Return to flip book view

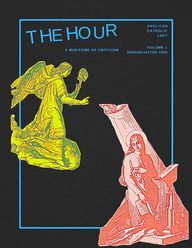

ETHHOURA M A G A Z I N E O F C R I T I C I S MA N G L I C A NC A T H O L I CL E F TV O L U M E 1A N N U N C I A T I O N 2 0 2 0

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T ST H E P E O P L E N E E D T O S E E U S D O I N G S O M E T H I N G C A L E B R O B E R T S T H E C H U R C H M U S T A D D R E S S C L A S S D I V I S I O N S M . K . A N D E R S O N T H E L E I S U R E O F A L L B E L I E V E R S B E N J A M I N C R O S B Y W A K E T O S L E E P M A R Y D A V I S I N S P I R I T A N D I N T R U T H : T H E S O C I A LC H A R A C T E R O F T H E E U C H A R I S T T O N Y H U N T L I T A N Y F O R L A B O U R PERCY DEARMER C H R I S T I A N I T Y A N D S O C I A L I S M PERCY DEARMER 03081115192936

0 3 T H E P E O P L E N E E D T O S E E U SD O I N G S O M E T H I N GT H E H O U ROur intent for the drafts of our respectiveeditorials for this issue, written before theshutdown was imposed in the face ofCOVID-19, was to address theproblematic distribution of “clergy time” inthe structure of parish administration. Butthat was then. Now that the shutdown hasrequired clergy to create alternatives to“normal” parish life and pastoral care,clergy time has become an exception tothe rule and thus our original analysisbecame less than applicable. But a state of exception is a revelatorystate: the suspension of the rule exposesmuch of what was once considered“necessary” to have been arbitrary allalong; on the other hand, whatever isretained no matter the cost is revealed tobe the actual rule that constitutes theorder of things -- the rule that persists inspite of the exception. The shutdown is clearly such a state ofexception, of exposure. And for ourparishes, where services have beenindefinitely cancelled, it has exposed theunderlying rule that determines, amongother things, the actual function of clergy in the parish. To navigate the remainder ofthe shutdown and beyond will require usto face the hard questions that the relativepredictability of the old rule allowed us toignore. It will require us to face theexception, which is the same thing asaccepting that a new rule is now in place. At first, my main concern was specificallywith how clergy time is consumed bycompensatory labor: the efforts wherebyclergy attempt to fill some vacuum in thelife of the parish. Aside from accountingfor a great deal of time and effort on thepart of clergy, I also began to notice howthe distribution of clergy time was beingdirectly conditioned by church decline andthe subsequent drop in lay leadership inthe organization of parish life.Compensatory labor is thus a category ofits own, neither directly pastoral, liturgical,or even administrative in nature, though itwill often take the shape of one of thoselatter functions. As its name suggests,compensatory labor represents theexcess investment -- of time, energy,emotion -- demanded from clergy tosupply for the lack thereof in the parish.

0 4 T H E H O U RWhile this was clearly evident in thefamiliar situation where clergy instinctivelystarted running programs that were oncehandled by parishioners, it wasparticularly found in the effort required tomaintain the parish’s online presence -- atask that often falls to clergy. It was thesecommunicative tasks -- performed in thefrequent production of “content” acrossmultiple social media platforms and evenin just the act of informing thecongregation about what’s going on -- thatsuggested that something more was goingon than priests making sure that the altarfrontals were switched out. That so much compensatory effort isbeing directed to parish communicationreflects a basic alienation between clergyand their parishioners. People’s lives aredistracted and fragmented, and this putsenormous pressure on a structure ofparish life and ministry that presupposespeople’s routine availability. And since thisis a social and relational alienation, theimperative for clergy to compensate for itentails a significant demand upon theiraffective resources as well. Clergyobviously do what they do because theysincerely care for their congregations, butthis compensatory labor has a way ofexploiting the sacrificial character of the priesthood, such that clergy begin toliterally care for their congregations -- as ifon their behalf. They must find inthemselves alone the emotionalinvestment that would ordinarily besupplied from the congregation as awhole. As I saw it at the time, the impulse behindthis compensatory labor was to maintainthe existing structure of the parish atwhatever cost. The parish must alwaysappear to be what it always has been,with everything in its right place andmaintained accordingly. But it has beenremarkable to watch this all develop in themidst of the shutdown. Clergy should nodoubt be commended for their valiantefforts at “keeping the candle burning,”but this crisis has nevertheless exposedthe underlying incoherence of how we “dochurch” -- or at least of how we didchurch. Vital questions have emergedabout the role of the priest vis-a-vis thelaity; the minimum requirements by whicha mass is considered “lawful”; the extentto which a liturgy can be abstractedthrough virtual communicationtechnologies before it ceases to be a“liturgy” in any meaningful sense; andwhat, if anything, we are being spirituallyand theologically deprived of by the

0 5 T H E H O U Rprolonged suspension of the mass. All ofthese questions orbit around our basicuncertainty about the nature of the parishand the relationship of the clergy to it. But a more immediate question concernsthe widespread production of live-streamed liturgies. Because,notwithstanding the obvious benefit thatthey are providing at the moment, live-streaming liturgy epitomizes thiscompensatory and communicative labor.To be clear, no priest could possibly befaulted for making use of the technologieswhich can facilitate virtual liturgy in themiddle of the shutdown. Nevertheless, it isstill important that we understand thebroader context in which thesetechnologies were already situated. Wefind ourselves in what theorist Jodi Deanhas called [1] “communicative capitalism”-- that is, “the form of late capitalism inwhich values heralded as central todemocracy materialize in networkedcommunications technologies.” But thevalues that are “materialized” bycommunicative capitalism are not limitedto those of democracy or politics; thevalues that would be more recognizable inour churches -- those of community,hospitality, fellowship, and accessibility --are also included. Of course, even before the shutdown, few of us ever imaginedthat Facebook or Instagram were purelybenign or neutral, but it’s their necessity tothe operation of communicative capitalismthat accounts for the feeling that wesimply have to participate in them; oursense that they are somehow imperative.Because communicative capitalism“directly exploits the social relation at theheart of value,” our social relationsthemselves are now the primarygenerators and markers of value. Undercommunicative capitalism, in short, thesocial “value” of an individual or institutionbecomes increasingly measured in termsof the “visibility” of their online presence --the visibility as seen by a distant beholder,that is, who registers their experience by“liking” the content, thereby increasing theaffective “capital” represented by theprofile. To not participate in the frequentproduction of content; to not configureone’s relationships or institutional identityon the platforms of social media, istherefore to withdraw from thecommunicative exchange of valuealtogether -- which is to effectivelybecome isolated and invisible. While parishioners have a legitimate needfor clergy to produce virtual liturgiesduring the shutdown, one can detect that

