcoran, President Caitlin Cusack Christopher Klyza, Treasurer Peg Sutlive Ali Zimmer Vermont Family Forests PO Box 254 14 School St. Suite 202A Bristol VT 05443 802-453-7728 info@familyforests.org www.familyforests.org Sally Barngrove George Bellerose Kim Butler & Chris Hopwood Allen V. Clark Nancy & Nixon Detarnowsky Don & Marty Dewees Mariana DuBrul Steve Eustis Growald Family Fund Nathan House Bill Leeson & Heather Karlson Tom Kenyon Bert Kerstetter Claire Nivola & Timothy G Kiley Partners Addison County River Watch Collaborative Addison County Regional Planning Commission Addison Independent American Endowment Foundation Coca-Cola Matching Gifts Colby Hill Fund Growald Family Fund International Business Machines Kimball Office Services, Inc. Lake Champlain Maritime Museum Lewis Creek Association Lintilhac Foundation Little Hogback Community Forest Lynne M Miller Family Trust Mount Abraham Union High School Northeast Wilderness Trust Northeast Woodland Training Scenic Valley Landscaping Shoreham Carpentry Company Silloway Computer Services The Watershed Center Town of Bristol Town of Lincoln United States Forest Service United Way of Addison County University of Vermont Vermont Community Foundation Vermont Department of Fish & Wildlife VT Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation Vermont Youth Conservation Corps Vermont Heavy Timber Company Vermont Land Trust VT Reptile & Amphibian Atlas Project Wells Mountain, LLC Gratitude Individual Donors Sketch of Lester Anderson, by Choti Judy and Kyle Kowalczyk Sarah Laird Christopher & Jean McCandless Ethan Mitchell & Susannah McCandless Shelly McSweeney & Eric Palola John McNerney Paula Nath Network for Good Barbara Otsuka Jim and Chris Runcie John Siebert Evan Stone Deep gratitude to Scott Hamshaw for his seven years on the Vermont Family Forests board of directors. We’ll miss him and his expertise in forest hydrology, water quality monitoring, conservation design, and so much more. Thank you, Scott!