Return to flip book view

Copyright 2022 The Parliament Literary Journal, ISSN 2767-2158 (print); ISSN 2767-2166 (online) is published quarterly in November, February, May, and August. All correspondence should be sent via email to parliamentlit@gmail.com. All rights are reserved by the arsts and authors. All works in the journal are conal. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author's imaginaon or are used cously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is enrely coincidental. The Parliament Literary Journal and logo design are registered trademarks. Submissions are accepted for our themed issues and contests via Submiable; details on our submission requirements can be found at our website. www.parliamentlit.com

4/5 Nikki Gonzalez 6/7 Rachel Stempel 8/9 Jill Crammond 10/11/12/13/14/15 Paul Tanner 16/17/18/19/20/21 22/23/24/25 Connor Doyle 26/27/28/29/30/31 Amy L. Bernstein 32/33/34/35 Michael Brockley 36/37/38/39 J.P. Sexton 40/41/42/43/44 45/46/47 Stephen Kingsnorth 48/49/50/51 Caitlin McKenna 52/53 /54/55 Oz Hardwick 56/57/58/59/60/61 62/63/64/65 Madari Pendas 66/67/68/69/70/71 Ranjith Sivaraman 72/73/74/75 76/77 /78 /79 Alan Bern 80/81 Bruce Robinson 82/83/84/85 Nikki Gonzalez 86/87/88/89 Michael Rogers 90/91/92/93 Jay Nunnery 94/95/96/97/98/99 Kevin Vivers 100/101/102/103 Lawdenmarc Decamora 104/105/106/107 Eddie Brophy 108/109/110/111 Lindsey Pucci 112/113 Anonymous 114/115 Natalie Kormos Artistically Inspired Contest 116/117 Jennifer Weigel 118/119 Remy Chartier (ARTIST’S WINNER) 120/121 Don Sandeen (ARTIST’S WINNER) 122/123 Alex Huynh (EDITOR’S WINNER)

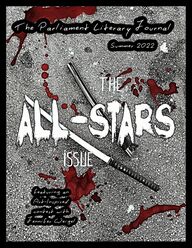

If Shit Goes Down ... This. This right here? This is the All-Stars issue of The Parliament Literary Journal. And know that if I were standing next to you at this moment, presenting you with a copy, I’d add one of those noises that goes something like “oooh wee”, all long and drawn out. And I’d be holding the issue in my hands like the pages are on fire. I’d have to help you understand, you see, that is no ordinary issue you’re embarking on. Two years ago, I started The Parliament Literary Journal on my laptop from my back porch in my little town as a desperate attempt during the first aching months of pandemic, quarantine, and isolation to connect with people. Two years in now and I’ve had the indescribable honor of meeting people from nearly every continent on our planet and sharing in their deepest, most intimate creations. To celebrate this special anniversary, I knew I wanted to spend it with THE ALL STARS -- the writers and artists who, over the past 7 issues have left a particularly indelible impact on readers and on me. I didn’t just want to highlight them in the issue as a demonstration of my gratitude and awe for their talents that they have shared with me and for the people that they are. I wanted to GIVE them the issue. No directions. No edits. The pages were theirs to express themselves in their diverse artistries as they chose. The only thematic thread that binds them together is WHO they are. They are the All-Stars. They are the SUPER-stars. They are the writers and artists whose works I have returned to again and again to cozy up with and feel a firework show of emotions -- a gamut that runs far deeper than laughter and tears. They bewilder me at times; I have certainly cringed once or twice; often I ache; and most often, I sit in stupefied awe that I have had the mad fortune to be in the orbit of these works AND the people behind them. BUT! You won’t find the pages decked out in gold stars and glitter for these All-Stars. They deserve better than gaudy triteness. Instead, I give them the apocalypse. I give them crossbows and kitana. I give them desolation. Let me explain. Ever see the show Lost from the early 2000s? Or the series that followed years later, The Walking Dead? Both shows feature survivors of disastrous or cataclysmic events. The personalities, skills, and backgrounds of each person determines their success in living. Some not only survive, but thrive. Ever since I watched these shows, I study people, especially when 4

I am traveling. While I’m waiting at my departing gate, I’ll look at the people around me and think: Who would I want to survive alongside of on an island or form an alliance with to battle the undead? Who would be kind? Who would be knowledgeable? Who would be our leader? The same (rather crude) question I ask myself at the airport, I asked in compiling this issue: If shit goes down, who do I want with me? The writers and artists on the pages that follow are my answer. And because there were no rules for this issue, I joined the All-Stars on the page with a story of my own. Not with ego. Not because I fancy myself an All-Star. But because I want to be part of the team. I want them to know that, wielding my Oxford comma, I’d do battle for them unhesitatingly. This issue, too, as all our past issues have, features an Art-Inspired Contest. The artist, Jennifer Weigel, is, of course, an All-Star, herself. Fittingly, her photography was featured in our very first issue and it’s only absolute perfection that she inspired a new batch of future All-Stars. Her photo, “Heading Home” amassed varied interpretations -- everything from ancient Greek mythology to the contemporary war on women’s reproductive rights. Three new talents are added to our Parliament family because Jennifer couldn’t decide between two and, well, rules shmules. Congratulations -- and welcome! -- to Remy Chartier, Don Sandeen, and Alex Huynh whose poems took the very risks that I admire of all the creators in this issue. So, journey through the lands ahead across these pages, where the air is still, the infrastructure buzzes, expending its last energy or stands defiant, albeit with cracks, and the people you encounter are the thrivers of it all. Thank you for the past two wonderful, empowering years. Nikki Gonzalez 5

Considerations, Predictions, & Manifestations for Chewing-Gum Jezebels 1. Your mother, a poor mouth, is waiting to hear back from you. 2. Before an apology, cradle expired milk in the groove of your tongue to leach its gonebadness, put it to better use. 3. An LCD lobotomy is only temporary but a girl can dream. 4. Body language refuses passion when you’re not a visual person. 5. Get back to your mother, ask What is the temperature of a handjob? 6. Invert the spine of a baby bear, ask Is it good? (This is as God as it gets.) 7. Discover: Mona Lisa is a lesbian. 8. I will master the on-command nosebleed. 9. Insects are no longer profitable. 10. Get back to your mother, ask Is no luxury warranted? 11. Womanhood is permanent or unbearable, not both. 12. Notice the moon is often too bright for my liking. 13. You will talk the perfect amount. 14. I’ve not an ounce of generosity in my hole-body! 15. The only real meat remaining is tuna sashimi—striated, succulent, severe. There’s a pussy joke in here somewhere. (Have you heard more pussy jokes as a woman or as a lesbian?) 16. Get back to your mother, say I offered my womb to the highest bidder. 17. Notice the moon is often too bright for my liking. 18. Get back to your mother, say Milankovitch cycles have made me awful lonely. 19. Blossoms are now contagious—Rejoice! (Better late than never, says the birth control manufacturer.) 20. Be mildly academic, leave enough room for hysterics. 21. I am waiting for the last Beatle to die so I can win my mother back. 6

Rachel Stempel is a queer Ukrainian-Jewish poet and PhD student in English at SUNY-Binghamton. They are the author of the chapbooks Interiors (Foundlings Press), BEFORE THE DESIRE TO EAT (Finishing Line Press) and Dear Abbey (Bottlecap Press). They live, laugh, love in New York with their rabbit, Diego. 7

