Return to flip book view

Message

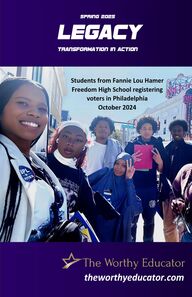

LEGACYTRANSFORMATION IN ACTION SPRING 2025 theworthyeducator.com Students from Fannie Lou HamerFreedom High School registering voters in Philadelphia October 2024

Legacy is the official journal of The Worthy Educator, elevating the good work being done by leaders in education who are working to change the narrative on the profession and actively plan for impact that transforms its future to serve the needs of a diverse, decentralized, global society that is inclusive, equitable and open to all people as next generations adapt, evolve and contribute by solving problems and creating solutions that meet the needs of a world we have yet to envision. Submissions are accepted on a rolling basis from educators who are implementing new and innovative approaches in the classroom and at the building and district levels. Information on specifications and instructions to submit can be found online at theworhtyeducator.com/journal. ©2025 The Worthy Educator, Inc. Founders: Shanté Knight Content Leadership Walter McKenzie Thought Leadership Gretchen Oltman Coaching Leadership theworthyeducator.com Contents Climbing New Summits: A Journey of Passion and Purpose Dan Reichard When Teachers Tell Their Stories, Change Happens Hannah Grieco What Was The Principal Thinking When She Said That? Carol Ann Tomlinson Reimagining and Innovating the Delivery of Education in Wyoming R.J. Kost Real World Learning: Civic Engagement for Students from the Bronx and Philadelphia Jeffrey Palladino The "Coach Approach" to Social-Emotional Growth: Why Special Education Students at a Continuation High School were able to Transition with Confidence to a Clear Post- High School Path Fran Kenton Shared Accountability in Education: Moving Beyond Blame Marlene Lawrence-Grant Authentic Learning Projects: Partnering Students and Community Members in Meaningful Learning Donna M. Neary The Continued Need for Servant Leaders in a Post-Pandemic Educational Setting: A Personal Perspective Joshua Medrano 6 10 14 24 31 38 45 53 57 Advocacy: The Critical Imperative: Advocacy for Public Education in a Time of Crisis Sheryl Abshire 49 2

P9T 3 6bA#yNominate yourself or a colleague and get celebratED for your success! get-celebrated.com/spotlighted P9TB328bA#y1Get yourself celebratED here! 3

A Call to Action If anyone tried to tell me last summer that this is where public education would be in the spring of 2025, I would have said they were crazy. Yet, here we are, and being a member on the tail end of the baby boomer generation, I cannot sit still nor stay quiet. We grew up in the turbulent sixties with the expectation that we make a difference. It is striking how much comes back to you sixty years later, like riding that proverbial bike; both instinct and muscle memory kick in. During those years we were taught western history, from Greek and Roman Times through the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the founding of our nation, the Civil War, and of course, the first and second World Wars. I was too young to understand the latter had just concluded fifteen years before my birth. It read like ancient history, and I made childlike assumptions that we had learned much from the past. My young mind couldn’t fathom people being seduced by propaganda and hate, nor how humanity allowed such atrocities to take place, so I naively assured myself our generation would never allow these things to happen again. Now in our golden years, we are facing disinformation and propaganda on a national scale, with an entire swath of people willingly buying in to the “afactual” (truth neutral?) okay lies and hate-mongering that is fueling movements against entire classes of people, our institutions and our rights. It’s no coincidence that public education, a cornerstone of our democratic society, is part of the targeting going on. What is inexplicable to me as that child of the sixties is how silent so many people are, sitting watching all this playing out in real time. Technologically we’re much more connected, but the disconnect to action is unjustifiable. Much like accounts from the past, entire groups are being singled out, scapegoated and victimized and the general public is laying low as if it isn’t happening, or as if it will just go away. The lies are so big they are overwhelming, and people shut down. I can make the plea that as citizens we all have a responsibility to each other, but this space is better used as a call to action specifically to educators. We have a special responsibility. We are the teachers, the role models, the truth tellers for each child that we welcome into our classrooms. Society depends on us to prepare them to become responsible citizens who contribute to the greater good, and they are watching. Let’s ratchet this down a notch. Consider this is one of those moments, like running into students while we’re grocery shopping. We’re not in our instructional setting, yet they look at us on a pedestal and want to know what we’re doing right down to peering into our cart. We can either pretend we don’t see them because we’re on our own time, or we can acknowledge them and make it a human moment, sharing our everyday selves right down to our choices of cheese and bread and beverages. Sure it’s easier to be left alone, but… In this moment in our personal and collective history as a people, each of us in education must share our humanity, speaking to what is best for children, to what is essential for public education, and to those American values we teach as content and now need to be demonstrated. There is no safety in silence. If we don’t stand and speak now, the damage being done will take generations to repair, assuming our descendants can ever recover everything we are losing. My more cynical boomer brethren tell me that you won’t respond until it affects you personally, and that by then it will be too late. I know so many of you in your thirties, forties and fifties and I don’t believe this is true. I’m asking you to stand up, speak out, and be a vocal majority standing up against the dismantling of our institutions, defending our rights and the rights of the most vulnerable among us. You don’t have to do anything more than what you have the wherewithal to do, but you must do what you can. Assess what’s possible and commit to action here. We’ve launched EDInfluencers at The Worthy Educator to support you with tools, strategies, and resources to advocate for our profession and for the students and stakeholders we serve. Participate in our virtual Town Halls, speak with colleagues and neighbors in your community, contact your elected officials and express your views as a voting citizen. Decisions are being made, and the time is now to make a difference in how it all plays out. Doing nothing surrenders your rights and our future. Do something. We are with you! Walter McKenzie 4

