Return to flip book view

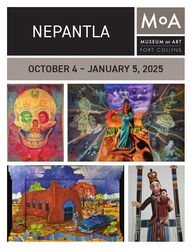

Message 1OCTOBER 4 – JANUARY 5, 2025NEPANTLA

2“Nepantla is a Nahuatl (Aztec language) term which describes being in the middle or the space in the middle. The term was popularized by Chicana writer/scholar Gloria Anzaldua. Most often the term references endangered communities, cultures, or gender[s] who due to colonialism/marginalization or historical trauma... engage in resistance strategies of survival. Nepantla becomes the alternative space in which to live, heal, function, and create.”1 “Nepantla is Nahuatl word for the space between two bodies of water, the space between two worlds. It is a limited space, a space where you are not this or that but where you are changing.”2 You do not yet exist within this new identity, nor have you left the old identity behind; you are in a kind of transition. “And that is what Nepantla [means]. It is a very awkward, uncomfortable, and frustrating place to be because you are amid transformation.”3As you will see throughout this exhibition some artists see Nepantla as a physical place, some see it as a psychological or spiritual space, and others see Nepantla as a personal place. These artists utilize their individual perspectives while creating a unique, rich, and diverse conversation in their art.Nepantla lives in the traditions, politics, and complexities of community. This exhibition focuses on themes of identity, traditions, memory, and struggle. It is furthermore a celebration of the culture and history of Chicanos/Mexican Americans.I selected 36 artists from across the state of Colorado and Northern New Mexico. Within this small microcosm of artists there exists a diversity of ages, sexual orientations, artistic influences, artistic media, and interests. This group of artists is multigenerational, their ages range from between 22 to 80 years old. These artists work in a variety of media: drawing, printmaking, painting, sculpture, mixed media, photography, digital, and AI, among others.The influences on the works of the artists are varied. Some are influenced by the New Mexico Santo tradition. Many of the older artists were part of and influenced by El Movimiento, the Chicano Civil Right Movement of the 1960s and 70s. Many artists are self-taught or learned their craft from fellow or elder artists. Other artists attended art schools or universities and hold BAs, BFAs, MFAs and/or Ph.Ds. With an art education, these artists learned about a variety of artistic movements and traditions, including modern technology such as photoshop, digital art, AI and laser cutting.These artists have researched and studied their indigenous roots and family histories while others credit the teaching of elders who pass on the techniques of caring and painting of the saints. Some of these artists not only create smaller gallery size works of art but also create large public murals throughout the southwest. Many artists are also teachers who have worked in elementary schools, secondary schools, art centers and universities, passing their skills, knowledge, and traditions to others.As you visit this exhibition, take a careful look at the art by these incredible artists. Take a moment to read their statements and look for Nepantla in their work. See if you can come out of this exhibition with a deeper understanding of Nepantla.Tony Ortega, La Marcha de Lupe Liberty, 2006, silkscreen (ed. of 50), 23 x 16 inches1 “About Us,” Nepantla, https://www.nepantlaculturalarts.com/about (Accessed Aug 6, 2024).2 Scott, Charles, and Nancy Tuana. “Nepantla: Writing (from) the In-Between.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 31, no. 1 (2017): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.31.1.0001.3 Scott, Charles, and Nancy Tuana. “Nepantla: Writing (from) the In-Between.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 31, no. 1 (2017): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.31.1.0001.NEPANTLA: A CONTEMPORARY VIEWTony Ortega

3“Nepantla es un término náhuatl (lengua azteca) que describe estar en el medio o el espacio en el medio. El término fue popularizado por la escritora y académica chicana Gloria Anzaldua. La mayoría de las veces, el término hace referencia a comunidades, culturas o géneros en peligro que, debido al colonialismo, la marginación o el trauma histórico... se involucran en estrategias de resistencia para sobrevivir. Nepantla se convierte en el espacio alternativo en el que vivir, sanar, funcionar y crear.”1“Nepantla es la palabra náhuatl que significa el espacio entre dos cuerpos de agua, el espacio entre dos mundos. Es un espacio limitado, un espacio donde no eres esto o aquello, sino donde estás cambiando.”2 Aún no existes dentro de esta nueva identidad, ni has dejado atrás la antigua identidad; estás en una especie de transición. “Y eso es lo que significa Nepantla. Es un lugar muy incómodo, incómodo y frustrante porque estás en medio de una transformación.”3 Como podrá observar a lo largo de esta exposición, algunos artistas ven a Nepantla como un lugar físico, otros como un espacio psicológico o espiritual, y otros como un lugar personal. Estos artistas utilizaron sus perspectivas individuales al tiempo que creaban una conversación única, rica y diversa en su arte.Nepantla vive en las tradiciones, la política y las complejidades de la comunidad. Esta exposición se centra en temas de identidad, tradiciones, memoria y lucha. Además, es una celebración de la cultura y la historia de los chicanos/mexicoamericanos.Yo seleccioné 36 artistas de todo el estado de Colorado y el norte de Nuevo México. Dentro de este pequeño microcosmos de artistas existe una diversidad de edades, orientaciones sexuales, influencias artísticas, medios artísticos e intereses. Este grupo de artistas es multigeneracional, sus edades oscilan entre los 22 y los 80 años. Estos artistas trabajan en una variedad de medios: dibujo, grabado, pintura, escultura, técnica mixta, fotografía, digital e inteligencia artificial, entre otros.Las influencias en las obras de los artistas son variadas. Algunos están influenciados por la tradición de los santos de Nuevo México. Muchos de los artistas más antiguos formaron parte de El Movimiento, el Movimiento Chicano por los Derechos Civiles de los años 60 y 70, y fueron influenciados por él. Muchos artistas son autodidactas o aprendieron su oficio de otros artistas o de artistas mayores. Otros artistas asistieron a escuelas de arte o universidades y tienen licenciaturas, licenciaturas en Bellas Artes, maestrías en Bellas Artes y/o doctorados. Con una educación artística, estos artistas aprendieron sobre una variedad de movimientos y tradiciones artísticas, incluida la tecnología moderna como Photoshop, el arte digital, la inteligencia artificial y el corte láser.Estos artistas han investigado y estudiado sus raíces indígenas e historias familiares, mientras que otros atribuyen el mérito a la enseñanza de los ancianos que transmiten las técnicas de cuidado y pintura de los santos. Algunos de estos artistas no solo crean obras de arte más pequeñas para galerías, sino que también crean grandes murales públicos en todo el suroeste. Muchos artistas también son maestros que han trabajado en escuelas primarias, escuelas secundarias, centros de arte y universidades, transmitiendo sus habilidades, conocimientos y tradiciones a otros.Al visitar esta exposición, observe atentamente el arte de estos increíbles artistas. Tómate un momento para leer sus declaraciones y buscar a Nepantla en su obra. Intenta salir de esta exposición con una comprensión más profunda de Nepantla.Tony Ortega, Super Hombre, 2015, litografia, (ed. of 22) 15 x 20 pulgadas1 “Sobre nosotros”, Nepantla, https://www.nepantlaculturalarts.com/about (consultado el 6 de agosto de 2024).2 Scott, Charles y Nancy Tuana. “Nepantla: escribir (desde) lo intermedio”. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 31, núm. 1 (2017): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.31.1.0001.3 Scott, Charles y Nancy Tuana. “Nepantla: escribir (desde) lo intermedio”. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 31, núm. 1 (2017): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.31.1.0001.NEPANTLA: UNA MIRADA CONTEMPORÁNEATony Ortega

4I am un-Americano. I am Chicano I approach my art from these two perspectives, sometimes at the same time.“Cruzin’ La Grande Jatte in My Classic Chevrolet” is a rather tongue-in-cheek look at two art styles and subjects quite different from one another. In the foreground we see a typical Cholo cruising his ‘Ranfla” (a smooth ride, usually a low rider) while the background is a loose representationGeorges Seurat’spost-impressionist painting“A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” One element is influenced by my Chicanismo, the other by my Americano art pursuits. The juxtaposition of the two makes for the setting of a great place for a weekend cruise.No soy estadounidense. Soy chicano. Abordo mi arte desde estas dos perspectivas, a veces al mismo tiempo.“Cruzin’ La Grande Jatte en mi Chevrolet clásico” es una mirada más bien irónica a dos estilos de arte y temas muy diferentes entre sí. En primer plano vemos a un cholo típico conduciendo su “Ranfla” (un vehículo suave, generalmente de perfil bajo) mientras que el fondo es una representación suetta de la pintura postimpresionista de Georges Seurat “Una tarde de domingo en la isla de La Grande Jatte”. Un elemento está influenciado por mi chicanismo, el otro por mis intereses artísticos estadounidenses. La yuxtaposición de los dos crea el escenario de un gran lugar para un crucero de fin de semana.Cruzin’ La Grande Jatte in My Classic Chevrolet, 2023mixed, acrylic on Masonite, found art20 x 37 x 3½ inchesCruzin’ La Grande Jatte en mi Chevrolet clásico, 2023mixto, acrílico sobre masonita, arte encontrado20 x 37 x 3½ inchesALFREDO CARDENAS