In Praise of Packing Lunchboxes It’s very difficult to plan something if your day is constantly interrupted by dead things. The cat lays two dead mice at your feet, one after the other dropping from her red-tinged mouth and you stop packing the lunch boxes. You marvel at the irony: two dead mice, two hungry children. Somewhere in this house are two mothers with two children depending on them. You think about taking the mouse mother out to lunch. Are all children furred and tiny? you will ask her. Are all children silent and maimed? Depending on the day, you either put the mice in a Ziploc, draw a heart on the bag and feel proud that there’s something new to feed the children, or you focus on the task at hand. If you are a decent mother, you smile benevolently, teeth wide, white, and showing, good humor not quite reaching your eyes. You say, Good kitty. Never change. You never say, They had it coming. You never curse the cat’s ambition. Out of the corner of your eye you see a shadow. You dial your dead ex-husband, but the call goes to voice mail. Not mourning, but you’d like to know what he did with dead mice. At some point, you remember about lunch. As usual, the sticky note on your cupboard door has failed you: Don’t forget to feed them. No one tells you how to mourn. You ask your mother. She says, Try baking a casserole. You ask your children. They say, What’s for dinner? You’re still not sure if your dead ex-husband is dead or a divorcee. Isn’t that a nice word? you ask the cat. Doesn’t it sound like a fancy name? You read papers about division of assets, equitable distribution. You take out the hedge trimmers he left behind, put on the blue flannel shirt he forgot on the back of the bathroom door and measure as much of the house as you can with a tape measure. Should I draw a line with chalk? you ask the cat, then walk back inside to search for a chainsaw. It's still Monday morning, you shout at the mailman. The children have boarded the bus without their crustless peanut butter and jellies, without their clementines swaddled inside seasonally themed napkins and love notes. I’m coming, you shout to the cat. Tell the children. The shadow you saw earlier shakes its head, reaches out and shoves you out the door. Is it any surprise when you slip on the mess of a fledgling that has fallen from its nest inside your porch light? Any surprise that you are overjoyed at the prospect of erasing the death, continued 8

resurrecting the lunch? Not the death of a mother, but the demise of a life well-intentioned. No one can see the man floating alongside you as you push your cart through the produce aisle, fondle the avocados, wonder how many germs you’ve left, how many you’ve picked up. Ghosts don’t worry about germs, and they don’t have a sense of personal space. Your dead ex-husband is in your personal space, and all you can say, over and over as you wait in the deli line behind a gray-haired woman with her slip showing, is, Nothing has changed. Nothing has changed. You got that right, you think you hear her say, as she orders the last pound of American cheese in the deli case. Death makes for a poor bedfellow. Your memories are cadavers. Your first date after becoming single is a noon-time disaster of dead air, dead chicken, and dead mother-in-law jokes. He’s a nice guy, as morticians go, but his jokes can’t raise a sleepwalker from the dead, and he smells like formaldehyde. You have asked the waiter for three new knives. Each one is duller than the next, and it’s not until you are finally carving your baked breast that you remember the children. They are still at school, and you still haven’t delivered their lunches. 9 Jill Crammond’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in Limp Wrist, Tinderbox Poetry, Mom Egg Review, Pidgeonholes, Unbroken Journal, Mother Mary Come to Me Anthology, Fiolet & Wing: An Anthology of Domestic Fabulist Poetry, and others. Her poetry has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and her chapbook, Handbook for Unwell Mothers, is forthcoming in May 2023 from Finishing Line Press. She lives in upstate NY where she teaches art and preK at a nature-based school.

fuck the working class trust me, I’m one of them and I’m telling you: fuck us. as a shopworker I have been subservient to my own all of my adult life and all they’ve ever done is push me around and try to get me fired. even during the pandemic we “key workers” didn’t get any respect: in fact, our neighbours gave us even more abuse while they infected us. a shop worker in this country will not go one shift without being threatened insulted and accused by their fellow class brethren under the narcissistic opportunism of “customer service” continued 10

and then they have the deluded gall to complain about the lack of staff and self-service machines? about unemployment and lack of jobs? about mental health and unjust hierarchies without any irony? what miserable self-destructive cannibals they are, the fucking working class: they get the faces and the children and the governments they deserve but I don’t deserve any of them so I say fuck ‘em: it is after all what they and therefore I want. 11

new job … but it’s the same old night shift. the same old staff canteen, with the same old monobrowed meatheads, scratching and farting in the corner. you feel their piggy eyes on you as you sit down alone in the corner opposite … then some gangly lad comes in. he looks around, nervous. until he clocks you, that is. and then he smiles – a little too wide – and heads straight for you. great. the same old work creep latching onto you as always. he takes a seat next to you. not opposite, no – next to you, so that your thighs are touching. your thighs are touching the whole time he’s sitting there and he just sits there the whole time, not saying anything, just sniffing and humming while your thighs touch. and you’re going mad, you’re about to turn around and stick your thumb in his eye, gouge it out and spit in the hole, you feel so violated – suddenly there’s all this noise, desks bumping and chairs scraping, everyone’s getting up and heading out. the shift must be starting. even gangly lad deserts you. so you’re at the back of the throng, following all those shapeless man buttocks out onto the shop floor, when the meathead in front, he shuts the door and turns to you, trapping you in. it’s just you and him now, in the same old staff canteen of the new job. that gimp you were sitting with, he says. you don’t wanna be associating with him. I know I don’t, you agree. oh do you, yeah? he mocks you. let me tell you something about your little gimp mate. he’s not my – he paid his sister to do a shit on his chest. you just look at him a minute … he paid his sister, you repeat, to do a – continued 12

a shit on his chest, yeah, the meathead nods. that’s right. and how do you know this? she told me. she told you? she happily confided in you that she performs incestuous scat for money? yeah! his fists rest on his hips when he boasts: been banging her, haven’t I? you’re banging her. yeah! you’re banging someone who shits on their brother for money? I think I’d rather shag that gangly lad, you conclude. and you walk past him but you don’t go onto the shop floor, o no, you don’t even clock on: you grab your coat off the peg, go through the warehouse, duck under the shutters, walk diagonally through the delivery loading bays and across the car park until you reach a wired fence. you duck through a hole in that, and find yourself in some back lane, the same old back lane these supermarkets always have behind them. and you’re walking … and there’s a rumble … and behind the littered bushes to your right, you see the roof of a train rattle by. that’s tantamount to reassuring, for if the train’s just passing through … why can’t you? 13

A Peek Into the Diary of Tanner: Excerpts boomer bitch who lectured me for 6 minutes about the plastic bag charge: think of all you achieved today, giving your big speech to a minimum wage taxpayer who can’t even answer back to you, let alone the government who enforce the bag charge. think of all you achieved today when you sit in traffic, huffing and puffing. think of all you achieved today when you’re blubbing over cold dinners while your piece of shit husband is still at the office, getting violently sodomised over the desk by his barely legal intern. think of all you achieved today when you wake up at 3 a.m. in an empty bed, so alone and bored that you put a bread knife to your fat neck and silence all the rage between your ears with awkward slashes that take a fair few jagged wet minutes. think of all you achieved today, and all you achieved today can be your final thought: my face, looking at you across the shop counter, bored. 14

that customer with his hands down his pants scratches at his balls with almost as much venom as the security guard does, but not nearly as venomously as my floor supervisor does his. And I never did mop up that puke in aisle 5: by the time I got to it, it’d already dried up, like a comparatively flat brown pizza: I just kicked it under the shelves and went. Tanner was born tomorrow. He's been earning minimum wage, and writing about it, for too long. His cat knows your sins. Uh huh. 15

suspension 16

same day service 17

honk if you heart america 18

Advertise Here! 19

BY TALI MINK BAR 20

BLM 21

Don 22

Elle 23

SPT FEE RISE 24

for lease 25 Connor Doyle is a photographer and filmmaker based in the Chicagoland area. Using a number of analog film formats, Doyle’s work focuses on the idiosyncratic details of daily life in Northern Illinois, specifically his native Wheaton, IL. Though often trivial, his subjects capture the formal beauty and potency of these everyday sites, urging his viewers to reflect on the significance of their lived experiences. Connor’s work has been published in the High Shelf Press, the Hole In The Head Review, Humana Obscura, and the Burningword Literary Journal. You can visit his website at https://connordoylephotographyfilmmaker.cargo.site/

Aborning Meaning—look at how long it took me to grow this body from a primordial cellular legend, all striving and push, desperate to be first out of the starter gate, bursting slursh, a chaos of slicked flesh, sloughing off the amniotic mess in a rage to get on with things: oh but what a disappointing mess, the world, dry land, dry bones crackling against pavement; if only mitosis had kept me better informed, I would insist on emerging as a salamander, an axolotl, a starfish, regrowing limbs at will, endowed with gifts suited to rebuffing wounds, disappointments, the coming slaughter; meaning—look how long it took me to reject this body and crawl back into the unlit womb, regressing until it became nothing (a bell jar). 26

Nocturnal Cosmos Ambassadors from the Andromeda Galaxy visit on Tuesdays at 3:33 a.m. my head lifts from Pillow Earth, nods to my sleep-disrupting friends cruising by on their way to somewhere, anywhere, everywhere others follow from the Milky Way, to tease or torture, dropping by on Saturdays at 2:22 a.m. hormonal/diurnal rhythms cannot account for cosmically precise disruptions. I am visited from the beyond, my flesh pelted in the wee hours by hadrons, photons, leptons. 27

