Return to flip book view

ONE TWENTY-SEVEN First Edition by: Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team Dr. Andrea Siegel

Copyright © 2024 Helping Children Worldwide, Inc. 14101 Parke Long Ct, Chantilly, VA 20151 helpingchildrenworldwide.org With special recognition and thanks to: Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team All rights reserved. KDP ISBN for Amazon Purchased Books. 9798338194966 Please note if your purchase is genuinely from HCW-SRP listing when ordering through Amazon.

Dedicated to all those who are vulnerable, the "widow and the orphan" whoever and wherever you may be: your determination to survive with dignity is a source of profound inspiration to so many. And to our founders, Bishop John Yambasu, of blessed memory, and Bishop Tom Berlin.

PRAISE FOR ONE TWENTY-SEVEN “An inspiring and practical resource for believers seeking to deepen their understanding of God's heart for the vulnerable. This study beautifully weaves together the book of James and real-life applications, offering insights on how to care for orphans and build strong families. Perfect for small groups or individual reflection, this book empowers readers to live out their faith through compassionate action and family stewardship.” Rev. Barbara Miner, Executive Pastor Floris United Methodist Church, Reston, Virginia “A clear and deeply compelling call to heed the commandments in James 1:27, to look upon and care for the widow and orphan. It provides the critically important cultural and historical context for who the widow and orphan might actually be, to inform our own understanding today. The study leads us to let go of guilt-led responses and towards embracing a life that is aligned with the nature in which we were created. As an advocate for family-based solutions for orphaned and vulnerable children, I see this study as a powerful invitation to join the collective mission of Christ followers to see every child remain in, find, or return to a safe and loving family.” Elli Oswald, Executive Director Faith to Action, Seattle, Washington “James 1:27 is an often misunderstood verse. This study provides the rich historical context and careful scholarship to help Christians understand how we can live out our Biblical call to care for orphans. I highly recommend this study to churches who wish to go deeper in their understanding of God’s heart, and our responsibility, toward orphans and vulnerable children. “

Kristen Lowry, International Orphan Care Consultant Send Relief, Naivasha, Nakuru, Kenya “I enjoyed the piece quite a bit. It deeply resonates with where my head is right now, and how I framed my drash of the Binding of Isaac for Rosh HaShana morning. The writing is not too dense, but it is academic. I especially like the call to action in the last part." Rabbi Elizabeth Goldstein, Senior Rabbi Congregation Ner Shalom, Woodbridge, Virginia Go to the Helping Children Worldwide website to read published reviews or submit a review of the study. If you review on Amazon or Goodreads, you can use this form to send us a link to your review, so we can share with other!. https://www.helpingchildrenworldwide.org/one-twenty-seven-reviews.html

Table of Contents PRAISE FOR ONE TWENTY-SEVEN 4!PREFACE 7!A NOTE FROM HELPING CHILDREN WORLDWIDE 8!MELODY CURTISS, CEO 8!ABOUT THE COVER ART 11!HOW TO USE THE GUIDE 13!ONE TWENTY-SEVEN 21!INTRODUCTION: WHAT ARE WE TO DO? 23!FIRST READING 32!SECOND READING 40!THIRD READING 50!FOURTH READING 61!REFERENCES AND ENDNOTES 68!

Preface The material in this study guide can be used as a tool to facilitate discussions with the chapter materials. For the serious biblical scholar, you may also choose to dive deeper, through reading the rich materials in the references and resources in the endnotes. We want to thank all of those who contributed to make this valuable resource to share with members of the faith community. The body of the material was written by Dr. Andrea Siegel, with editorial review and contributions from the curriculum development team, including Dr. Laura Horvath, Yasmine Vaughan, MPH, and Dr. Melody Curtiss. We wish to acknowledge and thank those amazing leaders in the global child welfare sector and religious leaders who provided additional review and suggestions for improvements. The material is stronger because you cared enough to gift us your time and understanding of the scripture, the biblical to care, and underlying issues in the modern world.

8 A Note from Helping Children Worldwide Melody Curtiss, CEO Helping Children Worldwide (HCW) is a 501(c)(3) faith-based not-for-profit corporation, registered in Virginia, and licensed to solicit donations from all 50 states and the US territories. We are a Christian-faith institution, but not a church, although we are closely affiliated with The United Methodist Church. We work in an interfaith world, and we share our perspective without judgment as to other faith traditions with respect to employment, collaborations, and support of vulnerable children. Our mission is to help children worldwide by strengthening families and communities, and we operate entirely through collaborations, networks, and support of localized efforts. From HCW’s perspective James 1:27 is perhaps the most important passage in the New Testament. The spirit reflected in the words of James 1:27 is the reason that Helping Children Worldwide exists and is at the heart of the work we do every day. We reference it simply as 1:27. Many Christians recognize the number 3:16 is a reference to John 3:16. “For God so loved the world,” and a basic tenet of Christian faith. In James 1:27, we think you will find another key to God’s plan for the world. “Three Sixteen” expresses the depth of the love God feels for us as the reason he chose to send Jesus to teach us and redeem us. Rather than punish us for our failings, we are offered lessons, and provided the life and teachings of Jesus as the primer on how to live a righteous life. The study was primarily authored by Dr. Andrea Siegel, a biblical scholar who joined the staff of Helping Children Worldwide as a graduate intern during Covid, when we first opened our internships to remote participants. We were so blessed by her contributions that we asked her to return after graduation and join us on a mission team as a professional consultant. Dr. Siegel has remained a good friend and become a vital resource for our work ever since.

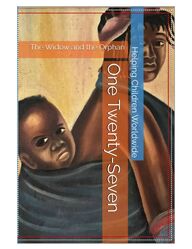

The Widow and the Orphan 9 We believe One Twenty-Seven removes any trace of doubt of exactly what we are expected to do in response. James 1 is 27 verses long and 1:27 is the very last verse of the first chapter of James. Whatever you believe, this study will be a great springboard for deep discussion and exploring those beliefs in the context of your life and the lives of others around you. Helping Children Worldwide commissioned the bible study as an adjunct resource for the Strong Family for Every Child campaign. While there are plenty of relevant passages, we find One Twenty-Seven to be the most concise and compelling biblical argument. As a matter of added satisfaction, we chose a painting that hangs in a place of honor in my home as the cover image. This painting is the work of a brilliant artist in Sierra Leone, West Africa, who many of our staff and volunteers know well, and whose works are featured on the walls of our international headquarters and in many homes of our volunteers, donors, and mission team members. If you ever travel with us to Bo, perhaps you can view his gallery, buy one of his original works, or even commission a painting. Dr. Siegel’s background in chaplaincy and social work, and experiences in Sierra Leone working as part of our curriculum development team have been instrumental in creating faith-based study materials developed to inform and educate orphan response ministries, including evidence-based family strengthening curriculum for deployment in low literacy environments, and interfaith workshops on initiating difficult conversations in international mission. Dr. Siegel holds a doctorate in Hebrew literature, a master’s in social work, and a clinical license as a psychotherapist. As a Jewish scholar of biblical literature, Dr. Siegel has a unique perspective on the time and place when James 1:27 was written and provides context that might otherwise be missed. She documented her research into the context and citations to sources can be found in the text of the study and in the extensive endnotes, for readers who wish to delve even deeper into the source materials. Faith leaders from several denominations and religions were invited to review the study and provide commentary; this included ordained ministers from the Christian faith and rabbis from the Jewish faith. Quotes from those who reviewed the study are included on the book jacket and the webpage where you can download an electronic copy. Many of the faith leaders deeply familiar with the gospel welcomed and expressed their appreciation for this deeper foundation and grounding in the context of the scripture passage. We hope that Dr. Siegel’s research and explanation will enrich your studies as well.