5Encuentros y Mitos Encrucijados (Encounters and Myths at the Crossroads), 2024natural pigments and gesso on wood48 x 35 inchesEncuentros y Mitos Encrucijados, 2024 pigmentos naturales y yeso sobre madera48 x 35 pulgadasJAMES M. CÓRDOVASince colonial times, New Mexico’s santeros (religious art makers) have produced work that strategically combines local and foreign art and design. Santos (painted and sculpted religious art) were made for local devotional purposes and found in New Mexico’s churches, religious chapter houses, and private homes. Because there were no formal art schools in New Mexico, santeros learned their craft in workshops and referenced imported devotional prints, paintings, and sculptures as well as local aesthetics that spanned the hispano and Indigenous worlds. Santeros also worked with and influenced one another, so that older images became learning models for new generations of artists, a phenomenon still evident among New Mexico’s contemporary santeros. The cross-shaped retablo (a two-dimensional santo), “Encuentros y Mitos Encrucijados,” references actual historical painting, cartography and devotional imagery from colonial Latin America and landscape/allegorical painting from the nineteenth-century United States. On the vertical axis, an eighteenth-century map of New Mexico, the first of its kind, features the major Spanish settlements and Indigenous pueblos along the Rio Grande, with Taos and Santa Fe at its northern terminus and El Paso at its southern-most point. A battle between Native warriors and Spanish soldiers speaks of the violence of settler colonialism in New Mexico. The map also bridges the mytho-historical Encounter Between Cortés and Moteuczoma at the bottom of the cross, and the center image of Our Lady of the Macana, a colonial sculpture damaged in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt in which organized Native forces temporarily expelled New Mexico’s hispano population. The actual colonial images upon which these scenes are based, homogenize Indigenous peoples in a manner common to the time and typical in Spanish colonial art. The cross’s horizonal arm references John Gast’s 1872 painting, American Progress, which features an allegorical figure of Progress moving westward as animals and Native peoples flee into an untamed, but vanishing nature. Here New Mexico appears at the crossroads of Spanish colonialism and North American Manifest Destiny, both of which often resulted in violent conflicts in the name of progress and settler colonialism. Desde la época colonial, los santeros de Nuevo México (creadores de arte religioso) han producido obras que combinan estratégicamente el arte y el diseño locales y extranjeros. Los santos (arte religioso pintado y esculpido) se hacían con fines devocionales locales y se encontraban en las iglesias, las salas capitulares religiosas y los hogares casas privados de Nuevo México. Como no había escuelas de arte formales en Nuevo México, los santeros aprendían su oficio en talleres y hacían referencia a grabados, pinturas y esculturas devocionales importadas, así como a la estética local que abarcaba los mundos hispano e indígena.Los santeros también trabajaban y se influenciaban entre sí, de modo que las imágenes más antiguas se convirtieron en modelos de aprendizaje para las nuevas generaciones de artistas, un fenómeno que todavía es evidente entre los santeros contemporáneos de Nuevo México. El retablo en forma de cruz (un santo bidimensional), “Encuentros y Mitos Encrucijados,” hace referencia a la pintura histórica real, la cartografia y a las imágenes devocionales de la América Latina colonial y a la pintura paisajística/alegórica de los Estados Unidos del siglo diecinueve. En el eje vertical, un mapa del siglo dieciocho de Nuevo México, el primero de su tipo, presenta los principales asentamientos españoles y pueblos indígenas a lo largo del Río Grande, con Taos y Santa Fe en su extremo norte y El Paso en su punto más al sur. Una batalla entre guerreros nativos y soldados españoles habla de la violencia del colonialismo de asentamiento en Nuevo México. El mapa también une el encuentro histórico-místico entre Cortés y Moctezuma en la parte inferior de la cruz y la imagen central de Nuestra Señora de la Macana, una escultura colonial dañada en la Rebelión de los Pueblos de 1680 en la que fuerzas nativas organizadas expulsaron temporalmente a la población hispana de Nuevo México. Las imágenes coloniales reales en las que se basan estas escenas homogeneizan a los pueblos indígenas de una manera común en la época y típica del arte colonial español. El brazo horizontal de la cruz hace referencia a la pintura de John Gast de 1872, American Progress, que presenta una figura alegórica del Progreso que avanza hacia el oeste mientras los animales y los pueblos nativos huyen hacia una naturaleza indómita, pero que desaparece. Aquí Nuevo México aparece en la encrucijada del colonialismo español y el Destino Manifiesto norteamericano, ambos a menudo desembocando en conflictos violentos en nombre del progreso y el colonialismo de asentamiento.

6Cyanotype Study of Kincentric Ecologies, 2021cyanotype 72 x 48 inchesEstudio de cianotipia de ecologías kincéntricas, 2021,cianotipia 72 x 48 pulgadasDESERT ARTLAB: CHICANX ENVIRONMENTAL ARTDESERT ARTLAB: ARTE AMBIENTAL CHICANODesert ArtLAB is a Chicanx environmental artist collaborative dedicated to an interdisciplinary art practice exploring connections between ecology, art and community. Their work gives voice and identifies complex political and social dilemmas that reveal themselves in our constructed and natural environments through projects that promote Indigenous/Chicanx perspectives on ecological practice, food sovereignty, self-determination, climate change, and a new understanding of living in the expanding drylands. Grounded in dryland indigenous knowledge systems, Desert ArtLAB’s projects activate public space through participatory artworks and support the restoration of desert ecological systems through zero irrigation regrowth projects. Desert ArtLAB is co-directed by April Bojorquez and Matt Garcia. They live and work in Pueblo, Colorado. The large cyanotypes rethink epistemologies or ways in which knowledge is created and disseminated. In the 19th century, Anna Atkins and other botanists used cyanotypes, a photographic printing method of placing specimens or objects directly onto treated paper and exposing them to light to capture a shadowy image. Desert ArtLAB reinvents the intricate process with environmentally friendly materials, a much larger scale and imagery which moves past a singular research focus. They create large images of desert plants as well as the human figure, connecting our well being with our ability to coexist and sustainably utilize natural resources. The images they create explore Dr. Enrique Salmón’s concept of kincentric ecology - an indigenous concept that recognizes humans and their environment as kin.Desert ArtLAB es una colaboración de artistas ambientales chicanos dedicada a una práctica artística interdisciplinaria que explora las conexiones entre la ecología, el arte y la comunidad. Su trabajo da voz e identifica dilemas políticos y sociales complejos que se revelan en nuestros entornos construidos y naturales a través de proyectos que promueven perspectivas indígenas/chicanas sobre la práctica ecológica, la soberanía alimentaria, la autodeterminación, el cambio climático y una nueva comprensión de la vida en las tierras secas en expansion. Basados en los sistemas de conocimiento indígena de las tierras secas, los proyectos de Desert ArtLAB activan el espacio público a través de obras de arte participativas y apoyan la restauración de los sistemas ecológicos del desierto a través de proyectos de regeneración sin riego. Desert ArtLAB está codirigido por April Bojorquez y Matt García. Viven y trabajan en Pueblo, Colorado.Los grandes cianotipos replantean las epistemologías o las formas en que se crea y difunde el conocimiento. En el siglo diecinueve, Anna Atkins y otros botánicos utilizaron cianotipos, un método de impresión fotográfica que consiste en colocar especímenes u objetos directamente sobre papel tratado y exponerlos a la luz para capturar una imagen sombreada. Desert ArtLAB reinventa el intrincado proceso con materiales respetuosos con el medio ambiente, una escala mucho mayor e imágenes que van más largas de un enfoque de investigación singular. Crean imágenes de gran tamaño de plantas del desierto, así como de la figura humana, conectando nuestro bienestar con nuestra capacidad de coexistir y utilizar de forma sostenible los recursos naturales. Las imágenes que crean exploran el concepto de ecología kincéntrica del Dr. Enrique Salmón, un concepto indígena que reconoce a los humanos y su entorno como parientes.

7DESERT ARTLAB: CHICANX ENVIRONMENTAL ARTDESERT ARTLAB: ARTE AMBIENTAL CHICANOde aqui y de allaceramic, wood, metal, incense, tea, fabric, acrylic paint33 x 18 inchesde aquí y de allácerámica, madera, metal, incienso, té, tela, pintura acrílica33 x 18 pulgadasVICTOR ESCOBEDOA head nod to the original phrase ni de aqui, ni de alla, neither from here, nor from there. The piece entitled de aqui y de alla, from here and from there, is the antithesis of experiencing displacement of two physical places. Instead, it explores the connection of the physical planes of existence to the other worldly, spiritual realm. Divinity incarnate. Humanities physical form manifests through a sacred feminine portal from that place where soul originates. Life is bestowed on to us temporarily and will inevitably return.Un guiño a la frase original ni de aquí, ni de allá. La pieza titulada de aquí y de allá es la antítesis de experimentar el desplazamiento de dos lugares físicos. En cambio, explora la conexión de los planos físicos de la existencia con el otro mundo, el reino espiritual. La divinidad encarnada. La forma física de la humanidad se manifiesta a través de un portal femenino sagrado desde ese lugar donde se origina el alma. La vida se nos otorga temporalmente y regresará inevitablemente.