Kike He says the word so casually conversationally in conversation with others he may as well say ‘water’ or ‘bread,’ it’s that easy I am fourteen hearing ‘kike’ spoken out loud by an adult I barely know someone has warned me—who?— someone who wants to shield me against incoming mortar fire who suggests I wear a flak jacket or maybe just learn to duck that’s why they teach me the word, to be on the look-out I’m standing there when he says it, not six feet away In that moment, I am passing, I am the one passing as ordinary white not jew white because he’s not saying it at me, I’m included in the general sentiment, painted with his filthy brush like everyone around me continued 28

still, a taste of— this— but only a taste as my body vibrates with fear and anger and shame just this once because the first time didn’t really count: birthday parties to which I was not invited being a little jewish girl in a town of old new england wasps. I don’t find out until years later. 29

Going Fourth/Bad American Karma You are naked but for the spangle-flecked blanket, all tiddlywinks, stars, and sparkles, enfolding you like a seashell’s whorl, a superhero’s cape, an all-purpose excuse for avoiding entanglements that might pierce your flesh or leave even the slightest, faintest trace of purpose or pity or something uncomfortably in between— a bruise of some kind. Blanketed, you stride down the avenue like Lady Godiva without her horse, the streaky fabric streaming behind you like a flowing river of golden locks. Clever how your tender flesh, all hidden and be-layered, denies the witnesses beholding your passage the satisfaction their gnawing hunger demands. You wish not to be followed or even understood, but to get so lost, the blanket itself grows weary, its grip loosens, or your grip loosens: impossible to know for sure. The locomoting blanket loses steam and grinds to a flat halt on the pavement, or the grass, or the stony shore, wherever and whenever you part ways. The spangled blanket made by fingers the size of a buttercup’s petals: More hungry witnesses denied a satisfaction of one sort or another. Let some stray waif or fairytale-besotted oaf take up the blanket, stained with your exploits and half-veiled intentions. Let them stage a new parade, perhaps flesh-baring this time, the blanket more prop than cover. You will paddle away toward a cool, clear, baptism, a ritual purification to wash off the last of the spangled blanket’s filthy microbes. You get away with everything, yet again. 30

Amy L. Bernstein writes stories, essays, and poems that let readers feel while making them think. Her novels include The Potrero Complex, The Nighthawkers, Dreams of Song Times, and Fran, The Second Time Around. Amy is an award-winning journalist, speechwriter, playwright, and certified nonfiction book coach. When not glued to a screen, she loves listening to jazz and classical music, drinking wine with friends, and exploring Baltimore’s glorious neighborhoods, which inspire her writing. Learn more at www.amywrites.live. 31

The Widowmaker at Owl Light A Bards on the Run Poem Aloha Shirt Man finishes off a poem about a woman who collects roadkill skulls. The fragile craniums of nightbirds. The souls of possums. He is typing poems for hire on a gunmetal-gray Underwood in an abandoned warehouse that hosts a twentieth century speakeasy. Two highpockets in zoot suits escorting even taller women in Prohibition dresses pass by as Aloha pecks out the first line for a waitress named after a state famous for its peaches. He hums “Sweet Georgia Brown” while imagining himself a virtuoso accordion player. Although he thinks Squeezebox might be the bee’s knees as a juke joint moniker, he autographs his poems The Widowmaker. Claims he can “erase” unwanted spouses with the Underwood backspace key. At the bar, Stilts and Goliath argue over how to jury-rig fuse boxes into robots. Ignoring their sequined Shebas who tap their stiletto-heeled feet to “A Little Party Never Killed Nobody.” Two keystrokes later, the goons vanish, replaced by the ghosts of barkeeps eager for a last-call hustle. A crackerjack pick-up line from beyond the pale. The widows celebrate their windfall with a devil-may-care jitterbug to the dance floor. At his typewriter, Aloha tinkers with a poem for an artist who crafts sculptures from dryer lint and the gum she scrapes from the bottom of her shoes. The ghosts of moonshine runners mingle among the revelers, picking pockets and switching key chains. Having worn away the arrow on another backspace key, Aloha downs a shot of Heaven’s Door whiskey, an appreciative bump from another newly-minted widow. 32

Grift Pocket Memoir from Nightmare Alley As you approach the showman’s trailer, a ferris wheel looms over the carny stalls like a B-movie behemasaur slavering over metropolitan prey. The man who greets you from behind a disarrayed desk once kidnapped a mute woman from a camp of rejected wives. But the showman does not know you turned the hanged-man card upside down. Nor that you once fleeced a judge and trusted a woman who wore scarlet lipstick like a bludgeon. A matricidal fetus stares at you from its thalidomide jar among the carny’s collection of pinhead skulls and hinterland heirlooms. The showman senses the dead fathers in your wonderland eyes. And suspects you were born to be the shadow that lingers in midway spook shows. “Enoch,” you say, remembering the dead child’s name, and draw your jacket around your sunken chest, the colorless coat you looted from a sleeping pigman after the hobos drove you away from their circle of Jake-leg hootch. As the carnival boss settles a thimble of freak-show gin into your trembling hands, he offers a gig in a geek cage. With a pallet to sleep on under a miscellaneous tent among blue moonshine and chicken crates. This is how the rest of your life begins. 33

Reporting to Mars from the Country of Side Eyes, Tenderloins, and Skeleton Keys Twenty-nine percent of the naked apes identify blue as their favorite color. Green is their second choice, followed by red and purple. The plural of blue changes a color into a form of music that celebrates coming up short and standing on the outside while looking in through a window at something that’s always out of reach. A man has the blues when the woman he woos drops him like a hot potato for a different man who keeps more portraits of presidents in his wallet. The blues visit a woman when she wants some sugar in her bowl. When she wants a Mercedes Benz while she’s driving a rust-bucket El Camino. A potato is a root vegetable that can be baked after its eyes have been peeled off. People who catch hot potatoes toss them to someone else like they’re throwing away bad luck. Many years ago, the naked apes chose their presidents by voting for the tallest, oldest white man who promised to put a chicken in every pot. Some of those candidates wore white wigs. Some of them took pride in knowing nothing. Now the naked apes trade pictures of those presidents for cheeseburgers and blue lipstick and patio furniture. Sugar grows on large swaths of land, and some naked apes sprinkle sugar on the cereals they eat for breakfast in the crockery they call bowls. The youngest naked apes insist on eating Fruit Loops and Trix. Cereals that are red and green and blue. Only three out of a hundred naked apes confess their favorite music is the blues. 34

Sunday Brunch at Cafe Patachou The waitress serves me a mocha latte with my Omelette You Can’t Refuse. She tells me my drink was made with oat milk while I debate the merits of dishes named after movie lines. Some like it hot. Gentlemen prefer blondes. Like the old steel worker I am, I wonder how oats are milked. How the improbable rises to plate du jour. The barista swirled a heart on top of my beverage. And the wheat toast I ordered as a side is almost as delicious as a French pastry. When I sip my drink, I taste a hint of mocha and the creamy flavor of an exotic milk. Later I walk past the stalls and kiosks of a neighborhood art fair, where I admire black-and-white photographs of an Underwood typewriter with a sheet of paper rolled halfway up the scroll. The only word in any of the mounted photos is “Love.” Followed by a comma, a pause. The machine of a vintage that might have been used by Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum if either had played Ernest Hemingway or Dashiell Hammett. The waitress spoke with a Caribbean lilt. And wore dreamcatcher earrings and a Killing Eve t-shirt. I’m lost in Indianapolis, far away from the gyro deli where I once wrote a poem about a phone haunted by the calls of someone else’s jilted lovers. I’ve arrived at my destination without any memories of my journey. Where I search for the answers to questions I no longer understand. Michael Brockley is a retired school psychologist who lives in Muncie, Indiana where he needs to have a tree cut down so his pollinator garden can get more sun. His poems have appeared in Hobo Camp Review and Wild Word. Poems are forthcoming in Book of Matches and Unbroken. 35

Slow Drip Sometimes it feels as if I am hanging by a thread held together by a paperclip. Life seems little more than a bed I have rented for the night. That’s not to say I am ready to release my grip. My fingernails dig in deep. I have still more words at the cusp of a drip on to a page for one to ingest. 36

Hacked Apart I wish life came with an expiration date the kind you find on a yogurt lid. If it did, we could have shaken hands and buried the hatchet in time before it hacked us apart. What is it they say? Pride comes before a fall. That was me to a “T” Not that you were much better but then your letter opened my eyes. An apology was the last thing I expected as was the invisible ink. 37

The Scent of You I gulped down your scent Like fever-water, 38

39 J.P. Sexton grew up in the most northerly point of Ireland - the Inishowen Peninsula. He writes about his native homeland, people and places around the world where he has lived and worked and basically all kinds of random thoughts. He has been published in The Irish Times, The Garda Review Magazine and The Connaught Tribune. In 2016 his memoir; "The Big Yank - Memoir of a Boy Growing Up Irish," was published on Amazon as was "Four Green Fields..." in 2018. He is currently editing a sequel to his memoir titled Drawn to Danger (working title).

