Return to flip book view

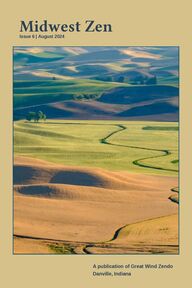

Midwest ZenIssue 6 | August 2024A publication of Great Wind ZendoDanville, Indiana Message

– ii –Cover: detail from photograph of the Palouse by Jay Tuttle.

– i –Midwest ZenIssue 6 | August 2024

– ii –ESSAYS POETRY 길거리 토스트 QUESTIONS ON PRACTICE CALLIGRAPHY PHOTOGRAPHS BIOGRAPHIESCONTENTS

– 1 –Zuiko Redding

Daishin McCabe– 2 –Flowers Fall, Fruit EmergesIn pre-modern times, it was a given that fruit would be local and eaten in season. It would be unheard of to have blueberries in the winter. These days, however, eating food that is locally grown and in season is truly precious and rare, at least where I live. I had the recent good fortune to taste mouthwatering strawberries from my mother-in-law's backyard in June, after having eaten non-local, out-of-season strawberries through the late winter and early spring. While it’s amazing what technology and modern transportation has done for us, there was no comparison between in-season and out-of-season strawberries. Though my mother-in-law’s berries were smaller, they were packed with sweetness, unlike the others that tended to be dry and borderline sour.In my own garden, the grapevines are bursting with bundles of tiny green bulbs that will eventually become grapes later this summer. My aronia berries (native to the Midwest) are abundant too, and though these black-colored berries are astringent, they are chock-full of antioxidants and give a beautiful deep purple hue when blended with other fruits in a smoothie.A sangha member gifted me two dwarf g trees, and I eagerly anticipate their fruit. They remind me of my recently deceased father. Dad planted what became a gigantic g tree in his own yard that continues to give. My pear and plum trees have been struggling to produce owers the past several years. I’m grappling to understand why. No owers, no fruit, unfortunately.Flowers and fruit also take on symbolic meaning in spiritual writings, such as Zen Master Dogen’s Genjo Koan, where he writes, “Flowers fall even though we love them. Weeds ourish even though we dislike them.” “Flowers” may represent spiritual experiences that eventually fade away with time, yet we chase after the past, hoping to preserve the good times. My teacher, Dai-En Roshi, often warned us not to chase after previous experiences, saying, “Do you have the experience, or does the experience have you?” This is important to keep in mind as we enter a world where the traditional four seasons continue to lose their integrity. With the climate becoming unpredictable, we may nd ourselves yearning for the past when nature was in greater balance. But here we are.Creating an “Ecological Civilization,[1]” one where human beings allow the more-than-human beings to exist and even ourish, is now imperative. We Buddhists vow to accomplish the impossible because it gives us the strength we need in difcult times. We don’t know what the future holds, and there’s no going back to the past. Now, we can’t afford to forget the four great vows. These great vows provide the kind of vision that humanity needs to rise to the challenges that face us for generations to come.This saying, “Flowers fall, fruit emerges,” reminds me that enlightenment is not the endpoint of my practice, but the beginning.

– 3 –Daishin McCabe

Daishin McCabe– 4 –Seeing the universe as Self is enlightenment, and it is also our practice. Moreover, enlightenment is not the purview of a few select people; it’s up to ordinary people to attain, and it’s a means to usher in an ecologically sensitive era that sees humans as one among many species, with all species having an integral part of life that goes beyond human use.We begin practice when we are gripped by the self that sees itself. When we look out at the hackberry trees, the chipmunks, the clouds, the sun, and the fox and see them as our ancestors, as what has given birth to us humans,[2] we are gripped by our self. The squirrel that sees you is nothing less than your evolutionary ancestor viewing its descendants. From the moment of Enlightenment onward, it becomes our responsibility to practice that insight in everyday life. Just as an infant lacks the ability to form coherent words to communicate with her parents and lacks the intellectual capacity to articulate their relationship with adults, we humans are similarly like infants in relation to the Earth and the innite array of species. Our groping to understand ourselves in relation to the universe, too, manifests as the wondrous Dharma.Our daily practice, both in the meditation hall and in the world, can be seen as the fruit of an initial Enlightenment experience. However, this fruit must always remember its ower. We must recall that humans evolved through processes spanning billions of years—no ower, no fruit. The ower gives birth to the fruit, which is an ongoing awakening fostered by skillful, everyday, moment-to-moment practice.This everyday, ordinary practice-enlightenment (fruit-ower) has a rippling effect around the planet where we humans activate our role among all the other species, as that aspect of the universe that has the ability to reect on itself, or, as Dogen Zenji puts it in Genjo Koan, “That you go forth and experience myriads of things is delusion. That myriad things come forth and experience themselves is Awakening.”P[1] For more on Ecological Civilization, see the embedded link. Dr. Mary Evelyn Tucker, professor emeritus at Yale Divinity school articulates what is already happening in various countries in Asia.[2] It may sound strange to say that foxes and other creatures gave birth to humans. I’m speaking from a deep-time perspective. Modern humans evolved more recently on our planet—some two to three hundred thousand years ago. It’s thanks to the creatures that have preceded us that we exist. From this perspective, they “gave birth” to us.Mark J. Mitchell– 4 –