One Twenty-Seven 10 The staff of HCW piloted a portion of the study in September of 2024 as a discussion tool during a special meeting of our international mission collaboration on day one of the 2024 Christian Alliance for Orphans Summit in Nashville, TN, USA. We engaged the study with our multi-national, multi-cultural team to foster relationships and better understanding of our connections to each other and the work we all cherish. I, for one, was delighted by Dr. Siegel’s thoughts on this topic, and the conversations it started for us, and how enriched I was in participating in this first use of the material. I am eager to finish the entire study with our staff and board in a retreat setting. I hope your use of the material will initiate an equally inspirational discussion about the meaning of ONE TWENTY-SEVEN to enrich your spiritual life, enhance the understanding you have about these words of scripture, and deepen the relationship you have with your study partners. In the hands of the Almighty One, Dr. Melody Curtiss, esq. Helping Children Worldwide CEO

11 About the Cover Art “The Widow and the Orphan” is an original acrylic on canvas painting by a Sierra Leonean artist, who signed the work as “By Ali.” If you have been associated with Helping Children Worldwide in the past, you may recognize the artist’s style and be familiar with his work. Ali Turray painted the murals on the walls of the Child Reintegration Centre in Bo, Sierra Leone, and several original works of art commissioned for the Breaking Bread table fellowship series. His work depicts daily life in his deeply impoverished country, the rich beauty of its landscape, the depth of connection within family and community, and the hard-working nature and resilience of its people. In Sierra Leone, the average lifespan is 50 years, and 1 in 10 children are orphaned with the loss of one or both parents while they are still young. The plight of the widow and the orphan is always in view in Sub-Saharan Africa and beautifully captured here in the faces of the child and mother painted by Ali.

One Twenty-Seven 12

How to Use the Guide Setting aside 30 minutes for advance preparation before each group session will give you the best experience as you engage with this study of James. Take time to let the information and ideas sink in. It is possible to do all the discussion sessions in this study as a daylong program, but that gives you very little time to sit with each of the lessons, fully absorb the ideas, and reflect upon the deep spiritual context. Instead, we recommend that your study leader schedule four to five group study sessions (approximately 60 minutes each in duration), and a day or week between sessions to think. Let us offer you five easy steps for engaging: 1. Begin on your own individually by reading James Chapter 1:1-27. (Not too time consuming, it’s only a single page of verse!) Use more than one translation, if you can. Notice subtle differences among translations. Read your favorite version of James Chapter 1:1-27 again, so that the entire chapter is fresh in your mind. 2. Before you attend each group study session, fully read the associated short lesson in this study guide. For instance, if your group study session will focus on the "First Reading" in this study guide, read the study guide lesson titled "First Reading" before the group session. You can find the list of lessons in the study guide's Table of Contents.

3. As you read the lesson in the study guide, take notes about your own ideas, questions, and responses. These notes will help you to participate fully in the group study session and may also be helpful to others in your group. Don’t forget to check out the endnotes as you read each lesson, as you might find that they might aid in your comprehension. Reread James Chapter 1:1-27 on your own one more time, with the study guide's lesson fresh in your mind. Now you are ready to attend the group session! 4. When you attend the group session, listen to every other person’s perspective with curiosity and interest. Ask clarifying questions, but if you disagree strongly, write down your disagreement to share at the end of the session after you have reflected further on their perspective. 5. If you are unable to find time in your schedule to prepare for the study session, go to the session anyway, listen to the summary by the study leader and others, and feel free to join in the discussion if you have something to contribute.

FACILITATION TIPS FOR STUDY LEADERS EVERY SESSION: You can utilize the discussion questions at the end of each study lesson to help anchor your study group session. Pick at least one question and write 2-3 sentences as an answer. Assign somebody as timekeeper, so you can end discussion 10 minutes before the end of time for each chapter discussion. Have somebody read James 1:27 aloud to initiate each session. Remind them of the chapter title. Do not assume that every person had time to read the chapter or to prepare to discuss it. With that in mind, offer a summary of the content from your perspective, or ask somebody in advance to summarize the study lesson. Invite another person to contribute to the summary. Then use the questions at the end of each chapter to initiate and grow the conversation. Give the group an opportunity to share if anything during their time between sessions brought the study to mind. Conclude the discussion ten minutes before study time is concluded. Take five minutes to offer encouragement for the next week based on the discussion and ask for other positive take-aways. Provide reminders on next meetings or events. Conclude every chapter with a short prayer of encouragement regarding the lessons of the chapter. SESSION ONE: Do a time-limited icebreaker introduction of group members to one another, even if they are all acquainted with each other. This gets the group used to speaking freely in front of each other. FINAL SESSION: Play a song from the Strong Family Sunday playlist and ensure that your group has the links to the Strong Family for Every Child Website to find more tools for their next steps.

https://strongfamily4everychild.org/strong-family-sunday

A Note for Church and Faith Network Leaders You may use this study guide to follow up with the Breaking Bread Table Fellowship, or to introduce a larger faith initiative in your congregation or community. The study could be used across multiple churches or interfaith collaborations to support charitable ministries that provide faith dividends, with increased commitments and understandings about what it means to be fully engaged with spirit and humanity. We offer this study guide at cost, or free for download, however, it is a copyrighted work, so please do not make any revisions to the material in chapters One, Two, Three, or Four without express written permission of Helping Children Worldwide, Inc. You may use any of the ideas within its chapters as source materials as you craft homilies and sermons, and to enrich specific worship services. We ask, however, that you not revise the study without our express written approval, under our agreement with the author.

NOTES

NOTES 19

And So Begin. “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27).

One Twenty-Seven The Widow and the Orphan

Introduction to James 1:27

23 Introduction: What Are We to Do? You and I are created in the image of God. What in the world are we supposed to do about it? This is the question the author of James asks and answers in Chapter 1 of his letter. It’s a profound answer, a clear answer. And yet, we rarely meditate upon it or wonder how we might discover ourselves anew through it: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27). Parental Separation There are many ways that children become separated from their parents. There are many ways that women become widows and men become widowers. As I wrote these words, untold numbers of people were being orphaned and widowed from war and conflicts in Israel, Gaza, Ukraine, Russia, Sudan, Myanmar (Burma), and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). From the earthquake months ago and ongoing human rights abuses in Afghanistan, the landslide weeks ago in Papua New Guinea, and droughts and flooding in East Africa. In the USA, Customs and Border Patrol Officers have recorded over 500,000 encounters with unaccompanied children in the last four years, showing that the issue of family separation is an issue close to home. Many of these children end up laboring as a shadow workforce for products whose name brands might be familiar to you.1 Around the world today, approximately 140 million children are orphans2, of which 5-8+ million are estimated to be living in long-term institutional care3 (i.e. orphanages, hence separated from their extended families and home communities). As of 2022, over 8 million children globally are estimated to have become orphans due to COVID-19, with an estimated 75% of the deaths being that of a male caregiver in the household.4 A significant portion of orphans are living and working on the street (“street-connected”) and are at serious risk for abuse and trauma. It is unknown how many youths are street-