0 6 T H E H O U Rclergy are motivated by an implicit need oftheir own, which is that the people need tosee us doing something -- to see us, thatis, online and on social media. Thesecommunicative technologies haveenabled us to imagine that there is arealm in which worship and parish life canbe conducted that is entirely other thanthat of actual life; that a parish can andmust “do church” on two fields at once, soto speak. All of this was in effect wellbefore the shutdown was imposed, just asclergy were going to great lengths toensure that people could see that theyand their parishes were doing something.Not only is this a near-perfect expressionof what Mark Fisher identified [2] as the“meta-work” of administrative labor -- the“simulation of productivity” that substitutesfor the actual productivity that is evermore elusive -- but it also reveals theextent to which clergy have unwittinglyaccepted the reconfiguration of value asdetermined by communicative capitalism. The people need to see us doingsomething. The irony of the shutdown is that it hasrestricted parish life and ministry to thevery technologies by which its value insociety is being measured. So, while it’sentirely possible to affirm the benefits thatthese technologies have provided, theircontinued use could likely bring the life ofthe parish -- particularly its liturgical life --into further alignment with the logic ofcommunicative capitalism. Because theeffects of the shutdown will almostcertainly outlast its immediate restrictions,this means the virtual simulation of liturgyand fellowship will not remain a merelytemporary alternative for long. And withregard to clergy time, specifically, theshutdown and its aftermath couldpotentially reinforce and even expandtheir compensatory function. In theabsence of masses to celebrate,programs to run, classes to teach, peopleto visit -- all of which presuppose theparticipation of the parish -- clergy couldfind themselves tasked with theresponsibility to represent the parish in away that would even impress theclericalism of ancient times. All whilefurther obscuring the intelligibility andnecessity of a localized and offline modeof parish life. One does not have to look back morethan a decade to recall a time when noneof the technologies that are presentlyfacilitating our virtual liturgies existed. If apandemic were to have required a

0 7 T H E H O U Rshutdown back then, clergy would havegone about caring for their people as bestthey could -- with phone calls and notesand emails -- but there would be littlevisible evidence of any of it. Nor would ithave occured to anyone to expect there tobe. To remind ourselves of this is not toengage in some kind of ludditecontrarianism, but is rather to insist thatwhat is deemed to be “necessary” at anygiven moment is rarely singular orexclusive. More often than not, there aremultiple “necessities” that one can choosefrom -- each of them inextricably bound tothe present situation, of course -- butnonetheless distinct from each other. Thereflexive impulse to live-stream everythingis no more a “necessity” than the decisionto consider instead -- as Tony did in ourlast issue -- the fact that both clergy andlaity are so geographically dispersed anddislocated from the local parish andrespond accordingly. Likewise, theimpulse to produce videos for parishionersso that they aren’t left without any spiritualexercises betrays our anxiety about theimpoverished state of our formation andprivate devotion. Acknowledging thatwouldn’t automatically resolve the issue,but it would at least refrain frompresuming what is always the optional useof social media and communicationtechnology. The acceptance of the actually-existingreality need not ever be defeatist. So weshould probably keep producing virtualliturgies and maintaining a mostly onlineparish life. However, the time will sooncome when we will have to attend to thequestion of what the parish actually is -- ofwhat parish ministry consists of -- beyondthe makeshift exceptions that we havearranged for the moment. And while theshutdown required us to set aside theproblem of clergy time, the shutdown itselfwill insist that the problem remain frontand center. The compensatory labor ofclergy is a rule that has persisted in spiteof the exception, which means that theshutdown won’t break it for us. Caleb RobertsChampaign, Illinois[1] Jodi Dean. “Communicative Capitalismand Class Struggle.” Spheres: Journal forDigital Cultures. November, 2014. [2] See “The Privatisation of Stress” and“Democracy is Joy” in K-Punk: TheCollected and Unpublished Writing ofMark Fisher.

0 8 T H E C H U R C H M U S T A D D R E S S C L A S SD I V I S I O N ST H E H O U RWhen I first conceived of this article, I wasgoing to make a case that the economicinequality Millennials faced following the2008 financial crisis had left them themost impoverished generation since theGreat Depression. This class divide,between the generations, meant thatthose in leadership—mostly Gen X andolder—inhabited a parallel America. Theirhousing was already secure, their childrenborn, their careers started. The povertyMillennials have faced are not the typicalstruggles of youth, but a severe economicand public health crisis that has beenmocked and left unaddressed by bothsecular and religious authorities. WeEpiscopalians are facing a twofolddemographic problem: aging parishionersand a smaller contingent of millennialsapproaching middle age with a tenth ofthe wealth their parents had. Thatsituation is not likely to change when theirparents pass; aging is expensive.Practically, we must become a church ofthe poor for our survival because povertyis our future. More than that, the Churchcannot show Christ’s love to the woundedif it refuses to see them. Perhaps youngerpeople have not drifted away because of the evils of the secular world and how funthey are. Rather, God is love, and theChurch has not loved young people. Ofcourse they’ve fallen away. That’s what I was originally going to say.And then the coronavirus pandemic hit. I think older Americans are still in denial.As I am writing this, at least one memberof 20% of U.S. households has been laidoff. Some projections say we’ll have 30%unemployment by May. That exceedsGreat Depression unemployment figuresand creeps into Weimar Republic territory.Conservative projections estimate tens ofthousands dead in this country, mostlyamong the elderly. The cost of the 2008recession fell disproportionately on theyoung. That will not be the case for thisone. We are now, or will be very shortly, all inthis together in a way we weren’t before.The challenge is no longer asking churchleadership to acknowledge the poverty ofmy generation in preparation for a future,darker time when Millennial poverty is thenorm. That future has arrived. The already

0 9 T H E H O U Rincredibly stratified income and wealthdisparities will be blown even furtherapart. Nearly all of us will be on the poorerside of that divide. Class strife is not a new problem for theChurch. Communion in the early Churchwas a meal; both a sacrament and meansof making sure everyone ate. Paul is veryclear in his first letter to the Corinthians: acommunion where the rich don’t sharetheir food with others is no communion.His warning not to take communion in anunworthy manner (and thus divide thebody of Christ) directly follows hisreprimand of the rich.. It would be a verymyopic reading to suggest these twoadmonishments so close together havenothing to do with one another. Thecommunion of the Church is broken—Iwould argue has long been broken—bythe division between the rich and the poor.There never was a generation gap. It wasa wealth gap that our more affluentmembers dismissed as a generation gap.This framing allows them to ignore it. If there is a lesson to be learned from theaftermath of the Great Recession up tothe present day, it’s that people who arenot poor have every incentive to unseepoverty. Now, we all are about to becomevery poor. We will have a church dividedbetween those who don’t know wheretheir next meal is coming from and thosewho can afford to tithe. That second groupwill have undue influence. The Churchcannot serve both Jesus and money. Anyattempt to split the difference may, in theshort term, allow the current structure tosurvive. But it was built for a different timeand a different set of challenges and mustchange to meet the new ones. The poormust come first. I am, here, flirting with liberation theology,that darling of left-of-center AmericanChristians. American politics has been soconservative that the more radical aspectsof it are unlikely to be politicallyimplemented. That makes it, perhaps,seem like this safe, cuddly ideology; onethat makes us feel nice when it is front ofthe mind, but which can be put out ofmind quickly. It is plainly biblical, and sodifficult to disagree with. But outside ofGospel readings and general warmfuzzies towards the idea of economicjustice, the Episcopal Church is unlikely tocall wealth an outright sin and demand itsmembers give it up. That is a shamebecause Jesus made that exact demandseveral times. This is a way the Churchfails to love its members. If it is more