Daishin McCabe– 5 –– 5 –Mark J. MitchellNo Eyebut seeingfallen blossomsairborne andyoung sunrunning itstrue courseacross skythrough starstoo dimfor daylight.Seeing butnothing to see with.

Mark J. Mitchell– 6 –e Parable of the MalaTuft on the Bodhi beadbrushes your palmbrushes your palmbrushes your palmwith each breathit clings a littlethen slips offemptiness greets youyou breathe a circle untiltuft on the Bodhi beatbrushes your palm– 6 –

Mark J. Mitchell– 7 –– 7 –Géry Parent, Hexagonaria percarinata, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Mark J. Mitchell– 8 –e Return of Polly Cannon (her day)Polly Cannon sits empty as a stone. She thinks she may exist right here, in this one place. She’s alone wearing her rst face. Seeing where no thoughts will t. She’s still and happy. She sits. Polly Cannon smiles like an ancestor while scrubbing kitchen tiles until light blinds her clear eyes. She seeks more of nothing, No true lies. No bells. She empties her guile and dirty water. She smiles.Polly Cannon cooks— always at midday, till her meal’s a perfect book of koans and wide gathas— a small gate into pure laughter. She takes her bowl off its hook and eats everything she cooks.

– 9 –Mark J. Mitchell Polly Cannon smiles. She’s not made of words. She lies down, watching night sky— embracing, not seeking, sleep. City birds sing low. Sky goes deep black. Eyes closed like a child, Polly Cannon rests. Stars smile.Polly Cannon walks. The pavement’s her home. She sees those who don’t know, talks nonsense. They watch her new face. It’s unknown by name. She never mistakes. Time for place and doesn’t halt her travel. Polly just walks.PThe stanzas are in a form called Sishin Ze Ge (46 syllable songs). It was a popular folk form in San Francisco's Chinatown in the 19th century.

Mark J. Mitchell– 10 –SittingTouch of white beadstames the ngers.Tamed ngers call the breath.Breath beatssoftly, calming time. Calm time, tame ngers.Soft breath. No mind.

Mark J. Mitchell– 11 –the Palouse

Tonen O'Connor– 12 –Dharma Gates are BoundlessA few years ago, the cover of an issue of Buddhadharma magazine featured an announcement for an article on “How to Adapt Your Practice in Old Age.” “Hmmph!” I thought, “I’m not adapting my practice in old age. Old age is the practice.”There was truth in this thought. We so often separate our daily lives from our practice, thinking that it is conducted in a particular way and a particular posture. The person quoted bemoans the fact that prostrations are no longer possible, without understanding that this is a gate to a personal experience of the Buddha’s teaching on impermanence. We forget that the Buddha taught not that we should simply observe emptiness of xed self in the things around us, but that we should experience it deeply in our own lives.Each instant of our daily life is practice, and each moment offers a dharma gate into the truth. The third of the Four Bodhisattva vows says: “Dharma gates are boundless, I vow to enter them.” To enter them we must recognize them as they rise before us, offering boundless opportunities to experience “things as they are.” If I am not mindful, the vegetables roasting in the oven will burn. I turn the key in the ignition of my car, opening a dharma gate to the interconnectedness of all things as my ngers, the key and the engine work together to realize the comforting purr that says I can back out of my driveway.Even more important than the lessons offered by my day are the demands that day makes for me to practice the deep principles of respect, helpfulness, awareness and care for others that are the backbone of my Buddhist faith. Here are selections from the Vimalakirti Sutra that clarify the nature of a practice that offers us passage through dharma gates. In it, the young bodhisattva Shining Adornment describes an encounter with the Layman Vimalakirti.Vimalakirti was then entering the city and I accordingly bowed to him and said,“Layman, where are you coming from?”He replied, “I am coming from the place of practice.”“The place of practice—where is that?” I asked.He replied, “An upright mind is the place of practice for it is without sham or falsehood. The resolve to act is the place of practice for it can judge matters properly. A deeply searching mind is the place of practice for it multiplies benets … Almsgiving is the place of practice for it hopes for no reward. Observance of the precepts is the place of practice for it brings fulllment of vows. Forbearance is the place of practice because it enables one to view all beings with a mind free of obstruction … Meditation is the place of practice for it