April offers two opportunities to Work with Dr. Chaunté Garrett! Monday, April 7th 7:00 p.m. e.t. Monday, April 28th 7:00 p.m. e.t. P 0T 336bA#ytheworthyeducator.com/get-unstuck P 0T 337bA#ytheworthyeducator.com/reset 5

Climbing New Summits: A Journey of Passion and Purpose Dan Reichard, M.Ed., Assistant Principal, Shrevewood Elementary School, Fairfax County Public Schools, Worthy Educator Leader, Fairfax, Virginia The Quiet Whispers They came in fits and starts - feelings of the need to turn back and start over. Google searches for new possibilities. Taking mental notes of how others connected passion and purpose. The courage to scale the heights of the new and unknown. A response to the many quiet whispers. The First Summit Thirteen years ago, in the final year of my undergraduate teacher preparation program, I was a student teacher in Pittsburgh Public Schools, eager to change the world. It was the beginning of the climb. Determined to secure a full-time teaching position, I set out on a long drive to Virginia for an interview - pursuing my lifelong dream with unwavering focus. With only a few pennies to my name, I took a leap of faith, inspired by a passionate principal - now my great friend and mentor, Kim Austin - who had called me on a Sunday morning, just a day after my college graduation, inviting me to visit the school she led. From the moment I stepped inside the school, I felt the energy - the strong culture, the deep sense of connection, the shared vision, and the unwavering sense of purpose. Shortly after, I accepted the offer. A lifelong dream, realized. My nine years teaching third and fifth grade at Kate Waller Barrett Elementary were filled with some of the greatest memories of my life to date. I was part of a team of mission-driven leaders and educators who constantly asked, "What if?" and made incredible things happen for students. I reached the summit of one of the most beautiful professional landscapes imaginable. My students became the Room 21 Rock Star Family, where they were part of something greater than themselves. They worked with effective effort to reach their goals, cheered on others with zest and kindness, and created a lasting classroom legacy. We transformed our space into immersive learning environments, traveled to the nation's capital to bring lessons to life, and established a social-emotional program that continues to foster belonging and connection today. In addition to education, one of my other great passions is hiking and exploring national and state parks. When you begin hiking a trail, you see the wooden marker indicating the name, length, and elevation at the trailhead. To me, the merge of passion and purpose mirrors the ascent of a mountain. My teaching journey was a challenging climb. There were nights I drove home wondering if I was making a difference - if the time and energy I poured into my students truly paid off. Teaching is hard work, and like hiking, there were moments I had to stop to catch my breath. But I never doubted that I was climbing closer and closer to my purpose. After nine years, I reached the summit. The breathtaking view made every struggle, every ounce of effort, worth it. Yet, as I stood at this peak, I realized something: this climb had taken everything from me: my personal life and many of my friendships. I had been so focused on the ascent that life was passing me by. I wasn't finished learning or growing, but the quiet whispers urging me to try something new grew louder. I was burned out, and ready to climb a new mountain. 6