1 0 T H E H O U Rdifficult for a camel to get through the eyeof a needle than for a rich man to get intoheaven, if wealth imperils the soul, thenpussyfooting around that issue harms allof us. Again, we are about to become achurch of and for the poor. We can’tspend any time in this crisis coddling therich. We must serve the poor with teeth. If we fail to be an example of Christ’s lovethrough this crisis because we prioritizemoney over people, then the Church willnot die, but Anglicanism might. If we allowdivisions in the Church because of wealth,and worse, take the side of wealth, then Ifear we won’t meet the material needs ofour members and the wider community. Ifthat happens, many people will, rightly,say that Christ’s love lies elsewhere. Thatwould be a shame. There are ways to loveour neighbors that are hard to do withoutan infrastructure. I hope we will take thistime to reconsider the fundamentals ofhow we think and speak about poverty, aswell as implement structural changes tosafeguard against the undue influence ofwealth.M.K. AndersonAustin, Texas

1 1 T H E L E I S U R E O F A L L B E L I E V E R ST H E H O U RIn 1914, E.M. Green published a shortnovella called The Archbishop’s Test, inwhich a newly-elected Archbishop ofCanterbury, immediately faced with callsfor prayer book revision, instead suspendsthe work of not only the committees onprayer book revision but indeed all churchsocieties and auxiliary organizations tofocus instead on spending time with theresources they already have but do notuse. I am interested in this story less for whatsays about contemporary questions ofprayer book revision than what it sayswhat the clerical life should look like, andwhat a clerical life that foregrounds aparticular sort of leisure might have to sayto about the lives of the laity living in aworld governed by the workplacediscipline of late capitalism. In Green’s book, the Archbishop receivesa letter from an urban priest, who has hisconception of ministry turned upside downby the Archbishop’s directive: "The activity in this parish had been great.We had Church Lads Brigade, C.E.M.S.Clubs for every age and class, socialevenings, societies, guilds. The whole daywas occupied, and we priests rushed fromone thing to another, with little time tothink.…Now there is plenty of leisure, andyour Pastoral lays stress on prayer, but (itsounds a terrible thing to say) no one evertaught me to pray in the way I see nowthat one ought to pray. It is the same withthinking. There is plenty of time now tothink, but it is an art not learnt in a daywhen the rush of a lifetime has driven itout."

1 2 T H E H O U RThe classical tradition of writing onpastoral ministry, one exemplified ably inour own Anglican context by MichaelRamsey’s The Christian Priest Today,foregrounds the clerical leisure whichGreen’s priest has discovered, one that isnot sloth but instead the freedom to be forand with God and neighbor. I suggest thatthis clerical leisure provides a sort of iconfor the priestly life that all Christians oughtto share -- and moreover that this life isonly possible for all of us beyondcapitalism, when we are finally freed fromthe discipline of wage labor to be for eachother and for God in a non-alienated way.Ramsey, in his little book of advice forordinands, emphasizes both the utternecessity of time spent in prayer and theflexibility that enables priests to adjusttheir plans to face moments of need. Thework of prayer, he writes, is simply acentral task of ordained ministry. Inprayer, the priest is “with God for thepeople, and...with the people in God’sstrength”, adoring and interceding in bothset times of devotion and throughout theentirety of one’s life of participation inJesus’ high-priestly ministry of prayer.Moreover, in a sermon on the ordinationGospel, he exhorts ordinands towards “analertness which is ready to meetemergencies and interruptions”: “Do notbe encumbered. Be ready to move, rapidly andunexpectedly.” A full, rigorously-maintained schedule is simplyincompatible with the duty of the priest toaccept gratefully whatever the will of Godputs in her path over the course of theday, Ramsey believes. Although he doesnot use this specific language, it is, I think,fair to say that Ramsey sees freedomenabled by leisure as the vital prerequisiteto the exercise of the ordained priesthood.To be a priest requires being free to bewith God and with people in whatever waythe day brings, both in hours spent onone’s knees in the sanctuary and in hoursspent providing care in Jesus’ name. Andthis means that the priestly life must becharacterized by leisure. Moreover, thisemphasis is hardly unique to Ramsey. It israther striking, given the reputation ofGeorge Herbert’s The Country Parson formaking herculean demands upon theclergy, how often he enjoins the priest tosimply stroll about town, interacting withhis parishioners wherever he finds them.No day full of back-to-back committeemeetings here! While Herbert’s account ofthe ministerial life is certainly taxing, it isfar from over-scheduled. Consider as wellthe traditional use of the term living ratherthan salary for the material support givenclergy by the church. This suggests thatclergy pay is not wages for services

1 3 T H E H O U Rrendered so much as support which freesclergy from the necessity of supportingthemselves to be available as arepresentative of the Church to God, tochurch members, and to the world. Thatis, the life of the priest on this model isone of being set apart from wage laborand the particular demands of efficiencyand structure which accompany it in orderto be free to pray and to be alert to Godand humanity. But what does any of this have to do withthe life of ordinary lay Christians, who arenot in the same manner freed fromsupporting themselves with wage labor?Ramsey is again helpful here. He setsforth a conception of the ordainedpriesthood as “a gathering up of roleswhich belong to the whole church,”including “displaying” the priestly life of thewhole church in being publicly set asidefor service to Christ. That is, we shouldsee clearly in the priest what we perhapscan only see ambiguously in lives in theworkaday world: that Jesus’ total claimover our lives evokes a total response -and indeed a priestly response of beingwith God for the world, and with the worldfor God. Now, until Christ returns in glory,the Church will continue to set asideindividuals to be ordained priests to berepresentatives of both Christ and the Church in their particular ways. The needfor reproduction likely means that someChristians will need to spend more of theirtime in other forms of activity than prayer,study, worship, and works of service. Notall are called to religious life. However,Ramsey is keen to stress that the life ofevery Christian is a priestly one, and thatthe particular charisms of the ordainedpriesthood are ordered towards theupbuilding of the collective priesthood ofthe body of Christ. And thus if it isprecisely freedom from wage labor and itsdisciplines which enables the ordainedpriest to fulfill her priestly role, might notshe show us how a world without wagelabor would enable all of us to more fullylive as priests before God and neighbor? I think here of Marx’s famous line in theGerman Ideology about the unalienatedhuman under communism hunting in themorning, fishing in the afternoon, andphilosophizing in the evening. While I amnot convinced that socialism willnecessarily reject specialization or thedivision of socially-necessary labor in themanner which Marx here seems tosuggest, I think he gets at somethingcrucial about the shape of life weChristians must demand in a post-capitalist society: the freedom for variouskinds of activities within the whole course

of life of the human person, not merelyduring “time off” or weekends orretirement. The "leisure" of a priestly lifehelps us see how the discipline ofcapitalist labor works against faithfulChristian discipleship. Such a life limitsour freedom to be with and for God andpeople in the way to which our commonpriestly identity calls us, whatever othervocations we might have to particularlabors. For example, the hourly workercannot generally take time out of herworking day to pray or to attend to a friend(or stranger!) in crisis, even if her work isnot particularly socially necessary, outsideof the rare mandated "break." It alsoshows us a glimpse of what a future Benjamin CrosbyNew Haven, Connecticutof unalienated labor for us all might looklike, wherein rather than subjecting ahuge proportion of our waking hours to amode of life which often prevents us frommost fully fulfilling our shared priestlyvocation, we might support each other inour needs so that we can be available forthe work necessary to sustain ourcommon life, for our neighbors in need,and above all for God’s call. That is, if weaffirm - as we must - the priesthood of allbelievers, we must struggle for the leisureof all believers in a life beyond the wagesystem, because the leisure of thesanctified shows us the freedom which isthe necessary condition of the Christianministry we all share.1 4 T H E H O U R