Tonen O'Connor– 13 –makes the mind tame and gentle. Wisdom is the place of practice because it sees all things as they are.”In each instant of our daily lives we arrive at a dharma gate. Let's try to practice so that these dharma gates open to the truth of things as they are.PQuote from Vimalakirti Sutra from a translation by Burton Watson.Photo by MonikaRiimaitee, Vabi Sabi,Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Dave Malone– 14 –Forsythia Overnight If you weren’t paying attention, you are now. There is goldhanging like Christmas tree starsin bushes on your front lawn.There is gold lining the south side of the savings and loanand blanketing the dark windows.There is gold short-lived and forgottenin that old poem by Frost. There is gold behind the high school football eld.Nature’s rst green restslike a Buddhakeeping a watchful eyeat lunch break when kidshuff and puff in noontime sun,their legschurning circleson the ancient cinder track.

Dave Malone– 15 –e Middle Way Today, I want to avoid all the deep things.Like poems, most of all. But also cooking potsand Olympic pools and my parents’ sad eyes.Today, I want to avoid all the shallow things. Like chitchat, most of all. But also skilletsand puddles and my parents’ thin love. Today, I want to sit in the middle of all things. Like birdsong, most of all. But also a plate of pastaand drizzle and forgiveness.

Ed Mushin Russell– 16 –Our PracticeLet’s take a look at this business we call our practice. We can call it Zen practice, Buddhist practice, mindfulness practice or whatever. Our labels for things are simply conveniences we use to communicate but, it's helpful to be clear about what our words mean. Let’s see if we can clarify what we mean by our practice. What it is and how we do it. When it comes to this practice, we are all, and always, beginners. When the elderly Buddha was asked to reect on his life, he replied, "I'm always at the beginning." And yet, we are all experts. Fully qualied to be who and what we are. In each moment we begin our journey and, in each moment, we have arrived at our destination and this is it.When used as noun, the word practice is dened as "the actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method, as opposed to theories relating to it." We need to be aware of our ideas and beliefs about our practice but they have limited value. The application of our practice is more relevant and I'll talk about that shortly. But, the "as opposed to theories relating to it" part is something we should be aware of. Our practice has nothing to do with theories except as an opportunity to notice our ideas and beliefs. It's organic, immediate and experiential. It's the actual application and experience of our life, as it is, right here now. When and where else can our practice take place?When used as a verb, the word practice is dened as "to perform an activity or exercise a skill repeatedly or regularly in order to improve or maintain one's prociency." The rst half of this denition works for us but the second half, not so much. Our practice effort is all about being present, noticing our reactive habits and sitting zazen, repeatedly and regularly, however much we would rather not. We all have the skills necessary to do this. The second half, however, sounds like we need to have a goal in mind, to improve or maintain our prociency. Is anyone procient at this practice? I doubt it. What would that even mean? What we are procient at is our life. We all have the ability and skills we need to be who and what we are. The activity and experience of our life is our practice. No need to look any further.Maizumi Roshi once said that we are all perfect, just as we are, and we could use some improvement. Dogen's question was, if we are inherently Buddhas, what's the use of practice? What can we hope to gain by our efforts? A fair question and the answer is nothing. It's simple, really. We don't need to change who and what we are. Our practice is to realize and appreciate the truth of who and what we are. It isn't some mysterious or hidden secret. It's right here all the time. Our true nature is always staring us in the face. Everyone and everything we encounter is reecting this truth. That's the beauty of our practice. In Ode to a Grecian Urn, Keats says "Beauty is truth, truth beauty. That is all you know on Earth, and all you need to know."So far, I've been talking about what our practice fundamentally is. Experiencing and being just this moment. It's quite simple and yet, no easy task. Now, let's focus on how we do it or, you might say, the nuts