A New Direction At the end of my ninth year, I made the decision to leave behind everything I found familiar - Room 21 at Kate Waller Barrett Elementary. It was time to scale a new summit. I accepted a role in the school district’s human resources office. As new leadership came in, the role evolved with new vision and realignment. Throughout it all, I worked with new teachers and their mentors, leading the district’s novice teacher mentoring program. Leading the new teacher mentoring program for a rapidly growing school district in the aftermath of the pandemic was a monumental task. Much like scaling a mountain requires innovation and problem-solving, developing a program that could adapt to the diverse needs of novice teachers demanded the same level of creativity and flexibility. With the hiring landscape shifting nationwide and varying levels of teacher preparation, I recognized the importance of mobilizing program leaders at each school. We had to create something new. Building relationships, assessing current experiences, and collaboratively shaping a mission, vision, and structured mentoring framework required the engagement and contributions of hundreds across the district. Together, we established a shared experience, strengthened mentor capacity, and extended mentoring support beyond the first year in the profession. The climb was rocky and uneven, challenging everything I thought I knew about myself. Looking back, I see now that it was a journey of self-discovery. But I never reached the summit. Instead, I chose to stop, turn around, and take a new trail. Though I had left the classroom, I remained too comfortable in this role - I still held onto relationships from my teaching years, understood the district’s systems and structures intimately, and felt my personal and professional growth had plateaued. The excitement, passion, and sense of purpose that once fueled me had faded, leaving me feeling lost, as if I had wandered off the beaten path. And once again, the quiet whispers grew louder. Turning Around and Starting Over One day, I set my sights on a new climb. I applied for a new role - Assistant Principal - in a completely different school district. The desire to lead a school had always been part of the whispers that came and went throughout my journey. I was nervous, unsure, and scared. For the longest time, I worried more about what others would think if I left the place that had shaped my early career than my own happiness. It seems so trivial to write this now, but at the time, it was paralyzing. I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I decided to fully live life for myself, but I did. After much encouragement from my partner, I applied. I was no longer worried about what others thought. I was ready to take the leap. 7

In September of this school year, I began a new climb. I was appointed Assistant Principal of a wonderful elementary school in a new school division. Is it too soon to declare that I’ve rediscovered the connection between my passion and purpose? Maybe. But I can tell you this: I’ve never been happier. I wake up each morning with a renewed sense of purpose. This climb feels different. I now better understand how to balance my professional and personal life. I no longer define myself solely by my role as an educator. Being new is one of the most humbling, vulnerable, and fulfilling experiences you can undertake. A new school district. New expectations. New relationships. Vulnerability is where courage shines and dreams are realized. I’m living that reality now. I’m on a hike toward leading a school as principal one day. Each moment, experience, and challenge is a small step toward fulfilling that dream. I love the work I do. Each day, I have the privilege of serving students, families, and teachers in my community. Every moment is different, unique, and deeply rewarding. Hard days still exist, but my passion and purpose are once again aligned. Looking back, I see each day, each experience as a gift. Every interaction, moment, relationship, role, and challenge brought me here. I have no regrets. Society tells us that life is a linear path, but my journey proves otherwise. You don’t climb a mountain by walking straight up - you follow winding trails, navigate rough terrain, and sometimes, you must stop, turn around, and seek a new path. The start of a new trail is exhilarating. Questions to Consider for Aligning Passion and Purpose What brings you joy personally and professionally? Make a list and place a star beside theitems you engage in daily or weekly in your professional practice. If you find that few itemsare starred, your passion and purpose may be out of alignment. What have you always dreamed of doing but haven’t tried yet? Who are three people in your life you could talk to about their sources of joy and passion? When and where are you at your best? Make a list and look for patterns and trends - thesemay point you in the right direction. What are the next steps you can take with sure footing and an eye on your next stop?Dan Reichard currently serves as an Assistant Principal in Fairfax County Public Schools. He has over twelve years of experience in elementary education, professional development, and teacher leadership. From his work as the teacher of the "Room 21 Rock Stars" at Kate Waller Barrett Elementary to leading the development of a beginning teacher support program, Dan is guided by the core values of community, optimism, and excellence. His leadership has earned him several honors, including being named a 2018 Washington Post Teacher of the Year, the 2019 Virginia Region III Teacher of the Year, the 2019 Indiana University of Pennsylvania Young Alumni Achievement Award, a 2023 ASCD Emerging Leader, and a 2024 Worthy Educator Leader. 8

A free service so you can keep current with confidence! Timely updates and action items delivered to your inbox each month! View the March 2025 Advocacy Alert here! Our commitment to your privacy: We will not publish, share or mention you by name or any other identifiable information in supporting your voice as an advocate for public education! 9

