Return to flip book view

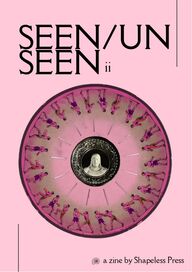

SEEN/UNSEENiia zine by Shapeless Press

SEEN/UNSEEN iiTable of Contents Preface by Glen K. Rodman“It's Worth It" by Mattie Schwartz"If I Were a Flower, Would You StillLove Me?" by Danny Valero"Disidentifying with Dysphoria" byEamon SchlotterbackMultiple works by Cameron Velez"For the Love of Sex" by Rena Yehuda Newman"VENMO" by Wendy Wildshape"The Glance" by Cora Kenfield"Watermelon Head - Self Portrait " by Oliver Lowell"Pre-Transitions" by Mx. Enigma"Cat Gender" by Steph Ferreira aka StephTheGirl"The Line Cook Escapes fromHudson" by Daisy ThursdayWritten Here, As Sand: Thoughts onTrans Historiography of Past asPresent" and "Untitled (Riis in Winter)"by Jess Saldaña .................................................page 1.................................................page 3.................................................page 4.................................................page 5.................................................page 8.................................................page 11.................................................page 16.................................................page 18.................................................page 21.................................................page 22.................................................page 29.................................................page 30.................................................page 31

Welcome, reader. Often when we say we feel seen, we mean that we feel understood. Wemight feel seen when we successfully communicate something importantand personal to another person, or when we connect with a piece of artin a way that inspires a new understanding of ourselves or the world. SEEN/UNSEEN 2 is Shapeless Press’ third compilation of Trans andNonbinary art and writing, and our second in the SEEN/UNSEENseries. What is the utility of being or feeling seen, as a Trans orNonbinary person? How can we be seen in ways that empower ratherthan endanger us? And what does this zine have to do with it?I’m not referring to representation. “Representation” as we consider it in2022, can mean too many different things. Often, the very concept isfraught with tokenization, neoliberal co-opting of radical politics andrainbow capitalism. “Representation” may mean a token trans characteron a show made by cis writers and aimed at cis viewers. It may mean asingle trans spokesperson on a panel of cis people, addressing a cisaudience. It may mean respectability politics, an effort to “prove” to cisconsumers that Trans and Nonbinary people are “safe,” “normal,” orworthy of care. In order for us to build our own self-concepts and affirm our subjectivityin the face of the dominant narrative, Trans people need more thanrepresentation. As Rita Felski writes, “We can only live our lives throughthe cultural resources that are available to us.” Trans people deserve tolive lives richly informed by an abundance of Trans stories. Notnecessarily art about transness, but art made by Trans and Nonbinarypeople for other Trans and Nonbinary people, in which our subjectivity issimply a given.Preface / Glen K. Rodman, Editor1

When I write about the utility of being seen, I am writing aboutreification of self. The part of ‘self’ that is constitutedcollaboratively, by feeling understood. By telling our stories, weallow ourselves to be vulnerable. By receiving each other’s stories,we make space in ourselves for the truths of others. A mutualexchange that, with empathy and humility, makes magic. Whateverit is that happens when the words of one person become a thoughtin the mind of another, that’s the best way I can think to describe it:magic.My hope is that Shapeless Press can facilitate this magiccollaboratively and sustainably, as a form of resistance andcommunity care. As editor, I strive to be a conduit rather than a gatekeeper. Myprimary role is to facilitate communication between artist andaudience. Emphasis on any singular artist/writer as an auteurfigure weakens us all because it discourages us from organizingand collaborating. It elevates the voices and faces of a few at theexpense of so many who need to be heard and seen. Hopefully,Shapeless Press can help erode the divide between creator andspectator. After all, publishing as an instrument of capitalism andwhite supremacy has a vested interest in keeping those categoriesseparate and distinct: author as product and audience as consumer.This is a lie. Each of us holds the capacity to be the storyteller.Each of us has the capacity to receive and interpret the story. Andno publisher has the authority to delineate whose voices aremeaningful and whose are not. But we’re just getting started: Shapeless Press is in its infancy. Ourresources are limited - right now, everyone on the Shapeless Pressteam is an unpaid volunteer, devoting many hours of labor andoften our own limited funds to make each new publication happen,because we know this work is important. We need you to hold usaccountable if we make mistakes. We need your ideas andsuggestions, so we can better serve the needs of our community. Ifyou are a trans or nonbinary person, especially if you are BIPOC, Iwant to know what Shapeless Press can do for you. 2