Ed Mushin Russell– 17 –and bolts of our practice. The fundamental element of our practice is, of course, our zazen, our sitting. Teachers, talks and texts support our practice but, our sitting is key. Whether we are just being present, counting breaths, labeling thought or working on a koan, it's basically the same. We are ne tuning our ability to be this moment experiencing, even when it seems boring or useless. Sitting with others is also important since there is great support in the shared effort and in knowing that you are not in this alone. And nothing supports our practice effort more than sesshin.So, does this meditation thing work? If we sit still and stare at the wall long enough, will the clouds of delusion suddenly part and the pure light of ultimate wisdom shine forth to illuminate every ber of our being? Perhaps, but I wouldn't hold my breath. What's much more likely is that, gradually, we will begin to see the wall just as it is without trying to paint over it with our expectations and aversions. We will begin to appreciate how wondrous and ungraspable this life is and always has been. We don't need to discover Buddha Nature. It's right here all the time. We need only cease looking for something else and give ourselves completely to what is. Turns out, there are no clouds to obscure our vision except those we create and the pure light of wisdom is simply the candle on the altar. It illuminates everyone and everything freely, without bias or distinction.Where our practice mostly takes place is out there, so to speak, in our life. Eventually, the bell is struck and sitting is done and now what? Truly, our practice is our life and, our life is our practice. We might be disappointed if we are looking for some special activity or experience that will x our life. As important as our sitting is, we eventually have to get up and go home, or to work, or to the store, or wherever. And, that's where we bump up against our attachments and where our reactive habits are manifest. It's the ground where our practice efforts are relevant and necessary, and the effort is to be present and to appreciate and embrace this life as it is. Only then can we respond with skill and compassion to whatever the universe offers us. Our zazen helps prepare us for this effort, but our everyday life is where the true effort is made.

Fūmyō Michaela Robošová– 18 –Seven Poemsrst butteryutters its wingsbird's chirpa snail munchingon the salad seedlingenjoy the meal!a spider in the snail shell—when my time comes may these bonestoo become someone’s new homea spring city walkday after day I stumblemy way to enlightenment

Fūmyō Michaela Robošová– 19 –a speck of dustsitting on a chairZoomingsoft grassesa baby hare restsin its hiding placewide openrosehip owersBuddha's eyes

Neil Schmitzer-TorbertA awed approaAt one level, I appreciate that meditation practice does not have a nite goal — there is no nish line out there in the distance. Our zazen, if it is full of life, can likely always grow and deepen. Even so, I continue to be surprised, and humbled, by what comes up for me on and off the cushion. For some time, what has been bubbling up to the surface is a greater awareness of friction, or resistance, in my practice. It can often show up as tension in the body or feelings of fatigue, which seem to be related to my own striving, when I nd myself reaching to have the “right” experiences or to practice in the “right” way. This all came into sharper focus for me about a year ago. During a sewing retreat at the Sanshin Zen Community, I was able to spend a few days immersed in the temple’s daily practice. Like more intensive sesshins, I saw that this was an opportunity to deepen my practice, and I was grateful to be able to participate with the community. But I also approached that time in the same way I approached practice in general, as something serious, and which needed a serious effort. I didn’t see how that attitude affected my experience, and how I was getting in my own way.During the week, I took informal meals with the priests who were in residence at the time. In one discussion about practice that came up over breakfast or dinner, I remember someone quoting from the Fukanzazengi, where Dogen pointed to zazen as “simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss.”[1] In the moment, I was struck, and I think commented, half-joking, “Wait, this is supposed to be blissful?”Now, you might nd that reaction humorous (or odd), but when I found myself caught off guard — and became aware of my own surprise — it was a true gift. I often forget how some parts of my life become so ingrained that they are invisible, except perhaps when I bump into them unexpectedly. In that moment, it stopped me cold when I slammed into my own assumptions about practice. And, this helped me to see some of the ways in which I had been making my zazen practice, and my entire life, harder than it needed to be.What I had recalled from the Fukanzazengi were the recommendations for meditation: how we should sit, and how we should approach zazen. Probably, this stuck with me because of my own disposition. My rst bias is often to reach for an intellectual understanding, and I tried to grasp what it is that we are aiming ourselves towards in zazen. While this conceptual understanding can be helpful, and will likely always be important to me, I can be slow to see the ways in which it becomes a hindrance. In this case, my ideas of what practice should be, and how it should be, became an obstacle. I fell into a habit of approaching practice as something special — something that should feel like a special kind of effort. It was so helpful to have a reminder that practice might not need to feel like strenuous, or like a chore. – 20 –