8The Crowning, 2024linocut 11 x 15 inchesLa coronación, 2024linograbado 11 x 15 pulgadasANGEL ESTRADAOur life experiences are many times shared through photographs about times and people long past. That urge to share is an urge for others to understand a way of living they may have never experienced. It’s a way of showing other people your life without them needing to be there or have known you personally in some way. Looking through photo albums, picture walls and altars in living rooms was the way I learned about people and their families. I wanted to create images that exemplified that experience.Nepantla is a Nahuatl word for “a space between two bodies of water, the space between two worlds.” It is also defined through the scope of being the result or a part of two different sources/cultures, something that changes, not one way or another. I wanted to show this idea through images that were based on my own family photographs placed inside a very traditional craft (Hojalata) that represents Mexican culture where the pictures themselves represent my American experience. This is the result of a mixture and embracing of both sides of the culture.This print represents the idea/feeling of Napantla and the urge to show as well as tell about my experience/life in the United States as a person from a mixed together background. This is an amalgamation of many different influences, references and inspiration. The Southwest of the U.S. is where I have grown up and made my art about in many different ways. I wanted to represent it in a way that involves my lived experience but also the other people and cultures as well. This is the embrace of both cultures that made me into the person I am and how I see the world as well as those around me. Muchas veces compartimos nuestras experiencias de vida a través de fotografías sobre épocas y personas del pasado. Ese deseo de compartir es un deseo de que los demás comprendan una forma de vivir que tal vez nunca hayan experimentado. Es una forma de mostrarle a otras personas tu vida sin que tengan que estar allí o conocerte personalmente de alguna manera. Mirar álbumes de fotos, paredes con cuadros y altares en las salas de estar fue la forma en que yo aprendí sobre las personas y sus familias. Quería crear imágenes que ejemplificaran esa experiencia.Nepantla es una palabra náhuatl que significa “un espacio entre dos cuerpos de agua, el espacio entre dos mundos.” También se define a través del alcance de ser el resultado o parte de dos fuentes/culturas diferentes, algo que cambia, no de una manera u otra. Quería mostrar esta idea a través de imágenes que se basaban en mis propias fotografías familiares colocadas dentro de una artesanía muy tradicional (Hojalata) que representa la cultura mexicana, donde las imágenes en sí mismas representan mi experiencia estadounidense. Este es el resultado de una mixta y aceptación de ambos lados de la cultura.Esta impresión representa la idea/sentimiento de Napantla y la necesidad de mostrar y contar sobre mi experiencia/vida en los Estados Unidos como una persona de origen mixto. Se trata de una amalgama de muchas influencias, referencias e inspiraciones diferentes. El suroeste de los EE. UU. es donde crecí y donde hice mi arte de muchas maneras diferentes. Quería representarlo de una manera que involucrara mi experiencia vivida, pero también a otras personas y culturas. Esta es la aceptación de ambas culturas que me convirtieron en la persona que soy y cómo veo el mundo y a quienes me rodean.

9Ni Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan, 2024acrylic26 x 20 inchesNi Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan, 2024acrílico26 x 20 pulgadasJAVIER FLORESThis piece entitled "Ni Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan," is a tribute to the cultures that have created me. On the left side of the anthropomorphic image of myself is the side clinging to the most recent iteration of our Northern Mexican culture. The world of the Vaquero, or Ranchero (Chero) for short relates to the influence we have in the northern part of Mexico, as well as the southwest of the United States. This is a long-standing lineage from the days of the conquest to the influence on the American Cowboy. Both the side of my mom and dad are heavily influenced by this aesthetic as well as way of life. It directly correlates with the religious as well as patriarchal structures that make up a large part of how I was raised. Contradicting these parts is my near-death experience that landed me in a wheelchair. I could not for the life of me see what I had done that was so bad that it warranted this from God. I took to questioning these components of my life, and having read history from our (Mexican) viewpoint and concluded that I would not continue to support any religion or the patriarchy. The other half represents the very likely mestizo background from the Tarahumara Natives/Raramuri. Having gone to Mexico from a young age, I was constantly introduced to this beautiful indigenous culture. I was and am proud to know of how these two cultures informed me of who I am, as well as knowing that I am not from here or there (Ni Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan), I am the hybrid of both influences mixed with punk rock, hip-hop, and trying to do my best to be a steward for the earth like my indigenous ancestors before me. Borders and boundaries create division, and xenophobia, it is easy to say you are not like me and we have no similarities. However, I believe that we can continue to build a more intersectional world, respecting all for their differences, and where we have commonality. Esta pieza titulada "Ni Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan," es un homenaje a las culturas que me han creado. En el lado izquierdo de la imagen antropomórfica de mí mismo yo se encuentra el lado que se aferra a la iteración más reciente de nuestra cultura del norte de México. El mundo del Vaquero, o Ranchero (Chero para abreviar), se relaciona con la influencia que tenemos en la parte norte de México, así como en el suroeste de los Estados Unidos. Este es un linaje de larga data desde los días de la conquista hasta la influencia del vaquero estadounidense. Tanto el lado de mi madre como el de mi padre están fuertemente influenciados por esta estética y estilo de vida. Se correlaciona directamente con las estructuras religiosas y patriarcales que conforman una gran parte de cómo me criaron. Contradiciendo estas partes está mi experiencia cercana a la muerte que me dejó en silla de ruedas; no podía ver por mi vida qué había hecho que fuera tan malo como para justificar esto de parte de Dios. Comencé a cuestionar estos componentes de mi vida y, después de leer la historia desde nuestro punto de vista (mexicano), concluí que no seguiría apoyando ninguna religión ni el patriarcado. La otra mitad representa el muy probable origen mestizo de los nativos tarahumaras/rarámuri. Habiendo ido a México desde una edad temprana, me presentaron constantemente esta hermosa cultura indígena. Estaba y estoy orgullosa de saber cómo estas dos culturas me informaron sobre quién soy, así como de saber que no soy de aquí ni de allá (Ni Muy Muy, Ni Tan Tan), soy el híbrido de ambas influencias mezcladas con punk rock, hip-hop y tratando de hacer mi mejor esfuerzo para ser un administrador de la tierra como mis antepasados indígenas antes que yo. Las fronteras y los límites crean división y xenofobia, es fácil decir que no eres como yo y que no tenemos similitudes. Sin embargo, creo que podemos seguir construyendo un mundo más interseccional, respetando a todos por sus diferencias y donde tenemos cosas en común.

10Nepantlacoatl, 2024concrete and structural mortar18 × 9 × 4 inchesNepantlacoatl, 2024concreto y estructural mortero18 × 9 × 4 pulgadasDIEGO FLOREZ-ARROYOThis concrete work is inspired by the paradox of the Chicano experience. On one side the indigenous ancestry on the other we are met with a wall. Using this imagery as a symbolic metaphor for Nepantla. We are one and the other. Held together by only gravity stacked upon each other we see the fragility of the wall always with a potential to be broken, while also an opportunity to build the strength of our bond with our history, culture, and tradition.Esta obra de concreto está inspirada en la paradoja de la experiencia chicana. De un lado, la ascendencia indígena y del otro, nos encontramos con una pared. Utilizando esta imagen como metáfora simbólica de Nepantla. Somos uno y el otro. Unidos únicamente por la gravedad, apilados uno sobre el otro, vemos la fragilidad de la pared, que siempre tiene el potencial de romperse avebrarse, pero también es una oportunidad para fortalecer nuestro vínculo con nuestra historia, cultura y tradición.