1 5 W A K E T O S L E E PT H E H O U REight years ago I was in my second yearof a PhD program, and I was dying. It had been a long time coming. I was yourclassic overachieving grad student,trained from high school in the severedisciplines of maximizing intellectual work.I learned to read in mid-mornings, whenmy brain was attentive, and to attacklanguage study late at night, when it wassupple. I learned to chew on the inside ofmy lip until it swelled and grew ragged, tostay awake during lectures. I learned towrite a fifteen page essay in a singlesitting, ignoring my exhaustion, driven bychocolate-covered espresso beans and bythe rapture of seeing a complex argumentcome together on the screen in front ofme. I learned that my limits were farbeyond what my teachers expected themto be, and I learned to prize the respectand praise that came my way when Ishowed off what I could do. For whatever reason—being in a long-distance marriage, being in a programwhere students were treated as arenewable resource to burn through, orjust being in my early 20s, when manyserious mental illnesses hit in full force—by 2011 I was fantasizing every day aboutkilling myself. This would have worried memuch less if I were still able to work; but Isimply couldn’t concentrate. The charmingintricacies of cuneiform stood no chanceagainst the shame and self-disgust thaturged me to jump off a high rooftop. Evenworse, I had forgotten why I cared aboutthe work. I remembered that I had loved it,but most days I no longer rememberedwhy. My days passed in alternating agonyand fog. I spent a long time, at this period, in astate of profound helplessness. I went onmedical leave from my university, andthen left the program when my leave ranout and my sickness remained. I appliedfor jobs, unsuccessfully; I worked for sixweeks at Starbucks, but was unable tomaintain the pace. I signed up online as atutor but could neither hustle for newclients nor keep the few appointments Ihad. I could get myself to therapy, and Icould get myself to church, and that wasit. I was as useless as a broken pot.

1 6 T H E H O U RI think, in the long run, this helplessnesswas the greatest of God’s many gifts tome during this time. I had simply becometoo sick to maintain the illusion thatanything I owned was earned; I hadbecome too vulnerable to imagine I wascapable of protecting myself from povertyand the loss of everything I valued. I waslearning, in other words, what it meant tobe part of God’s creation. And aspromised, I discovered that this was verygood. How can I describe the strange joy ofdiscovering that my worth in God’s eyeshad nothing to do with my ability to work?Many people find their ability toexperience beauty compromised indepression; my response to beauty wasmagnified out of all reason. I wept atsunsets and small kindnesses; I laughedout loud at the silliness of children and theironies of fate; I took refuge in everychurch service I could, and when I sang inthe choir I felt as refreshed as a long colddrink of water on a thirsty day. One of the long-term effects of this time isthat my capacity for work remains greatlydiminished. I cannot survive without atleast one full day of rest each week. WhenI try (and I do, still) to push my limits, I am plunged quickly into a dark and churningsea of exhaustion and melancholy. I amstuck with the Sabbath; and this also isvery good. In the early church, the Sabbath cameunder the same suspicion as the otherdistinctive Judean ritual practices ofcircumcision and observance of Leviticaldietary laws. As Christianity expandedbeyond its origins in the Judaism of thesecond temple period, it emerged as acategory of identity which participated inethnic, philosophical, and devotionalboundaries in a new way. Early Christianwriters grappled with how to understandthemselves over and against other kindsof group allegiance, and one of the waysthey did this was to rely on rhetoricalconstructions of Jews as a foil for theirown self-definition. “We know that we areChristians, because we do not do thingsthe ways the Jews do.” Thus Justin Martyrgroups the Sabbath, together withcircumcision and dietary laws, ascommandments given to the Jews onaccount of (so Justin argues) their greatsins rather than as a gift in itself: “For we[Christians] too would observe the fleshlycircumcision, and the Sabbaths…if we didnot know for what reason they wereenjoined you—namely, on account of your

1 7 T H E H O U Rtransgressions and the hardness of yourhearts.” (Ante-Nicene Fathers 203) And so, as with circumcision and dietarylaws, keeping the seventh-day Sabbathfell by the wayside, broadly speaking.Ignatius replaces the seventh-daySabbath with observance on Sunday ofthe Lord’s Day, and exhorts theMagnesians to “no longer keep theSabbath after the Jewish manner, andrejoice in days of idleness, for ‘he thatdoes not work, let him not eat’….But letevery one of the you keep the Sabbathafter a spiritual manner, rejoicing inmeditation on the law, not in relaxation ofthe body.” (62) True Sabbath-keeping, forIgnatius, is to be found in the inclination ofthe spirit, not in the disposition of thebody. The rest and refreshment whichGod commands must be held distinct fromidleness and laziness; we can, if we havethe will to, observe the true Sabbath at alltimes. And the weekly celebration whichwe are called to is the eighth day, the dayof resurrection. Sunday sabbath for the Christian thus issomething both more and less than thebiblical sabbath. The Sabbath is a daywhen time explodes and collapses like adying star. In a sense which is true and also mysterious, it is the very day of theresurrection. It is also the day of theeschaton, a day when Jesus returns indreadful glory. Such a Sabbath offers us aweekly glimpse of being caught up withJesus into God’s own life. Yet we, like the writers of the earlychurch, exist in a culture which does notknow how to envision rest as a good initself. In many parts of the world, at manytimes, Sabbath has come to mean, atmost, going to church for an hour (andGod forbid the service go over time andmake us late for our brunch reservation!).Christian efforts to renew sabbathpractices often borrow from contemporaryJewish theology without acknowledgingthe ugly anti-Jewish rhetoric which led toits abandonment as a mandatory practicein the first place. I struggle to articulate what exactly islacking in Christian observance of theSabbath, and I hesitate to go head tohead with the saints of the early church,Yet I find myself longing for the simplecommandment to sit down and rest. Iconfess I look askance at Ignatius, whocondemns those of us who might rejoicein the body’s relaxation.

For me the breathtaking audacity of thesabbath lies precisely in its commandmentto be idle. I do not rest on the Sabbath forpurposes of self-care, though care for theself is good and right. I do not rest on theSabbath because periodic rest increasesmy ultimate capacity to work, although itdoes. I rest because God rested. I rest toremind myself that I am a creature, andnot the Creator; I rest to remind myselfthat to God my worth and my usefulnessare wholly different things. The Son of Man might have dominionover the Sabbath, but we do not. We arecreatures of God, and every moment ofour existence owes itself to God’scontinuing grace. If we cannot learn thison our own, perhaps we might rediscoverthe gift that a commandment can be. Mary DavisNew Haven, Connecticut 1 8 T H E H O U R