Neil Schmitzer-TorbertEven before this conversation, other experiences were drawing my attention to my relationship with practice. A few months earlier, our family had been going through a difcult time. In the midst of challenges, I did my best to keep up a regular meditation schedule and to carry my practice into the whole of my life. I would have said that this was going reasonably well, until I started to notice occasions when my limbs felt weak. Or my hands and ngers would almost seem to feel numb. This was concerning, but thankfully it also captured my attention, and I became curious to nd the roots of these experiences. Some part of it came from stress, that seems very clear to me. But, I do think my approach to practice contributed as well. Looking back, it was very difcult for me to be present with the physical and emotional feelings of distress that were coming up at the time. And also, part of me believed that I should not feel this way, if I was practicing “correctly.” Without intending to do so, I was pushing away from those sensations, trying to create some distance. I would describe it as a kind of leaning back, pulling away from my actual physical experience to avoid these sensations. As I was spending some time exploring my posture of leaning back from my body, I also became aware of an underlying current of tension in the body. It would come during zazen and in my daily life, and seemed to be related to trying to keep control of my thoughts and how I was feeling. Rather than leaning back, this felt like a clamping down, trying to control my experiences. As I sat with my awareness of these experiences of numbness and tension, a line came to my mind from Scott McCloud’s graphic novel, The Sculptor: “There’s a aw in my approach…or my methods, or my philosophy…Something basic, fundamental” (p. 297). In the book, the main character is a frustrated artist who has made a costly trade for a magical ability to sculpt any material with just his bare hands. Freed from physical limitations, he gleefully throws himself into his work. But, even with his newfound power, he is still stuck, unable to create a great work of art. He had believed that he was limited by his materials and his tools, but it turned out that he did not know what he really wanted to say with his work. This idea of misunderstanding our obstacles resonated with me deeply. “There’s a aw in my approach.” I held on to this intuition, lightly, as I continued my practice and looked more closely at the aws in my approach. Bit by bit, I became more aware of how difcult it still can be for me to dedicate myself wholeheartedly to practice without giving up the idea that practice will lead somewhere, or feel special in some way. On a practical level, I worked with these challenges by giving more attention to how I was pulling back from my experiences in the body. I experimented with leaning forward, into all of my physical sensations, grounding myself more completely in the body. And I noticed a sense of friction, where I was clamping down on thinking or feelings that were troubling. I felt constricted or inhibited in these moments, like I was – 21 –

Neil Schmitzer-Torberttrying to drive a car while riding the brakes. So, I tried to relax this habit, and let up on the brakes and let myself move forward more freely. Over time, those feelings of weakness or numbness subsided, as well as the feelings of tension or inhibition. Perhaps this was because I was able to work with my own tendencies more skillfully once I became aware of them. Or maybe they faded because challenging times in life come and go. Most likely, it was a bit of both — a blend of more skillful effort and time. Either way, it has been helpful for me to notice this tendency, even as it becomes ever more subtle, to make meditation practice into a heavy handed effort towards a goal. Sometimes it still shows up in a belief that practice should be (feel) a certain way. Sometimes it shows up as I wrestle with thoughts, or nd myself trying to suppress thinking. It can sneak up on me, imperceptibly, but at some point I’ll notice a sense of friction in my life. Something beyond normal tension, or the fatigue that can come with a long day’s work. I’ll notice it in the body, or in a sense of inhibition, that I’m holding myself back in some way. If I can, I’ll then try to relax, physically and mentally. To lean forward, to ease off of the brakes, settling back more easily into the experience of each moment.And while I cannot say that my experience in practice has become “repose and bliss,” I have found a greater sense of ease and contentment. At least when I am able to get out of my own way. P[1] From Norman Waddell and Abe Masao’s translation, included in The Art of Just Sitting.– 22 –– 22 –

Neil Schmitzer-Torbert– 23 –– 23 –Photo by AgainErick, De IJskelder - Park de Buitenplaats - Zestienhoven - Overschie - Rotterdam, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Robert Beveridge– 24 –길거리 토스트Rabbits in the cat food again, and catsat the chicken wire, after the cabbagein the garden. Some predator will beconfused at this spoor, rest assured.The vendor reaches for a carton of eggs,cracks them one by one into a shreddedmound. Carrots, scallions, condiments,bread, everything one needs for a goodbreakfast, human, feline, or leporine.PAuthor’s note: 길거리 토스트 translates to “Gilgeori Toast.” If you're unfamiliar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzZY7oDpdwU)