You tell your Nana, raised Irish Catholic, who has loved youyour whole life, and she starts texting you “how are they doing,”“what is going on in their life,” she is confused but she is trying.You tell the woman who’s showing you an apartment and shegives a blank stare, jumps to “you’ll have to forgive me if Iforget.”You change your name and the girl you met 2 months ago startsusing it and never messes up once. Your parents don’t evenbother at first. You didn’t feel like you could even tell them.Your mother says she doesn’t want to use the word “deadname,”she wants to keep “that part of you” alive.You move to notoriously LGBTQ-friendly Hollywood, startschool, and your teachers refuse to use your pronouns and yourclassmates stay silent, ignore it, but back home, somewhere farless liberal, far less accepting, your teachers and classmates bentover backwards to help make you comfortable without you evenasking.You look in the notes from a doctor’s appointment, and it is clearthat they typed the whole thing calling you “she,” and usedcontrol + f to replace it with your full name. They don’t careenough to just use your pronouns. That would be too difficult.But your Nana texts you, asking “how they’re doing.” And yourfriends never misgender you. And you move back to yourhometown and go to the college you swore you’d never attend,because it’s worth it. To be seen for who you are, to beaccepted, to have your voice not only heard but amplified, to notonly be liked but loved, not only tolerated but accepted.It’s worth it.It’s Worth It / Mattie Schwartz3

If I Were a Flower, Would You Still Love Me? /Danny Valero4

In part, gender dysphoria is an emotional experience of misrecognition. I’mthis but I want to be that. I’m a girl, but people see a boy. I imagine this is whythe mirror trope appears so often in trans-related media. No matter howpersonally annoying I find this convention, being dissatisfied with what onesees in the mirror is ultimately a pretty effective shorthand for one aspect oftrans life. In his book on trans autobiography (another kind of self-reflection), Jay Prosser argues “the difference between gender and sex isconveyed in the difference between body image (projected self) and theimage of the body (reflected self).” In his view, the drama of a trans personlooking into the mirror is a literalization of the drama between mind andbody, the interior and the social, sex and gender. Dysphoria is then the visible mismatch between any of these elements. Theway we fail to match. And the way of clearing up this incongruity istransition. We wear clothes that make us feel more comfortable. Learn tocarry our weight differently. We take hormones that reshape our bodiesand undergo surgeries that alter the landscape of our flesh. Transition is akind of salvation, a life line thrown across the infinite gulf between the selfand the elusive mirror image.But as many trans people (or for that matter, disabled people, fat people,people of color, women, etc.) know, the mirror doesn’t simply reflect reality.The play of light on mirror’s surface creates glares, distortions, strangewarpings, projections, and optical illusions. The image in the mirror is notsome kind of plain visible truth. What we see is a reflection of the socialnorms have shaped us. Disidentifying with Dysphoria / Eamon Schlotterback11 Prosser, Jay. Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. Columbia University, 1998.5