11Nepantla, 2024 acrylic on unstretched canvas9 x 6 feetNepantla, 2024acrílico sobre lienzo sin estirar9 x 6 piesCARLOS FRÉSQUEZ I grew up in Denver CO, in the heart of the 1960’s and 1970’s Chicano Movement, known as “El Movimiento”. My first protest was on September 16, 1969, I was 13 years old. It is around this time that I became politically and culturally aware of who I am and what direction I want to go in life. As a Chicano, or Mexican- American, I have always felt that I am living on the hyphen, a place between a Mexican and being an American. The hyphen is a metaphor; I am straddling a circus high wire doing my best to keep moving forward while using the hyphen as a balancing pole, walking and living in the middle.I began making art or creating at a very young age. I recently had my DNA looked at and found that I am approximately 50% of the indigenous peoples of northern New Mexico and of 50% European ancestry. In creating my artwork I have strived to make work that documents my dual life experiences. Back in the early 1990’s I first heard of the word Nepantla and researched it’s meaning. I realized that I have been living and existing in Nepantla my whole life. As a child I recall eating a Hostess Twinkie and eating pan dulce. Growing up in our home, I would listen to the music that my parents played, like Pedro Infante and Lucha Villa. Then I would go to my bedroom and play and listen to Led Zeppelin and The Clash. Years ago, I was reading my son’s comic books, then a few minutes later I was deep in a book about the Aztec Codices. Living in a dual world is where I have always existed.Crecí en Denver, Colorado, en el corazón del Movimiento Chicano de los años 1960 y 1970, conocido como “El Movimiento”. Mi primera protesta fue el 16 de septiembre de 1969, tenía 13 años. Fue en ese tiempo cuando tomé conciencia política y cultural de quién soy y qué dirección quiero tomar en la vida. Como chicano o mexicano-estadounidense, siempre he sentido que vivo en el guión, un lugar entre ser mexicano y ser estadounidense. El guión es una metáfora; estoy a horcajadas sobre la cuerda floja de un circo haciendo todo lo posible por seguir avanzando mientras uso el guión como un palo de equilibrio, caminando y viviendo en el medio.Empecé a hacer arte o a crear a una edad muy temprana. Hace poco me analizaron el ADN y descubrí que pertenezco aproximadamente al 50% de los pueblos indígenas del norte de Nuevo México y al 50% de ascendencia europea. Al crear mis obras de arte, me he esforzado por hacer un trabajo que documente mis experiencias de vida duales.A principios de los años 90 escuché por primera vez la palabra Nepantla e investigué su significado. Me di cuenta de que he vivido y existido en Nepantla toda mi vida. De niño recuerdo comer un Twinkie de Hostess y comer pan dulce. Al crecer en nuestra casa, escuchaba la música que ponían mis padres, como Pedro Infante y Lucha Villa. Luego iba a mi habitación y escuchaba a Led Zeppelin y The Clash. Hace años, estaba leyendo los cómics de mi hijo y, unos minutos después, estaba inmerso en un libro sobre los códices aztecas. Vivir en un mundo dual es donde siempre he existido.

12Our Lady of Guadalupe, 2024 natural pigment, varnish on pine wood20 x 13 ½ inchesNuestra Señora de Guadalupe, 2024pigmento natural, barniz sobre madera de pino20 x 13 ½ pulgadasLYNN FRÉSQUEZI work mainly in the Spanish Colonial Art tradition, carving and painting retablos and bultos in the New Mexico style. I was born and raised in Denver, Colorado. I started drawing at a very young age, but I did not plan on becoming an artist. I am mostly self-taught, but I have taken several art classes at Arapahoe Community College.My first serious artwork was a rather large grid-like acrylic painting of Cesar Chavez, it was painted in the manner of Chuck Close. With this painting, I learned how to develop a concept, use a variety of painting techniques and grasp and experience basic color theory. That painting was my stepping stone into the art world. I started to explore a variety of mediums, from pastels, charcoal, to watercolor and gouache. From there I joined Denver’s, Chicano Humanities and Arts Council Gallery, CHAC. My very first exhibit was at CHAC Gallery.It is at this point, around 2002, that I began my interest in painting retablos, it has become my passion and my spiritual journey. I am mostly self-taught with retablos and bultos. I began to research the life works of historic santeros (saint-makers) and also learning from other contemporary santero artists. I have been blessed on this journey with the help of people who have encouraged me to continue carving and painting retablos. I am married to artist Carlos Frésquez, he has been my mentor and rock. My mentors in santero art have been Teresa Duran, Jose Esquibel, Carlos Santistevan and Frank Zamora. Part of santero artmaking are bultos; I have learned how to carve saints out of wood. I was in an art group of women called “Chicks With Knives”, taught by Judy Miranda. Judy taught us a variety of carving techniques.The paint medium I use are natural pigments over gesso on wood.Trabajo principalmente en la tradición del arte colonial español, tallando y pintando retablos y bultos al estilo de Nuevo México. Nací y crecí en Denver, Colorado. Empecé a dibujar a una edad muy temprana, pero no tenía pensado convertirme en artista. Soy mayormente autodidacta, pero he tomado varias clases de arte en Arapahoe Community College.Mi primera obra de arte seria fue una pintura acrílica bastante grande en forma de cuadrícula de César Chávez, fue pintada al estilo de Chuck Close. Con esta pintura, aprendí a desarrollar un concepto, a utilizar una variedad de técnicas de pintura y a comprender y experimentar la teoría básica del color. Esa pintura fue mi primer pasos hacia el mundo del arte. Empecé a explorar una variedad de medios, desde pasteles, carboncillo, hasta acuarela y gouache. A partir de ahí, me uní a la Galería CHAC del Consejo de Artes y Humanidades Chicanas de Denver. Mi primera exhibición fue en la Galería CHAC. Es en este punto, alrededor de 2002, que comenzó mi interés en pintar retablos, se ha convertido en mi pasión y mi viaje espiritual. Soy principalmente autodidacta con retablos y bultos. Empecé a investigar las obras de vida de santeros históricos (creadores de santos) y también a aprender de otros artistas santeros contemporáneos. He sido bendecida en este viaje con la ayuda de personas que me han animado a seguir tallando y pintando retablos. Estoy casada con el artista Carlos Frésquez, él ha sido mi mentor y mi apoyo. Mis mentores en el arte santero han sido Teresa Durán, José Esquibel, Carlos Santistevan y Frank Zamora. Parte del arte santero son los bultos; he aprendido a tallar santos en madera. Estuve en un grupo de arte de mujeres llamado “Chicas con Cuchillo”, impartido por Judy Miranda. Judy nos enseñó una variedad de técnicas de tallado. El medio de pintura que utilizo son pigmentos naturales sobre yeso sobre madera.

13Home Won’t Know Me, 2021 inkjet photograph36 x 24 inchesEl hogar no me conocerá, 2021 chorro de tinta fotografía36 x 24 pulgadasJUAN FUENTESSelf-taught photographer, Juan Fuentes, was born in Chihuahua, Mexico in 1990. He now works and lives in Denver, Colorado. For the past 8 years his photographs capture topics such as intimate stories of everyday life of immigrants and Chicanos in the Southwest, U.S. Utilizing photographs, Juan examines the visual and emotional artifacts of memory, erasure, and family - creating records that affirm and center marginalized communities.Nepantlais a place that most, if not all, immigrants exist in and with the works titled “Home Won’t Know Me” and“Deteniendo LosAños”, Juan looksat his own story of migration and his experience living as an undocumented migrant in the U.S. “Home Won’t Know Me” is a self-portrait holding a framed photo of his grandpa, who was the first person out of his family to migrate to the U.S. from Chihuahua, Mexico in the early 80’s. In this image he captures the feeling ofthe perpetual in-betweenness that comes with having two different places to call home and the feeling of never fully belonging to neither one of them. “Deteniendo Los Años” is a portraitof his grandparents outside of their home in Denver. While his grandparents are now citizens, the longing for home has not changed andNepantlais still a place that they exist in.Photos by Fuentes are part of the archives at the University of Colorado in Boulder, Regis University, the permanent collection of the Denver Art Museum, the permanent collection of History Colorado Center, and are part of the Abarca Family Collection, housed at the Latino Cultural Arts Center. Working primarily with still images, his artwork also includes installations, murals, books, film, and archives.El fotógrafo autodidacta Juan Fuentes nació en Chihuahua, México, en 1990. Actualmente trabaja y vive en Denver, Colorado. Durante los últimos 8 años, sus fotografías capturan temas como historias íntimas de la vida cotidiana de inmigrantes y chicanos en el suroeste de los EE. UU. Utilizando fotografías, Juan examina los artefactos visuales y emocionales de la memoria, el borrado y la familia, creando registros que afirman y centran a las comunidades marginadas.Nepantla es un lugar en el que viven la mayoría de los inmigrantes, si no todos, y con las obras tituladas “El hogar no me conocerá” y “Deteniendo Los Años”, Juan analiza su propia historia de migración y su experiencia de vida como migrante indocumentado en los EE. UU. “El hogar no me conocerá” es un autorretrato que sostiene una foto enmarcada de su abuelo, quien fue la primera persona de su familia en migrar a los EE. UU. desde Chihuahua, México, a principios de los 80. En esta imagen, captura la sensación de estar en un punto intermedio perpetuo que implica tener dos lugares diferentes a los que llamar hogar y la sensación de no pertenecer nunca del todo a ninguno de ellos. “Deteniendo los años” es un retrato de sus abuelos fuera de su casa en Denver. Si bien sus abuelos ahora son ciudadanos, el anhelo por el hogar no ha cambiado y Nepantla sigue siendo un lugar en el que existen.Las fotografías de Fuentes forman parte de los archivos de la Universidad de Colorado en Boulder, la Universidad Regis, la colección permanente del Museo de Arte de Denver, la colección permanente del Centro de Historia de Colorado y forman parte de la Colección de la Familia Abarca, que se encuentra en el Centro de Artes Culturales Latino. Trabaja principalmente con imágenes fijas, pero su obra de arte también incluye instalaciones, murales, libros, películas y archivos.