1 9 I N S P I R I T A N D T R U T H :T H E S O C I A L C H A R A C T E R O F T H E E U C H A R I S TT H E H O U ROriginally, this issue of The Hour wasgoing to extend the themes of the firstissue. In our focus on the Daily Office, thatissue observed that one must activelyprioritize the spiritual life in order for thereto be “room” for prayer; that priests haveto examine the demands of parish ministryand organize them in such a way that theycan place prayer -- especially publicprayer -- at the center of their vocation.This led us to ask the question of clergytime in relation to capitalism: if priests feelthey do not have the time to pray, or feel itis not important for how they minister, howis this being determined by the largersocial and economic contexts? Who istelling them, who is “making” them,organize their time according to metrics ofefficiency? And so we went about interrogating theeffects of neoliberalism on the pastoralvocation. The central commitment thatdrove our work was the conviction that“busyness” and “productivity” multipliesthe emotional and administrative tasks ofour ministers. Prayer, theological andbiblical study, continuing education --none of these can be shown to be “productive.” They do not give anyconcrete measures by which we mayjudge “success.” They certainly don’t“grow the church” or “bring in families andyoung people.” There is nothing of what we, the editors,originally wrote for this second issue thatwe would wish to change. However thetheme of the issue, and the bulk of thekeynote essays, were arranged before thefull onset of COVID-19 made itself felt inour church. All of a sudden it seemedpetty to take aim at the total cost ofSunday bulletins when our people havebeen forced to refrain from partaking inthe sacraments. As our parishes scrambleto find ways to connect, the last thingpriests need is a scolding about how theyuse their time. And yet a crisis such as this is exactlywhen those committed to “take their sharein the councils of the Church” need tohave tools at their disposal to explain ourreceived practices. One issue in particularhas presented itself in earnest, and weare desperately in need of clarity on thematter: namely, the “virtual” consecration

2 0 T H E H O U Rof the elements of the Holy Eucharist fromafar, with the intent that people might beable to share in the grace of the Body andBlood of Christ in their homes. Themassive, instantaneous growth of onlinemeetings in response to the coronavirushas the potential to shift our ecclesialpractices long-term, well beyond theimmediate circumstances that havenecessitated their onset. As a short-term response to anexceptional time, there seems to benothing wrong in live-streaming worshipservices. Indeed, there may even beopportunities for the Church to learn andgrow right now. Digital connection can bea genuine good for the aged and disabled,and we should prayerfully explore howwhat we do now can be integrated intochurch life going forward. But the veryidea of the sacraments is at stake in thequestion as to virtual consecration, as wellas the passive viewing of the Mass athome. If we were to grant that peoplecould have wine and bread at homeconsecrated by their priest over theinternet, there is nothing, logicallyspeaking, to prevent us from getting rid ofpriests entirely and having, say, a singlebishop digitally consecrate elements fordispersed individuals, families, and living room groups. And there are so manysecondary matters that immediatelypresent themselves. The consecratedelements cannot be disposed of in anyway that seems fit. How are we to ensurethat extra bread and wine is reverentlyconsumed and not merely tossed out?And so on and so forth. This is not mere clericalism here; a cabalof power-thirsty hierarchs concerned tomaintain a position of spiritual power overa mass of laity. Our practices do not cometo us in isolation, as a mere rite in a bookjust before us. There is a material historythat has brought us to where we are, andthere is a logic that keeps us fromdevolving to simple Zwinglianism. There isnot space in this essay to give anexplanation of every aspect ofecclesiastical polity, and all would berichly rewarded to read Richard Hookeron the matter anyway. The powerfulinsights of our greatest post-Reformationdivine should be commended to all onwhy bishops, why buildings, whycorporate prayers. For the current push bysome -- if even a minority -- to do awaywith these things manages to sound anawful lot like the iconoclasm of thePuritans that he so nobly combatted.

2 1 T H E H O U RBut many defenses of the necessity of aphysically-gathered body for the Eucharistfall short of serious insights. For instance,it simply is not true that “online”friendships “aren’t real.” This magazinewas itself started by two friends who havenever met “in real life,” but who havemanaged to be truly enriched by theirrelationship. It may be that we also need“physical” friendships for a healthy soul,but that doesn’t detract from the reality ofonline fellowship. Likewise appeals to “incarnation” or“materiality” get at something true, but onaccount of their abstract character, areunable to become full-fledged articulationsof why we must celebrate the Eucharist inperson. It is not enough to point to thename of a doctrine as if the appeal aloneis sufficient to establish the argument,without spelling out the shape of the logicinherent in the doctrine. Thankfully for us,the Incarnation has been deeply exploredthroughout the history of Anglicansocialism, and if one wanted to ground thesacraments in the Incarnation, one coulddo much worse than turn to the Lux Mundischool and her children. But this essay will not use the Incarnationfor its argument, though it could be enhanced by connecting it with thatcentral truth of the Christian faith. For theIncarnation of the Word of God is that onwhich every other doctrine hangs, andwithout which we may as well shutter allour windows, and turn our buildings intohair salons. Neither will it rely on thatstaple of modern Anglicanism that is“liturgical theology.” If we didn’t know thisbefore, surely we know now -- on thebrink of yet another global economiccollapse -- that no liturgy, howeverdivinely constructed, however perfectlyrehearsed, can by its own performancedeliver us from the principalities andpowers now prepared to slay millions onthe altar of the Dow Jones. Some who would want to defend theEucharist take their stand on “community.”The idea being that the church exists tocurate a voluntary association of affectiverelationships. No online interactions,however real, can adequately address ourneed for such “embodied” relationships.While this at first seems a good route totake, it is a dead end. It only makes sensefor those who think of “religion” in purelysociological categories, where “religion”serves a social “function.” Humans “need”community, and religions supply thatneed. This assumption is plainly an

anthropological etiology, reverse-engineering for the existence of “religion”as a phenomenon. It is a term alreadydefined in advance. On this scheme,religions exist to give structure and shapean individual’s “experience” of “the divine”(however one wants to understand thatphrase) and to allow for a measure ofbroader social cohesion. But if one’s“connection to the divine” can be as easilymet through a screen as in a nave, thereis no reason why one could not supplycommunity through their already-existingnetworks of friends, family, andcoworkers. Indeed, they already do, andtheir friends don’t ask for a priest with astipend, or a sanctuary with a mortgage.The days are coming and are alreadyhere, when this relic of 19th centuryanglo-american philosophy of religion willpass away, and nobody will feel thecultural pressure to connect their“experience of the holy” with their socialcommunity. It can remain in the pureinteriority of each person, where itbelongs. What we need, therefore, is anexplanation of the inherently socialcharacter of the Holy Eucharist. It ishoped that in showing it, we as a Churchmight have more substantial resources fordefending the belief that the Eucharistic elements cannot be thought orperformed in physical isolation. Becausethe Lord’s Supper is not simply a vehiclefor invisible grace, but the effective sign ofour entire ecclesial existence. “Our fathers worshiped on this mountain;and you say that in Jerusalem is the placewhere men ought to worship." Jesus saidto her, "Woman, believe me, the hour iscoming when neither on this mountain norin Jerusalem will you worship the Father.You worship what you do not know; weworship what we know, for salvation isfrom the Jews. But the hour is coming,and now is, when the true worshipers willworship the Father in spirit and truth, forsuch the Father seeks to worship him.God is spirit, and those who worship himmust worship in spirit and truth." This famous passage is sometimesinvoked in discussions about whether theChurch “needs buildings”, and has beenused by some to legitimize virtualconsecration. The passage is understoodto mean that locality is irrelevant when it 2 2 T H E H O U R