One Twenty-Seven 24 INTRODUCTION TO JAMES 1:27 connected as the data are hard to collect. A decades-old commonly cited figure is 100 million, with the number likely much higher.5 Over 1 million children have experienced the death of a parent due to drug overdose or gun violence during the last two decades in the USA,, with an estimated 40 children daily in the USA experiencing the death of a parent from gun-involved homicide (not including suicides).6 And according to the World Widows Report, there are about 258 million widows globally with 585 million children (including adult children). Of these, 38 million widow-headed families live in extreme poverty; many widows are victims of property seizures and fall into “survival sex” relationships as a means to provide for themselves and their children.7 Numbers like these are mind-numbing. However, if we value biblical commandments, we cannot allow ourselves to look away. In biblical parlance, how a society treats orphans and widows is the measure of a society’s morality, a kind of thermometer for a society’s health. Consider, for instance: Exod. 22:21. Every widow and orphan you shall not afflict.8 Deut. 10:17-18. For the Eternal your God is God supreme and Sovereign supreme, the great, the mighty, and the awesome God, who shows no favor and takes no bribe, but upholds the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and befriends the stranger, providing food and clothing. Deut. 24:19-21. When you reap the harvest in your field and overlook a sheaf in the field, do not turn back to get it; it shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow—in order that the Eternal your God may bless you in all your undertakings. When you beat down the fruit of your olive trees, do not go over them again; that shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow. When you gather the grapes of your vineyard, do not pick it over again; that shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow. Psalms 68:5-7. Sing to God, chant hymns to the divine name; extol the One who rides the clouds, the One whose name is Yah. Exult in God’s presence—the father of the fatherless, the judge [on behalf] of widows, God, dwelling in holiness. God restores the lonely to their homes. In biblical times, orphans and widows were especially vulnerable because they lacked immediate access to that sense of belonging, identity, and stability of

The Widow and the Orphan 25 status so necessary for the routine functioning of tribal society; this access was provided by the male family protector, by the father’s house. Indeed, the father’s house itself is such a key organizing idea that God invokes it the very first time God speaks directly to Abraham in Genesis 12:1, acknowledging the radical hardship of what God is asking Abraham to do: “God said to Abram, “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” (The word for “house” in Hebrew, bayyit, has many meanings including “home” and “family.”) To go forth from his father’s house would be a risky endeavor, seemingly leaving behind the protection, safety, and stability offered by a “father’s house” as such. How much courage it must have taken for Abraham to heed God’s call, knowing that he would be seen as a wandering stranger in the eyes of those whom he would encounter along his journey!9 Biblical widows and orphans, like tribal strangers, were at great risk of having their basic needs go unmet and were at great risk of being exploited. The 19th century scholar Samson Raphael Hirsch emphasized the vulnerability of widows and orphans through a linguistic interpretation of biblical Hebrew. He observed that the biblical Hebrew word for “widow,” almanah, likely derives from the Hebrew word-root a/l/m, meaning “to be silent”; he wrote that it is as if the biblical widow upon the loss of her husband metaphorically loses her voice, for with the husband’s death she no longer has a representative voice in society. She has no one to plead her cause. Furthermore, Samson Raphael Hirsh suggested that the Hebrew word for orphan, yatom, has a linguistic similarities with the Hebrew word-roots g/d/m and k/t/m, meaning “hand-mutilated” or “to cut the top off of (for instance, the top section of a tree),” respectively; he wrote that it is as if the biblical orphan upon the loss of the father metaphorically loses a hand, for with the father’s death the orphan no longer has a leading hand upon which to rely10. Samson Raphael Hirsch used these Hebrew linguistic interpretations to highlight the unique hardships faced by biblical orphans and widows, who experienced acute losses emotionally, financially, socially, and legally. In the Bible, orphans-and-widows are a kind of categorical unit (and thus I will often hyphenate them together in this study). Indeed, they are almost always grouped together in the biblical imagination. Contemporary theology scholar JT Fitzgerald of the University of Notre Dame explains, “The English word "orphan" today is used almost exclusively of a child who has lost both parents due to death. In antiquity, by contrast, children who had lost either the father or the mother were routinely regarded as orphans. Given the patriarchal world of antiquity, it is not surprising that the focus was on the loss of the

One Twenty-Seven 26 INTRODUCTION TO JAMES 1:27 father, so that the orphan was typically regarded as "fatherless." This is seen above all in the frequent association of orphans with widows, with the latter having lost her husband and the former their father.”11 Biblical law thus requires that we attend to the needs of orphans-and-widows with special sensitivity and care, assisting them to feel at home rather than homeless--for home in the ancient Hebraic imagination is house, family, community, tribe, place of belonging, and foundation for access to justice. Hence the beautiful, commanding vision of Psalm 68:5-7: “Sing to God, chant hymns to the divine name; extol the One who rides the clouds, the One whose name is Yah. Exult in God’s presence—the father of the fatherless, the judge [on behalf] of widows, God, dwelling in holiness. God returns the lonely to their homes”—homes, in the broadest sense of that word. And so shall we do all that we can in our own time to sing forth this song of Psalm 68, to partner with God in returning the lonely to their homes. Psalm 68 concludes, “You are awesome, O God, in Your holy places / it is the God of Israel who gives strength and power to the people. / Blessed is God.” We, who acknowledge the One who gives us strength and power, have an obligation to use our strength and power to lift up those who are most vulnerable. We know that when children in our world today are forcibly separated from their homes, their families, and their communities due to violence, poverty, plague, child trafficking, or caregiver incapacitation/death, it is more than simply not okay. Just like in biblical times, it is the clearest indicator that our society is unwell and it requires us to take action. With this timeless teaching in mind, we turn to Chapter 1 of James. Throughout the Bible, orphans-and-widows are frequently mentioned alongside the poor, the oppressed, and the foreigner. James locates the essence of our tradition in God’s commandment to care for those who are singularly at risk of exploitation and neglect in our society: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans-and-widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27). As we have noted, the statistics of our modern era can be numbing, with so many children separated from their families and so many caregivers needing support. It might help each of us to rouse ourselves for this cause if we frame our efforts as a spiritual practice. Indeed, it is this spiritual practice that Chapter 1 of James urges us to take up, to commit to as a lifelong endeavor. Let’s read through Chapter 1 multiple times, receptively, and dare to see where it leads us.

27 WHO WAS JAMES? WHO WAS JAMES? A note about names and such, before we dig in. I refer to the author of James as “James.” There’s a strong Christian tradition of crediting the letter to James, brother of Jesus. If that’s true, then the letter was written sometime before the year 62CE, the year of James’ execution. Did James, brother of Jesus, actually pen the text? Its exquisitely refined Greek language would likely have been a linguistic stretch for the likes of a Galilean from humble background! Perhaps the letter was written by a highly educated person trained in Greek prose who recorded messages from James, brother of Jesus, and transmitted the messages in fine language. Or perhaps James was written by someone else who believed himself to be teaching in the tradition of James, brother of Jesus, as some of the early Church Fathers thought. I also refer to the author of James as “James” even though technically speaking, it’s more accurate to call him “Jacob.” The letter in the original Greek begins, “Iakobos, a slave of God and of the Lord Jesus Christ.” This Iakobos is likely a Jewish follower of Jesus. Iakobos is the Greek rendering of the Hebrew name Yaakov, since many Jews at the time Hellenized their names (for instance, the Apostle Paul’s Hebrew name was Sha'ul, which in English is “Saul.”) Yaakov is a common Hebrew name, usually translated into English as “Jacob.” So how did this Iakobos/Yaakov/Jacob come to be called “James” instead of “Jacob”? The shift occurred over time: Yaakov Hellenized his Hebrew name into Greek (“Iakobos”), which then in many Latin biblical translations from the Greek became “Jacomos,” which then in Old French / Spanish / Italian biblical translations became “Jammes,” “Jaime,” and “Giacomo,” respectively, and in English biblical translations became “James”!12 So, there you have it. Instead of calling Jesus’ brother “Jacob,” and instead of calling the writer of this letter “Jacob”—as would make the most sense from the Hebraic origins of the name Yaakov--I’ll stick within the English tradition and use “James.”