14Edge of Daylight, 2024acrylic on canvas39 x 39 inchesBorde de la luz del día, 2024acrílico sobre lienzo39 x 39 pulgadasANTHONY GARCIA, SR.Anthony Garcia, Sr. was born and raised in Denver, Colorado, more specifically in the Globeville community. His artistic style incorporates traditional Chicano motifs and celebrates the complex duality of living as a US Citizen who is also Chicano. His aesthetic pays homage to cultural, geographical, and historical contexts through the implementation of modern techniques and the exploration of pop trends.Anthony Garcia, Sr. nació y creció en Denver, Colorado, más específicamente en la comunidad de Globeville. Su estilo artístico incorpora motivos chicanos tradicionales y celebra la compleja dualidad de vivir como ciudadano estadounidense que también es chicano. Su estética rinde homenaje a contextos culturales, geográficos e históricos a través de la implementación de técnicas modernas y la exploración de tendencias pop.

15I am currently a student at Regis University studying Visual Arts and Art History. I am passionate about many forms of art but specifically practice printmaking the most. Most of the pieces have multiple processes like linocuts and dry points but the main method I use is monotypes. Along with those processes I often use clothing and lace. Stories that are important to me are frequently what I make my prints about. The stories can be from any moment of my life; past, present, or future. Color and expressive lines are important in capturing and conveying stories I cherish. Clothing just like printmaking is a form of expression that can say and show so much about a person. Clothing carries memories and stories. In some of my prints, I am using some of the few pieces of clothing I have from when I was a baby to show how our childhood impacts who we are today more than we think.Actualmente soy estudiante de Artes Visuales e Historia del Arte en la Universidad Regis. Me apasionan muchas formas de arte, pero específicamente practico el grabado. La mayoría de las piezas tienen múltiples procesos como linograbados y punta seca, pero el método principal que utilizo son los monotipos. Junto con esos procesos, a menudo uso ropa y encaje. Las historias que son importantes para mí son con frecuencia sobre las que hago mis grabados. Las historias pueden ser de cualquier momento de mi vida: pasado, presente o futuro. El color y las líneas expresivas son importantes para capturar y transmitir historias que aprecio. La ropa, al igual que el grabado, es una forma de expresión que puede decir y mostrar mucho sobre una persona. La ropa transmite recuerdos e historias. En algunos de mis grabados, utilizo algunas de las pocas prendas que tengo de cuando era bebé para mostrar cómo nuestra infancia impacta en quiénes somos hoy más de lo que creemos.Niñes, 2023monotype43½ x 30 inchesNiñes, 2023monotipo43½ x 30 pulgadasADA GONZALEZ

16Diva, 2024Diasec face mount acrylic giclée print26 x 48 inchesDiva, 2024impresión giclée acrílica con montaje facial de Diasec26 x 48 pulgadasQUINTIN GONZALEZ My most current artwork is an exploration of the intersections of Chicana/o Art, Artificial Intelligence Art, and Visual Culture. It unravels narratives that celebrate cultural identity, technological innovation, and the power of visual expression. This approach, born from a transformative movement, challenges social norms and embraces cultural autonomy. It radiates resilience and self-determination, influenced by diverse artistic traditions and rooted in the Chicanx experience.I explore possible dystopian futures, utopian worlds, and current social struggles, as well as cultural values that shape Chicanx’s collective identity. By adopting Artificial Intelligence Assisted Art, I seek to disrupt the racist implicit bias within the American collective gaze from our history and the current reality of the era in which we live and to show a vision of Chicanas and Chicanos in alternative roles that empower with depictions of a glorious future and speculative fictional dystopian alternate worlds.The convergence of Chicana/o Art, AI Art, Digital Art, and Visual Culture becomes a testament to the ever-evolving nature of artistic expression. Through my work, I endeavor to foster dialogue, inspire connection, and cultivate a more inclusive creative landscape. Honoring diverse histories, embracing technological advancements, and unraveling the broader intricacies of Latinx visual culture, I seek to shed light on our shared human experience and empower the voices that have at times, remained invisible.Lastly, in my depictions of the future or alternate worlds, I explore the grand questions: What will the future hold for the Chicanx? Will it be a dystopian or utopian world, or perhaps a blend of both, and for whom will it be so? Moreover, will my culture’s rich past continue to be relevant? While I cannot claim to have all the answers, I choose to answer my inquiries by depicting my hopes and at times, my fears.Mi obra de arte más actual es una exploración de las intersecciones del arte chicano/a, el arte de la inteligencia artificial y la cultura visual. Revela narrativas que celebran la identidad cultural, la innovación tecnológica y el poder de la expresión visual. Este enfoque, nacido de un movimiento transformador, desafía las normas sociales y abraza la autonomía cultural. Irradia resiliencia y autodeterminación, influenciado por diversas tradiciones artísticas y arraigado en la experiencia chicana.Exploro posibles futuros distópicos, mundos utópicos y luchas sociales actuales, así como valores culturales que dan forma a la identidad colectiva chicana. Al adoptar el arte asistido por inteligencia artificial, busco interrumpir el sesgo racista implícito dentro de la mirada colectiva estadounidense de nuestra historia y la realidad actual de la era en la que vivimos y mostrar una visión de las chicanas y los chicanos en roles alternativos que empoderan con representaciones de un futuro glorioso y mundos alternativos distópicos ficticios especulativos.La convergencia del arte chicano/a, el arte con inteligencia artificial, el arte digital y la cultura visual se convierte en un testimonio de la naturaleza en constante evolución de la expresión artística. A través de mi trabajo, me esfuerzo por fomentar el diálogo, inspirar la conexión y cultivar un paisaje creativo más inclusivo. Honrando las diversas historias, abrazando los avances tecnológicos y desentrañando las complejidades más amplias de la cultura visual latina, busco arrojar luz sobre nuestra experiencia humana compartida y empoderar las voces que, a veces, han permanecido invisibles.Por último, en mis representaciones del futuro o de mundos alternativos, exploro las grandes preguntas: ¿Qué deparará el futuro a los chicanos? ¿Será un mundo distópico o utópico, o tal vez una mezcla de ambos, y para quién será así? Además, ¿seguirá siendo relevante el rico pasado de mi cultura? Si bien no puedo afirmar que tengo todas las respuestas yo, elijo responder a mis preguntas representando mis esperanzas y, a veces, mis miedos.

17La Conciencia De Una Mestiza, 2024textiles38 x 25 x 1 inch each apronLa Conciencia De Una Mestiza, 2024textiles 38 x 25 x 1 pulgada cada delantalLIZETH GUADALUPE “La Conciencia De Una Mestiza” is the relationship between ancestral and contemporary worlds colliding through aprons. Each apron symbolizes caretaking, love of sharing, and expected gender roles within those communities. Being a first-generation Mexican American woman in the US, we learn to code-switch between two worlds. A world where we need to speak Spanish to connect with elders and a world where you assimilate to the colonizers. The apron on the left depicts the ancestral world where married women became the matriarch of the family. The apron on the right is the contemporary world where education is a top priority and we are given more options and choices in our lives. While the middle is the blending of both cultures within our family structures, gathering specific aspects of both cultures and owning who we are meant to become. “La Conciencia De Una Mestiza” binds us to the idea of interrelated materials and aesthetics that relate to the specific region that our ancestors are from, even in contemporary society.“La Conciencia De Una Mestiza” es la relación entre mundos ancestrales y contemporáneos que chocan a través de delantales. Cada delantal simboliza el cuidado, el amor por compartir y los roles de género esperados dentro de esas comunidades. Al ser una mujer mexicoamericana de primera generación en Estados Unidos, aprendemos a cambiar de código entre dos mundos. Un mundo donde necesitamos hablar español para conectarnos con los mayores y un mundo donde te asimilarás a los colonizadores. El delantal de la izquierda representa el mundo ancestral donde la mujer casada se convertía en matriarca de la familia. El delantal de la derecha es el mundo contemporáneo donde la educación es una máxima prioridad y tenemos más opciones y elecciones en nuestras vidas. Mientras que el medio es la combinación de ambas culturas dentro de nuestras estructuras familiares, reuniendo aspectos específicos de ambas culturas y reconociendo quiénes estamos destinados a ser. “La Conciencia De Una Mestiza” nos une a la idea de materiales y estéticas interrelacionados que se relacionan con la región específica de donde provienen nuestros antepasados, incluso en la sociedad contemporánea.