Here’s canvas stretcher; type for art if studio - or battle field, where medic’s bear as their first aid. A hoop spread cross, rough risen ground - dust, where buried life, to dust, not engraved pristine bleached stone mark, serried parade of gravestone ranks laid Commonwealth Commission grass. The irony, this private site misspells surname of the deceased, whilst names as worth his sacrifice, Frank, soldier Kingsnorth, far off land. To Be Frank, Private 40

Liminal What was the moment you arrived, when you, the child, could be shown off, and they seemed proud to name you theirs? That liminal, transition point, when you know more than they, for sure, and they know that, with awe, inside, not adolescent in pretence; for it’s your ground, they visitors, not entertainers, entertained. It took no craft, but punt and pole, a bridge of sighs to navigate, a competence few strangers find, and shirt, bought Delhi, on my back. 41

She wants to leave, too far the home, while health permits the timely move, beside our daughter, nurtured boys - twice monthly visits, not suffice. She younger, caring has a price, and as my wife I promised her. Our cottage dream - for ease I put it in her name - with ceiling wood and open fire, the quarried stone and furnishing, tattered, old, patina time of memories, most good, some pain. Compact, but yet three double rooms, grandchildren gathered in their prime. The garden, triangle of green, dug compost to compose the soil, wisteria, clematis climb, over fawn stone, half-timbered front, and shrubs with berry overload, red wax and shine, some purple pearls, live tadpole pond with kingcup whorls, like Devon lanes, my naïve youth, plucked primroses of teenage days. My view of dreams, dun bracken, heather on the hill, the hamlet hanging from its side, red brick where workmen mined the lead, and buzzards wheeling out their turf, no lens, zoom ten, such common treat. And in the village, end of road, first doctor I could trust and talk. My Scattered Place 42

A near community of faith, an open table of diverse, where strangers welcomed in as friends, the place to be, belong, believe, where this old pilgrim thought to rest. She wants to leave, downsize my term, and as my wife I promised her. Maybe while still my mind remains, this earth yet be my scattered place. 43

Without my specs, I saw a cheese, well-ripened, past its sell-by date, hard cheddar mixed with herbal flakes, goat gouda stuffed with fenugreek - but study clarified the stitch in plastic, not a leather seat. That sets the age - assume not staged, conglomerate, synthetic mulch, but stratified, a grating rind, absorbent tissue for the moss, wherever dip or needle hole. Unpromising to propagate, like buddleia in bomb site crack, yet here it is on moulded shape, a host for green and creeping things. Though saddle-sore, I don’t think staged - it takes me back to Cambridge days, drop handlebars - no sturmey gears - just pedal power and lecture notes, in woven basket strapped to rear, and padlocked to a college rail or thrown, if late, tutorial. Indeed, here framed, it might be mine, bike lost, occasion such as this, poor time-keeping, that machine thrust to ground for theft outside the school - that session, thief in paradise; the life expectancy of wheels a resurrection bicycle, in tandem, saprophytic style? Re-Incarnation 44

45

I carried a Pisa pile towards the door desk, greyish tinge. The bright street frontage, poster glow felt-tip scrawl announced, not Alexandria, but fire damaged stock for sale. High School me, taken self to town, found this people-free paradise; miser pocket-money in pig-skin purse and upstairs warehouse, rickets stairs. Cubic capacity, volume of books, as if building razed, scarred library, leaving untidy, uneven brick foundation course which might totter, crumble, bravely stand, though interleaved mortar might fall about. Column or torus, cheapest heaps, towers, footstools, pilae stacks, with floor before another plinth, classic publishers fading pink, a hypocaust for everyman, Dutton, Dent and Routledge, English bricks in global walls. Picking through rough rubble site, bombsite pages still bound, intact, I sifted authors, faint pencil fly just a dime/tanner, though ‘just’ is mine. Juvenile choices from printer’s block tray, lines with words, incunabulae of literature, devoured by hungry, on every page of history, Taking Stock A portrait of the arst as a young man, but with the seeds of blooms sll on display… continued 46

appetite never satisfied. Short boy, still teen, conservative in style, probably in jacket, tie, like tight-rope walker stretched balance reaching towards cash register. I waited while she totted total shillings spent. Seeing selection for my shelves, she posed was I a teaching man? Now feel six feet tall I chuckled, denied, but volumes carried, swelled with pride, a glow recalling embers laid around these for basement prices paid. If she could read those light lead-marks, eye-sight good in that dinge site, more confident my bus stop stride. Though fifty on, two yards from here, those tomes look grand; yet still unread. First published by Literary Yard Stephen Kingsnorth (Cambridge M.A., English & Religious Studies), retired to Wales from ministry in the Methodist Church due to Parkinson’s Disease, has had pieces published by on-line poetry sites, printed journals and anthologies, including The Parliament Literary Journal. His blog is at https://poetrykingsnorth.wordpress.com/ 47

Wedding Ring Hairball I want you to ask me to marry you. Not because I want you to ask me to marry you, though if I were to marry at all, I’d like it to be you. But we both know you’re not the marrying type and I don’t mind either way. I just want you to want to ask to marry me. I want to feel your heartbeat in my coronary and have your signature on my hospital chart. I want your name next to mine in my obituary and I’d like it if someday we were buried next to one another. What I’m saying is that if we were two women buried in Heptonstall cemetery who died 100 years ago our tombstone would read ‘cait and her dear friend’ because you are my dearest friend. What I’m saying is that I think when they cut me open they'll find your hairs growing on the inside of my chest and that’s why I got a little itchy when you’d been away for too long, and each nervous butterfly was a hairball growing in size waiting to be coughed up when you closed your eyes and maybe the way I can’t be away from you for more than a few days is the strands wrapping around my intestines trying to tie me to you, making me sick as you draw away. So I’ll walk you back in, I’ll twirl you through my door, down my stairs, into my bed. What I’m saying is that the soles of my feet are blistered from treading barefoot in your footsteps, hoping to go through life beside you without disturbing your peace. What I’m saying is that the calluses on my hand match the calluses on yours and I want you to marry me - Maybe or maybe I just want you to never leave. 48

Sea Foam - Sea Tomb Sea/ sea foam/ cradle/ tomb/ cut glass/ last chance/ slow dance/ shadow work/ cut the tie/ cut the cord/ learning knots/ thread/ threadbare/ ribbon hair/ shibari/ untie me/ rope/ burn/ ropeburn/ strangle/ stagnant water/ anchor/ cage/ stranglehold/ stronger/ slave/ hold/ held/ welder/ would you Hold her Be stronger Burn for her Strangle in her hold Tie yourself up in knots to fuck and be fucked up Would you unravel to cover her in a shawl of your well wishes - net of kisses - to become a threadbare gent Would you mind if she had to cut the cord 49

Hush If you’ve never seen skin bubble and blood begin to boil you’ve never been told to hush. The way the black slowly creeps in, replacing the scarlet as it crescendos into burgundy hues, and the ooze that accompanies it. The crackle and the pop not from anger but release. I’ve been told since I was young I am too much, too loud, too sensive. My mother told me being around me was like walking on eggshells. I spent the next seven years scared to be enough, silencing the tremors that threatened to erupt from the soles of my feet. I shrunk down and had to coax the lullaby from my voice box just to sleep soundly at night. Allowing my scars to fade and heels to plant, every day I allow my volume to climb is a new summit. Every me I split my ribs open and unfurl my lungs like stage curtains opening the performance, I brace for the crics. It was never my mother’s fault for being afraid the world would not be big enough continued 50

to handle the velocity of my trajectory. Or that I might one day reduce those I love to ash in my volcanic, panic zone. She could hear the hiss, see the rising smoke I slowly emit when she got too close. I know some days I must shh. I can somemes be too much. Caitlin Mckenna is a queer, socialist, vegan poet from Leeds, UK. After completing her Master's in Creative Writing Caitlin has been working as a writer across the North while performing at events in Leeds, getting published in various journals from Fragmented Voices to Grim and Gilded, and completing her debut chapbook, coming August 2022. With a deeply confessional style and an unapologetically confrontational voice, Caitlin’s poetry covers a wide variety of topics including mental health, sexual violence, and sexuality. 51