The way we were taught to understand beauty, wholeness, masculinity,or even humanity. If transition helps bring the person and their reflectioncloser together, the endless, shifting cruelties of the mirror will nevertruly allow us to embrace our image. We also have to find a way to loveour misshapen image.One of my earliest memories is wandering into my family room as a childto join my dad watching a movie. On screen was a sweaty, frantic man,shouting and waving a gun. I was too young then to recognize the iconicfriend of the dolls that was Al Pacino as John Wojtowicz in Dog DayAfternoon. But my dad soon explained, inviting me into a male initiationrite by means of a shared joke at a nelly’s expense. “This guy is robbing abank,” he explained gesturing at Pacino, “so he can get enough moneyfor a doctor to turn his boyfriend into a girl. Isn’t that silly?”Of course, I knew to agree. It was silly. Nonetheless, my psychic worldhad just ballooned to make room for the possibilities my dad’s little jokerevealed. I had just learned that a man could have a boyfriend. And more– a boyfriend could become a girlfriend. The joke had backfiredtremendously as the intended initiation into manhood had instead silentlylaunched me into transfemininity. The queer theorist José Muñoz callsmoments like this, where we identify with a scene designed to precludeidentification, disidentifications. Disidentification also provides thestructural logic of the camp aesthetic, which according to Muñozinvolves a kind of queer identification with the tacky, the ugly, the failed.2Muñoz, Jose Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Politics ofPerformance. University of Minnesota, 1999.26

A few years in, I am very happy to continue my medicaltransition. My new pronouns, the hormones I take, themakeup looks I can do – they make life livable. But there’salso, I think room for a strategy of disidentificationalongside transition. We can look in the mirror and say, “Iwill mold this image to my will.” But we should also look atour reflections and say “I love you. I love you now,broken, unfinished. I see a glory in you in excess of whatsociety says a woman should look like.” I have come toaccept that dysphoria will continue to shade myexperience of the world. I will never fully inhabit thenorms of womanhood I find myself both trapped withinand locked out of. But in the struggle to exist in a worldthat wasn’t built for me, I can embrace a vision of myselfas I am -powerful, radiant, goofy, hairy, flat-chested,beaten-down but rising up. A camp embrace of ourdysphoric self-image is maybe an impossible thing toexpect. But transness is a technology of achieving theimpossible – of reshaping the human body, oftransgressing society’s most sacred taboos, of becomingotherwise. I’ve already done the impossible, just byachieving an identification with a trans woman in the verycontext meant to make such an identification unthinkable.I do the impossible everyday when I bundle myself infeminine armor to survive a cruel world. I can do this too.7

The Skeleton and The Closet (top) & Husk (bottom) /Cameron Velez8

My Eyes Are Up Here (top) & Partus (bottom) / Cameron Velez9

Sit/Stay (left) & Self Care (right) / Cameron Velez10

At age 22, I did something very dangerous: I decided thatsex was an important part of my life. I had known this about myself since I was very young. Itwas the conscious decision, not the desire, that felt new.Frankly, all this time I hadn’t known it was an option. I grew up a genderfucker, a little tomboy ringleader kidwith an extremely active imagination. My obsession withBuzz Lightyear was all consuming and extremelycharged. I played fetish games with friends involving sex-changes and pseudo-slavery in after-school care before Iknew why it made me tingly down below. I wrote gayslash fanfiction insatiably throughout 7th grade yearbefore turning that same energy on our three malemiddle school teachers, publishing that story piece-mealon DeviantArt. My crushes were always apocalypticand flamboyant, on grown men or boys at least a coupleyears older.For The Love of Sex / Rena Yehuda NewmanWhat’s more, I refused to stop talking about them. While mycompatriots spoke in hushed tones about the guys or girls they wereblushing about, I was shouting from the rooftops how much Iwanted Mr. So-and-So to smash faces with Mr. Such-and-Such,passing around my sketchbook filled with homoerotic cartoons ofcharacters in compromising situations with less-than-vaguely eroticundertones, and waxing poetic about wanting to keep that hot Seniorin my gym class as a pet in my basement. So, for many of my friendswho often adored hearing tales of my shameless infatuations, it wassurprising that such a precocious sex drive would result in such adud sex life. 11

