Return to flip book view

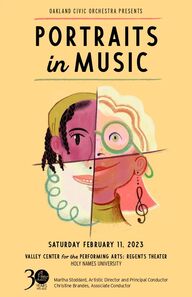

OAKLAND CIVIC ORCHESTRA PRESENTSPORTRAITS in MUSICSATURDAY FEBRUARY 11, 2023VALLEY CENTER for th PERFORMING ARTS: REGENTS THEATERHOLY NAMES UNIVERSITYMartha Stoddard, Artistic Director and Principal ConductorChristine Brandes, Associate Conductor

PLEASE SILENCE ALL CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEFORE THE CONCERT BEGINS.THANK YOU!Darker America (1924)William Grant Still (1895-1978)Two Portraits, Op. 5 (1907-1911)Béla Bartók (1881-1945)1. Idealistic. Andante Sostenuto2. Distorted. PrestoChristina Walton, ViolinINTERMISSIONSymphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 (1885)Antonin Dvořak (1841-1904)I. Allegro Maestoso II. Poco AdagioIII. Scherzo (Vivace)IV. Finale (Allegro)Martha Stoddard, Artistic Director and ConductorChristine Brandes, Associate ConductorPORTRAITS in MUSICDarker America by William Grant Still presented under license from Carl Fischer, copyright owners.

Darker America by William Grant Still presented under license from Carl Fischer, copyright owners.Welcome to the second concert of the Oakland Civic Orchestra’s 30th Anniversary Season, Portraits in Music. Our theme today speaks to the emo-tional nature of music and the powerful expressive range of the orchestra, and we welcome two accomplished artists and beloved colleagues to share in this performance: Associate Conductor Christine Brandes, who leads our first piece, and Concertmaster Christina Walton, as our violin soloist. First, we hear a portrait of the African American experience in the melodic strains of William Grant Still‘s Darker America, in turn depicting sorrow, hope and triumph, and then combining them. In Bartók’s Two Portraits, the composer intentionally paints vividly contrasting pictures, using the same primary melodic motif in both, but to vastly different effect. The first, “Idealistic”, is the violin solo extracted verbatim from the first movement of the composer’s violin concerto, and the second, “Distorted”, seemingly unrelated and quite short, but based on the same motif. The latter is an orchestration of his Bagatelle No. 14 for solo piano. There is a longer story behind this; the two portraits are a reflection of a failed love affair.Dvořak too paints musical pictures, albeit abstractly, in his acclaimed Sym-phony No 7. His most ambitious symphony to date, he sought to establish himself as a serious composer with a highly expressive work. It is interesting to note the inscription on the manuscript: “This main theme occurred to me upon the arrival at the station of the cere-monial train from Pest in 1884.” The train was carrying Czechs from Hungary to Prague for a performance at the National Theater, which was followed by a pro-Czech political demonstration Cast in D minor, the symphony is at turns lyrical, fiery and miltaristic, somber, humorous and playful, with colorful orchestration, a compelling command of or-chestral forces and musical structure, ending with more than a glimmer of hope. – Martha Stoddard, Artistic Director and ConductorFROM the PODIUM

mystical b elia smit

ABOUT our soloistChristina Walton, originally from Greenville, SC, began playing the violin at age ten, attending her hometown’s orchestral and chamber music programs, in-cluding South Carolina Allstate Orchestra as well as Piccolo Spoleto in Charles-ton, SC. In her senior year of high school, she was bitten by the acting bug and went on to earn a BFA in musical theater from Brenau University in Gainesville, GA, and an MFA in acting from the American Conservatory Theater in San Fran-cisco.In recent years, Christina has worked primarily as a freelance musician, playing for musical theater, recordings for indie artists and Stanford Live or-chestral performances. She had the great pleasure of playing in the band for Berkeley Repertory Theater’s world premiere productions of Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations and Paradise Square. Currently, Christina is a member of The Dynamic Miss Faye Carol’s string quartet, performing the re-cently commissioned musical suite “Blues, Baroque and Bars: From the Streets to the Symphony” together with Miss Carol’s jazz trio in venues around the Bay Area.Oakland Civic Orchestra has been Christina’s classical music home since moving to the Bay Area over ten years ago. She is delighted to have the oppor-tunity to perform some of Bartók’s beautifully dissonant solo writing for violin with her peers in the orchestra.