Butterflies Everywhere 52

Ever After Every time we meet it’s the same story or, at least, a different story with the same inflections. A dull day at work: there’s the pause. A bruise-black sky and the streets rippling like ripped silk: there’s the quizzical modulation. We have painted our windows 70s white and rammed our pockets with ice cubes to stave off the imminent heat, while pop songs and graffiti remind us that the openings for living our best lives are narrowing with each intake of breath. Once upon a time, you explain to the tune of a piano in that Casablanca bar, there were eleven boys cursed into swans. Mist gathers to the cough and sputter of a light aircraft and sighing strings, and I tell you about my mother’s mother, her hair a shining spider’s web, her apron overflowing with magpies beyond number. Your hair brushes my cheek like soft rain. Every time we meet it’s the same story, though the words are always different. 53

The room is how I like it, with its polished chrome stools and tasteful LED glow. At one end, a vintage arcade game synthesises explosions and emotions in an ecstasy of colours. At the other, the chequered floor falls away to the sea a hundred feet below. Rapt in the game, the boy who never grew up, sloppy in hand-me-downs, batters buttons as if he knows his life depends on it, shaking tiny universes in and out of being. His schoolwork will never be done, and he’ll be up all night, polishing chrome, populating the worlds he’s fashioned from his pent-up rage, and pining on the edge of the abyss for a life more like sitcoms or sci-fi novellas. And lest I be misunderstood, the boy is not me and his worlds are his own, just as my words are my own, polished like chrome and falling away at the edge of a room that resembles a vintage arcade game. I don’t know how many lives I have left, but I hope to spend at least one with the woman who bumbles in with a basket of books, flush-faced, in an ecstasy of colours. Retro 54

Oz Hardwick is a European poet, photographer, occasional musician, and accidental academic, whose work has been widely published in international journals and anthologies. At time of writing, his most recent publicstions are the prose poetry chapbook Reports Come In (Hedgehog, 2022), the co-edited (with Anne Caldwell) book Prose Poetry in Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2022), the album Paradox Paradigm with interdimensional space rock band Space Druids, and a magazine interview with rock legend Arthur Brown. Oz is Professor of Creative Writing at Leeds Trinity University and his cat is called Louis. www.ozhardwick.co.uk 55

Testify Humberto sprinted across the middle school’s parking lot. He was in such a hurry he had forgotten to lock the Ford’s doors and grab his wallet. His gait was long and light. It surprised him how sprightly his forty-one-year-old body could still move. For a brief second, he felt exhilarated to allow his body such freedom of movement. Humberto felt unbound, until he had to throttle his speed and enter the long, cool corridor of offices in the administration building, which separated from the main row of classrooms. They hadn’t told him much on the phone. It was hard to hear the vice principal clearly in the shop. An old Tercel was getting lifted onto the stack for a rotation and the boys were arguing again about Obama—the car had a large HOPE sticker on the rear which had promoted the rantings and debate. The mechanics would debate anything. They took exquisite pleasure in forming their arguments and counterpoints. And when all else failed to change their opponent’s mind, they elegantly told them to go fuck themselves. Humberto had left right before the eat shit and die began. Was Yessenia okay? He wondered if someone had hurt his daughter. He couldn’t take another loss. They couldn’t. The secretary nodded while he explained the call and who he was. She clicked away in her black pumps to see if the vice principal was ready. The woman was attractive with her mousy features and curious brown eyes. Humberto felt a shock of guilt for admiring this woman. After everything, he still wore his wedding band. When the secretary returned to the front desk, she waved for him to follow. She led him to a modest office in the back. Before departing, she whispered, “sorry about your wife.” So she had heard, Humberto thought. They discussed gossip more at those PTA meetings than student performance. “Thanks,” he said and gave a polite, toothless grin. He still didn’t know how to react, but she seemed to mean well, and he liked looking at her. Her freckles made him think of lazy summer days. In the office, there were diplomas and certificates all over the walls. There was a large mahogany bookshelf that ran along the length of the wall. Humberto thought all these books were for show. If he asked, he’d bet the VP didn’t even like to read. 56

Yessenia was in the chair across from the Vice Principal, Mr. O’Hare. Humberto took the seat next to his daughter and scanned her face for signs of damage. She looked so much like Mirta it was hard for him to not feel an immediate lump in his throat whenever he looked at her. It had been thirteen months since Mirta’s death, and yet the pain felt ceaseless. Humberto thoroughly believed it’d never end. “What’s going on?” Humberto asked. “I got here as fast as I could.” Humberto was still in his mechanic jumper. There were oil stains on his chest and sleeves. Although he had become inured to the shop smells, he imagined he probably stunk heavily of gasoline and sweat. He felt out of place, especially compared to Mr. O’Hare who wore a navy gabardine suit with a checkered pocket square and gold horn-rimmed glasses. This was the type of man who knew which fork to use at a fancy restaurant. Mr. O’Hare cleared his throat. “I wish we were meeting under happier circumstances, Mr. Sandoval, but your daughter was caught self-harming. We also found this in her bag.” He delicately held up a box cutter. Had she pilfered it from Humberto’s toolbox? What was Yessenia doing with it? What did self-harm really mean? Humberto’s English had barely improved since moving to the states. Everyone at the shop spoke Spanish, which didn’t incentivize Humberto to practice his English. With the Gringo customers Humberto got his point cross with elaborate hand-pointing and gesturing. He wished for Mirta. She had studied English at La Universidad de la Habana. “Your daughter set off the entry metal detector this morning. We found this on her person.” Mr. O’Hare daintily put a boxcutter on his desk. Humberto recognized it as the boxcutter he kept in the catch-all for packages. He wondered if he could ask for it back but didn’t. “Her intention may have been to self-harm, but she hasn’t been the most cooperative. She’s going to receive two-weeks of outdoor suspension.” “Two weeks?” Humberto wanted to ask more questions, have the man explain, but nothing came out of his mouth. Much of his mental bandwidth was being used to translate the English to Spanish and then his responses from Spanish to English. It felt like trying to change a tire on a moving vehicle. Humberto said, defeatedly, “Okay.” As Humberto and Yessenia walked out of the office Mr. O’Hare said, “Also I’m sorry for your loss. If it were my wife…” his voice dimmed, perhaps uncertain whether to finish his thought. Humberto 57

had learned that the other side of sympathy was a self-centered gratitude at having been spared a similar fate. “Take care. Thank you for coming in.” On the ride back home, Humberto kept looking at Yessenia. Would the universe take from him again? What was wrong with the girl? Why would she hurt herself? Had he misunderstood Mr. O’Hare? Was she trying to harm her classmates or herself? The moody fourteen-year-old girl next to him picking at her nails seemed so different from the pig-tailed munchkin he used to take to Amelia Earhart Park who’d beg to go higher on the swing. “More, Papi!” She’d demand, smiling her gap-toothed smile. “Pa’riba!” At a red light, he cleared his throat. He needed to know what was going on with his daughter. “Show me.” “Show you what?” She leaned away from him. “We’re on the road, Dad.” Dad? She had stopped calling him Papi when she started at that Our Lady of Lourdes, which Mirta had insisted would be better than the assigned public high school in Hialeah. He hated the sound of the word “dad.” It was more like a chewing noise, empty, incomplete, hard on both ends. When she said it in private, Humberto wondered who it was for? None of her little Gringo friends were listening, which meant something in her really had changed. This was who she was now. Surely the girl that said Papi and insisted on spending every moment outside would have never self-harmed, surely. But that was a girl who still had a mother, a counterpoint to Humberto. “Basta. Lift the sleeve. Are you trying to kill yourself?” Yessenia pulled at one of her red slapbands. “No,” she said weakly. “You can’t make me.” The light was still red. Humberto leaned over the center console and grabbed her wrist. With his other free hand, he rolled down the black cotton fabric of The Ramons jacket she always wore over her school uniform. “Dios santo. What is this?” A Kia behind them honked. The light had changed, and Humberto released her. There were rows of cuts down her arm like tally marks. The scars and scabs were deep, and he took this to mean she had been cutting for a while. Humberto kept his eyes forward on Le Jeune Road, but what he had seen lingered. He could see the wounds in front of him as if it were an afterimage effect. They stopped at the light on 42nd and NW 6th Street, near the OceanBank cinema. Humberto 58