– 25 –Robert BeveridgeFrogpuddlelilypad ripplealgae shiftthrown stonelaughter

Robert Beveridge– 26 –CruentationYou’ve chopped wood long enough that you knowwhen the angle’s wrong, the swing is overpowered,the blade is headed for your thigh. Whether you havethe reexes to avoid it is another story indeed.Coins scatter on the ground in the midstof leaf debris, moss, the occasional snake.The pitter-patter you hear may be the startof an unseasonable summer storm. It may not.The cat stares out the window. He is stillsave a twitch in the left ear. He may standhunched, tail puffed, for hours; this ishis nature, just as yours lies on the ground.The wood must still, in the end, get to the house.You ignore the twinge, load the sled, start out.– 26 –

Robert Beveridge– 27 –– 27 –Photo by the blowup on Unsplash, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Zuiko ReddingKnowing It’s EnoughToday is one of those quiet autumn days when the birds and insects have stopped singing and the air is still. The temperature is pleasant and the leaves are still green. It’s enough.In Dōgen’s Eight Awarenesses of Great People, the Buddha says, “Monks, if you want to be free from suffering and anguish, you should contemplate knowing how much is enough. The place of satisfaction is one of richness, joy, peace, and calm.” [1]Knowing how much is enough is hard. We, like all human beings, have limitless desires, so we have to deal with getting clear about the nature of our wants. Since our modern society functions by encouraging us to have limitless desires, being clear can get pretty complicated. We can wake up to how this operates, though, and work with it. After all, having desires is useful. Not realizing that we can hurt others and ourselves by blindly following them isn’t. Knowing when we have enough is knowing when we have what we need. This is the Middle Way. We don’t turn the heat down so far that our teeth chatter, but we put on a sweater rather than turning it up to t-shirt temperatures. We also realize that our needs change. In previous years a basic telephone was enough, but today a cellphone is becoming a necessity.Knowing when we have enough is also being content with what we have. If we have the mind of contentment, we can be comfortable right where we are, not looking around for something better. If we don’t have this mind, we’re discontented and crabby even when we live in luxury. If we truly don’t have enough, we can be content with what we have until there’s a chance to get what we need. Or not. As we grow older, we realize that we’ll never again have the stamina and health we had in our twenties. Rather than wishing for what can’t be, let’s ask what we can do with what we have. Often the answer is surprising.Knowing how much is enough brings clarity and stability. Being comfortable with having what we need, we don’t get excited over all the bait dangled in front of us. You know that new cellphone with the pretty colors and fancier features, the new Fitbit that promises great health. We can assess our communications and tness needs and make a wise decision. And we can remember when we bought the latest new thing, then passed it on to a friend because we got bored with it or it wasn’t what we thought we needed.Seeing what we need, we also aren’t so excited by others’ opinions of us. We know who we are and what’s useful and not useful, and that’s enough. We don’t need to change our weight, way of thinking, or whatever to please others. We’re enough just as we are. Let’s receive what we’ve been given, knowing it’s enough in this moment. Rather than fussing over what we “should” have, we do good things with – 28 –

Zuiko Reddingwhat we do have, realizing that there’s something we can do with even the worst situation. We move forward with a quiet, stable center in the midst of a turbulent world, free of the discontent and paralysis of always wanting what we don’t have.P[1] For the entire essay, see Thomas Cleary (tr.), Shō bōgenzō : Zen Essays by Dō gen or Gudo Nishijima and Chodo Cross (trs.), Shō bō genzō , vol. 4.– 29 –

Diane Webster– 30 –InterruptedDesert duneinterruptedby a bloomingbush whitelike bleachedbones.DescentRed leaves coatthe green lichencovered stoneslying besidethe waterfallin whitedescent.

Diane Webster– 31 –Floats ReectLily pad oatsin the sky’s reectionas a jet streakslices under it.StitesBlackbirds stitcha ight seamunder the clothof gray cloudswhile rips of blueexpose the sky’s skin.

John Grey– 32 –Driving in the Rainrain that’s beenin the rearviewrain to comeout aheadrain on the roofand windshieldis happening nowJay Tuttle– 32 –