Martha Stoddard assumed the leadership of the Oakland Civic Orchestra in 1997 and has guided the orchestra through a major transformation over the past two decades. Praised for her clarity, generosity, and vision, she continues to lead the orchestra through the unfolding challenges facing our wider community, while continually striving for artistic excellence. Ms. Stoddard is a strong advocate for living composers and has conducted many pre-mieres and commissions in multiple orchestras, most recently featuring works by Jessica Krash and Niko Umar Durr. In 2019 she was named a semi-finalist in the American Prize Competition for Conductors, Community Orchestra Division, and advanced as a finalist in July of 2020. Simultaneously she brought the orchestra into the final round of the Ernst Bacon Prize for the Performance of American Music for their performance of Bruce Reiprich’s Lullaby featuring Christina Owens Walton, violin; J.P. Johnson’s Harlem Symphony; and her own Waltz for the Fun of It.After a lengthy search spanning the course of the pandemic, Ms. Stoddard was recently named Conductor of the Holy Names University Community Orchestra and commenced with her duties in July 2022 at the same time she was appointed Music Director for the Oak-land-based Community Women’s Orchestra. She took the reins as conductor for the new-ly-formed Piedmont Chamber Orchestra in 2019, and held the position of Resident Conductor for Enriching Lives Through Music from 2017-2019. From 2012-2014 she served as Program Director for the John Adams Young Composers Program at the Crowden Music Center and has frequently appeared as Associate Conductor of the San Francisco Composer’s Chamber Orchestra, conducting new works by local composers. She retired from Lick-Wilmerding High School in 2021 after serving for thirty years as Director of Instrumental Music and the Chair of the Performing Arts and is happily filling up her time with more music and more tennis.ABOUT our CONDUCTORS

Following a distinguished international singing career during which she was acclaimed for her radiant, crystalline voice and superb musicianship across a broad repertoire, Christine Brandes takes to the podium as conductor and garners praise for performances in the opera house and on the symphony stage.Ms. Brandes is a 2021-2022 fellow of the Dallas Opera Hart Institute for Women Conductors and currently the Associate Conductor of the Oakland Civic Orchestra. She has led productions of Gluck’s Orfeo et Eurydice and Handel’s Giulio Cesare in Egitto with West Edge Opera as well as Haydn’s Armida and Rameau’s La Sympathie with Victory Hall Opera in Charlottesville, Virginia to which she returns in March of 2023 to conduct Gluck’s Orfeo et Eurydice. Ms. Brandes makes her conducting debut at the Seattle Opera in the fall of 2023 with Handel’s Alcina.On the concert stage, Ms. Brandes made her debut with the San Francisco Chamber Orchestra in the fall of 2022 and her debut performances of Handel’s Messiah with the Virginia Symphony in December of 2022. She has also served as the cover conductor for Nicholas McGegan with the Oakland Symphony.As a singer, she has sung principal roles for the following opera companies: San Francisco, Seattle, Washington National, Houston Grand, Minnesota, New York City Opera, Philadelphia, Glimmerglass, Portland, among others.She has also sung with the following orchestras: Cleveland, Chicago, New York Philharmonic, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Houston, Atlanta, Detroit, Seattle, Minnesota, National Symphony, with such distinguished conductors as Sir Simon Rattle, Pierre Boulez, Esa-Pekka Salonen, and Nicholas McGegan, among many others.To read more about Ms. Brandes please visit: christine-brandesPhoto: Henry Dombey

OCO VENUE AUDIENCE SURVEYOCO VENUE AUDIENCE SURVEYThe Oakland Civic Orchestra needs your opinion!To further meet the needs of our audience please help us plan our future seasons by taking this brief survey.Scan the QR Code below or visit:http://bit.ly/3JVasX6

OCO OCTOBER 2022 concertThanks to Carol DeArment for the photos and videos of this amazing concert! To watch this perfomance visit us on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLszw9l8nYWFzqa7q-JQPXzHorqIQa6QObETap on program to view

OCO MERCHANDISENow available - OCO Logo Merchandise at Redbubble! Enjoy choosing from a variety of items with the OCO Logo emblazened in black or white and donate to OCO at the same time! 20% of the price of each item goes to OCO. The link to the store is on ourwebsite at www.oaklandcivicorchestra.com or visit TheOCO-store directly at Redbubble:TheOCOstore