One Twenty-Seven 28 But why does it matter, these linguistic acrobatics in a name? It matters because we do ourselves a disservice if we overlook the Jewish background of James. In fact, James has come to be recognized as one of the most “Jewish” of the New Testament writings. As theologian A.K.M. Adam of Oxford University writes in his book James: A Handbook on the Greek Text, “The letter richly illustrates an environment in which faith in Jesus did not entail a radical separation from the movement’s origin in Judaism.”13 The author of James is intimately familiar with the Jewish scriptures and the Jewish people. For instance, James opens his text with a greeting in 1:1, “To the twelve tribes in the Dispersion” -- the Dispersion being a Jewish way of referring to the Jews across the diaspora outside of Jerusalem, wherever they might live. It was not an uncommon greeting for Jews to address fellow Jews in this manner; we have a record of the ancient Jewish teacher Rabban Gamaliel addressing a letter similarly, as recorded in the Jewish Talmud: “To our brothers, the people of the Dispersion in Babylonia, and to our brothers who are in Medea, and to the rest of the entire Dispersion of Israel, may your peace increase forever.”14 As for the author of James, we do not know whether he intended his letter specifically for fellow Jewish followers of Jesus, or rather invoked the Dispersion metaphorically to include any followers of Jesus who, like the Jews, were spread out wherever they might live. Martin Luther in the 16th century famously relegated James to an appendix of his Bible, concluding to his University of Wittenberg students: “We should throw the epistle of James out of this school, for it does not amount to much. It contains not a syllable about Christ. Not once does it mention Christ, except at the beginning (James 1:1, 2:1). I maintain that some Jew wrote it who probably heard about Christian people but never encountered any. …Besides, there’s no order or method in the epistle.”15 I beg to differ with Martin Luther’s critique! Theologians and researchers have long noted that the text of James shares themes and imagery with Jesus’ ‘Sermon on the Mount’ and ‘Sermon on the Plain.’ Moreover, the Jewish author of James was likely familiar with ancient rabbinic forms of analysis which hold lightly to topical threads while touching upon subtopics, images, or questions that may arise—similarly to the way we might open a Wikipedia page and click on a linked word in one of the paragraphs, which then opens a new Wikipedia page, and we click on yet another linked word on that new page, and on and on, and back and forth, returning to the original page we started with and clicking on additional linked words, etc.—all the while holding

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 29 in our minds an awareness that the pages form a network of associated ideas. Nowadays, as the Church is increasingly appreciative of the New Testament’s Jewish roots, we add depth to our understanding of James by reading it together with ancient Jewish ideas and precedents. As we read through James Chapter 1, may we listen for that still small voice that indeed builds toward a clear, distinct message: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27).

Notes 30 WHO WAS JAMES?

Notes 31 WHO WAS JAMES?

First Reading

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 33 Collective Responsibilities On the Spiritual Practice of Sharing Sacred Collective Responsibilities Martin Buber, theologian and philosopher, recounted a famous Jewish legend in his book Tales of the Hasidim. The legend is about a rabbi who was born in the 18th century, in what is now southern Poland. The rabbi was named Zusya, and he was beloved far and wide for his humor, piety, and ability to see the Divine light within everyone he met. This is the legend: shortly before his death, Zusya said: “In the world to come [after my death], I shall not be asked: ‘Why were you not Moses?’ I shall be asked: ‘Why were you not Zusya?’”16 The legend of Zusya teaches that God wants us each of us to live uniquely. When Zusya stands before the heavenly host after his death and is called upon to make an account of his life, there is no shame in Zusya not being a Moses, or a Mother Teresa, or a Gandhi. Quite the contrary. Like a motivational speaker, God is saying, “Thou Shalt Be Yourself!” Do your own thing, find your own way, and be excellent at it. Yet, as much as the Zusya story seems especially fitting for our modern Western world with its emphasis on the individual, if we think the story is only about individual purpose we miss the point. The Jewish context of the Zusya story assumes a basic recognition on the part of the storytellers and listeners that it is the collective, not the individual, that is the beating heart of our sacred covenant with God. It is within a shared set of sacred responsibilities—responsibilities to be upheld by the collective as a whole--that Zusya will be asked upon his death how he lived out those responsibilities uniquely as an individual. When the Jewish people stood at Mount Sinai and accepted the Torah, we did so collectively, as a people. Not as an individual. (“All that God has said we will do,” Exodus 19:8; “We will do and we will hear,” Exodus 24:7). Hence every Jewish teacher in the New Testament—including James--would likely have understood that God’s primary covenantal relationship is with the collective, not the individual. Thus, if you want to live a purpose-driven life, you don’t ask: what is God’s will for me? You ask: what is God’s will for us, as human beings mutually responsible for one another? The Apostle Paul, from his Jewish worldview, illustrates this point beautifully in 1 Corinthians 12:

One Twenty-Seven 34 FIRST READING “For in one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit…There are many members, yet one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor again the head to the feet, “I have no need of you.”…The members of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable… God has so arranged the body…[so] the members may have the same care for one another. If one member [of the body] suffers, all suffer together with it; if one member is honored, all rejoice together with it. “ Our fates are intertwined, and thus the constituent members of the body share an essential feeling of “being with” one another. It’s the feeling of having concern for all the other parts of the whole, because if one part of the body is not well, the other parts feel it. And if one part of the body feels good, it lifts up the rest. In Judaism, this value of being interconnected and responsible for one another has come to be known in Hebrew as arevut. An arev in Hebrew is a guarantor, like a guarantor on a loan. Arevut means that we are all guarantors for one another, we are all responsible for one another. The ancient Jewish sages of the Holy Land also taught about this value, in the post-biblical collection of oral teachings, Vayikra Rabbah: Ḥizkiya taught: “Israel are scattered sheep” (Jeremiah 50:17). Israel is likened to sheep. Just as, if a sheep is struck on its head or one of its limbs all its limbs feel it, so it is with Israel; one of them sins and all of them feel it. “Shall one person sin, [and You will rage against the entire congregation?]” (Numbers 16:22). Rabbi Shimon bar Yoḥai taught: This is analogous to people who were sitting in a ship. One of them took a drill and began drilling a hole. His counterparts said to him: ‘What are you sitting and doing?’ He said to them: ‘Why do you care? Am I not drilling under myself?’ They said to him: ‘Because the water will rise and flood the ship we are on!’17 We are all in one boat, our welfare and our fates intertwined. No matter where Israel scatters—whether it be to foreign pastures of Assyria or Babylon (as in the Jeremiah reference, above), or elsewhere, if one is in trouble, all are in trouble. If one tries to sink the collective ship, all are at risk. And so we must be responsible for one another’s wellbeing, we must take action. Hence whenever any Jewish writer in the New Testament addresses a broad collective, as James does in the opening of his letter, our ears would do well to be attuned to this underlying value of arevut.