2 3 T H E H O U Rcomes to worship. Worship can happenanywhere. And since the grace conferredin worship is commonly conflated with“experiencing the Spirit," there should benothing that stands in the way of anyoneencountering God on their own terms. TheChurch isn’t the building anyway, it is said;it’s “the people.” This last point is certainly true as far as itgoes. The Church is not a building, and inthat sense is not ultimately dependent ona specific shelter in order to exist. St. Paulsays “Do you not know that you are God’stemple and that God’s Spirit dwells inyou? (1Cor 3.16),” and the Psalms alsowitness to this truth: “When Israel cameout of Egypt, the house of Jacob from apeople of strange speech, Judah becameGod’s sanctuary and Israel his dominion(114.1-2).” But the passage in questionisn’t about geography or buildings somuch as corporate election andlegitimacy. In our rush to wring essential truths fromparticularized passages, we oftenoverlook the larger contexts of the biblicalwitness. St. Photine, our “woman at thewell,” is a Samaritan. And the Samaritanswere members of Israel. In the book ofKings, the united kingdom of Israel rapidlydivides after Solomon into the northern Kingdom of Israel, and the southernKingdom of Judah. The monarchs ofnorthern Israel by and large reject the soleworship of YHWH and do notacknowledge the temple of Jerusalem tobe the only legitimate place to offersacrifice to the LORD. According to thebiblical witness, in response to thisinfidelity, and at the behest of the LORD,Israel is conquered by the Assyrians andmany of its people are sent into exile.Those left behind apparently stayed in theland -- albeit as participants in a vassalstate under Assyrian control -- or fled toJerusalem. But even in the first century,Samaritans worshiped on Mt. Gerizim andhad their own Samaritan Torah. The Kingdom of Judah managed to evadedestruction for two centuries after Israelhad fallen, but it too eventually wasdefeated by the Babylonians, and itsruling classes exiled. This gap of twocenturies between exiles, however, wasunderstood by the southern Kingdom tobe a verdict in favor of the sole legitimacyof the Temple of Jerusalem. This beliefmanaged to continue well after Judah’sown destruction, and the literature of thesecond Temple period is unshaking in itssupersessionism. Though Ezra andNehemiah show strong examples of this

2 4 T H E H O U Rtendency, perhaps nowhere is it foundmore clearly than in Psalm 78.67-69: “The LORD rejected the tent of Josephand did not choose the tribe of Ephraim;he chose instead Mount Zion, which heloved. He built his sanctuary like theheights of heaven, like the earth which hefounded forever.” So when the Woman at the Wellchallenges the idea that Samaritanworship is invalid, she is not making apoint about “material” worship, so thatJesus can tell her about “immaterial”worship. She is not saying God is“confined” or “limited” to one spot. She isquestioning the authority of Judeans tohave declared the LORD’s covenant withthem void. Do the Samaritans not have atemple? Do they not have the Torah? Arethey not the people of Israel? But what of Jesus’ reply? There are twoimportant aspects to keep in mind. Thefirst is Jesus’ prophecies concerning thetemple of Jerusalem. This enactedparable of the Temple’s comingdestruction manages to find its way into allfour canonical Gospels. The centrality ofthe incident cannot be overstated. WhileJohn seems to place it at a different pointin Jesus’ public career than in theSynoptics, it is still there. Moreover thejustification given for driving the moneychangers out is the same for all. Drawingdirectly on the prophecies of Jeremiah,Jesus condemns the temple because theJudean poor are oppressed and trueworship of God is thus obscured. By thetime Jesus visits Samaria in chapter 4, hehas already predicted the Temple’sdestruction. John tells us in an editorialaside that “the temple of [Jesus’] body”will be raised, and this resurrection is asign of the authority he has to perform theprophetic action. But the Temple of Jesus’Body, the Body of Jesus the Anointed,after Pentecost, is an irreducibly socialbody, a corporate phenomenon, a visibleChurch, a renewed and reunited people ofIsrael. Jesus, in choosing twelve disciples,gives us a sign that the Northern Kingdomis not excluded from his own work. Godhas not rejected Joseph and Ephraim, buthas reunited them to Judah in his ownflesh. Yes, Jerusalem will no longer serveas the exclusive site for authentic worship,but this is not because God has givenindividuals the ability to go it on their own;rather it is because the Temple is his fleshgiven for the life of the world, the blessedBody and Blood of Jesus, which is at oneand the same time the Church itself --

Israel and the Gentiles he has included --and the Holy Eucharist. Christ is bothpriest and sacrifice; so also is the Churchboth a kingdom of priests, and theoffering: All things come from Christ, andof Christ’s own do we give in the sacrificeof the Mass. This is made clearer by a closer look at“spirit” and “truth” in the Fourth Gospel.Again Jesus is not making a point aboutmystical truths and immaterial worship.The opening prologue of John’s Gospeltells us that Jesus is “full of grace andtruth (1.14;17).” St. John the Baptisttestifies to the truth of Jesus’ witness(5.33). Jesus not only tells the truth (8.40;44; 45; 46), but is himself the Truth (14.6).Jesus’ disciples are those who follow hiswords. They will know the truth, and beset free by it (8.32). They are to besanctified and consecrated in truth (17.17;19). Moreover the Spirit is the Spirit ofTruth (14.17; 15.26; 16.13). It will glorifyJesus and will lead Jesus’ disciples into alltruth (16.14). The most dramatic story about truth inJohn is found in chapter 18, when Jesusis brought before Pilate. In the course ofbeing questioned about whether he is theKing of the Judeans, Jesus says: “For thisI was born, and for this I have come intothe world, to bear witness to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears myvoice (18.37).” To which Pilate respondscynically, “What is truth?” Normally, it is not a particularly reliableinterpretive method to rely overmuch on alexicon. The meaning of words is derivedfrom their use as much in Koine as inEnglish. But I bring together theseincidents of “spirit” and “truth” in John in ahighly compressed form because theFourth Gospel intentionally repeats keywords and tropes to develop itstheological points. In John, God theFather’s identity is not easily known: “Noone has seen God at any time” thePrologue tells us, “but the only unique onein the bosom of the Father has made himknown.” Jesus reveals the Father. Sowhen Jesus says that we will worship Godin spirit and in truth, we must see that thismeans nothing less than worshiping bymeans of the same Spirit he breathes onthe disciples (20.22). To worship God in “spirit” and “truth,”then, is not about bucking a religiousestablishment, it’s not about getting rid ofbuildings, even less is it about isolatingthe sacraments from the gathered Body.It’s about the revelation of the God ofIsrael through Jesus in the people heconstitutes in his Body. 2 5T H E H O U R