When Teachers Tell Their Stories, Change Happens Hannah Grieco, M.Ed., M.F.A., Writer, Editor, Advocate. Columnist, Washington City Paper, Adjunct Professor, Marymount University, Writing Instructor, The Writer’s Center, Washington, DC “When people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain.” -James Pennebaker As teachers, we exist within the push-and-pull of educating vs caregiving. Yes, we’re there to support the learning of our students, no matter their age. But we don’t just teach subjects and skills. We also teach life lessons, as well. Where is the line between learning about Ancient Greece and learning how to communicate effectively? The line between learning to conjugate verbs and developing a healthy skepticism about online influencers? The line between solving for X and advocating for yourself in the classroom and beyond? How does this tightrope walk impact us, as human beings who offer such complicated, layered forms of instruction and care? I am an English professor, but I used to teach elementary school. The difference between six-year-olds and nineteen-year-olds is vast, but their needs are surprisingly similar. They need to feel safe in order to learn. They need to feel respected. They need lessons to be accessible, individualized, and interesting. What about us, though? What do we need, as educators? As we work to support each of our classroom learners, how do we manage our own emotional experience when navigating challenges? Perhaps we face classroom behavior issues or an administrator we don’t mesh well with. Perhaps we have a student who is struggling with mental health needs or trauma in the home. Perhaps there are disabilities we don’t quite know how to support, or a new political landscape taking hold at our school. There are many “what ifs” in teaching and they all seem to end up as weights on the shoulders of us as teachers. How can we process these experiences, find a sense of healing and purpose, and move forward in our work without burning out? Many of us are also looking to go beyond the classroom and make change on a larger scale. We want our schools to be better. We want to help MORE students. We want our teaching to be more effective, more kind, and more inclusive. How do we combine all of these goals and still get to sleep at night? One way to process, heal, and make change is to write about teaching. Not just articles and how-to pieces, but personal essays. Our stories, vulnerable and deeply relatable, can make big changes: both inside us and out there in the world. I wrote about the healing nature of expressive writing for Craft Literary, based on my research at graduate school:In 1986 social psychologist James Pennebaker co-published a research study about the benefits of expressive writing in trauma recovery. His research involved university students writing about specific traumatic experiences for fifteen minutes, four times a week. The results were astonishing. The students who wrote their stories visited the campus student health center 50% less over the next six months versus the students in the control group. “Many students came out of their writing rooms in tears, but they kept coming back. And, by the last day of the experiment, most reported that the experience had been profoundly important for them.” 10

At the time, Pennebaker was focused on physical symptoms. And follow-up studies pointed to improved health as a result of this confessional-style writing. There seemed to be indicators that expressive writing could encourage healing in the therapeutic environment. In 1997, Pennebaker wrote “Writing About Emotional Experiences as a Therapeutic Process”, in which he discussed the natural inclination of humans to tell their stories after an emotional upheaval. He noted that keeping secrets interfered with sleep, health, relationships, and performance at work or school. Hundreds of studies confirmed Pennebaker’s work over the following decades, including one that suggested that trauma actively damages the brain - but “when people translate their emotional experience into words, they may be changing the way it is organized in the brain.” Now I’m not trying to suggest that teaching is a source of trauma. But it’s a mistake to assume we’re immune to the emotional impact of taking care of others. It’s exhausting, even as it’s exhilarating. Sometimes, it’s the greatest gift we’ve been given. Other times, we stumble home and crumple onto the sofa. Occasionally, we experience trauma. Often, we feel misunderstood and alone on this journey. There are so many things we wish parents and politicians knew about the classroom and about the pedagogical choices we make. There are so many times that we wish we could just pull those people in to observe. Look at me love your child! Look at me patiently explain this over and over! Look at me take a quick bathroom break so I don’t lose it, then come back and start all over again. I’m here, fighting the good fight to support and care for these students. Don’t you see? We need them to see. We need to know that we’re not alone on this path. One essay in a newspaper, one poem in a literary journal, and all of a sudden: we are seen. Our needs are more real to them, our students more than just numbers on a page. The key to this transformation in thinking is our own storytelling. Where facts and figures hit a brick wall, sometimes a story of our lived experience can break through. So where do we begin? We start by asking ourselves: Why am I writing this piece?− To inform?− To connect to others or help to establish community?− To convince people of something that I believe?− To make people laugh or feel good?− To make an experience more real for others who may not have experienced it before?− To change something that must be changed?− To help people?Then we askIs this my story? Is this about my life and experience, and my students and their experiences play important parts in the story? Or is this a story primarily about THEIR experience(s), thus their story to tell? We askDoes this story elevate my students, portray even very hard things in a hopeful, generous, and kind light? Or is this embarrassing, shameful, blaming, or overly negative? 11