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 35 James writes in 1:1-2, “To the twelve tribes in the Dispersion…My brothers and sisters…”. With this opening, James is not blasting out to the world the equivalent of an ancient email to a group listserv, in which each person is to read the message individually on his or her own laptop, seeking to discern an individual purpose in it. No. The collective address of James’ teaching is meant to be heard by the scattered sheep, the scattered sheep assembled in groups. Most individuals at the time would have been illiterate, so these would be groups that strengthen their sense of collectivity by the very act of hearing the teaching together, pondering it together, discussing it together, and experiencing themselves as a body together, knowing that there are also other groups in the Dispersion that, too, will be hearing and pondering and discussing and experiencing James’ instruction: one collective, one body, united across geographical space and time. And this one collective whom James addresses, bound together in a sacred covenant with God, has a set of shared sacred covenantal responsibilities inscribed upon their hearts, a set of responsibilities to uphold with collective purposefulness aimed at a collective purpose. What, according to James, epitomizes this set of shared sacred covenantal responsibilities? “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27). How you, as an individual, carry out the collective responsibility of visiting orphans and widows, and in this spirit keep yourself unstained from the world—is a matter of your own style. Just as Zusya had his style, and Moses had his. The stakes of collective responsibility couldn’t be greater. James’ emphasis on orphans and widows is reminiscent of the famous biblical ceremony that occurred right after the Israelites entered the Holy Land, between Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal, as recorded in Deuteronomy. The Levites call out eleven primary curses to which the entire nation as one answers “Amen,” affirming their covenantal commitment. Among these curses is: “Cursed be the one who subverts the rights of the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow.—And all the people shall say, Amen” (Deuteronomy 27:19). The biblical text is very graphic here! Extraordinary blessings shall come to our collective if we uphold the covenant with its justice for the most vulnerable in our midst, whereas horrific curses shall come to our collective if we shun our covenantal mutual responsibilities: crops will fail, wars will come, and socioeconomic conditions will deteriorate so starkly that starving parents will eat their children’s corpses (Deuteronomy 28:53).

One Twenty-Seven 36 FIRST READING This image of societal deterioration is not the vicious, capricious threat of a violent deity but rather a warning of intense concern expressed by the pained, righteous anger of a loving God. In Exodus 22: 21-23, we hear God’s pain on this topic; note God’s doubled words, which stylistically are an ancient Hebrew poetic technique to indicate emotional intensification: (21) Widow and orphan you are not to afflict. (22) Oh, if you afflict-afflict them…! For [then] they will cry-cry out to me, And I will hearken-hearken to their cry, My anger will flare up And I will kill you with the sword, So that your wives become widows, and your children, orphans!18 God is saying to us listeners: it is vital to Me that you truly internalize My abhorrence of the very idea that you would dehumanize widows and orphans. God evokes this abhorrence, poetically causing us to feel the intensity of these gut-wrenching words; we experience abhorrence as we imagine that God would kill us with the sword, widow our partners, orphan our children. No, that cannot be, what horror, we think. Rhetorical mission accomplished: God really, really, really wants us to pay attention to the plight of widows and orphans, and to do right by them!19 Ibn Ezra, a rabbi and poet who lived in Spain in the 11th-12th centuries, wrote about how this passage in Exodus 22 calls us to our collective covenantal responsibilities. He noticed a grammar shift that happens from Exodus 22:21, to 22:22, and again to 22:23, and found significance in it. I’ll try to highlight this shift by retranslating the verses even more literally: o Verse 21 in the original Hebrew addresses the plural group, using a plural verb: “Widow and orphan you collectively are not to afflict!” (you, plural) o Verse 22 strangely uses the singular: “Oh, if you (singular, individually) afflict.” o Verse 23 returns to the plural: “I will kill you collectively, so that your wives become widows and your children, orphans.” (you, plural) In full, it reads like this: (21) Widow and orphan you collectively are not to afflict. (22) Oh, if you [singular] afflict-afflict them…! For [then] they will cry-cry out to me, And I will hearken-hearken to their cry,

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 37 My anger will flare up And I will kill you collectively with the sword, So that your wives become widows, and your children, orphans!20 Here’s how Ibn Ezra interprets the seeming discrepancy of the shift from the plural to the singular, and back to the plural again across verses 21, 22, and 23: “Do not afflict (verse 21), in the language of collective plural: because the law regarding those who see the affliction and remain silent is the same as the law regarding the one who does the actual afflicting, thus the text reads if you afflict (singular, verse 22) and I will kill you (plural, verse 23).”21 In other words, as Ibn Ezra writes in another commentary22 on this verse, “Whoever sees a person afflicting the orphan and the widow and does not aid them, is also considered an afflicter.” The law is one and the same for a perpetrator and a bystander. We are all responsible for one another’s actions. Or as we know from modern expressions: no person is an island, we rise and fall together. Does this idea of collective covenantal responsibility (arevut) strike you as too heavy a burden to bear? Or perhaps as an assault on individual freedom? Might it lead to a tyrannical society in which we spy on each other, hypervigilant for the slightest hint of transgression? And nowadays with technology, if we can “see” affliction and know that it is happening right now across our cities, our country, our world, are we, too, “afflicters” if we do not act? To the modern mind, all of these questions are certainly questions worth pondering. On the flip side, however, well-intentioned and well-executed arevut may be more necessary in our contemporary era than ever before, given that excessive individualism is taking a toll on mental health and loneliness is already a public health conundrum. Moreover, according to Jewish traditional teachings about arevut, there is dignity in participating in mutual obligation to one another. Even the poor are to view themselves as guarantors, obligated to carry out shared sacred covenantal responsibilities. As the ancient Jewish teacher Mar Zutra taught, “Even a poor person who subsists on charity should give charity.” Similarly in Luke 21:2-3, Jesus lauds the widow who, even in her poverty, puts two small copper coins into the community’s collection-box/treasury. This recognition of the essential dignity of participating in shared sacred covenantal responsibilities is arguably why Jesus in Luke 21:5 follows up his teaching about this widow with a teaching about the Temple in Jerusalem: even when the Temple will be destroyed, even when the Temple’s former adornment of

One Twenty-Seven 38 FIRST READING beautiful stones becomes merely a memory, even when the Temple seems to be impoverished in its widowed desolation, Jesus’ followers must not forget her essential dignity. Those who understand Jesus’ teaching, who in their wisdom can endure the destruction of the Temple, and, as the body of Christ, will constitute that widowed Temple—such early and persecuted followers of Jesus in their apparent poverty and powerlessness, too, shall trust that they have not forfeited their dignity. Their steadfast dedication to the unbroken covenant shall live on, Jesus teaches, in their mutual, reciprocal care for one another, in community. May it be so, today. Discussion Questions ● Have you ever felt that others’ sufferings and joys in some essential way, perhaps even surprising way, are also yours? That others’ fates and responsibilities are yours? Think of one concrete example from your own life. ● Pause to envision how Jesus in his own way, and Moses in his own way, and Zusya in his own way, and even that widow of Luke 21:2-3 in her own way, might have cared for widows and orphans. What individual qualities might each of them bring to this shared sacred covenantal responsibility? ● Consider how you individually have assisted and/or afflicted widows-and-orphans locally, nationally, or globally. Consider, as well, how your study group as "one body" has assisted and/or afflicted widows-and-orphans. ● What do you find spiritually challenging and exciting about the idea that you are mutually responsible for one another's actions, as "one body" (1 Corinthians 12), sitting on one ship (Vayikra Rabbah)?