Check out the OCO website for season updates, future performances and more information on upcoming YouTube video uploads including selections from today’s concert event!www.oaklandcivicorchestra.com

program notes 1William Grant Still, Jr. (1895-1978) • Darker America (1924)William Grant Still, Sr. died shortly after his son’s birth. The boy’s mother, Carrie, moved them to Little Rock, where she taught high-school English. When William Jr. was nine, she remarried, and the stepfather took him to see operettas and bought early classical recordings, which he loved, propelling him to a life in music.Ultimately, he got a scholarship to Oberlin Conservatory, and studied with prominent composers such as George Chadwick and Edgar Varèse. With the mentorship and support of those teachers and others, he became the “Dean of Afro-American Composers,” winning more success than many of his white col-leagues. He was the first African-American to conduct a major American sympho-ny orchestra, the first to have a symphony performed by a leading orchestra (the Rochester Symphony under Howard Hanson, who became one of Still’s boosters), the first to have an opera performed by a major opera company, and the first to have an opera performed on national television.This piece came well before all of that success, from a time he was work-ing in New York, where he was considered part of the Harlem Renaissance. Still arranged popular and jazz music and played in various bands, including the Paul Whiteman orchestra.And he composed. With his background in jazz, steeped in spirituals, gospel, barrelhouse, and especially the blues, Still’s music is unabashedly from this side of the Atlantic, and of the 20th Century. Here is what Still wrote for the program notes at the premiere of this piece:“Darker America, as its title suggests, is representative of the American Negro. His serious side is presented and is intended to suggest the triumph of a people over their sorrows through fervent prayer. At the beginning the theme of the American Negro is announced by the strings in unison. Following a short development of this, the English horn announces the sorrow theme which is followed immediately by the theme of hope, given to muted brass accompanied by string and woodwind. The sorrow theme returns treated differently, indicative of more intense sorrow as contrasted to passive sorrow indicated at the initial appearance of the theme. Again hope appears and the people seem about to rise above their troubles. But sorrow triumphs. Then the prayer is heard (given to oboe); the prayer of numbed rather than anguished souls. Strongly contrasted moods follow, leading up to the triumph and the people near the end, at which point the three principal themes are combined.” Fun fact: longtime journalist and NPR presenter Celeste Headlee (often anchor-ing Here and Now) is a classical soprano…and granddaughter of William Grant Still.

Béla Bartók (1881–1945) • Two Portraits, Op. 5 (1907–1911)The first movement was reworked from his Violin Concerto No. 1, Sz.36. The second movement is an orchestrated version of the fourteenth of the 14 Bagatelles, composed as a piano work in 1908 but not orchestrated until 1911.That simple statement hides the drama behind how this piece came to be. As is often the case, thwarted love played a hand.Bartók probably met Stefi Geyer in about 1902 when he was 21 and she was a 14-year-old violin prodigy. Five years later, Béla had graduated from the Budapest conservatory and was working as a professor of piano there. By this time, Stefi had become the standout violin student at the same institution (and an international star), and the two friends began to play together. Bartók started to write a violin concerto with her in mind…and fell in love.The letters—sadly, we only have his side of the conversation—give us clues as to why it did not work out. In today’s terms, we see that the young Béla was “unclear on the concept,” mansplaining to the devout Catholic Stefi why religion was pointless. One quote says a lot: “If I ever crossed myself, it would signify ‘In the name of Nature, Art and Science…’ Isn’t that enough?!” He even offered to send her reading matter so she could better understand why he was right. Sheesh. But at nineteen, Ms. Geyer was already a strong woman and, though she esteemed him greatly, was not about to play the role of meek muse. She said no.He finished the concerto and sent his only manuscript to her in 1908. She put it in a drawer, and it was never performed in either of their lifetimes. It was unearthed decades later and first performed in 1958. Of course, the music was not lost: the first movement of the concerto is basically identical to the first Portrait you are about to hear. And themes from the second movement appear in one of his first string quartets.That first portrait is labeled “Idealistic.” It’s Bartók’s gentle love song to Stefi Geyer. In form, it resembles a fugue. That is, there is an opening subject, which in this case is a melody that begins with a rising arpeggio characteristic of this movement, a “Stefi motif.” The melody is elusive, though, hard to pin down. It slithers from happiness to angst, changing key or avoiding one altogether. But after the solo violin (it’s Stefi) is done with the theme, a few violinists support her for a bit (some play a countersubject, which appears again later). Then you will hear the same exact theme again, and then again and again, sometimes coming in in a different key; then woodwinds in unison, very soft—you get the idea. Listen for those arpeggios. Notice that there are also parts of arpeggios, sometimes inverted, that help those slithery passages make more sense.Towards the end of the movement, there is a huge climax and then—everybody stops. There is a brief pause, before a coda in which Stefi leads us to Program notes 2