We askIf my student reads this piece…how will they feel?Will they feel seen? Will they feel loved? Will they feel cared for? Also, we can be particularly thoughtful when writing about students with disabilities and/or lived experiences that we, ourselves, don’t live with. We can use sensitivity readers for pieces (or books!) that are outside our own personal experiences. For example, as the mother of a disabled child, I can speak to being a mother of a disabled child. I cannot speak to being disabled. As a professor, I can write about teaching students with disabilities. I cannot write about HAVING disabilities, and it helps the quality (and impact) of my writing to have a sensitivity reader ensure I’m using appropriate language and examine any potential biases in my writing that I might not be aware of. Some final quick tips Ensure your students stay un-Google-able. (No names and no identifiable photos!) Demand that the publisher utilize appropriate language when discussing disability, illnesses, language needs, poverty, etc.Touch base with your administration about any legal requirements related to visibility, school representation, etc.Consider whether or not you want to use your actual name or a pen name. Privacy is of particular importance when writing at the national level. Some online readers will not be respectful of your privacy! Happy writing! I can’t wait to read all of your stories. References Grieco, H. (February 14, 2024) The Novel, The Map. Craft Literary. The Change Companies. (February 25, 2025) Write Your Secrets: What James Pennebaker Discovered About Expressive Writing. Payne, J. D., Nadel, L., Britton, W. B., & Jacobs, W. J. (2004). The Biopsychology of Trauma and Memory. In D. Reisberg & P. Hertel (Eds.), Memory and emotion (pp. 76–128). Oxford University Press. Pennebaker, J.W. (May, 1997) Writing about Emotional Experiences as a Therapeutic Process. Psychological Science, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 162-166. Richardson, T. (March 8, 2024) Ask an Expert: Sensitivity Reading and Diversity - Getting help from an expert can enhance any author’s work. Publishers Weekly. Hannah Grieco is a writer, developmental editor, teacher, and disability advocate who has published her work in The Washington Post, The Week, Al Jazeera, The Independent, Huffington Post, and many more newspapers, magazines, and literary journals. She writes a monthly column about authors and books for Washington City Paper, and edits novels and prose collections for various small presses. Hannah teaches writing courses at Marymount University and through The Writer’s Center. She led a Worthy Incubator on educator writing and publishing in the autumn of 2024 which is a must watch for anyone wanting to successfully publish opinion pieces in popular journals, papers and online! 12

13 "This experience is really good. I feel like I'm not being judged, so I realize ‘Yes, you're right, this this is what I’m thinking' and I come to conclusions to say, 'Yes, this is what I want. This is what I mean and this is the path that I want to take.’ It's really powerful to be in these conversations with you and Gretchen."-Xatli Stox A Worthy Champion Coaching? P172TB75bA#y1Championing!P172TB77bA#y1Registration for our summer cohort is now open: theworthyeducator.com/championing

What Was The Principal Thinking When She Said That? Carol Ann Tomlinson, Ed.D, William Clay Parrish Professor Emerita, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia In my early years on the faculty of the University of Virginia, and after 21 years in public school classrooms, I taught Catherine who was working on a Master’s Degree in Education. Her dream was to be part of the Muppet company. The degree was in case that didn’t work out. Catherine was great fun to teach. She asked unexpected questions that inevitably made me think - often long after class ended. Her work was consistently creative and multi-layered, integrating multiple aspects of teaching with the world beyond teaching, organized around “big ideas” that spanned times and places and disciplines, and slightly unorthodox. Some of those traits simply reflected who she was as a human being. Some resulted from the fact that she did not major in education in her undergraduate years, meaning that she had never learned to “think like a teacher.” The Muppets gig did not work out, so, degree in hand, she was leaving Virginia, bound for a teaching job in a large school district a little further South. In our final conversation before she traveled to her new job and new apartment, she asked if it would be okay for her to send me journal notes throughout the first year of her teaching pilgrimage, “for feedback - but just if you have time.” That conversation took place about 30 years ago. She did send journal notes. I did respond to them. I still have a copy of her journal and value it as much today as I did during the year we corresponded about the ideas in it. Catherine’s journal caused me to re-think many facets of teaching. Each re-thinking made me a better teacher and a better teacher of teachers. Her journal questions often began with a phrase like, “What do you think (fill in the name/position) was thinking when she asked us to do (fill in the suggestion/mandate); or “Why do teachers do (fill in the blank)”? In her first journal entry, she wrote about the faculty meeting that takes place a couple of days before students return to begin the year. Like many of you, I had attended scores of those meetings during my two decades in K-12 teaching. Long before Catherine mailed that entry to me, I had learned the script. She reported on each aspect of the meeting - sometimes with grim accuracy, sometimes with humor, and sometimes with fresh-eyed puzzlement. The meeting took place on Thursday afternoon of the pre-school week when teachers typically attend a torrent of meetings. Friday was the first and only day teachers would have uninterrupted time in their classrooms before students entered those classrooms on Monday morning. “The principal told us she knew we had more to accomplish on that day than there was time to accomplish it,” Catherine wrote. The principal continued, “Most of you will feel torn between getting your lesson plans in order and getting the bulletin boards and other finishing touches done in your rooms.” She paused long enough to indicate the something important was coming and then concluded the meeting with one final piece of advice. “In case you have any doubt about which of those choices I’d be happiest to see you make, let me clarify that now. Do the bulletin boards!” The question Catherine posed at that point in her narration became familiar to me as the school year and journal shipments continued. “What was she thinking when she said that?” Catherine thought she might have misunderstood what the principal said - or perhaps that the principal was being sarcastic or comedic. I knew the principal was unreservedly serious. I was so accustomed to thinking like a teacher that the only thing surprising about Catherine’s question was that she found the principal’s directive surprising. 14