18Youth of America, 2024 ink and colored pencil on paper 14 x 11 inchesJuventud de América, 2024tinta y lápiz de color sobre papel14 x 11 pulgadasKIMBERLY GUTIERREZI was born in El Paso, Texas and raised in Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua; just like my two older brothers. We were sent to schools in the United States, raised in a mixture of American and Mexican culture, are bilingual, and were accustomed to crossing the border every day. My brothers are 11 and 10 years older than me. They are Millennials and I am Generation Z. As of writing this in June 2024, my brothers are 37 and 36. They live in Germany and Florida. One is single and the other is married with children. I am 26 and live alone in Colorado. We are similar in many ways but sometimes seem to have more differences between us. This comes as no surprise considering the worlds we grew up in and the paths we chose in life. There is and always has been space between us, both literal and figurative. My pieces are simple portraits of us growing up in the frontera. However, I find that they are perfect in visualizing what Nepantla means to me and what it felt like growing up in a space shared by multiple generations. I often felt like a child lost in time. I felt totally out of touch with my peers and was often called “an old soul.” I grew up having brothers but they always felt out of reach. My friends were close to their siblings in age or through a special bond. Finding this with my brothers has always felt challenging. I often feel like I’m trying to catch up, doing the same things they had done a decade earlier. Trying to find ways to relate can be difficult when one of you is saving for a house and the other is saving for a video game console. There is and always has been space between us. For me, this space is also felt in interactions where I realize I’m too American to be Mexican and am too Mexican to be American. I’m too mature to relate to people my own age, yet too immature to relate to people older than me. What do you do with these feelings? Who do you talk to? How do you fill that space? How do you make sense of it? How do you express yourself? I try to find answers through my art, hoping it’s enough to close the space between us. Nací en El Paso, Texas y crecí en Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua; al igual que mis dos hermanos mayores. Fuimos enviados a escuelas en los Estados Unidos, crecimos en una mezcla de cultura estadounidense y mexicana, somos bilingües y estábamos acostumbrados a cruzar la frontera todos los días. Mis hermanos son 11 y 10 años mayores que yo. Ellos son Millennials y yo soy de la Generación Z. Al momento de escribir esto en junio de 2024, mis hermanos tienen 37 y 36 años. Viven en Alemania y Florida. Uno es soltero y el otro está casado y tiene hijos. Yo tengo 26 años y vivo sola en Colorado. Somos similares en muchos aspectos, pero a veces parece que tenemos más diferencias entre nosotros. Esto no es una sorpresa considerando los mundos en los que crecimos y los caminos que elegimos en la vida. Hay y siempre ha habido espacio entre nosotros, tanto literal como figurativamente.Mis piezas son retratos simples de nosotros creciendo en la frontera. Sin embargo, encuentro que son perfectos para visualizar lo que significa Nepantla para mí y cómo me sentí al crecer en un espacio compartido por múltiples generaciones. A menudo me sentía como un niño perdido en el tiempo. Me sentía totalmente fuera de contacto con mis compañeros y a menudo me llamaban “un alma vieja”. Crecí teniendo hermanos, pero siempre me sentí fuera de mi alcance. Mis amigos eran cercanos a sus hermanos en edad o a través de un vínculo especial. Encontrar esto con mis hermanos siempre me ha resultado un desafío. A menudo siento que estoy tratando de ponerme al día, haciendo las mismas cosas que ellos habían hecho una década antes. Tratar de encontrar formas de relacionarse puede ser difícil cuando uno de ustedes está ahorrando para una casa y el otro está ahorrando para una consola de videojuegos. Hay y siempre ha habido espacio entre nosotros.Para mí, este espacio también se siente en las interacciones donde me doy cuenta de que soy demasiado estadounidense para ser mexicano y demasiado mexicano para ser estadounidense. Soy demasiado maduro para relacionarme con personas de mi misma edad, pero demasiado inmaduro para relacionarme con personas mayores que yo. ¿Qué haces con estos sentimientos? ¿Con quién hablas? ¿Cómo llenas ese espacio? ¿Cómo le das sentido a todo esto? ¿Cómo te expresas? Intento encontrar respuestas a través de mi arte, con la esperanza de que sea suficiente para cerrar la brecha que nos separa.I Feel Seen, 2024acrylic on canvas25 ½ x 25 ½ inches (2)Me siento visto, 2024 acrílico sobre lienzo25 ½ x 25 ½ pulgadas (2)

19I Feel Seen, 2024acrylic on canvas25 ½ x 25 ½ inches (2)Me siento visto, 2024 acrílico sobre lienzo25 ½ x 25 ½ pulgadas (2)VERÓNICA HERRERAThis diptych focuses on the superficial judgment and discrimination people can have for one another based on skin color, race, occupation, economic status, accent, gender, age, ability, and beliefs and the resulting negative introspection that can have lasting harmful effects on mental health.With social media adding a layer of judgment and need for acceptance, these paintings depict an exchange of emoticon comments. The large, colorful emojis convey the weight that approvals carry. Playful icons are common responses to funny social media posts, but they also symbolize the act of making fun of someone, and the use of humor to mask negative feelings.The blue backgrounds represent common web browser color options, and the transparent self-portraits represent anonymity online as well as their cyber existence. While one face looks upward in an almost idolizing manner, the other face looks down on the viewer with a critical gaze. This visual motion from the viewer to each face creates a back-and-forth motion that simulates up and down scrolling on a mobile device.It is my hope that these paintings create a moment for the viewer to pause and reflect on the positive, personal impact they can have on others and encourage acceptance and equal treatment for all.Este díptico se centra en el juicio superficial y la discriminación que las personas pueden tener entre sí en función del color de piel, la raza, la ocupación, el estado económico, el acento, el género, la edad, la capacidad y las creencias, y la introspección negativa resultante que puede tener efectos nocivos duraderos en la salud mental.Con las redes sociales agregando una capa de juicio y necesidad de aceptación, estas pinturas representan un intercambio de comentarios con emoticones. Los emojis grandes y coloridos transmiten el peso que conllevan las aprobaciones. Los íconos divertidos son respuestas comunes a publicaciones divertidas en las redes sociales, pero también simbolizan el acto de burlarse de alguien y el uso del humor para ocultar sentimientos negativos.Los fondos azules representan las opciones de color comunes de los navegadores web y los autorretratos transparentes representan el anonimato en línea, así como su existencia cibernética. Mientras que una cara mira hacia arriba de una manera casi idolatrante, la otra cara mira hacia abajo al espectador con una mirada crítica. Este movimiento visual del espectador a cada cara crea un movimiento de ida y vuelta que simula el desplazamiento hacia arriba y hacia abajo en un dispositivo móvil. Mi esperanza es que estas pinturas creen un momento para que el espectador se detenga y reflexione sobre el impacto positivo y personal que pueden tener en los demás y fomenten la aceptación y la igualdad de trato para todos.

20Charco (Puddle; Ripple Effect), 2024 oil and collage on panel 36 x 36 inchesCharco (Charco; efecto de ondulación), 2024 óleo y collage sobre tabla 36 x 36 pulgadasEMILIO LOBATO Over the past 7 years I’ve had the privilege of spending one month each year immersed in my art on the Oregon Coast. This artist-in-residence of my own design has been incredibly fruitful and coincidentally, focused on “the space between”. My first encounter of the Oregon coast was as a yearly tourist. Since those days beginning in the mid 80’s, I’ve been intrigued by the phenomenon where land meets water, and then, meets the sky. In winters ‘fog and rainy conditions the in between meld, and all these components of land, sea, and sky seemingly become one. It’s mysterious and disorienting all at once. What is stabilizing is the constant ebb and flow of the ocean waves. The persistent waves are both soothing and mesmerizing. In the past 7 years I’ve produced three distinct bodies of work specifically exploring what I experience (and what I observe) that a coastline induces in the people who visit.My newest body of work is subtitled “Ripple Effect”. Pastel, charcoal and oil on vintage topographical maps depict stones and ripples. Metaphorically they could be people, time, or space. Concentrated energy, attracting and repelling. Like stones dropped in water, this cause and effect is not always seen or even felt, but is there, nonetheless. The auras or waves surrounding these “rocks” is energy, which is constantly moving, intersecting, waxing, and waning. Similarly, the rocks in a Zen Garden mimic that as well. The space between continues to intrigue and inspire.Durante los últimos 7 años he tenido el privilegio de pasar un mes al año inmerso en mi arte en la costa de Oregón. Esta residencia artística de mi propio diseño ha sido increíblemente fructífera y, casualmente, se ha centrado en “el espacio intermedio”. Mi primer encuentro con la costa de Oregón fue como turista anual. Desde aquellos días, a mediados de los 80, me ha intrigado el fenómeno en el que la tierra se encuentra con el agua y, luego, con el cielo. En invierno, la niebla y las condiciones lluviosas se fusionan, y todos estos componentes de la tierra, el mar y el cielo parecen convertirse en uno solo. Es misterioso y desconcertante a la vez. Lo que estabiliza es el flujo y reflujo constante de las olas del mar. Las olas persistentes son a la vez relajantes y fascinantes. En los últimos 7 años he producido tres cuerpos de trabajo distintos que exploran específicamente lo que experimento (y lo que observo) que una costa induce en las personas que la visitan.Mi último trabajo se subtitula “Efecto de onda”. Pastel, carboncillo y óleo sobre mapas topográficos antiguos representan piedras y ondas. Metafóricamente podrían ser personas, tiempo o espacio. Energía concentrada, que atrae y repele. Como las piedras arrojadas al agua, esta causa y efecto no siempre se ve o se siente, pero está ahí, de todos modos. Las auras u ondas que rodean estas “piedras” son energía, que está en constante movimiento, entrecruzándose, creciendo y menguando. De manera similar, las piedras en un jardín zen también imitan eso. El espacio entre ellas continúa intrigando e inspirando.