thought of Mirta’s body in the hospital after she’d been T-boned by the driver. The bones in her legs had skewered through her thighs, her chin had been partially collapsed, and her front teeth had shattered—she had once been so proud of her smile. She’d find any reason to smile, whether it was for a Zebra Longwing that had landed on her shoulder or because the clouds that day looked like a banana rat. Bodies change. Now, buried in the ground, he imagined her body was still changing. “Why do you do that?” He demanded. His gaze bounced between the road and his daughter. Yessenia pulled her legs to her chest. She wiped the sides of her eyes. Humberto asked again, louder. She cried into her sleeve. “I miss her.” He scoffed. He missed her as well. But he wasn’t causing a scene or hurting himself. He couldn’t understand this behavior. If you missed someone, you’d honor them, Humberto thought. You’d do everything in your power to make them proud. Mirta jumped through a million hoops to get her into Lourdes, Yessenia knew that, and still let herself be suspended. Malagradecida. “So do I. But you don’t see me acting like a crazy person. ¿Qué te pasa? “I don’t know,” she whimpered. They were almost home. Humberto thought of calling the shop owner to see if he could get an extra two hours before they closed or come in earlier tomorrow. He was already calculating how much his next paycheck would be and if it’d be enough to cover rent, or if he’d need to get another payday loan. Chewy, one of the older mechanics, was always looking to leave early to go fishing on the Rickenbacker. Maybe he’d let Humberto cover his closing shift. Yessenia’s head was between her legs while she cried. The noise of his daughter weeping should have made Humberto feel sympathy, or pity, for his girl, but instead he felt rage at himself (for raising such a weakling) and at her (for not better managing her emotions). Everyone was upset by what happened to Mirta. Everyone. “Stop crying,” he said, pulling into the duplex’s parking lot. “How are you ever going to find a husband acting like this?” She grabbed her Jansport from the backseat with the white Tamagotchi her mother had bought her. Humberto didn’t get out of the car. “Make lunch. I have to go and make up the hours I lost because of you.” He could hear his own cruelty. It was almost as though he was observing himself but couldn’t stop. There was something addictive about this behavior. A power he had nowhere else in his life. She was the only one he could take his rage out on. “And don’t kill yourself while I’m gone. 59

Dramática.” They locked eyes. Yessenia really was a physical replica of Mirta, especially the way she expressed her anger. Both women clenched their jaws, flared their nostrils, and pinched their brows. Yessenia swallowed. “It should have been you.” She stormed down the driveway, past the aloe vera shrub Mirta had planted, and worked her key into the door’s lock. That selfish little girl. She didn’t care that Humberto’s paycheck would be short. She didn’t care about missing school. She didn’t care about how her behavior reflected on the family. He lowered his window and called to her. “Ven acá. Come here.” She couldn’t talk to him like that. Who did she think she was? Was this how all her Gringo friends spoke to their parents? “Apologize,” he said. “Discúlpate.” “You first.” “For what? For putting a roof over your head and buying you clean clothes? For paying that head shrinker for you? Tell me. For what do I need to apologize?” “Dad! You’re being really mean—” “Yours is the worst life ever, right? La pobre. No one’s suffering worse than Yessenia Sandoval. Do you know how much that fucking school costs us?” Humberto listened to the low growl of the engine. For moment, he mistook it for his voice. “We’re not rich, Yessy.” “I hate you!” Yessenia shouted, tossing her backpack to the ground. That also cost money. Humberto had driven to three Sports Authoritys to get her the right backpack. Her hands gripped the edges of the window. She spit on Humberto. Suddenly, his rage seized him. “I hate you too!” He yanked on one of Yessenia’s braids, hard, and she fell forward, hitting her chin on the car door. Humberto thought he heard a pop. After a breath and a realization of what he’d done the anger chilled. Had he really hit his baby girl? He killed the engine and opened the door. “I’m so sorry—" “Why do you get to live? And mom dies? Yessenia cried. “You should be the dead one! You! You! You!” She picked herself up and ran into the duplex. “Yessenia!” Humberto noticed the neighbor who lived in the front duplex was outside, probably pretending to water his guava tree but really chismosiando, listening. 60

He picked up her Jansport and noticed the Tamagotchi was beeping. It needed food or to be walked or something. Keeping this little thing alive was hard work, he thought while looking at the flashing digital screen. Back at the shop, Chewy agreed to let Humberto cover his remaining shift in exchange for splitting any customer tips fifty-fifty. Humberto needed all the money he could get. It still astounded him that lawyers could charge $150 an hour. They made his whole day’s pay in sixty minutes. It almost felt criminal. While rotating a customer’s tires, he talked to Nacho, one of the mechanics Humberto had started with in ’98. Nacho had three daughters, so Humberto felt comfortable talking to him about Yessenia. Nacho loved offering advice, yet a lot of his family success seemed due to luck and his put-upon wife’s involvement. “¿Qué hago? What do I do? I don’t know how to talk to her,” Humberto said, lifting the car on the rack. “We have the hearing soon.” Nacho wiped his hands. “Bueno, have you apologized?” “This again. For what?” Apologizing was one of the many things Mirta did for him. Every time Humberto had messed up (forgetting to pick her up from soccer or using one of her dresses as a wash rag or not noticing that she had changed up her hair), Mirta would sit on Yessenia’s bed and apologize on his behalf. Sometimes Humberto would press himself against the door, listening. Humberto’s parents never apologized. They would act like nothing had happened and then talk about world events, as if to say that there were bigger offenses happening elsewhere. Humberto’s spine ached. Years at the shop had ruined his posture and bones. He thought of not rotating any tires and just telling the customer he had. “She’s taking the stand in three days. The lawyer says she can help our case. She was in the car when it happened. He says she can show that it was gross negligence and not ordinary. She saw the driver on the phone. The phone! Can you believe that? And the fucker says he wasn’t on his cellphone. I need her to be normal. She can put the bad man away. And it’s like she doesn’t care!” “That’s a lot of pressure on a kid.” Nacho picked at a callous on this thumb. The skin came off 61

in a long curling string. Nacho tossed the skin onto the floor. “Were you an hijo de puta to girls when you were younger?” “No. Why?” Humberto didn’t think so. He opened car doors for his dates, never got handsy, and always understood no meant no, and not keep trying. Gestures that at the time seemed chivalrous, and now that he raised a daughter seemed like the bare minimum. “If you were an asshole to women, the universe gives you girls.” Humberto stretched his back. The movement seemed to give him temporary relief. “So what does that say about you? You have three daughters.” Nacho flashed a devious smile. “And all three have taught me to shut up and say sorry.” For two days Humberto and Yessenia ignored one another. They were like trains on programmed tracks. Each timed their excursions to the bathroom, and neither lingered in the living room. Humberto wondered if her silence was a punishment. He’d read an article about how Jehovah’s Witnesses practiced shunning. It was supposed to be so excruciating that the sinner would have no choice but to return to the flock. On the third day, Yessenia was in the kitchen serving herself ajiaco and mumbling to the Tamagotchi, which she bounced in the cradle of her palm like a sleepless new-born. This would end tonight. Humberto needed to make sure she was prepared to speak to the court and testify. The driver was a celebrity chef, renowned for his upscale Mediterranean restaurant on Alton Road. Despite what the chef had done people still patronized his restaurants, and last month has appeared in the paper with the Miami Beach city commissioner. Humberto was afraid that people would rather preserve a rich man’s dignity than honor some immigrant woman’s life. After passing the breathalyzer, the chef was escorted back to his Coco Plum house. Humberto’s goal was for the chef to be charged with vehicular homicide and receive the maximum sentencing of fifteen years in Florida. This, his attorney had informed Humberto, would not be easy. He took Yessenia’s plate out of her hands and sat at the table. He’d give the food back once things were set straight “What are you doing?” Yessenia grasped for the ajiaco. “I’m hungry.” 62