Though I didn’t “transition” until I was sixteen, it turns out that youdon’t need to be out as a faggot to experience the world like one.Nobody ever really bought that I was cis, even after I grew out myhair from that one boy-summer haircut that lasted a few years tilwomen gave me dirty looks in the restroom. And as much as I wantto tell tragic tranny stories, the marker of my gender deviancy wasalways my sexuality – my hunger for boys and their bodies, and myabsolute refusal to speak of it with any decorum at all.Of course, I learned shame like all of the rest of us, often asretribution for my unwillingness to play by the standard set ofromantic rules. Someone would steal my sketchbook and show it tothe object of its depiction. A friend would insinuate that it was grossto only watch a TV show because you liked the fanart of twocharacters making out, wrong to imagine two favorite teachersboning in the break room. Boys would look at me, frightened to thepoint of vague violence, when I brushed their shoulder, sat too close.Others would have long, emotionally-involved texting or even sextingrelationships with me that could, for some reason, never beconsummated in person. Shame occurred slowly, as if by osmosis. I eventually started actingon it when I managed to finally acquire myself an acceptablepartner who could take me to homecoming; coupled in 10th gradewith a sweet, normal straight boy, my promiscuous heart learned toburn off its chaotic and many-pronged passions into stumps,redirecting my simultaneous fantasies about a million men to mynow-acceptable, one (1) high school boyfriend. I knew it would becheating to think of others from before or imagine the others afterhim, definitely unacceptable to imagine him kissing all of those boyshimself -- so I just wrote a few pretty love poems for him and called ita day. Once you have something real, you’ve got to stop fantasizing,right? There’s no need for imagination anymore once you’ve got acertified Relationship. 12

I broke up with him after a year, having held out a littlelonger than I’d have liked to because I still liked havingsex after school. I came out a few months after, nocoincidence. He remains the only “official” boyfriendI’ve had til this day.By the time I arrived at my state school university, I wasswallowed up in a sea of white kids from midwesternsmall towns and suburbs with sexual norms to match.With my buzzed haircut and seventh-grade-boy-chicwardrobe, I was a goner. A lonely four years passedwith a handful of shitty hookups with closetedbisexuals and one particularly abusive emotionalentanglement with a non-boyfriend who died from hisown shame every time someone suggested we weredating. While everyone else got it on, I felt like somestunted reject, continuing to pine after an older crush ortwo and jerking off in the evenings like a sad little runt.After an adolescence and collegiate slate deprived ofthe legible courting rituals and romantic games mystraight peers played, I finally started fucking becauseof three gifts: two years at a co-op surrounded by thelove of other queers and faggots, the COVID-19vaccine, and Grindr. Once I got a taste of the variety,splendor, and magic I’d been wanting, I rememberedwhat I already knew, even since I was so little: sexmattered to me -- and I wasn’t going to pretend that itdidn’t ever again.13

However, when you decide that sex is an important part of your life, peoplearen’t happy about it. In fact, people are largely unhappy about it. Doesn’t really matter much ifyou’re queer or straight; try telling that to your family dinner table or bringingit up in a seminar. At a work meeting, just make a little announcement. Why’sit so different than a nice lady telling everyone she’s pregnant, or yourcolleague letting the team know he just got engaged? Maybe people justprefer a little gift wrapping around their genitals. Euphemism keeps the wholeship afloat, and adults who don’t (or can’t) follow this convention getpunished for it – and not with a firm spanking. What are faggots or throuples or swingers or sluts or kinksters who weartheir leather out of the house but people who have decided, in a significantand visible way, that sex is important to them? These are simply people whohave decided to prioritize sex, or variety and type of sex, as a salient part oftheir lifestyle. Yet, their mention by these terms is enough to conjure looks ofdiscomfort (or disgust) in proudly liberal identifying communities. The reasonis because sex is considered obscene, and someone who believes otherwisemakes themselves obscene.14