“ "When you come together, it is not reallyto eat the Lord’s supper. For when thetime comes to eat, each of you goesahead with your own supper, and onegoes hungry and another becomes drunk.What! Do you not have homes to eat anddrink in? Or do you show contempt for thechurch of God and humiliate those whohave nothing?” First Corinthians 11:18-34 is something ofa locus classicus for establishing therewas a relationship in the early churchbetween class politics and the Eucharist.Written decades before Luke told us aboutthe communism of the Jerusalemassembly, here St. Paul stridentlychastises the Corinthians for intra-ecclesial factions that fell along classlines. The picture is stark: Some devourfor themselves the church’s commonmeal, leaving others hungry who werecounting on it. In doing this those whohave enough to eat at home fail to“discern the body” and eat and drinkGod’s judgment upon themselves.It’s telling that Paul moves immediatelyinto a discussion of the nature of the bodythey are to discern. Chapter 11 clearlyenough tells us that the communal meal,set apart for this specific function, is thebody of Christ. But Paul also tells them inthe next section that they, the Corinthiansthemselves, are the body of Christ(12:27). There is no clear delineationbetween the body of Christ as theEucharist and as the Church. The meal isproduced by the Church and for theChurch, and yet the meal in a sense“creates” the Church in being made intoan effective sign, a (re)presentation ofitself, to itself. The body is at the sametime the one and the many. In the form ofbread and wine it is one until distributed,and in being distributed to all, becomesone again. But the body cannot even beone without being also the many: “The point of [12.15-21] is not that thedifferent members must be united amongthemselves…but precisely that there mustbe more than one member if there is to bea body at all.” (JAT Robinson, The Body:A Study in Pauline Theology. SCM Press,1961. pg.59) 2 6T H E H O U R

Failure to facilitate a life sufficient to all thechurch is a failure in that it prevents thefullness of the Spirit’s life to be offered forthe sake of all. Each member hasreceived unique gifts, of which every othermember has need. No one can say theydo not have need of any other (12.21) andno one can claim they don’t belong to theothers (12.15-20). This solidarity is inexcess even of a local gathering andextends to the whole international body. InPaul’s second letter to the Corinthians hespeaks about the collection being takenfor the church in Jerusalem. Using theexample of Christ’s self-offering (II Cor8.9), Paul exhorts them, saying he has nointention of impoverishing them, but “relieffor others...follows from equality. At thepresent juncture, your abundance is fortheir lack, so that their abundance may befor your lack, in order that there might beequality.” (8.13-14, David Bentley Hart’stranslation. YUP, 2017) Notice there is no differentiation between“spiritual” gifts and “material” gifts. All giftsare in fact “spiritual” in that they havebeen given by God’s Spirit. Thus thematerial excess of Paul’s churches can begiven away because giving is itself anoperation of the body for itself. But so long as the material well being ofany assembly is compromised, theChurch is not being sufficientlydispossessive. Jerusalem is not the onlyone that “lacks,”. The mere fact that theCorinthians have more than enough is inreality their own lack, which they can fillup only by giving away. This is how we must take the words ofOur Lady in the Magnificat, “the rich hehas sent away empty.” So often the imagewe have of this passage is of the richbeing turned away in bitterdisillusionment, condemned to live withwhat they already had, and doomed to theinsularity of their private estates, shut outfrom the life Jesus makes possible. Andcertainly Jesus - especially in Luke - isunambiguous that as it stands, the richcannot inherit the life of the age, even if“all things are possible with God.” Insteadwe can imagine the rich coming beforeJesus and receiving everything in the onlyway it had ever been possible - by havingit taken away from them. The discussionabout virtual consecration deals only inabstractions when it becomes a questionof “powers” granted to priests rather thanlaity; about what is “valid;” or aboutwhether online fellowship is “real or not.” 2 7T H E H O U R

Rather, as these and so many scripturalpassages indicate, the eucharisticelements simply dissolve intomeaninglessness when isolated from thegathering of mutual support, of giving andreceiving, both material and spiritual thatconstitutes the life of the Church, thatbody that is never fully free or substantialso long as a single member lacks breadand wine. Tony HuntMinneapolis, Minnesota 2 8T H E H O U R

2 9 P E R C Y D E A R M E R : L I T U R G I S T A N DS O C I A L I S TT H E H O U RPercival Dearmer was a priest in theChurch of England, and longtime vicar ofSt. Mary the Virgin, Primrose Hill. Born in1867, and ordained in 1892, Dearmer isbest known for his work in mattersliturgical. Justly famous for the Parson'sHandbook, he wrote extensively about thehistory of the English prayer books and ofworship on the Island more broadly. Beingan anglo-catholic, he was sympathetic tothe priests at the center of the ritualistcontroversies, however he did not like theway contemporary roman practices wereadopted by them. Dearmer preferred tofind an "English" catholic tradition to drawon that predated the liturgies being usedby the slum ritualists. He found this in the"Sarum Rite" and he worked to utilize theSarum liturgies while remaining in fullconformity to the rubrics of the 1662 BCPhe was required to use as vicar.Eventually he would contribute to severalproposed prayer books in England aheadof the doomed proposed 1928 BCP,teaming up with the likes of Charles Goreand William Temple. Dearmer collaborated with the famous Ralph Vaughan Williams to create theEnglish Hymnal and the Oxford Book ofCarols. These too continued his project ofdiscovering and encouraging the use oflocal styles for English services. Heloathed the popular Victorian hymns asbawdy and "germanic." With Williams andothers he unearthed a host of old folksongs and carols. These efforts made asignificant contribution to English sacredmusic even to the present day. He was also a socialist. Williams tells this charming story aboutwhen he was first approached byDearmer: "It must have been in 1904 that I wassitting in my study in Barton Street,Westminster, when a cab drove up to thedoor and ‘Mr. Dearmer’ was announced. Ijust knew his name vaguely as a parsonwho invited tramps to sleep in hisdrawing-room; but he had not come tosee me about tramps. He went straight tothe point and asked me to edit the musicof a hymn book."

3 0 T H E H O U RIt wasn't enough for him to attempt reformin liturgical matters, as if this was separatefrom his political convictions. To that end,he formed the Warham Guild in order tofurnish high quality ornaments andvestments for churches and clergy,produced with fair labor conditions. He was secretary for the Christian SocialUnion, the more mainstream Anglicansocialist group of the time. A talentedwriter, he composed various tracts for thelikes of the Fabians and Papers For WarTime. Dearmer's fire for reform did not dimas he aged. In his later years he helpedorganize and lead unofficial churchgatherings at which Maude Royden-Shaw,a suffragist and advocate for women'sordination, preached. We present here two pieces of his. Thefirst is a Litany of Labour, which wasincluded in the prayer book drafts hecontributed to. It can also be found in hislittle book The Sanctuary, an excellentmanual of devotion for communicants. The second is a long tract for the FabianSociety in which he explores a theologicaljustification for why Christians must besocialists.They are presented unedited, though theydisplay the casual supersessionismtypical of the time, along with somestereotypical Christian portrayals of thePharisees in the Gospels. But the point ofincluding historical sources in The Hour isso that we can all become familiar withour substantial, long-standing tradition.You can't critique or develop a trajectoryyou don't know. The Fabian tract is arepresentative piece that gives us tinyglimpses into positions common for thetime. It opens with a quote from F.D.Maurice, considered the godfather ofAnglican socialism; it shows evidence ofsympathetic familiarity with Marx; it leansheavily on the Gospel of Luke, especiallythe Magnificat; it attempts to groundChristian socialism in Scripture, withspecial attention to passages authoritativefor Anglicans, such as the Lord's Prayer,used in catechesis; the Epistle of Jameswas a key text for the Anglican socialists,and Dearmer quotes from it as well. The tract is fearless. I was struck on myfirst reading by the boldness of its moralvision. May we become so sure in ourfaith that we would take similar risks in ourteaching, our preaching, our actions.