Program notes 3one of the gentlest, most poignant endings in any symphonic piece.The solo violin plays no part in the second movement, which is labeled “Grotesque” or “Distorted.” It’s fast and raucous, a scherzo, a mad waltz, a romp all the way through. Notice that after an 8-bar introduction, the woodwinds enter fortissimo—using the same “Stefi” arpeggio. Is this Bartók’s response to Stefi’s rejection? Perhaps. When he wrote the Bagatelles, the hurt was probably still raw.An observation for fans of the American Songbook: about 30 years after Bartók wrote Two Portraits, Vernon Duke wrote the jazz standard I Can’t Get Started, immortalized by the trumpeter Bunny Berigan. The first seven notes of both pieces are the same. Did Duke know this Bartók piece?Antonin Dvořák (1841–1904) • Symphony No. 7 in D minor Op. 70 (1885)Antonin Dvořák grew up near Prague, in Bohemia in the Austrian Empire. Like so many other famous composers, he showed musical promise at an early age, learning piano, organ, and violin, and studying music theory and beginning to compose. During the 1860s, his twenties, Dvořák played viola (yay! violas!) in the Provisional Theater Orchestra (an odd name for an theater, but not ironic: the building was a stand-in for the Czech National Theater, which was under construction). During this time, he composed a lot of music, but none was published or performed in public. He even composed his first symphony in 1865. In 1871, he left the Provisionals to focus on composition, and took a job as an organist to make ends meet.At this point, let’s consider for a moment how many other European musicians must have been working as viola players or organists, writing string quartets and symphonies on the side. Have you heard of them? No you have not. What turned this one into Dvořák?Gigantic talent, of course. But also relentless determination—and a bit of “it’s who you know.”Antonin got some pieces performed, to modest local acclaim, in 1872. Maybe with that encouragement, he submitted a number of works—including his first symphony—to a competition in Germany. Not only did he not win, but his manuscripts were never returned. Fun story about that: In 1882, when our Dvořák was still not well-known, a young scholar named Rudolf Dvořák—no relation!—saw the score in a secondhand bookshop in Leipzig and bought it, maybe for the coincidence of seeing his name. Perhaps he put it in a drawer—like Bartók’s first violin concerto—because the next we hear of it is in 1923, when Rudolf’s son finds it among the papers he inherited from his father. After extensive authentication,

that symphony was first performed in 1936, and published in 1961.At any rate, Antonin Dvořák was not deterred. He kept writing, and submitted new works the next year to an Austrian prize competition. This batch included two more symphonies (!) and other works. And he won. Unbeknownst to him, one of the very impressed judges was another composer, eight years his senior—but who had yet to write his first symphony—Johannes Brahms.After a few more successful composition prize entries from the young Czech composer, (and after his First Symphony), Brahms made himself known to the [suitably gobsmacked] younger composer and introduced him to his publisher, Simrock. This was the key to becoming known outside of Prague. Dvořák could quit his organ job. This was 1877.Skip ahead to 1883: Dvořák was doing well, working on chamber music and a violin concerto, with six symphonies under his belt. Brahms, meanwhile, had spent the summer working on a new piece. That Fall, he sat down at the piano with his friend Dvořák and played what he had so far. Imagine what it would have been like to be one of the first to hear Brahms’s Third. Gobsmacked again, Dvořák started work on this symphony, his Seventh. Its first performance, in 1885 in London, with the composer conducting, was a huge success.The symphony itself has a traditional four-movement structure.Something to listen for: This symphony is in a minor key. Naïvely, we might think this means that it’s going to be sad. But we have more experience than that! We know that in a fundamentally minor symphony, there will be major themes; whole movements might be in a major key and sound more cheerful or uplifting. But here, the major/minor ambivalence is more profound. Listen to how the mood—happy/sad, joyous/tragic, exultant/depressed—changes from measure to measure, even from note to note. And there are places, such as the opening of the second movement, where calling the mood happy or sad really doesn’t make sense. Throughout this symphony, Dvořák is asking our ears to be more subtle, to accept a wider range of feelings, to hear nuance.And now, more details…The first movement’s opening theme is dark and full of energy. As is often the case with themes from this period, the composer quickly takes the “tune” apart and builds sound and structure out of the pieces. We hear the bouncing rhythms and turns, combined in new ways. The contrasting second theme is more cheerful and dancelike. The movement masterfully combines drama and optimism, with that first theme and its fragments—sometimes in major, sometimes minor—haunting us all the way to its quiet close.The second movement (poco adagio) opens more solemnly, with a chorale Program notes 4