Responding to Catherine’s journal entries was almost as much fun as our conversations had been. She was clearly thinking creatively and that stimulated my creativity, using analogies, examples from her life and mine, humor, philosophy, images classroom applications, and questions in her responses to the what-was-she-thinking-when-she-said-that kind of queries. My response to the “bulletin board” question, like ones that would follow, often began by explaining how we came to think in a certain way as educators, and followed by saying something like, “but you don’t seem to think that approach would be our best one. Asking yourself why you think “Plan A” is flawed and why you think Plan B, C, or D is more promising is what will be most instructive to you. (What would you hope to accomplish in your work with students that makes “Plan A” seem ill-advised? Why do you feel an alternative approach would benefit your students? Would it benefit all of them alike - or just some? How would you find the answer to that? How does this moment you’re pondering fit into your larger goals as a teacher - your philosophy of teaching?) For both of us, our on-paper dialogue (because online-everything was a bit sparse in the early 1990s) was stimulating and the year passed quickly. Catherine remained a questioning teacher, thoughtful, and challenging. Her creativity didn’t accommodate acquiescing to the “this-is-how-we-do-things-here” script. In time, she became a highly respected, award-winning teacher, a widely admired school administrator, a university researcher and professor for undergraduate and graduate students, and an associate dean. All of that happened not because she learned the scripts she was given as an educator but because she did not! She continues still to ask the question, “Why are we doing what we do the way we do it? What other options might better serve the students in our care and us as their teachers?” The Question Still Needs Asking Catherine’s question has been my companion for 30-plus years and perhaps never in the foreground of my thinking more clearly than it is now. In the past few months, I have been working on a revision for a book whose previous edition is ten years old. That has reminded me daily how much has changed in the past decade. Our world has changed markedly. Our students are different in a myriad of ways than they were ten years back. Research in education is not perfect - that imperfection mirrors the complexity of the job we do and the people we teach - but we have a solid research base that should guide our decision-making as certainly as current research in medicine guides the work of doctors. And yet, we persist in teaching not only like we did ten years ago, or 30. Much of what we do in our classrooms in 2025 mirrors classrooms in the early 20th century and before. Consider the students we serve. Schools vary markedly, of course, so generalizations are just that - broad strokes that represent a whole better than it can represent the complex parts of that whole. In general, however, our students are more diverse than in the past - in cultures and languages, certainly, but also in economic status, adult support systems, past school experiences, exceptionalities, talents, interests, and aspirations, to name just a few descriptors. The students currently in our classrooms also share some earth-rattling experiences that make them similar in important ways. These experiences have dramatically changed many of them and will continue to change them for years to come. Following are a few of the shared, life-altering experiences. COVID-19 Changed Most Young People Our current students and those who will come to us in the near future, have lived through a worldwide pandemic which, for many of them, was traumatizing, for most of them disorienting and disruptive. COVID-19 added thick layers of anxiety to the lives of many young people who were already more stressed and anxious than their peers in earlier decades. As the pandemic persisted for many months, young people experienced stress related to absence of normal routines and parental stresses including job loss. Some students experienced deaths - even multiple COVID-related deaths of family members, friends, and community members. Students of all ages often experienced sleep disturbances, isolation, and depression. They frequently spent more time engaged with screens and less time in physical activity and playing or “hanging out” with peers. Most, if not all students were impacted academically to some degree, with the youngest students generally more negatively impacted than older students, students from low-income families more negatively impacted than those from middle- or upper-income families, and math achievement generally more negatively impacted than reading achievement (although deficits in both areas are problematic in terms of students continuing academic development and will likely remain so for years into the future). LGBTQ students reported greater levels of emotional abuse by a parent or caregiver and having attempted suicide at a higher rate than their counterparts (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2022, March). 15