John Grey– 33 –Jay Tuttle– 33 –Photograph of the Palouse

Gail Sherestions on PracticeDo things for the things themselvesRegarding “If you do things not because of Buddha, or truth, or yourself, or others, but for the things themselves” what I have noticed is that when I clean to make things clean, I feel tired afterwards and usually want to rest, but sometimes, when I remember to clean to make things feel that they have been taken care of, I feel buoyant. So it must be true but how do I remember? Just cultivate the relationship between you and the thing. For example, I have quite a ourishing garden of plants in my studio and I know for a fact that I do not have a green thumb. But every day, at rst because I was so thrilled that they weren’t dying, I got into the habit of misting them. The better they did, the more enthusiastic I got about misting and now I make sure to mist every single leaf and nd myself talking to them encouragingly while I do this. Now that I feel that the plants have denitely responded to my care, I wouldn’t miss it for the world. So that’s my point. Develop a relationship with the things you clean. Ask them how they prefer to be cleaned? Does your wood table want this cleaner or that cleaner & polisher? Experiment. See if you can start a real conversation and know where in your body that this is taking place. You will enjoy yourself. It’s like making a new friend. You won’t forget.Even the air is not silentThis is a kind of big question but I hear the word “silence” a lot in these teachings and I wonder why silence or quiet is so important. Nature is not silent. Animals and birds and whales. Even the air is not silent. Could you explain?Katagiri Roshi speaks of this eloquently: “In terms of the universe of Buddha’s eye, silence is exactly as-it-is-ness, or what-is-just-is-of-itself. It is very quiet. Buddha’s teaching always mentions this. If we want to know who we are and touch the real, silent, deep nature of our life, we must be as we really are. That is why sitting (zazen) is very important for us.” In short, silence is important in that it allows us access to who we really are within a world that, one might say, makes a lot of noise. The more silence you nd in which to rest, the more you will crave it so that you can sink into yourself.Just surviving instead of livingI procrastinate too and then the next day, especially if it is beautiful and sunny, I forget all about my promises not to and continue to procrastinate. I’m just surviving instead of living but I also see that I do it again and again.It actually helps to recognize when you are slouching through your “precious human life” (as it is called in Buddhism). Some people just – 34 –

Gail Sherhaven’t looked at their life carefully. They will spend all day working hard at a job they don’t like and then spend the evening “winding down” from their hard work, in effect turning their entire life into this non-meaningful adventure. If you suggest a practice like zazen, they’re too busy or tired from being too busy. Often the excuse is money with the vague idea of “someday I’ll get a different job.” But those who have made a Lifetime Personal Vow know what they’re after and can organize their life around that. They are not as “at risk” for feeling their life was more or less meaningless when it ends. I think your dissatisfaction with where you are now means you are on the verge of changing. Awareness of just surviving instead of living is the prelude to change.Mind that is not busyMy question is on this idea of our always having a “mind that is not busy.” When I am “not busy” I am either surng the web, watching Netix, or checking my phone. I’m quite sure that this is not what the phrase is alluding to. What exactly does it mean? Is it certain that we all have it?Yes it is certain, not simply that you have it (so that you can lose it) but that you are it, because this mind that is not busy is the mind of “suchness.” Suchness, or ultimate you, ourishes in stillness and dead silence. In zazen sometimes there is a moment when one feels “locked in” sort of, as if one’s body is cinched in its single place and the mind is still in its single place even while thoughts arise and oat away like clouds naturally. It’s very uid yet at the same time stable. “Cinched” isn’t the best word but it does convey “rmly held” which is important. We all have access to this place which is arrived at through continuous practice. Try to touch this place in yourself and follow it. It’s there. It’s your basic natural self without adornment. Busyness is adornment, and all the examples you gave are forms of that.Right Effort is continuous practiceIs “Right Effort” always Continuous Practice?Yes. And “continuous” means “daily.” Including weekends. For example, in Zen monasteries it is customary to observe any day with a 4 or 9 in it as a “day off.” What is a “day off?” A day off is a day off work. The schedule is the same until after breakfast and picks up again at evening service which is just before dinner. After dinner there are two periods of zazen as always before bed. What is “off” is morning work period, noon service, afternoon work period and study hall. Lunch is a bag lunch. Zazen is never missed. That is our model. I know very well from my writing practice that missing a day makes it harder to get back the next day. It always seems to work that way even after years of practice. Whatever amount of time you have to sit zazen is ne. But it should be practiced every day. Not in spurts. This is a key point.The whole world is suffering– 35 –