21Creation Lot 20, 2023 acrylic marker, archival ink pen on recycled paper48 x 48 inchesLote de creación 20, 2023marcador acrílico, bolígrafo de tinta de archivo sobre papel reciclado48 x 48 pulgadasJOSIAH LEE LOPEZThis illustration is based upon characters and symbols depicted in the Aztec calendar. Its narrative is the formation of the calendar in its early stages of creation. It is before the universe was a whole and complete. In discombobulation the symbols and characters strive to find their way in the universe. Tonatiuh is in the center of the drawing portrayed as a child surrounded by 20 days and the four eras of cataclysmic destruction.Esta ilustración se basa en personajes y símbolos representados en el calendario azteca.Su narrativa es la formación del calendario en sus primeras etapas de creación. Es antes de que el universo fuera un todo y estuviera completo. En confusión, los símbolos y personajes se esfuerzan por encontrar su camino en el universo. Tonatiuh está en el centro del dibujo retratado como un niño rodeado por 20 días y las cuatro eras de destrucción cataclísmica.

22Malinche on the Rocks, 2022mixed media & acrylic32 x 48 inchesMalinche en las piedras, 2022técnica mixta y acrílico32 x 48 pulgadasARLETTE LUCEROMarina or Malinzin was a Nahua Mexican woman who was enslaved as a child and given to the Spaniards in 1519 by the natives of Tabasco. Conquistador Hernán Cortés chose her as a consort, and she later gave birth to his first son, Martín who was one of the first Mestizos (people of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry). Marina is more popularly known as La Malinche because she acted as an interpreter, advisor and intermediary for the Spaniards. She was known as a traitor who contributed to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. My painting “Malinche on the Rocks” puts her in a new light. Not as a victim of slavery or sexual abuse from an obviously narcissistic conquistador. Nor as a treacherous plotter and destroyer of the mighty Aztec Empire. Instead, I depict La Malinche as the Mother of the Mestizo race. The mixed race of a future people who would populate the Americas. I painted her as a Goddess Mother who was the in between of both cultures. She stands strong on solid rocks in the middle and brings both the Spanish and Indigenous together as a new people of two blended cultures. The new culture of the Mestizo has a long and very interesting history as these people continue to mix and blend with other races.Marina o Malinzin fue una mujer mexicana nahua que fue esclavizada cuando era niña y entregada a los españoles en 1519 por los nativos de Tabasco. El conquistador Hernán Cortés la eligió como consorte y más tarde ella dio a luz a su primer hijo, Martín, quien fue uno de los primeros mestizos (personas de ascendencia mixta europea e indígena americana). Marina es más conocida popularmente como La Malinche porque actuó como intérprete, asesora e intermediaria para los españoles. Era conocida como una traidora que contribuyó a la conquista española del Imperio Azteca.Mi cuadro “Malinche en las piedras” la presenta bajo una nueva luz. No como una víctima de esclavitud o abuso sexual por parte de un conquistador obviamente narcisista. Ni como una conspiradora traidora y destructora del poderoso Imperio Azteca. En cambio, represento a La Malinche como la Madre de la raza mestiza. La raza mixta de un pueblo futuro que poblaría las Américas. La pinté como una Diosa Madre que era el punto intermedio entre ambas culturas. Ella se mantiene firme sobre piedras sólidas en el medio y reúne a los españoles y a los indígenas como un nuevo pueblo de dos culturas mezcladas. La nueva cultura de los mestizos tiene una historia larga y muy interesante, ya que este pueblo continúa mezclándose y fusionándose con otras razas.

23Nepantla, 2024acrylic30 x 40 inchesNepantla, 2024acrílico30 x 40 pulgadasEMANUEL MARTINEZNepantla“In the beginning, a sperm enters an egg to begin the creation of cells and life. The Mestizo, a tri-faced head, depicts my mixed ancestry and how I perceive myself between two histories. The turtle represents the earth and the sustainer of life. The feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl, is Mesoamerica’s Creator deity. Two hands hold spheres to symbolize balance.”Nepantla“En el principio, un espermatozoide entra en un óvulo para iniciar la creación de células y vida. El mestizo, una cabeza de tres caras, representa mi ascendencia mixta y cómo me percibo a mí mismo entre dos historias. La tortuga representa la tierra y el sustentador de la vida. La serpiente emplumada, Quetzalcóatl, es la deidad creadora de Mesoamérica. Dos manos sostienen esferas para simbolizar el equilibrio”.

24Danza de La Nepantla, 2024acrylic and collage on panel46 x 36 inchesDanza de La Nepantla, 2024acrílico y collage sobre tabla46 x 36 pulgadasSYLVIA MONTERO“Danza de La Nepantla” is my expressionistic, creation of what Nepantla means to me.As a former dancer, ‘space’ has been a constant thought in my art forms as well as my spiritual foundation.Nepantla to me is the cosmic birth of traveling through space and time.I am in a constant Nepantla state of mind as I live in a complex society which is determined to define me in terms which do not apply to me yet attempt to restrict my existence. This piece is a reflection of myself existing in the western world and in my indigenous world. In my piece, the body is breaking through the universal creation of time, space and human form. She is free from all obstacles breaking space with her energy and her spirit. She is embracing the waters of infinite time as she dances to the fossil record.“Danza de La Nepantla” es una creación expresionista mía de lo que Nepantla significa para mí.Como ex bailarina, el “espacio” ha sido un pensamiento constante en mis formas de arte, así como en mi base espiritual.Para mí, Nepantla es el nacimiento cósmico de viajar a través del espacio y el tiempo.Estoy en un estado mental Nepantla constante, ya que vivo en una sociedad compleja que está decidida a definirme en términos que no se aplican a mí, pero que intentan restringir mi existencia. Esta pieza es un reflejo de mi existencia en el mundo occidental y en mi mundo indígena. En mi pieza, el cuerpo está abriéndose paso a través de la creación universal del tiempo, el espacio y la forma humana. Ella está libre de todos los obstáculos rompiendo el espacio con su energía y su espíritu. Ella está abrazando las aguas del tiempo infinito mientras baila al son del registro fósil.

25Somos Latinos, 2022 acrylic on wood panel32 x 72 x 1 inchSomos Latinos, 2022acrílico sobre panel de madera32 x 72 x 1 pulgadaDAVID OCELOTL GARCIAColorado-based artist David Ocelotl Garcia (b. 1977, Denver, CO USA) is accomplished across several mediums including painting, sculpture, and murals. His work can be seen in national and international public art commissions, and both museum and private collections. Through self-meditation and creative exploration David has developed his own technique and philosophy on painting and sculpture coined “Abstract Imaginism.” David is most inspired by the presence and movement of atomic energy and its influence and connectivity with all living things. In addition, David’s passion is to explore the beauty, philosophy, and spirituality of his Native heritage.It is through art that David hopes to manifest beauty, inspiration, color and energy.David Ocelotl Garcia (nacido en 1977 en Denver, Colorado, EE. UU.), artista radicado en Colorado, trabaja en varios medios, como pintura, escultura y murales. Su trabajo se puede ver en encargos de arte público nacionales e internacionales, y en colecciones privadas y de museos. A través de la automeditación y la exploración creativa, David ha desarrollado su propia técnica y filosofía sobre la pintura y la escultura, denominada “imaginismo abstracto”. La mayor inspiración de David es la presencia y el movimiento de la energía atómica y su influencia y conexión con todos los seres vivos. Además, la pasión de David es explorar la belleza, la filosofía y la espiritualidad de su herencia nativa. Es a través del arte que David espera manifestar la belleza, la inspiración, el color y la energía.