Some students experienced positives stemming from the extended time away from school such as extra time with parents and time to pursue some personal interests. Many, however, returned to school with impactful social and emotional challenges as well as learning challenges. Teachers of young children found that some could barely speak, were not toilet-trained, had not developed fine motor skills necessary to hold or manipulate a pencil, were not able to sit at a table, and could not verbally communicate with peers. Many students of all ages evidenced poor social skills, inability to regulate emotions, short attention spans, and/or anxiety when asked to work or communicate with peers. In some schools, a noteworthy number of students simply have not come back to school (Center for Disease Control, 2022; Chang, 2025; Miller & Mervosh, 2024). Even though the return to school following the pandemic was, in many ways, an invitation to change the ways we teach to be better suited to the nature and needs of those students, we have largely persisted in how we do school, even as those practices seem less well-suited to post-pandemic learners than they were even to pre-pandemic students. Climate Change is a Threat to Today’s Students The current generation of students includes the first “climate anxiety” babies - children born into a world more deeply aware of the dangers that threaten the planet we live on than any generation before them. They understand acutely that they will almost inevitably pay a heavy price for damages done by earlier generations. While climate change has far-reaching implications for the health and futures of current children and young people, they have little power to limit its harm. Fifty percent of young people in a survey of over 10,000 reported feeling sad, anxious, powerless, helpless, and guilty related to climate change. Many say their daily lives are negatively impacted because of those feelings, including irritability, poor concentration, and insomnia. Seventy-five percent of those surveyed in one large study say the future is frightening to them (Hickman, 2021). Many of these young people are losing, or have lost, faith in their governments. As one author observed, “When the future of all living things is in danger, it is difficult not to feel depressed.” (The Lancet, 2022). Social Media Have Powerful Impacts on Young People Most of today’s students have never experienced life without social media. While most social media apps require users to be at least 13 years old, nearly 40% of children 8-12 years old and 95% of young people 13-17 years old report using social media apps. Teens report spending an average of nearly 5 hours a day on social media (Cleveland Clinic, 2024; DeAngelis, 2024). These media can offer numerous benefits to young users including outlets for additional learning, creativity, connection with old friends and opportunity to make new friends, as well as to be part online communities of people who share their interests, talents, life experiences, challenges, and concerns. Social media can facilitate identity development, offer opportunities for civic and community engagement, and provide social support for young people. (Annie E. Casey, Foundation, 2024; Mayo Clinic Staff, 2024; Weir, 2023). Use of social media comes with significant risks as well as an array of benefits. Rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide in young people that were rising before COVID intensify when social media use becomes a negative in a young person’s life. For example, overuse of technology can lead to issues such as: low academic performance, difficulty paying attention and concentrating, low creativity, delays in language development, delays in social and emotional development, physical inactivity and obesity, social incompatibility with others, and aggressive behaviors (Johnson, 2024). Cyberhate, cyberbullying, racial bias, racism, illegal and explicit content, misinformation, hate speech, and content that supports unhealthy behaviors such as substance abuse and self-harm are realities in the virtual world that extend beyond the maturity levels of children and teens. Artificial Intelligence will Change Everything in Students’ Lives The discovery of fire, invention of the wheel and later the printing press, harnessing of electricity, and invention of computers and creation of the internet are examples of waves of technology that transformed civilizations, altering power structures in their wake. Experts tell us we are about to see the greatest redistribution of power in history through widespread use of AI (Thomas, 2025). Artificial intelligence can be available to anyone, not just a wealthy or privileged few. And this reshuffling of power, the greatest one in history, is unfolding in the space of just a few years (Suleyman, 2023). In the biological sciences, inventions and breakthroughs that would now take 50-100 years will be possible in a 5-10-year span using AI. In schools, AI will change the way humans of all ages learn. Its use of machine learning, natural language processing, and facial recognition can help digitize textbooks, detect plagiarism, and gauge the emotions of students to help determine who’s struggling or bored, and provide print materials in hundreds of languages in an instant, helping teachers meet students where they are in learning and understand how to help each of them move forward efficiently and effectively (Thomas, 2025). 16