NOTES 39

Second Reading

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 41 SECOND READING Our Genesis-Selves On the Spiritual Practice of Recognizing Our Genesis-Selves James teaches us in 1:16-18 that we have been created intentionally by God: “Every generous act of giving, with every perfect gift, is from above, coming down from the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change. Of God’s own will, God brought us forth by the word of truth, so that we would become a kind of first fruits of God’s creatures.”23 In the original Greek, “brought us forth” is from apokyeo, to give birth, to swell with life from the womb (from the Greek root kuo, to swell, curve, bend). It is quite a mysterious and poetic image of an intended pregnancy.24 Continuing with the theme of fertility, James urges his listeners in 1:21 to welcome collectively and with gentleness the “implanted word,” the implanted logos, which God has purposefully sown in us for good. “Implanted” in the Greek comes from a root verb phyo that means “to produce,” “to grow forth,” the same root verb that the author of Luke 8 uses when he shares Jesus’ Parable of the Sower: whereas some seed falls on rocky soil and withers as soon as it begins to grow forth from the ground, other seed falls on good soil and grows forth to produce a hundred fold. Like good soil, our role is to nurture this implanted word to its full term, to birth and produce goodness in the world. This is such an optimistic vision! I must admit that as someone not raised in the Christian tradition, I often find myself feeling frustration and sadness that so many Christians are taught to be almost singularly consumed by--and constantly anxious about--a felt sense of their own essential sinfulness. While no tradition speaks with just one voice, it seems to me that so much of the New Testament, as indeed much of Jewish tradition, emphasizes quite the opposite! You are created by God's elevated goodness, James teaches. God birthed you into this world specifically and intentionally to be fit for a divinely good purpose! God’s word of truth is implanted in you! In ancient days, the vocabulary was predominantly agricultural and environmental—you’ve been implanted to be good, to do good. Had the New Testament been written today, maybe James would have used tech terms: you’ve been programmed to be good and to do good. How can you not go

One Twenty-Seven 42 SECOND READING about your day just beaming about this, like your whole self can’t help but smile?!? In the Christian scriptures, the followers of the way of Christ are clothed in Christ, have the mind of Christ, comprise the body of Christ, have hearts engraved with a letter of Christ, and are born as goodly first fruits; how much wisdom you all have been given, to align with the persons you were created to be! As we are created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27), we are born to follow God’s sacred attributes. In Leviticus 19:1-2 we learn, “The Lord spoke to Moses and said, ‘Speak to the entire community of the Children of Israel, and say to them: Holy are you to be, for holy am I, the Lord your God.” There is an ancient Jewish teaching about what it means to follow God’s sacred attributes: “Rabbi Ḥama, son of Rabbi Ḥanina, says: What is the meaning of that which is written: “After the Lord your God shall you collectively25 walk, and God shall you collectively fear, and God’s commandments shall you collectively keep, and unto God’s voice shall you collectively hearken, and God shall you collectively serve, and unto God shall you collectively cleave” (Deuteronomy 13:5)? But is it actually possible for a person to follow the Divine Presence? But hasn’t it already been stated: “For the Lord your God is a devouring fire, a jealous God” (Deuteronomy 4:24), and one cannot approach fire.“ He explains: Rather, the meaning is that one should follow the attributes of the Holy One, Blessed be God. He provides several examples. Just as God clothes the naked, as it is written: “And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife garments of skin, and clothed them” (Genesis 3:21), so too, should you clothe the naked. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be God, visits the sick, as it is written with regard to God’s appearing to Abraham following his circumcision: “And the Lord appeared unto him by the terebinths of Mamre” (Genesis 18:1), so too, should you visit the sick. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be God, consoles mourners, as it is written: “And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son” (Genesis 25:11), so too, should you console mourners. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be God, buried the dead, as it is written: “And he was buried in the valley in the land of Moab” (Deuteronomy 34:6), so too, should you bury the dead.26

The Widow and the Orphan 43 When we carry out our shared sacred covenantal responsibilities such as clothing the naked, visiting the sick, consoling mourners, and burying the dead, we not only uphold our side of the covenant with God, we live into ourselves-as-we-are-created-to-be: the image of God. We do as God does. It is this perspective we can bring to our reading of James 1:27. “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.” In other words, show up for orphans and widows, plead their cause, restore the lonely to their homes, like God does. Follow God’s sacred attributes.” I’ve often heard James described as a text that is principally about the Christian faith-versus-works debate. Maybe so. Yet, to me such a single focus misses what is, from a Jewish context, the broader and deeper question of how we are to manifest being created in the image of God. In James’ view, if you do not carry out such shared sacred covenantal responsibilities as caring for orphans and widows, you will forget whom it is that God has birthed you to be. You will be, as James writes in 1:22-24, “like a person who observes their natural face in a mirror: for you observe yourself and go away and at once forget what you were like.27” The word commonly translated as “natural” here is from the Greek root word genesis. In James’ beautiful language, he is saying that if you don’t do what you were created to do, it is as if you only momentarily behold in a mirror - the Genesis-You, the you-of-your-birth, the you-of-your-sacred-lineage, the you-born-from-God’s-own-will-and-from the stuff-of-God’s-own-word-of-truth-itself, and oh!— --that fleeting image of you as reflected in a mirror then slips away from your mind, because you lose it from your awareness when you don’t use it, when you don’t act upon it, you don’t cultivate it in a deeper, more profound way. It’s no wonder so many of us lose our ability to trust in ourselves and so many of us struggle with a sense of purposelessness. When I was training in chaplaincy at University of Michigan hospital, my teacher constantly reminded our training group about David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle: human beings learn best when we experience something, reflect upon it, conceptualize it, and then experiment again through action. And on and on. That’s how we grow and refine. You can’t just hear about something, theorize about it—you’ve got to do it, for better or for

One Twenty-Seven 44 SECOND READING worse, reflect on what happened, draw lessons and understanding from it, and get back to doing it again. Every time I’d go into a patient’s hospital room, I’d never know what I would be facing and it would often be tough. I remember every one of those visits. A young man being discharged into hospice, his fiancée at bedside; a dying toddler; a church leader who couldn’t speak because his larynx had been surgically removed, a Muslim woman’s brain dead child, a cancer patient hoping for a miracle. I am the chaplain and psychotherapist that I am today because of them, and because of how I came into “being myself” as I cared for them, refining my skills and learning to trust God to work through me. No study, theory, or listening to instruction on its own could possibly have accomplished this. The ancient rabbis in the Holy Land famously had a debate: what’s more important, study of sacred teachings or putting those sacred teachings into action?28 Rabbi Tarfon said that action is greater, and Rabbi Akiva said that study is greater, because it leads to action. The elders who were present then affirmed: yes, study is greater, because it leads to action! The two are intimately connected, study and action. It seems to me that this study-and-action combination is what James is getting at, then, when he urges his listeners not to look fleetingly into a mirror but rather, “look intently into the perfect law/Torah, the law/Torah of liberty, and stick with it, being not hearers who forget but doers who act” (James 1:25). Look intently into the entire wellspring of our traditional heritage to understand our sacred covenantal responsibilities and keep at it, over the course of our lifetimes, as a collective throughout our generations. James uses a somewhat unusual word in 1:25 for “look intently”: from parakypto (that is, para--with, and kypto—stooping, bowing the head), metaphorically here in the sense of “looking with head bowed forward; looking into, with the body bent; stooping and looking into.” For me, this calls to mind the posture I tend to assume when I sit and look intently into sacred texts, as I mull over every word--as I am doing now as I write this! For the ancient followers of Jesus listening to James’ teaching here, this unusual word parakypto might have called to mind phrases recorded in Luke 24:12, John 20:5, and John 20:11—that is, when those who stooped to look intently (parakypto) into Jesus’ tomb found that it was empty. It may be that for James in 1:25, this specific kind of looking intently (parakypto) into the law of liberty means the law of liberty as indicated by that empty tomb, the law of liberty of the resurrected Christ.29 When you look intently into the law of liberty again and again, you experience again and again your having been birthed by God into freedom. You behold your Genesis-You. The heritage of sacred teachings is a metaphorical mirror,

The Widow and the Orphan 45 an enduring mirror that has recorded and reflects back at us our deepest selves-as-refined-through-action, encompassing our entire community as one, over generations. When you look intently into this heritage, may you feel in your bodies and perceive in your minds God’s implanted word that is already within you! For with this implanted word, you were brought forth by God as natural doers of that very word, fulfillers of that law of liberty: living into your freedom by upholding sacred covenantal responsibilities. What, for James, is the essence of those sacred covenantal responsibilities? Here we come to that crescendo of James 1:27: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.” How exactly is James 1:27 an invitation to understand more deeply your Genesis-You? The key clue is in the original Greek phrase in James 1:27, “to visit orphans and widows in their affliction,” which arguably invokes the exodus story from the Hebrew Bible. God visited the Israelite slaves in their affliction and redeemed them from Egypt: James 1:27 Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to visit widows and orphans in their affliction… Exodus 4:31 And the people believed/trusted: And when they heard that the Lord had visited the Children of Israel, had looked upon their affliction…