Program notes 5in the winds. The whole thing is beautifully orchestrated, maintaining its contemplative tone, and giving us beautiful, sustained melodies, full of longing—until the mood abruptly becomes more energetic, occasionally hinting at the darkness that we expect from a symphony in a minor key, but calm returns, and peace prevails.For the most part, in this symphony, Dvořák avoids the Slavic sound that was making him famous, but in the scherzo we can hear the rhythms of the Bohemian countryside. This is not a simple, folksy piece, however; you will hear that the trio—ordinarily a short contrasting middle section in a scherzo or minuet—is far more elaborate than usual, almost a movement in itself. The transition back to the opening theme is pretty wild; enjoy the ride!In the finale, Dvořák gives us a wide variety of thematic material, presenting us—as he has done throughout this symphony—with the happy/sad dichotomy, this time leaning heavily towards the tragic. And the ending? The whole cadence sets us up for minor, but at the very end, he pulls a switcheroo and ends on the major chord. – Tim Erickson

Interested in becoming a member of the orchestra? Contact us through our website, see link below. Check out our websitePlease visit the Oakland Civic Orchestra’s website for the latest news on upcoming concerts and projects. You can also nd links to videos from our most recent performances and previous concerts.https://www.oaklandcivicorchestra.comCheck out our own Documentary video and learn about our long history of building community and friendship around a love for playing music. Created by Carol DeArment, our bassist and videographer.Oakland Civic Orchestra Documentaryvisit our website

PLEASE JOIN US! APRIL 30 AMERICANS IN PARIS Umar Durr: World Premiere - OCO Composer-in-Residence Commission Milhaud: Quartre Chanson du Ronsard Raquel Taylor, Soprano Barber: Symphony No. 1 Gershwin: An American in Paris Watch website for complete program details coming soon! www.oaklandcivicorchestra.comSAVE THE DATES! OCO 2022-2023 SEASONOCO Anniversary SeasonThe Celebration Continues!

APRIL 30 AMERICANS IN PARIS Umar Durr: World Premiere - OCO Composer-in-Residence Commission Milhaud: Quartre Chanson du Ronsard Raquel Taylor, Soprano Barber: Symphony No. 1 Gershwin: An American in Paris Watch website for complete program details coming soon! www.oaklandcivicorchestra.comSAVE THE DATES! OCO 2022-2023 SEASONToday’s concert is brought to you by the Oakland Civic Orchestra Association and the Oakland Parks and Recreation Department and is performed by members of the Oakland Civic Orchestra. The Oakland Civic Orchestra was founded in 1992 and is a volunteer community orchestra bringing together musicians of all ages and backgrounds to share in the joy and magic of music-making. For more information about joining the orchestra or about our current season, please visit our website at: https://www.oaklandcivicorchestra.com.You can also nd concert information and current news about the orchestra on Facebook. Search for the Oakland Civic Orchestra and “like” us today!musiciansVIOLIN 1Christina Walton, Concertmaster Priyanka Altman, Asst PrincipalAmanda MokNiko Umar Durr Anne Nesbet Helen Tam Phillip TrujilloHarmony LeeMaureen ParkJeremy MarleyVIOLIN 2 Margaret Wu, PrincipalPaula WhiteVeronica OberholzerAmy GordonNancy Ragle Jules ChoKatie WordenSusan WhiteMichael HagenLynn LaVIOLAThomas Chow, Principal Sara RuschéFelix Chow-KambitschLinda HsiehCody KimElizabeth ProctorDorothy LeeVIOLONCELLOVirgil Rhodius, PrincipalDiane LouieJohn SchroderShannon BowmanChristopher KarachaleDiego Martinez MendiolaKate LauerCONTRABASSCarol DeArment, PrincipalSandy SchniewindMackenzie ConklingFLUTESusanne Rublein, PrincipalDarin TidwellOBOERoger Raphael, PrincipalWendy Shiraki ENGLISH HORNWendy ShirakiCLARINETTom BerkelmanMarcelo MeiraDanielle NapoleonBASS CLARINETTom BerkelmanBASSOONAdam WilliamsElizabeth KelsonFRENCH HORNAlex Strachan, PrincipalAllyson WardAlex StepansDaniel BaoTRUMPETCindy Collins, PrincipalTom DaSilvaRoger DainerTROMBONEMax Walker, PrincipalJereld WingBASS TROMBONEGeorge GaeblerTIMPANIMattijs van MaarenPERCUSSION Ryan GhilaTim EricksonPIANO*Monica Chew*Guest Artist