26Hope lives in Bernardo, 2023acrylic on wood panel47 x 36 inchesLa esperanza vive en Bernardoacrílico sobre pannel de modera47 x 36 pulgadasCIPRIANO ORTEGA“Hope lives in Bernardo” is a part of my ongoing series “Beautiful Machismo.” In this body of work, I am showcasing Latino men that show me a side beauty that I believe should be seen more. There is an elegance to how Bernardo was posed naturally. I was deeply moved by his overall presence. I saw myself in his presence. I wanted to capture that moment to share his beauty with others and to remind myself that when life gets overwhelming there is always hope. For me hope is an in-between feeling. Hope is evasive, elusive and sometimes impossible to find. Bernardo is smiling and looking towards the future. For me that gives me hope.“La esperanza vive en Bernardo” es parte de mi serie en curso “Machismo Hermoso”. En este conjunto de trabajos, muestro hombres latinos que me muestran una belleza lateral que creo que debería verse más. Hay una elegancia en la forma natural en que posó Bernardo. Me conmovió profundamente su presencia en general. Me vi a mí mismo en su presencia. Quería capturar ese momento para compartir su belleza con los demás y recordarme que cuando la vida se vuelve abrumadora, siempre hay esperanza. Para mí, la esperanza es un sentimiento intermedio. La esperanza es evasiva, elusiva y, a veces, imposible de encontrar. Bernardo está sonriendo y mirando hacia el futuro. Para mí, eso me da esperanza.

27Nepantla, 2024 woodcut 35 x 49 inchesNepantla, 2024xilografía35 x 49 pulgadasTONY ORTEGAThe precolonial background designs reveal a timeline from the past to the present. The juxtaposing of the Cholo, a hip, street smart, warrior on the left, and the Adelita, a Mexican female revolutionary on the right, reveal the intersection of time periods in history that include the pre-Columbian, colonial, Mexican revolution, and present. The Cholo has his sleeves rolled up and is ready to go to work; the Adelita has a rifle at her side. They are both ready to battle for cultural preservation, historical acknowledgment, and social justice. The woodcut becomes part of the continued evolution of self-determination for those who have been marginalized.“Nepantla is a Nahuatl (Aztec language) term which describes being in the middle or the space in the middle.”1 The central figures exist in Nepantla. They physically, emotionally, and spiritually live between the clash of two cultures, one Mexican and one American. They must cross a border — not the actual Mexican and U.S. border but the subsequent cultural values that exists between these two countries. Here in the Aztlán (American Southwest), the northern outpost of Latin America, lays their journey from south to north. They must deal with a dominant culture whose history is from east to west. In their passage, they must think from Spanish to English, community to capitalism, family to individuality, and back again.The woodcut “Nepantla” metaphorically focuses on Chicanos/Mexican Americans who feel alienated from the dominant American culture and, as a result, search for their own personal individual meaning. My print asks the viewer, “Who am I in this cultural mix that refuses to recognize me as an individual? Where do I fit? How do I define myself?” And the answer is “somewhere in between.” And that is Nepantla.1 “About Us,” Nepantla, https://www.nepantlaculturalarts.com/about (Accessed Aug 17, 2024).Los diseños de fondo precoloniales revelan una línea de tiempo desde el pasado hasta el presente. La yuxtaposición del Cholo, un guerrero moderno e inteligente de la calle a la izquierda, y la Adelita, una revolucionaria mexicana a la derecha, revela la intersección de períodos de tiempo en la historia que incluyen la época precolombina, la colonial, la revolución mexicana y el presente. El Cholo tiene las mangas arremangadas y está listo para ir a trabajar; la Adelita tiene un rifle a su lado. Ambos están listos para luchar por la preservación cultural, el reconocimiento histórico y la justicia social. La xilografía se convierte en parte de la evolución continua de la autodeterminación de aquellos que han sido marginados.“Nepantla es un término náhuatl (idioma azteca) que describe estar en el medio o el espacio en el medio.”1 Las figuras centrales existen en Nepantla. Viven física, emocional y espiritualmente entre el choque de dos culturas, una mexicana y una estadounidense. Deben cruzar una frontera, no la frontera entre México y Estados Unidos, sino los valores culturales que existen entre estos dos países. Aquí, en Aztlán (suroeste de Estados Unidos), el puesto avanzado del norte de América Latina, se encuentra su viaje de sur a norte. Deben lidiar con una cultura dominante cuya historia va de este a oeste. En su travesía, deben pensar del español al inglés, de la comunidad al capitalismo, de la familia a la individualidad, y viceversa.El grabado en madera “Nepantla” se centra metafóricamente en los chicanos/mexicoamericanos que se sienten alienados de la cultura estadounidense dominante y, como resultado, buscan su propio significado individual. Mi grabado le pregunta al espectador: “¿Quién soy yo en esta mezcla cultural que se niega a reconocerme como individuo? ¿Dónde encajo? ¿Cómo me defino?” Y la respuesta es “en algún lugar intermedio”. Y eso es Nepantla.1 “Sobre nosotros”, Nepantla, https://www.nepantlaculturalarts.com/about (consultado el 17 de agosto de 2024).

28Nepantla Study II: Rec, 2024 watercolor and ink19 x 16 ¼ inchesEstudio de Nepantla II: Recreación, 2024acuarela y tinta19 x 16 ¼ pulgadasVANESSA PORRASI spent a lot of time looking at the tiles at the bottom of the pool as I practiced steady breathing in an attempt not to drown. Learning a new skill as an adult is never easy, much less when it feels like you’re going against any rational sense of self-preservation. Whenever I would reach the middle of the pool inching towards the deep end, the vastness of the darkening water would feel too overwhelming and once again, I would have to steady my breath as my fear grew louder. Over time, I came to realize that fear grew in places that were unknown, undiscovered, and untamed. My work is a series of studies that uses the theme of Nepantla, meaning the space in between. It is an exploration of the objects that help steady our breath when we are caught in the whirlwind of the unknown and the fear that comes with it before we can reach the other side. It’s a meditative practice of Drishti, the Sanskrit word for point of focus, and turning ordinary, imperfect objects into anchors and glimmers of hope.Yo pasé mucho tiempo mirando las baldosas del fondo de la piscina mientras practicaba la respiración constante en un intento de no ahogarme. Aprender una nueva habilidad como adulto nunca es fácil, mucho menos cuando sientes que vas en contra de cualquier sentido racional de autoconservación. Cada vez que llegaba al medio de la piscina y me acercaba lentamente al extremo más profundo, la inmensidad del agua que se oscurecía me resultaba demasiado abrumadora y, una vez más, tenía que controlar mi respiración a medida que mi miedo se hacía más fuerte. Con el tiempo, me di cuenta de que el miedo crecía en lugares desconocidos, no descubiertos e indómitos.Mi trabajo es una serie de estudios que utiliza el tema de Nepantla, es decir, el espacio intermedio. Es una exploración de los objetos que ayudan a estabilizar nuestra respiración cuando estamos atrapados en el torbellino de lo desconocido y el miedo que lo acompaña antes de poder llegar al otro lado. Es una práctica meditativa de Drishti, la palabra sánscrita que significa punto de enfoque, y que convierte objetos ordinarios e imperfectos en anclas y destellos de esperanza.

29Santuario 2, 2024 mixed media 8½ x 11 inchesSantuario 2, 2024técnica mixta8½ x 11 pulgadasDR. GEORGE RIVERADr. George Rivera’s artwork focuses on the Nepantla between life and death in one’s lifetime. All human beings (past, present and future) must answer the question: WHY ARE WE HERE? Before death engulfs life, one must contemplate how we have lived our lives.La obra de arte del Dr. George Rivera se centra en la Nepantla entre la vida y la muerte en la vida de una persona. Todos los seres humanos (pasados, presentes y futuros) deben responder a la pregunta: ¿POR QUÉ ESTAMOS AQUÍ? Antes de que la muerte se trague la vida, uno debe contemplar cómo hemos vivido nuestras vidas.

30San Ysidro Labrador, 2024 wood, watercolor24 x 11 x 1 inchSan Ysidro Labrador, 2024 madera, acuarela 24 x 11 x 1 pulgadaCATHERINE ROBLES SHAWI am a self-taught artist painting and wood carving Spanish Colonial Art since 1991. I decided on this form of art after visiting the small towns of Southern Colorado and New Mexico in 1991, being 5th generation in this art.In 1995 I did my first shows in Santa Fe and Colorado. I have specialized in making Altar Screens, Retablos and Bultos, preserving this art from 400 years ago. I have won over 40 awards and my work is in 8 Museum collections, private homes, chapels and galleries. I am in 14 books on the subject of Spanish Colonial Art.Soy una artista autodidacta que pinta y talla madera, y que ha trabajado en el arte colonial español desde 1991. Me decidí por esta forma de arte cuando visité los pequeños pueblos del sur de Colorado y Nuevo México en 1991, siendo la quinta generación en este arte.En 1995 hice mis primeras exposiciones en Santa Fe y Colorado. Me he especializado en hacer biombos, retablos y bultos, preservando este arte de hace 400 años. Yo he ganado más de 40 premios y mi trabajo se encuentra en 8 colecciones de museos, casas particulares, capillas y galerías. Estoy en 14 libros sobre el tema del arte colonial español.