For public use, it is best that each Part shouldbe taken bay a different reader. The Litanycan be shortened by the omission of Parts IV,or II, or of both. ILord have mercy upon usChrist have mercy upon usLord have mercy upon us O God the Father of All, Have mercy upon us. O God the Son, Redeemer of the World, Have mercy upon us. O God the Holy Ghost, dwelling in men, Have mercy upon us. O Holy Trinity, one God, Have mercy upon us. II Jesus, born in povertyborn to bring peace among men,workman at Nazareth,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, in whom the proud were scatteredand the mighty put down,giving good things to the hungry,exalting them of low degree,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, who fillest the valleys and levelestthe hills,in whom every human thing is holy andprecious,who hast taken all humanity into thyself,Have mercy upon us. 3 1

Jesus, in whom all the nations of the earth areone, in whom is neither bond nor free, Brother of all,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, preaching good tidings to the poor,proclaiming release to the captives, setting atliberty them that are bruised,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, friend of the poor, Feeder of thehungry, Healer of the sick,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, Lord of health, Vanquisher of earlydeath, Lover of little children,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, denouncing the oppressor, instructingthe simple, going about to do good,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, teacher of patience, pattern ofgentleness, prophet of the Kingdom ofHeaven,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, tempted like us, constant in prayer,companion of the outcast,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, hater of hypocrisy, enemy ofMammon, stay of the humble,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, forgiving them that love much,drawing all men unto thee, calling themthat labour and are heavy laden,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, who camest not to be ministeredunto, but to minister, who hadst not whereto lay thy head, loved by the commonpeople,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, betrayed for the sake ofmoney,Taken by the chief priests,Condemned by the rulers,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, crucified for us,Have mercy upon us. Jesus, who hast called us to the fellowshipof thy Kingdom, in whom is no respect ofpersons, who wilt know us by our fruits,Have mercy upon us. Thou Voice of Justice, who dost say to us:‘Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one ofthe least of these my bretheren, ye havedone it unto me,’Have mercy upon us. III From the love of money,Good Lord, deliver us.From dishonesty in business,Good Lord, deliver us.From forgetfulness of our duty,Good Lord, deliver us. 3 2

From anger and malice against opponents,Good Lord, deliver us.From neglect of labour,Good Lord, deliver us.From contempt for others,Good Lord, deliver us.From offence against thy little ones,Good Lord, deliver us.From oppression of the poor,Good Lord, deliver us.From envy of the rich,Good Lord, deliver us.From the acceptance of worldly standardsGood Lord, deliver us.From fear of proclaiming thy acceptable year,Good Lord, deliver us.From hardness, narrowness, and distrust,Good Lord, deliver us.From a weak will and unstable purpose,Good Lord, deliver us.From want of faith in the accomplishment ofthy will,Good Lord, deliver us. From all pride,Good Lord, deliver us.From all avarice,Good Lord, deliver us.From all lust,Good Lord, deliver us.From all anger,Good Lord, deliver us.From all gluttony,Good Lord, deliver us.From all envy,Good Lord, deliver us.From all sloth,Good Lord, deliver us.By thy taking of our flesh, By thy humble birth, By thy hard life, By thy bitter death, By thy glorious Resurrection and Ascension,Dear Lord, deliver us. IV Be merciful unto us.Hear us, Lord Jesus. By thy recovering of sight to the blind,Remove from us all prejudice. By thy teaching on the Mount,Teach us to hunger and thirst afterrighteousness. By thy miracle at Cana,Increase among us the joy of life. By thy parables about riches,Help us to distribute. By thy words to the Pharisees,Give us courage to rebuke the wrong inhigh places. By thy washing the Disciples’ feet,Teach us to serve others. By thy prayer on the Cross,Teach us to love our enemies. By thy Cross and Passion,Help us to suffer for the truth’s sake. 3 3

By thy presence in the Church,Keep us faithful to thy law of love. By thy prayer thou has given us, Help us to live more nearly as we pray. By thy prayer thou hast given us, Help us to do thy will upon earth. By thy life and teaching, Make us to love God before all things. By thy life and teaching, Make us to love our neighbour as ourself. V Finally, we beseech thee, O Lord, mightyand ever wise, that thou wilt guide,protect, and inspire all those who earn andlabour truly to get their own living. For men who face peril,We beseech thee. For women who suffer pain,We beseech thee. For those who till the earth, for those whotend machinery,We beseech thee. For those who strive on the deep waters, forthose who venture in far countries,We beseech thee. For those who work in offices andwarehouses, for those who labour at furnacesand in factories,We beseech thee. For those who toil in mines, for those whobuy and sell,We beseech thee. For those who keep house, for those whotrain children,We beseech thee. For all who live by strength of arm, for all wholive by cunning of hand,We beseech thee. For all who control, direct, or employ,We beseech thee. For all who enrich the common life throughart, and science, and learning,We beseech thee. For all who guide the common thought, aswriters or as teachers,We beseech thee. For all who may serve the common good aspastors, physicians, soldiers, lawyers,merchants, and for all social workers,leaders, and statesmen,We beseech thee. And for all those who are poor, and broken,and oppressed: 3 4

For all whose labour is without hope,For all whose labour is without honour,For all whose labour is without interest,For those who have too little leisure,For those who are underpaid,For those who oppress their employeesthrough love of money.For all women workers,For those who work in dangerous trades,For those who cannot find work,For those who will not work,For those who have no home,For prisoners and outcasts,For the victims of lust,For all who are sick or hungry,For all who are intemperate, luxurious, andcruel, Dear Lord, we pray to thee. O Lamb of God that takest away the sins of the world, Have mercy upon us.O Lamb of God that takest away the sins of the world, Receive our prayer. Lord have mercy upon us. Christ have mercy upon us.Lord have mercy upon us. Our Father. Let us pray :--- Collect. We pray, Father of all, who lovest all men, for anew England, a new Europe, a new Asia, and anew world, wherein every race may be free, andgovernment may be of the people, by all and forall; So that the Nations, ordering their stateswisely and worthily, may live in the example ofthy Son Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with theFather and the Holy Spirit, may all the praise ofthe world be given, all power, dominion andglory for ever. Amen. Or this Prayer. O Father of light and God of all truth, Purge thewhole world from all errors, abuses, corruptions,and sins. Beat down the standard of Satan, andset up everywhere the standard of Christ.Abolish the reign of sin, and establish thekingdom of grace in all hearts. Let humilitytriumph over pride and ambition: charity overhatred, envy, and malice; chastity andtemperance over lust and excess; meeknessover passion; disinterestedness and poverty ofspirit over covetousness and the love of thisperishing world. Let the Gospel of Christ, in faithand practice, prevail throughout the world;Through him who liveth and reigneth with theeand the Holy Ghost, one God world without end. Amen. The Grace.3 5

3 6

ETHHOURTHIS PUBLICATION REJECTS PROFIT.HOWEVER IT IS OUR DESIRE TO PAYOUR WRITERS AS MUCH AS WE CANAS SOON AS WE CAN. YEARLYTRANSPARENCY REPORTS WILL BEAVAILABLE THAT WILL SHARE HOWANY FUNDS RECEIVED WERE USED.CONSIDER SUBSCRIBING IF YOU CAN.TO SUPPORT, VISIT OUR PATREONPAGE OR DONATE ON PAYPAL THE EDITORS