donate!The Oakland Civic Orchestra is excited to announce the Oakland Civic Orchestra Association (OCOA), our newly formed nonprot public benet corporation. OCOA is now able to accept tax de-ductible donations for the benet of the orchestra. OCOA will support operational needs such as sheet music, instrument rentals, licensing fees and allow the orchestra to expand special projects such as commissioning original compositions. We would greatly appreciate your help to make sure the orchestra not only survives the current pandemic but grows in its service to a community that needs music more than ever.If you have the PayPal app on your mobile device please scan the QR Code below to donate directly or check out our website Support page at:https://www.oaklandcivicorchestra.com/support.htmlWe also gladly accept checks and they can be made payable to:Oakland Civic Orchestra AssociationPlease mail to:OCOA – c/o Daniel Bao1106 Park Avenue, #5Alameda, CA 94501Thanks for your support of OCO!

Oakland Civic Orchestra AssociationBoard MembersLila MacDonald, ChairCarol DeArment, SecretaryDaniel Bao, TreasurerChristopher Karachale, At LargeWendy Shiraki, At LargeAlex Strachan, At LargeMargaret Wu, At LargeDeborah Yates, At LargeacknowledgementsTHANK YOU!Christopher KarachaleLila MacDonaldAlex StepansAlex StrachanDorothy LeeVirgil RhodiusMargaret WuDaniel BaoWendy ShirakiOakland Parks and Recreation FoundationStudio One Art CenterFirst Presbyterian Church of Oakland Christina Walton - Librarian Carol DeArment - Video and photographyWendy Shiraki - Webmaster and graphicsTim Erickson - Program AnnotatorRyan Raphael - Cover Graphic

thank you donors!Title VI COMPLIANCE AGAINST DISCRIMINATION 43CFR 17.6(B) Federal and City of Oakland regulations strictly prohibit unlawful discrimination on the bases of race, color, gender, national origin, age, sexual orientation or AIDS and ARC. Any person who believes he or she has been discriminated against in any program, activity or facility operated by the City of Oakland Oce of Parks and Recreation should write to the Director of Parks and Recreation at 1520 Lakeside Drive, Oakland, CA 94612-4598, or call (510) 238-3092. INCLUSIVE STATEMENT: e City of Oakland Oce of Parks and Recreation (OPR) is fully committed to compliance with provisions of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Please direct all inquiries concerning program and disability accommodations to the OPR Inclusive Recreation Coordinator at (510) 615-5755 or smeans@oaklandnet.com. TDD callers please dial (510) 615-5883.AnonymousPriyanka AltmanDaniel BaoHaley BashShannon BowmanChris BrandesNancy BushThomas ChowCindy CollinsAllan CrossmanRoger DainerThomas DaSilvaCarol DeArmentAyako EnglishTim EricksonStephen FeierabendWilliam FinzerGeorge GaeblerLori GarveyNancy GeimerKeith GleasonAraxi GundelngerVeronica GunnShannon HoustonChristopher KarachaleAkiko KobayashiLynn LaKate LauerDorothy LeeNellie LeeMalinda LennihanRusty LevisPamela LouieLennis LyonLila McDonaldJudith NortonDana OwensMaureen ParkElizabeth ProctorNancy RagleRoger RaphaelVirgil RhodiusPatricia RubleinSusanne RubleinJohn SchroderSteven SheeldWendy ShirakiNicola SkidmoreMartha StoddardAlex StrachanJudy StrachanNina StrachanHoward StrassnerMerna StrassnerDebra TempleFrancis UptonTimothy VollmerDeborah WalkerChristina WaltonPatricia WegnerAdam WilliamsAnna WuMargaret WuDeborah YatesA Big Thank You to our Generous Donors!To join our growing list of supporters please visit our OCO website or check out the PayPal page in this program.