Gail SherI have a lot of suffering and I see so many around me also suffering and now the whole world is suffering and I feel completely helpless. This idea that the sole reason for the existence of Buddhism is to relieve suffering, which I keep forgetting, how does this work?Don’t apologize for forgetting. Everyone does. It takes awhile fully to digest Buddhism. If you remember Siddhartha’s story, however, it’s easier. (Siddhartha was the Buddha before he had his awakening experience.) He was a prince and was protected from seeing the way commoners lived by his father the king. Accidentally on various unauthorized trips to the village, he saw sickness, old age and death. His shock aroused a great desire in him to solve this terrible problem. And he did this by leaving the palace and meditating and doing various austere practices for six years. From his deep insights through sitting he saw the interconnectedness of all beings and later developed a method (a skillful means) to teach others what he had realized: the four noble truths and the eightfold noble path (the fourth noble truth) e.g. All beings suffer (transmigrate)/There is a cause for this suffering (karma)/suffering can be stopped (it is possible)/here’s how to stop suffering (follow the eightfold path). Basically this path addresses our three main attachments: greed, anger, wrong views. I mean he tells us what to do!We are not helpless. The Eightfold Path is a menu for selessness and abandoning what’s called the three attachments that keep us locked into samsara. Following it closely your life becomes an offering. Lives that are offerings live on. That’s how it works. I hope you pin the eightfold path on your refrigerator and practice wholeheartedly. Thank you for asking. Your question helps everyone. When buddhas are truly buddhasWould you explain the lines “When buddhas are truly buddhas they do not need to perceive they are buddhas; however, even though they don't know, nonetheless they are enlightened buddhas and they continue actualizing Buddha.” I don’t get it.These words underline the theme “we don’t do zazen for our own purposes.” Actually, we don’t “do” zazen at all, zazen does zazen, though we do have to put our body in the right shape. But even though we don’t experience any benet or learning of any kind from our efforts and we start to feel that it’s a waste, even so there is enormous benet, not just for us personally but for the whole interconnected universe. Since that truth is an ultimate truth, we cannot know it with our minds. So that’s why Dogen says, “When buddhas are truly buddhas they do not need to perceive they are buddhas; however, even though they don’t know, nonetheless they are enlightened Buddhas and continue actualizing Buddha.” Since we can’t grasp ultimate truths, we take them partially on faith and partially on an instinct that tells us that this is true beyond our understanding. Unlike the popular view, faith plays a big part in Buddhism.– 36 –– 36 –

Gail Sher– 37 –– 37 –Dottie Mae, Girl on bike training wheels, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.

– 38 –BiographiesDaishin McCabe teaches at Zen Fields in Ames, Iowa, and at the Nebraska Zen Center in Omaha and is a chaplain at Mary Greeley Medical Center, also in Ames. Dave Malone holds a graduate degree from Indiana State where he �irst became interested in Zen. Recent work appears in Slant and Tipton Poetry Journal. He lives in the Missouri Ozarks. He can be found online at davemalone.net.Diane Webster's work has appeared in many literary magazines. She had micro-chaps published by Origami Poetry Press in 2022, 2023 and 2024. Her website is: www.dianewebster.com.Ed Mushin Russell is resident teacher at the Prairie Zen Center. He served as Elihu Genmyo Smith's attendant, completed koan study and became Genmyo's �irst Dharma heir in 2015.Fūmyō Michaela Robošová. My name is Fū myō and I am located in the Czech Republic. I practice life, Zen, poetry, and calligraphy, and that’s what I write about at Rustling Leaves (hps://rustling-leaves.blog/).Gail Sher received lay ordination from Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in 1970. She is a poet, writer, teacher and psychotherapist in the San Francisco Bay area. Jay Tuttle �inds the mix of art and science in photography very appealing. Making photographs that others enjoy is a great pleasure in his life. You can view his work at hps://www.jaytulephotography.com.John Grey is an Australian poet, US resident, recently published in New World Writing, North Dakota Quarterly and Lost Pilots. Latest books, Between Two Fires, Covert and Memory Outside The Head are available through Amazon. Mark J. Mitchell has published seven books. His most recent is Something to Be. He’s fond of baseball. He lives and sits in San Francisco.Neil Schmitzer-Torbert began his Zen practice in Minneapolis and now practices at Sanshin Zen Community. He teaches psychology at Wabash College and shares re�lections on practice and science on his blog at neuralbuddhist.com.Robert Beveridge (he/him) makes noise (xterminal.bandcamp.com) and writes poetry on unceded Mingo land (Akron, OH). Recent/upcoming appearances in Utriculi, Rat's Ass Review, and New English Review, among others.Tonen O'Connor is the resident priest emerita of the Milwaukee Zen Center. She currently leads two weekly dharma discussions on Zoom and oversees a monthly Zen Dialogue seminar which includes prison inmates as participants.Zuiko Redding was the founder of the Cedar Rapids Zen Center, serving as its teacher for 24 years until she passed away in April. She offered Buddhist teachings in local colleges and within the Iowa prison system, as well as serving on the Board of the Association of Soto Zen Buddhists, a national organization. Trained at Zuioji in Japan, Zuiko received dharma transmission from Tsugen Narasaki Roshi. She loved studying Japanese, gardening and her two lovely cats.

– 39 –

Sky Above Great Wind — Ryokan