One Twenty-Seven 46 SECOND READING Notice the same Greek words used in James 1:27 and in the Greek of Exodus 4:31 (the Septuagint, i.e. the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible that James likely would have known): James 1:27 (English) James 1:27 (Greek transliteration) Exodus 4:31 (English) Exodus 4:31 (Greek transliteration Septuagint) Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: And the people believed/trusted: And when they heard that the Lord to visit episkeptesthai (from the word episkeptomai) had visited epeskepsato (from the word episkeptomai) widows and orphans the Children of Israel, had looked in their upon their affliction… thlipsei (from the word thlipsis) affliction… thlipsin (from the word thlipsis) then they bowed their head30 and worshipped. In the Jewish worldview, our entire worship and agricultural calendar revolves around the exodus redemption story. Every year, we reenact that redemption with our holidays, marking it not only as history but also as a constantly unfolding event that we, too, participate in as if we were those very slaves in Egypt, our ancestors.31 James would likely have assumed that his listeners, too, are inheritors of the exodus legacy, and as such they could view themselves as participants in the exodus story: when those enslaved Children of Israel bowed their heads upon being visited by God, that experience lives on in me and it lives on in you. Episkeptomai, the root word often translated as “visit” in James 1:27 and in the Greek Septuagint of Exodus 4:31, actually has wider-ranging meanings that include “look at, look for, go see how someone is doing, look upon in order to

The Widow and the Orphan 47 provide for.” (The Greek syllable “skep” has the same root as the English “scope,” like a microscope or telescope enables us to see.) The Greek episkeptomai thus suggests a willingness to approach with genuine care, to see-in-order-to-do. This is what God does for the enslaved Israelites in Exodus 4:31: “And the people believed/trusted: And when they heard that the Lord had visited (episkeptomai) the Children of Israel, had looked upon their affliction,32 then they bowed their heads and worshipped.” Why did the enslaved Israelites worship, right then and there? Because they knew that in God’s seeing them, God would take action to deliver them from their bondage. The enslaved Israelites weren’t just being seen, they were being seen by the One-who-wanted-and-could-and-would-deliver-them. When God shows up for you, you know you’re in good hands and something’s going to get done. We began this discussion of Chapter 1 with James’ characterization of God as the One who births first fruits into being: “Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights…Of God’s own will, God brought us forth [from apokyeo, to give birth] by the word of truth, that we should be a kind of first fruits of God’s creatures” (James 1:17-18). We follow God’s attributes when we in turn bring forth the implanted word, producing goodness from within ourselves into the world--like fruit trees that in turn yield more such seed-bearing fruit (Gen. 1:11), like fig trees that produce more figs (James 3:12). As James teaches in 3:17-18: “The wisdom from above is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, open to reason, full of mercy and good fruits, without uncertainty or insincerity. And the harvest of that-which-is-right-and-just is sown in peace by those who ‘do’ peace.” God freed the Israelite slaves, and likewise God has birthed you into freedom. Now it’s up to you, James teaches, to do as God does: redeem those who are enslaved in your contemporary world. The orphans-and-widows of James’ era, and indeed in our era today, are reminiscent of the enslaved Israelites—vulnerable, resilient, in need of allies to be with them in the quest for justice and freedom. Champion their cause, restore them to their homes. When you follow God’s attributes, becoming doers of God’s implanted word, you not only discover your birthright, your Genesis-You, your Genesis-Us; you also participate in the collective responsibility of birthing a uniquely divine redemption of the world. Together, across generations. And together with God.

Dr. Andrea Siegel, Helping Children Worldwide Curriculum Development Team 48 SECOND READING Discussion Questions ● What is easy or hard for you about truly seeing others as created in the image of God? What is easy or hard for you about truly seeing yourself as created in the image of God? ● Take a moment to reflect upon an example from your life when you took action to assist others in a way that was God-filled. It can be a big or small example. o As you meditate upon this, try to deepen your awareness that through this action, you come closer to your Genesis-You. What do you notice? o As you continue to meditate upon this, try to deepen your awareness that through this action, you come closer to the collective Genesis-Us. What do you notice? ● What attributes or qualities of God could you see yourself bringing into your sacred responsibility to care for orphans-and-widows? o To answer this question, you might discern such attributes or qualities of God based upon your lived experiences; and/or, you might peruse some biblical texts that specifically mention how God cares for orphans-and-widows, such as: Deut. 10:18, Jer. 49:11, Psalm 68:4-7, Psalm 10:17-18, Psalm 82:3-4, Psalm 146:7-9.33

NOTES 49 SECOND READING

Third Reading

51 THIRD READING Worshipping by Doing On the Spiritual Practice of Worshipping-by-Doing, Over and Over Again We’ve learned from James that we’re obligated to care for orphans-and-widows. And we’ve learned that we’ve been created fittingly for this sacred collective responsibility. But how do we even begin to take action? Isn’t the need just too overwhelming? Won’t we get lost amidst the challenges? How are we to find the wisdom to persevere? I’m a chaplain and a psychotherapist. One of my therapy clients, a young woman in her twenties, came into my office some weeks ago and shared that she has been feeling overwhelmed by a sense of inescapable negativity all around her. She reported feeling as if, metaphorically, she has been gasping for air, unable to find oxygen amidst the constant barrage of doom—politics, the economy, wars—that has taken over social media, the news, even conversations with friends. To escape it, she has been spending hours every day at home playing video games and watching movies. She tells me that she much prefers the fantasy worlds to reality, and she finds comfort that she can navigate those worlds with a game controller in her hands. Reality is too confusing. Full disclosure: listening to my client, I thought to myself, I could be her. I struggle to cut through the distractions and bewilderments and bad news and challenges of our contemporary world. Our brains cannot process so many stimuli all at once, with so much information coming at us from advertising, news (mostly of disasters, political scandals, fringe controversies to divide us, no?), the busy-ness of email and texting and various apps, the artificial flavors and colors in our foods. Add to that the financial systems we can no longer understand (cryptocurrency, hedge funds, interest rates, multinational corporations, the tax code). And advancements in artificial intelligence that make it almost impossible to tell what’s real (deepfakes, algorithms determining what news we see, computers generating code that even experts can’t explain). Is it not a miracle that we are staying even somewhat sane…? Hence when James offers counsel in Chapter 1, saying, “If any of you is lacking in wisdom…” (1:5), my ears perk up. “If any of you is lacking wisdom, ask God,