This is really what’s at stake when we’re talking about the buzzwords ofgender and sexuality. Straight, vanilla people get to cheat by pretending thatthey’re not horny and that their sexualities are properly contained. Theyrely on this assumption to excuse them from ever addressing the sheerenormity of shame that drives their unconscious waking life every time theyfeel even a little aroused. But not everyone gets to play that game. When Iwalk into a room of strangers with my ambiguous, loud gender, mytestosterone face and effeminate mannerisms, I don’t have the great luxuryof pretending people aren’t thinking about what’s in my pants, how I fuck,and calculating exactly how threatened they should feel by that. If I’m awoman, I’m a butch. If I’m a man, I’m a fag. Best of both worlds, my veryappearance conjures up questions of sex. It doesn’t matter just how much Istay polite, it’s too late: I’m already perverted and beyond the pale. They are angry that I didn’t try to hide it; I could say I was “born this way”,but the truth is that I chose it. Maybe I could try to bury my love of sex, but Idon’t want to. It unlocks secrets, shows me the most beautiful parts of theworld my Maker gave me. I’m hungry for it, have spent a whole younglifetime preparing to explore and exalt and express it. I adore this part ofmyself and always adore seeing it in others, especially trans queers whohave decided for this reason (among others) the body is well worth living in.Yet we all get spurned, having made the choice to value what the culturedenigrates, regardless of the cost. That’s what makes someone deviant anddefiant.We might as well beat them to the punch -- and have fun while we’re at it.15

VENMO / Wendy Wildshape16

17

When I first came out professionally, I knew I was goingto be the only trans woman at my workplace. I’d heard somuch about the questions to expect, and tried to get out infront of it with a six-page brochure answering all thecommon questions. At first I was overwhelmed by what felt like anoutpouring of support from people across my network.And then I experienced the other side of visibility.I started getting The Glance.–Maybe I’m at a meeting, maybe it’s lunch, maybe it’sshooting the shit over Zoom. Something tangential to ourwork that involves trans issues will come up, and one ofmy colleagues will share their take on it. They pause.And the same way the Psalms of David ended a stanzawith selah, or frat boys last decade invoked no homo, theydeploy The Glance. It’s an attempt to make eye contactwith me, but more than that, it’s a hope that I’ll returntheir gaze. I’ll lock eyes, and maybe give them a barelyperceptible nod and a look of understanding. “Yes, Cis, you’re able to say that.”The first time I noticed it was right after someone said“They-them pronouns are so confusing.” “Cora,” their eyes plead, “I want to support you, butplease know that it’s hard.”The Glance / Cora Kenfield18

The most recent was right after a monologue on how Elon Musk’s transphobiahad a silver lining: maybe Republicans would start buying electric cars.“Your suffering isn’t in vain,” said his eyes, “it’s helping save the world.”–It isn’t limited to the workplace. Friends locking eyes after using he/himpronouns to describe who I was before I came out. Lovers leaving pregnantpauses after assuring me that they wouldn’t mind if I ‘got it chopped off.’The most surreal was right after a Grindr hookup, about a month before mybottom surgery. The same guy who pulled out his phone to watch trans pornwhile inside me wanted to talk for an hour after. Hollow compliments abouthow pretty I was, positive feedback about how I was “about to become awoman.”How I was “a real transgender, not like those kids down in Florida.” And then The Glance.“Tell me it’s okay I voted for DeSantis.“Tell me you ‘understand the nuance.’ “Tell me I’m not gay.”–19

The hardest part is knowing how important being visible is.I’ve seen how my presence has softened the hearts aroundme. I know that, by virtue of them finally having a transperson in their life, they see us as people. And that’s great,and important, and valuable.But I also end up standing in for the entire trans community.An ambassador. A spokesperson. An ombudstrans.And at that intersection of familiarity and visibility, I see thebirth of its consequence.I see The Glance. 20

Watermelon Head - Self Portrait / Oliver Lowell21

My gender was predestined for a path, that most of the cissy heteroworld won’t ever know! What is the life I should be aiming for a unwanting marginaltransfemme?Where do I go? I am on my own. I don’t see people like me. Istruggle being different, smiling, all while knowing I am unhappy,miserable, scared.What do I do to feel content, safe, secure, valid, affirmed, and nottriggered by my surroundings? What am I willing to sacrifice?What rules do you follow when there is no playbook for yourgender?Will I ever be comfortable having a Shenis with Moobs?Will I be desired with the body I have? Who will ever love me?How am I supposed to love me?I am scared to be me. At times I hate myself, or at least transphobiaI’m to thank! Not being able to think straight, trapped in my mind, scared tochange. Partially conflicted with dysphoria and absorbing thechristian right’s anti-trans narrative. Is it worth the transition?Pre-Transitions / Mx. Cleo Mizrahi22