“Oye, are you ready for tomorrow? Did you look over the papers the attorney gave us? Are you practicing?” “I’m not going tomorrow. It’s stupid.” She reached once more for the food, but Humberto lifted the plate out of her reach. “Fine. I don’t want any of that nasty shit anyways. I’ll go to McDonalds.” She stood up from the table and walked out. Humberto followed her as closely as a shadow. “What do you mean? You have to. You were there! You saw him on the phone! Don’t you want to put a bad man away?” Yessenia was outside now, storming down the driveway, ignoring everything her father screeched. Soon they were on West 65th Street. She waited by the crosswalk for the light to change. Humberto stood beside her. He’d get through to her. He would. “You don’t care that this comepinga is going to get away with killing your mother?” The light changed and Yessenia bolted down the street. Humberto tried to match her speed, but the pain in his lower back returned and camped at the base of his spine. “So what do you care about?” Humberto demanded. “Tell me. What’s important to you? Trying to kill yourself? Missing school? That Tamaichi thing?” They were a block away from the golden arches. Yessenia hadn’t said a word. Once they were inside, she got in line to order. Humberto stood behind her. He used to take Mirta to McDonald’s on their date nights. He felt ashamed that the value meals were all they could afford, but Mirta always reassured him that it was all she needed to be happy. “It’s about the company, not the food. Besides, even rich people eat McDonald’s,” she told him, dipping a fry into his Oreo McFlurry. She once dared him to go into one of the tubes in the jungle gym if he wanted a kiss from her. He got stuck halfway in. He could hear her raucous laughter and snorting as the crew of teenagers yanked at his heels to pull him out. “Yessenia, please.” His hands were trembling, and his mouth felt overly dry. What would happen if she didn’t testify? Could he convince their attorney to reschedule? Maybe Humberto could talk her into a written statement instead. There were three people in front of Yessenia. Some were still unsure of what to order and hmmed and ummed. Humberto grabbed Yessenia’s shoulder—to outsiders he must have seemed like a creepy old 63

man hounding a teenaged girl, but he didn’t care what others saw or thought. “You used to be sweet. I used to tell people I had the best kid. You were so nice and happy. What happened? When you were little, you’d run up to me when I got back from work and give me the biggest hug. Why are you like this?” He rubbed his eyes. The silence was getting to him. Between not getting to say goodbye to Mirta and this he was beginning to realize that silence really was a punishment. He was owed a response. He raised her, spent money on her, worked a bullshit job for her. He bared his teeth. “When did you become such a bitch?” Yessenia said nothing. When she reached the front of the queue, she ordered a McChicken, value fries, and a soft serve chocolate ice cream. Humberto’s stomach began growling as he smelled the peanut oil and salt wafting towards him from the kitchen. Yessenia took her receipt and waited by the semi-functioning soda machines. Humberto followed. “You’re not going to say anything?” She looked away. “You were in the car with her. You saw everything. If you don’t testify, we may not win. No one will hear what happened, what we lost, what it’s like for people like us. Everyone gets to take from us. Fuck us over sideways all the time. Not this time. Please. Not this time.” Yessenia folded the receipt and looked down at her sandalias. There was dirt on her toes and heels. When her food was ready, Yessenia took her tray and walked to the outdoor dining section across from the kid’s play area. There was a family eating across from them. One of their kids swam in the ball pit, while the other worked his way to the center of a sundae. Humberto followed. He sat across from her and continued. “I can leave the room when you testify. Or drop you off and then pick you up.” His breath was quick and choppy. He felt the chapped skin on his lips beginning to crack. Humberto wished he had ordered some fries or a McDouble or something. He felt his blood pressure dropping. “Please, say something.” Yessenia looked at him blankly and then took a bite of her sandwich. “It’s not going to bring Mami back. None of this will.” Suddenly the rage of the situation, of his life, of every injustice he had had to ignore for the sake of his citizenship and family pulsed through his body. This wasn’t an offense he could disregard. The fury radiated from his back, up his shoulder, through his forearm and out his palm: He slapped 64

Yessenia across the face. She tumbled out of her chair and onto the plastic foam floor. “What the fuck?” Yessenia held her face and worked to pick herself up. The family across from them had seen the whole incident. The mother stormed over to Yessenia and lifted her to her feet. Holding Yessenia, the mother said, “I’m calling the police.” She shifted and scanned Yessenia. “You alright, baby?” “No.” The mother glared at Humberto. “Don’t you dare move.” Humberto tried to explain but the mother shook her head. She wouldn’t let him speak. He was doubtful he could articulate himself well. And what was there to articulate? He had hit her. There was no ambiguity there. It wasn’t a courtroom; he couldn’t try to make his case in the play area of a burger joint. The way the mother preened and fussed over Yessenia made Humberto feel even more inadequate as a parent. A stranger was better with his daughter than he was. Thirty-two minutes later the police arrived. Yessenia and the family testified to the assault. “…And then he hit the girl square in the face. We saw it all. I’m sure it’s also on the store’s cameras. I think I saw him kick her too. He was wild, officer, wild.” “Yes, he slapped me…Yes…Mhm.” They cuffed Humberto, read him his rights, and placed him into the back of their beat-up Crown Vic. From the window he could see Yessenia. She was rubbing her cheek and talking to the mother. After a beat, Yessenia fell into the woman’s arms and cried into her chest. The mother rubbed Yessenia’s hair. Humberto could almost hear the cooing sound he assumed the mother was making, like a lullaby. As the car lurched forward, Humberto realized he had gotten what he wanted. Yessenia testified and a bad man was being put away. Madari Pendas is a Cuban-American writer, translator, and painter. She is the author of Crossing the Hyphen (Tolsun 2022). Her work has appeared in CRAFT, PANK, Sinister Wisdom, and more. Pendas has received awards from the Academy of American Poets, FIU, and two Pushcart nominations. 65

Moonlight Goosebumps: Honey, Through the uneven emptiness Of these dancing leaves of Our favorite Kadamba tree, rain out into me as cloud soaked Moonlight Goosebumps 66

'Why do you love me?' he asked her. ' Because, you know how to love, what is love, and value love, you need nothing other than love, You dive into my eyes and breathe freely in my heart, You spill your soul into mine and I become you, I always feel how precious I am and I preserve myself for you, I always feel there is more love inside me for you, you are that dew, where my sun becomes rainbow you are that mist, where my tears grow feathers ou are that valley, where my fragrance solidifies into fruits. I know you are the lonely moon and I am the only wolf, and I know my howl will echo endlessly in your eternal moonlight.', she replied. Why do you love me? 67

Your Tender Lap: I was a nomad wandering In the streets of love Seeking a humble abode. I delved the deserts, Climbed the mountains, Hunted the pearls And slept fainted On the river bank. When woke up The river was no more But I found myself Floating on your tender lap 68

While rolling down Teardrop just halted On the lips to give last kiss, But lips were busy Holding the breath. Halt 69

About Words: Your words shall have no strings attached. They shall be hung aloft from the heart And to be wafted out from the soul. No bonding No Jealousy No preference Shall hold them back from flowing. Your body and soul may not be yours But for sure your words are. 70

Ranjith Sivaraman is an upcoming Poet from Kerala, a beautiful state in India. His poems merge nature imagery, human emotions, and human psychology into a gorgeous tapestry of philosophy. Sivaraman’s English Poems are published in International Literature Magazines and Journals from various locations like Alberta, Budapest, Essex, London, New York, Indiana, Lisbon, Colorado, California, New Jersey, Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc ,Kerala ,Texas, Chennai & Toronto. Mr.Sivaraman, was a finalist in The Voice of Peace anthology competition 2021, organized by the ‘League of Poets’ His Poem ‘Shortest Distance’ was released as Music Video in 2022. ( https://youtu.be/qOLuHGiwNMU ) 71

TRIPPED UP & Dropping to the ground 72

TRIPPED UP Sometimes when I stub I want to fall down Into fine floating Critical angle Without the landing Not our Icarus But another flyer Closer to the ground No one can stop me That’s the same problem But there’s no sunshine Near midnight in hall Travel to empty I will keep stumbling Even over nothing And end near seated Not all parallel To earth hovering Lovely but obtuse Above and never Quite finishing up Down or laid full out 73

74

Dropping to the ground The only thing dropping to the ground That may not flinch me Now is my body, different wincing. All else falling down Startles and flinches me head-to-foot And sole-back-to-crown. Then, wide ovalling around Berkeley’s 3rd World Strike Rallies, 1969, to duck arrest Again and lose my Probation to Cincinnati jail. Protests broad, multi. Still would I drop down, avoid police And National Guard, Helicoptered nerve gas, Reagan’s tests. These demonstrations New warm my heart but bring me to shake In new ways, worry. They’re past overdue and lovely in Their wide breadths and scopes. But Virus will not rest infecting. Yelling and marching Must be masked and who will quarantine To protect those loved. Everyone brings back Antebellum Not for an old South, But for the new one flinching in birth. All now should startle Over new long Civil War again. How can this one end Without a bloodying red of our States, Our states of calmed mind Thrashed into shadow and dimmed far down. ••• And I gathered in PTSD from my pregnant wife Falling out of bed, Her brain bleeding. Her recovery Never happened: endless Her loud yelling and no near recall. After 40 years At times I still cannot sleep with ease Heart, head race until Finally I rest. This is Virus, too, And startling keeps on Moving us all in new directions. ••• Terrible. Doubting How survival can manifest this Dropping to the ground.