One Twenty-Seven 52 THIRD READING who gives to all generously and ungrudgingly, and it will be given you” (1:5). Another disclosure: I’m not great at asking God for wisdom. It’s so much easier to ask strangers on Facebook or Reddit or to start a conversation with ChatGPT. The truth is, though, that while digital platforms and tools might offer some useful crowdsourced opinions, little-known facts, or massive data calculations, on their own they’re not great sources for wisdom. Wisdom is deeper, grander, older, enduring-er, rooted-er, awe-filled-er, taking-in-a-slow-breath-intentionally-er, comes-by-understanding-and-embodying-a-life-well-lived-er. Is there any doubt that there is wisdom, for instance, in the following words spoken by the biblical prophet Isaiah (1:17)? Learn to do good. Devote yourselves to justice; Aid the wronged. Uphold the rights of the orphan; Defend the cause of the widow. Such unchanging fundamental sacred responsibilities are our collective anchor and lifeline. This is the ethos at the heart Rabbi Akiva’s teaching we read about in our last discussion, that study leads to action. Learning stirs within us the convictions and clarity of purpose to manifest such prophetic wisdom. In James 1:27, we find the spirit that famously animated the prophet Isaiah: “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to look-upon-and-care-for orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.” The word “religion” here (in Greek, thrēskeia) isn’t a philosophy or a worldview, it’s not a set of doctrines you simply hear and assent to. Thrēskeia is the set of ceremonial worship rites that people do repeatedly throughout their lives as an honor due to the divine. We have archeological evidence of inscriptions from ancient Greek pagan cultures in which thrēskeia refers to the rites offered in service to the Greek god Apollo or to peoples’ ancestral gods.34 In Jewish ritual observance, examples of thrēskeia could be daily (for instance, saying daily prayer), weekly (observing the Sabbath), monthly (purification rites, new moon observance), seasonally (agricultural rites), annually (sacred festivals such as the Passover seder), seven-year cycles (letting the land rest, forgiving debts), and more. Hence when James urges us to labor on behalf of orphans and widows, he doesn’t mean “to look-upon-and-care-for orphans-and-widows in their affliction” just once, or just as an optional charitable deed. It’s not a one-time item to check off our to-do lists, it's a doing we are to do repeatedly throughout our lives and over generations, as a collective obligation that is an expression of our fealty to the Divine whom we worship.

The Widow and the Orphan 53 Thus, James is saying here that when you look into the law of liberty and keep at it (1:25), the form of ceremonial worship that such learning of the law will stir your Genesis-You and our Genesis-Us to manifest is not what the casual observer might expect. It’s not animal sacrifices at the Temple (though certainly there’s something to that), it’s not even prayer alone (though certainly that’s important), and it’s not even hearing the word of God (though that’s certainly vital, too). It’s learning-to-do, it’s persevering to look-upon-and-care-for orphans and widows in their affliction, again and again. That’s Worship with a capital W. That’s pure and undefiled thrēskeia as seen by God, in the presence of God, as a way of serving God, as an obligation due to God, as we come ever closer to God. Would you agree with me that it is stunningly beautiful, what James is teaching here?!? This reminds me of an ancient Jewish legend from rabbinic literature. The rabbis are discussing Numbers 28:1-2, which details the worship of God through the Temple sacrifices. Commenting upon this in light of the many biblical commands to care for those who are vulnerable, the rabbis envision God as saying to Israel, “My children, whenever you give sustenance to the poor, I attribute it to you as though you gave sustenance to Me.”35 Let’s pause here to review Jesus’ teachings in Matthew 18:1-5, Mark 9:33-37, and Luke 9:46-48 from this vantage point.

One Twenty-Seven 54 THIRD READING Matthew 18:1-5 Mark 9:33-37 Luke 9:46-48 At that time the disciples came to Jesus, saying, "Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?" And calling to him a child, he put him in the midst of them, and said, "Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. "Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me.” And they came to Caper'na-um; and when he was in the house he asked them, "What were you discussing on the way?" But they were silent; for on the way they had discussed with one another who was the greatest. And he sat down and called the twelve; and he said to them, "If any one would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all." And he took a child, and put him in the midst of them; and taking him in his arms, he said to them, "Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me; and whoever receives me, receives not me but him who sent me." And an argument arose among them as to which of them was the greatest. But when Jesus perceived the thought of their hearts, he took a child and put him by his side, and said to them, "Whoever receives this child in my name receives me, and whoever receives me receives him who sent me; for he who is least among you all is the one who is great."

The Widow and the Orphan 55 Reading this well-known story, it seems to me relevant that the parents of this child are nowhere to be found. I wonder if this child might be an orphan. Let’s read the story accordingly, opening ourselves to new emphases in each of the three versions. Version 1: Matthew In the Matthew version, we may reread the gist of the story through the value of arevut (interconnectedness, experiencing others’ sufferings and joys as your own, mutual responsibility). We may re-hear the fundamental message as: unless you collectively turn toward, experience yourselves anew in, and become like such a lone and lowly child— unless you truly see yourselves in such a child, suffer with this child, and see their sufferings in some way as your own— unless you wish for such a child the kind of reception and care you would wish for a child of your own families, that you would wish for yourselves were you this child— and then from this deep sense of connectedness, collectively receive and care for such children, for this is what it means to do so in my name— then you will not live up to my redemptive hopes for you, alas! Version 2: Mark The Mark version takes place in a house in Caper’naum. Jesus first takes a lone child, then sets the child in the midst of the group, and then picks the child back up, this time cradling the child in his arms. It’s a very deliberate action, one that at first seems to be redundant. Why does Jesus not simply take the child and cradle the child in his arms? Why go through the motion of setting the child in the midst of the group, if he intends to cradle the child in his arms? I wonder whether Jesus here is teaching through a symbolic demonstration. It’s as if he sets the child in the midst of the group to indicate that it takes a village to care for a lone child, to help that child feel safe. (Indeed, the name of the town Caper’naum is likely of Hebrew origin: kfar nahum means “village of consoling/comfort”). Every child deserves a community. Moreover, by proceeding to embrace the child in his arms, Jesus then indicates the import of caring for each lone child, fully, with one-on-one attention, in a house that is secure: spending time with the child individually, offering loving touch to the child, responding to that child’s need for consolation. Every child yearns for such reception and care from a loving parent, just as Jesus’ followers seek such

One Twenty-Seven 56 THIRD READING spiritual reception and care from Jesus himself and from the One who sent him. Every child deserves a family. Version 3: Luke In the Luke version, Jesus takes the lone child and sets the child by his side. Although the text does not specify that Jesus puts the child by his right side, I wonder if we might infer it, given that Jesus is modeling what reception looks like: “Whoever receives this child in my name receives me, and whoever receives me receives him who sent me.” The common verb in Greek “to receive,” déchomai, literally means “to take with the customary hand,” that is, it shares the root of dexiós, which means “right hand, right side.” (In ancient Greek, as well as ancient Hebrew, the right hand/side indicated honor, success, strength, auspiciousness.) In such a scenario, Jesus paints a picture of the lone child as deserving not the least place, but rather the greatest place of honor amongst us, like Christ at the right hand of God. Jesus instructs his followers to see within this most lonely and vulnerable child the divine spirit and the greatest of potential. In essence: may we respond to Jesus’ invitation to serve this child as best we can, as ethically as we can, as reverently as we can, with humility. While some readers might wish to try to harmonize the three versions of the story, I propose that the thrice repetition is profound. The story has been transmitted to us in three ways, so many generations later; perhaps in James’ time, his listeners only knew one version of the story, or perhaps many versions were circulating. In any case, we who are readers of the compiled Christian scriptures nowadays have been given the gift of seeing this lone child over and over again in the scriptures, each time a little bit differently in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Three times, we encounter Jesus’ invitation to uphold a collective sacred responsibility to care for such children. I keep this in mind, therefore, when I read James 1:27: “Religion (thrēskeia) that is pure and undefiled before God and the Father is this: to look-upon-and-care-for orphans and widows in their affliction, and to keep oneself unstained from the world.” I can imagine James saying: OK, my brothers and sisters, you’ve now heard the story three times, you’ve now had some practice seeing, and you’ve now learned some principles for ethical care of lonely children--now you too, go do! And do it over and over again, this thrēskeia, this purest form of ceremonial worship! Of course, it’s not a simple matter to look-upon-and-care-for anyone in their affliction, let alone orphans and widows. It’s tough to look intently, directly, at the harsh realities of our world, over and over again. Even if we are doing the good care that we were created by God to do, living into our Genesis-Us, there