Do I need to work on my body image and how cis-beautydestroys me or do I need to work on beautifying my gender?Will my transition be beautiful, where I can wear girlyclothes, and blend in as a woman?What if I don’t pass as a Mizrahi barbie?I fear of having to go through so many changes in order tofind contentment.The fear that my fantasy is just a myth. Boys will not look atme as cis-girls, no decent man will want me my father wouldremind me! I will never truly be a girl, nor I’ve ever felt I wascomfortable as a boy. Why must a layer of flesh separatesme from other cissy womxyn?FUCK STRAGGOTS!Transfemmes having to question how one should look toappeal Cis-society and by feminizing our expression, do webecome obsessed with maintaining our youth?Worried I HAVE FAILED MY GENDER, I AM WEAK,not like those cunty ballroom Tgirls, piercing through theworld with their realness, while us theybies erased in thebinary.Going back or hiding in the closet, often feels like a selfimprisonment of my Divine Femmeness! I’m told by my “allies” I should crawl to fear a truthful darklife, where my inner femme must hide, to get by, cause thisworld, isn’t made for Sissy to thrive! 23

Am I strong enough to be able to shrug off my environment's perception ofme, and continue to be different?Do I have what it takes to keep nourishing my evolving gender, leve by level? Must I be a non-hatching Tamigachia for the rest of my life?Why can’t I pee freely, or fear it will be harder to go to the bathroompeacefully?Will Cis-Femmes ever understand the difference of transmisogny and theirversion of catcalling when we are glamming ourselves out to strut in public?Who ingrained in me a;; this fear that I have to accept that I’m different bydesign, and my life is set in stone to be harder? Where is the normalization of puberty for tgnci baddies? Can’t other kidsplay “cooties” and show their bodies firmly growing, then pointing andclaiming “we know you’re fooling” us?IDK IDK IDK IDK IDK IDK24

What does my transition look like? Realistically v.s ideally?Do I need to be a woman to wear the things I love, not clocked andcalled she/her?Do my genes make me stuck to be AMAB? Too many features tocount as not enough to pass! Why does my soul and body unmatch? Can I transition without anxiety? Can I transition without beingouted in this hood?Do I have to accept my path and go down this road to be free ofpain? But I don’t have the hair for it, I don’t have the body for it, I don’thave the look for it, how can I possibly enjoy being a girl.What does it mean to be a woman? Is it being all beautiful, andfeminine, and having a certain body?If I keep my penis how embarrassing it would be to wear certainclothes and have my privates showing. Do I stay on the path that I was born into or do I create my own? 25

Why me?Who am I ?What am I ?What am I searching for? What is my gender pronouns?How do I not internalize who I am?What is normal? Do I have to accept being other than “normal.”Will I be seen as genderful? Is doing drag enough to feel content?Am I a genderqueer, transwoman, or just a fucking rebel?What is my ideal gender presentation I should aim for?What will make me comfortable, be able to breathe, and be at peace withmyself?Am I just confused, mentally ill, cursed, or stuck with a misunderstood diagnosisassigned?How can transitioning be happy if it's all pain, suffering, microaggressions,social issues, and legislation that keeps forcing us to hide, cry, be ashamed, anddie!Amerikkka can’t handle us! Patriarchy is terrified of us! We must not be afraidof us! DO YOU FKN HEAR ME TR&%$IES ?!?! 26