76

Sandy 1 Hawai’i became a state in August 1959 when I was still nine in Honolulu I called my birthday dog ʻeleʻele one* black sand after my crush dark-haired smooth-skinned Sandy though no one else knew it all these years later recollecting Sandy though we never spoke 2 Weight, Love I have waited for her all these years though I have her though she may be dead and dying and still she leads me on straight paths through park and wood near her beauty temple city she is my many-eyed dark secret I call Love *pronounced élay élay óhnay

Weeping for Beings 78

Retired children’s librarian Alan Bern is a published/exhibited photographer and the author of three books of poetry. Alan is cofounder with artist/printer Robert Woods of the fine press/publisher Lines & Faces, linesandfaces.com. Recent awards include: honorable mention for Littoral Press Poetry Prize (2021); flash fiction finalist for Ekphrastic Sex (2021); first runner-up for the Raw Art Review’s Mirabai Prize for Poetry, 2020. Recent photos published include: unearthedesf.com/alan-bern https://feralpoetry.net/four-haiga-by-alan-bern/ , https://pleaseseeme.com/issue-7/art/alan-bern-art-psm7/ and https://www.mercurius.one/home/next-s-s-startle. It is clear that Alan favors both hybridity and complex collaboration: he performs with dancer/choreographer Lucinda Weaver as PACES and also with musicians from Composing Together. Thanks to Abbe Blum for her help with this sequence. 79

Today's paper offshore in the driveway its sustenance a requisite, its consequence demolishment, a heaving between fires and the ancillary columns, those antic unlives neither there nor time to awaken, the paper gives me meals, I'll let you know how that ripeness feels, the tangerines that woke you, avocados and pecadilloes, shopping carts in the afterlife, the cameras' curiosities, the tourists in their aisles, zealous pilgrims all the while in want of a toehold of a purchase, of a finite horizon amid a torrent of deals. There's a question that seats itself gingerly at the register, just what to pay for, what to steal. *** Suburban Threnody 80

Aubade Violins in the morning well before the opening bell, no thought to any breath we’ll know, as long as we may take one: Inside the cats are quiet, drowsy, no more apple carts to empty, no more dishes to employ No thought to any close impending, or so I suppose, they’ll be well done of all of this before to long. That’s how I think the story goes. *** Recent work by Bruce Robinson appears or is forthcoming in Tar River Poetry, Spoon River, Rattle, Mantis, Two Hawks Quarterly, Peregrine, Tipton Poetry Journal, North Dakota Quarterly, and Aji. 81

The Luxury of Grass The dog barks, calling to me. There’s desperation in the sound of it, a yelp that’s needy, that crescendos into a high note like a pleading question. Or maybe not. Maybe that’s just me projecting. I’ve seen the dog here at this park before, a park of just a few acres, named after a local serviceman killed in combat in a war fought long before I was born. I can’t pronounce the name, though, and it seems disrespectful to fuck it up as I do, so I say instead, “I’m going to the little park.” A brown pond sits as the undulating centerpiece of the park. Cream-colored frothy swirls of pond scum float defiantly along the banks. Kinda like a large mug of coffee. And even though I can walk around it in less than ten minutes, half the time it takes for me to drive here, I make the drive anyway and I walk the loop anyway. I disappear here. It’s the magic of the place. To look at it, you’d laugh. There’s not much beauty to be found, after all. Nothing by the looks of it that connotes magic. It’s more navigating your steps over geese shit than around flowers; it's more the squealing sound of trains brisking past along the tracks so close you could feel their wind than soothing bird chirps. You’d laugh indeed. You’d say “Ha! Magic here? HERE?! Where the pond’s fountain is so broken it spits sporadic like an angry old man, grown vicious and unpredictable with age? Here?! Where the deer carcass is still decomposing alongside the tracks having lost its race with the 7:58 commuter train to the city?” But, yes, I’d say to you. I insist there’s magic here. Humble though it may be, the rest of the world can cease to exist here. And that is, quite simply, fucking miraculous. Others come here for the magic, too. They, like me, are regulars. Having discovered what this little park offers, they come. We are all escaping here. Or finding something here. Or avoiding something. And so we walk the loop, circling, circling again, in a sober, enchanted parade. But right now the dog is still trying to get my attention. Small, scruffy, old, it’s on a lead that doesn’t extend far and the dog pulls each inch of it taut, straining to keep me in view as I walk further away. And it barks. Still pleading. Still desperate. Still hopeful. I relent; turn towards it and our eyes meet. He looks hopeful for a moment. His legs lock and his neck lengthens in anticipation of… of something. I lift my hand at my side and wave one of those awkward waves where your hand moves quickly side to side, fingers rigid and stuck together. I wave at the dog like this and then I give it a little shrug. It’s a gesture that tries to convey all at once: that I want to but I can’t; that I just don’t have anything to offer, not even to you, Dog. The dog watches quietly for a moment and barks one more time. I hear futility in it now and I’m pretty sure that’s disappointment in his eyes. Maybe it’s just my eyesight going but probably not. The other end of the dog’s lead disappears inside a shabby clunker of a car pocked with rust holes and held loosely together with silver Duck tape. But even the Duck tape is giving up hope, slowly Dedicated to Roger and his dog 82

jumping ship, curling itself into truthful despair. The car is pulled up close to the edge of the parking lot, against the cement curb that becomes a small field of trimmed, pale green grass. An old man sits in the driver seat, door swung open, the loop of the dog’s lead hooked onto just one of his fingers. His arm is stretched and unbending in a way that gives his dog a few extra inches to roam, a few more steps of grass to take. His arm must hurt, I think, held so straight for so long. With this, my own arm imagines the cramp, taking on his pain sympathetically. It’s their routine each day. They are regulars that need this park, too. Each day, the old man loads up his shabby dog into his battered car and, a few minutes before the clock hits 9, they putt-putt-clank into the lot of the park with the difficult-to-pronounce war veteran’s name because, though he cannot walk himself, the man treats his dog to the feel of some grass. Even if it is only the few square feet that the length of the lead permits. The old man’s head lifts -- from a paper in his lap? from dozing in his seat? -- to his barking dog and tells it to hush. But the command is wrapped with love and it lands softly. And so I go on, away from the dog and towards the pond to walk my loop. My loop. And as I do, I let my thoughts spill from my mind without trying to collect them. They fall amongst the geese shit. Passing the fading sign that announces the park’s name and the list of all those important people -- community leaders and do-gooders and big-pocketed people that dug out this pond and paved the path that winds around it and cut ribbons and planted the circle of trees, barely seedlings still with heavy white plastic tubes wrapped around their young, growing trunks supporting their ascent into the world -- I think of the serviceman. I practice his name, my tongue limbering up to the twists of vowels and consonants. I might even be doing this aloud, puffing out little whispers of sound that the branches of the little growing trees catch and hide amongst their leaves. In doing this, in saying his name again and again, I inadvertently conjure him next to me. (Bloody Mary, Bloody Mary…) Uniformed and medaled, he begins to walk alongside me. But his gait is lumbering, heavy with regret. I tsk inside my head, knowing we’re going to get passed by another walker at a pace like this, but I quickly feel guilty about the thought and brush it away. I called him forward, after all. He’s my responsibility now. So I slow my pace to walk with him and try to think of things to talk about. I do what I do when I’m nervous, which is to say the first thing that bubbles up into my mouth without vetting it. “It’s really nice that they named this park after you.” He just nods a slow up and down motion that makes it look like his head is too heavy for him. I’m surprised ghosts’ heads have any weight at all. And so I go on, committed to my foolishness as I am now. “It’s a really nice place,” I lie. He gives a half-smile at this and, without words, points to a sign that’s been bolted to a wooden post standing tall amongst the reeds along the pond. “WARNING. DANGEROUS ALGAE BLOOM.” In smaller print, the sign warns of eating fish from the pond or permitting a pet to drink from it, and a list of possible unpleasantries should any of the water touch any part of your body. (Rash. Fever. Poisoning. Death.) “Yeah,” I say. “That sucks.” Just a few lumbering steps further and he is pointing again. This time, his finger is directed 83