What if I desire to go back to being a male? Wouldn’t I be safer by closeting who I am?Is transitioning how I will truly embrace who I am?Why does transitioning need to be binary, and only acceptedthat way in society?Is there truly a way to be out of my shell?Will I have to change my name again?HOW MANY STEPS WILL I HAVE TO TAKE TO BEAT PEACE WITH MYSELF? WILL THISTRANSITION HAUNT ME MY WHOLE LIFE?What if my “life-saving” surgeries goes wrong? Will the terfsin my life claim “I told you so?”What should be the determinant to transition? What is a validreason to transition?Is being a girl meaning to dress, act, and display in a certainway?What does being unconflicted look like?Will becoming a woman make me content?Will I ever fulfill the life of a woman I always fantasized? How will I look like? 27

Would I be able to hide who I was, and live a new life?Will people still recognize me?How long must I hide and wait to be free? Who will accept me? Why can’t I be an anatomical male and wear a dress & ya’ll leave mealone?Why G-D, claim “I’m made in your image” and leave me by cissys whowant to kill me?Do I continue to hide? Do I continue to fight? Do I continue to believe intrans liberation? Why must I obtain sharp tools to protect me, when my Humxnity should beenough to let me be?To whom do I turn too to guide me towards a protected class? Must I live infear for who I am inside as Mulan would sing, or go through the world,with the comfort, that my gender I’m hiding isn’t safe in this cisociety, and Imust pretend the rest of my days, as a inauthentic “man” to survive withoutharm, barriers, lack of privileges to my grave, since heteronormativity isn’table to function with my resilience displaying femme supremacy! Uncurse me with your casted transphobia, and earth my hormonal plea tobe equal in our lives!.When my time has come to lay me in the ground, may I be remembered asa Humxn, not trans, or my deadname, how good or bad I was to myenvironment, but my flesh, bones, and imbalanced hormones didn’t stand inthe way of being buring with my humxnity 28

Cat Gender / Steph Ferreira aka stephTheGirl29

The Line Cook breaks free from hudson!A brisk Thursday morning walk to the amtrak. Southbound. two hours,he’s got his Carhartts on and a newly shaved face, his hat pulled low.quickchange in the amtrak bathroom- bombshell blonde wig and whateverdress was grabbed from goodwill in 30 seconds flatShe's in the village, The Monster, a vegas inspo homo piano joint withshowtunes and a hunk bouncer. mirrors and rhinestones every which wayflatter the aging gay patrons shes got the best seat in the house and shes unable to look away fromherself for the first time the pianist is built like a scarecrow and covers the classics.the free world she's wanted is reflected around her, dazzlingly. Has beenchorus boys, a concierge who sang at Carnegie, queens, dykes, daddies,and herself all singing and dancing and drinking and loving.by monday the wigs away and the boots are on and the line cook is back onthe job, scrubbing a floor miles from the music, beard growing, crossdressing alone in a mirrorless rural bedroom 11 months later and the cook's career is kaput; heavy is the head that wearsthe double life! She’s home free and here to stay!Landed, and loving it.The Line Cook Escapes from Hudson / Daisy Thursday30

The afterward of In the Dream House by queer/Cubanwriter Carmen Maria Machado references an essay onJoanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing by LeeMandelo, who notes that women’s lit history is “written onsand”. So, where does this leave trans history? I look down atmy body and think, trans history is quite literally written here,on and in our bodies. Living bodies that retain scars andchemicals, recovering bodies, mysterious bodies. Bodies whichmay very well turn to sand one day, sand that holds the tracesof everything we have been exposed to— hormones,pollutants, lovers, haters, dust and all.What to make of the material of sand? As it is such a shifting,changing thing or rather it is a group of things – a make-up offine particles that compose a single body. A sedimentary layerof our time on earth. A commodity. An island. Could it be thatit is all that’s left in the aftermath of our time together as transpeople, in the company of each other within an hourglass ofchange, which also tells the time? Our time. We only haveeach other and no one is free until we are all free. As I amwriting this, I accidentally misspell ‘each other’ as eachother-and a thin Microsoft red line appears beneath it, a scar oftogetherness.There is no way to travel through space without time. Thechemicals in our bodies also follow this rule as they dispersewithin us, invisible to others, but very visible and felt by us. Afate only recognizable by time-lapse, the slow change ofgrowth of getting harder, getting softer, the hyper-visible-invisibility of the movement of the opening of a flower beinglivestreamed across the world.Written Here, As Sand: Thoughts on TransHistoriography of Past as Present / Jess Saldaña 31

A series of photographs by Felix González-Torres illustrates thebeauty of sand’s way of capturing the traces of presence leftbehind by both human and animal. Like so many of his works thetitle is “Untitled” with sand as a parenthetical, reading as“Untitled” (Sand) 1993/1994. As a viewer I have wondered whyhe uses “Untitled” to title so many of his works. It is thatcontradiction- of needing a title, but not wanting one- which is forme also a question for any title, any position, any identity that wechoose or is thrusted upon us as social beings. González-Torreswas actively involved in the queer movements of the 1980’s andwas himself HIV+. If you can imagine, the friends and lovers hesaw disappearing left and right of him, leaving only theirfootprints behind. Leaving only the ghosts of the memories withinhim, until he too passed from the illness. Illness is also somethingthat is both visible and invisible at once- that is, it’s hard to knowwhat’s happening unless you look under the surface, into theblood and guts of the living thing. It requires a certain level ofdepth, of care.In Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s preface to the translation ofDerrida’s Of Grammatology she writes on the philosophical ideaof “being under erasure”, which is an attempt to free languagefrom the fallacy of a fixed origin. That every mark made,including the marks of language, indicates an absence of whatcame before- a present past that can never be wholly retrieved.Any given word is also what it is not, and what it has yet to be,existing in the past and future at once, obliterating meaning.History itself, is made up of a kind of erasure, where everythinghistorical can be written because there are histories that areirretrievable. She remarks specifically on the idea of the footprint,which indicates an absented-present, that is ever present in itsinvisibility. It is what is present for me when I view the photos ofGonzález-Torres. Analog photos of black and white, made byimprinting light onto the surface of a camera; another way toarchive life is indeed in the wake of its disappearance. 32

Sand is also the primary substance that makes glass. Glass, a notoriously sharpand breakable substance liquifies with the energy of heat, and is then able totake any form imaginable, any form the artist might dictate. As trans people, weare all somewhat artists of our own bodies, in our own right. Perhaps, transhistory is written by the hand of the sculpture who finds form in the bends of acrystalline glass, whose cracks tell stories of love and societal betrayal—amongother things… Or perhaps it also takes lightning to tell this story? When lighting strikes theground, it fuses sand in soil into tubes of glass called fulgurites. When it strikesa sandy surface, the electricity melts the sand forming hardened glass blobs. I dobelieve it would be hard to tell our narratives without electricity- our bodiesafter all are conductive and the currents move through us in waves. “I sing thebody electric” It would be hard to tell my history without my father, who did trade schoolinstead of college, becoming an electrician. He was homophobic, and I’m notsure he understood what being trans was, and I’m deeply uncertain of what hewould think about me being trans- he died when I was 18, a solid 5 years beforeI identified as trans/enby. Sometimes I think he died in a war. The war beingwaged by the medical system, of which trans folks also suffer. It is an invisiblewar. A war you must learn about by entering it, sometimes with no otherchoice. If only he could understand that we were on the same side—fighting thesame things. The racist, sexist, transphobic medical industrial complex, one thaterases as it numbers its bodies. Dad, don’t you know? We are on the same team. We are on the same side.We are all just grains of sand.33

Untitled (Riis in Winter) / Jess Saldaña 34

SEEN/UNSEEN II was a zine by Editor....................Glen Kalliope RodmanDesigner...............Amalia VavalaIn conjunction with..........PRPL PPLCopyright...........Shapeless Press, 2022 Shapeless Press can be found online atprplppl.website/shapeless-press "Different Perspective" p. 13 courtesy of Carlos ZGZ