There are, of course, disruptive and potentially calamitous negative consequences associated with AI. It is likely that 44% of current workers’ skills will be taken over by technology or become obsolete all together. Human biases, already detected in AI, reflect the biases of the people who train the algorithmic models. If this trend continues, AI tools will reinforce existing biases and perpetuate social inequalities. The spread of deepfakes and misinformation blurs the line between truth and deceit, making misinformation a threat to individuals and entire countries alike. We see that already in use to promote political propaganda, commit financial fraud, and place individuals in compromising positions. Further, security breaches to data privacy threaten safety, legal rights, and intellectual property rights (Thomas, 2025). Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of AI at this point in its development is that it is readily availability to virtually anyone who wants it and is, at this point, unmanaged. “Whether it’s commercial, religious, cultural, military, democratic, authoritarian, every motivation you can think of, can be dramatically enhanced by cheaper power at your fingertips. And it’s coming faster than we can adequately prepare for it” (Suleyman, 2023). Societal Polarization and Fracturing Lead to Unhealthy Levels of Uncertainty The United States is operating currently in a fractured and polarized state which makes it almost impossible for various stakeholder groups to agree on even the most foundational elements like who we are as a people, the root system of our government, and how we move forward in ways that are mutually productive rather than mutually destructive. Polarization is not another word for a disagreement about how to solve public policy problems. Such disagreements are natural and healthy in a democracy. Our current polarization results in our not wanting to have neighbors who don’t share our views, not entertaining ideas that don’t align with our own, seeing life as a zero-sum game in which negotiation and compromise are perceived as betrayal. We demonize one another and loathe those whose views differ from our own. (Jilani & Smith, 2019). We feel pressure to conform to our groups, find it almost impossible to engage in healthy dialogue, and are more antagonistic and violent toward one another, less likely to help one another out, and more likely to see deception and lying as acceptable tools to use against those we see as our enemies. Our government is in gridlock, which damages its institutions, including schools, and causes people to lose trust in those institutions they once trusted to serve their best interests. As a result, our physical health is probably suffering as our level of stress continues to escalate (Jilani and Smith, 2019; McDonald, J. 2022). It is not surprising that young people are acutely aware of and suffering from these divides that seem virtually impossible to bridge. They, too, feel pressure to conform to the beliefs, attitudes, and practices of their “tribe.” In many schools, there is more animosity among students, greater unwillingness to listen to “the other,” and more acting out through the use of angry rhetoric, bullying, and other manifestations of their own anxiety and disequilibrium. Teachers often feel they teach in the bullseye of the larger societal conflict. Often, they do. The young people we teach are products of these major life forces and upheavals. They come to school carrying the weights of the impacts. They need their schools and teachers to understand that the ground beneath their feet is moving, that they feel ungrounded in many ways, and that long see a future that feels inviting to them. They are our students. We are their teachers. 17

Consider our Response to the Young People in our Care I have great faith in teachers. They have taught me that trust as I have worked among them for over 50 years. I believe that if we sat together in a conversation about how we could best respond to the kids who bring the residue of COVID, climate change anxiety, stresses and threats of social media, the looming changes of artificial intelligence, and the uncertainty and rancor spawned by social and political fractures, along with the immense challenges of growing up even in the best of circumstances, we might make suggestions much like these: They need, first and foremost, classrooms and teachers who are genuinely excited about teaching and learning from them - places where: − they feel safe, seen, known, appreciated, and valued, − their teachers work daily to know and understand them more adequately, more deeply, as individuals, − they feel a sense of community and a responsibility for contributing in positive ways to the welfare of that community and each member of it, − each of them is viewed as capable of doing great things, where expectations for their work are very high, and where there are reliable support systems that help them meet and exceed those expectations, − they work in partnership with their teacher and with one another to create a classroom that contributes to the success of every member of that classroom, − they encounter and contribute to joy every day. These students also need to engage with curriculum that inspires them and motivates them to invest the hard work of learning; curriculum that: − helps them make sense of what they are learning and of the world around them, − feeds their curiosity, − connects with their experiences, cultures, talents, interests, and aspirations, − supports them in seeing the interconnectedness of everyone and everything in life, − prepares them to do authentic work in each discipline, − empowers them to be problem-solvers, and creators, − demonstrates to them regularly that they can have an impact on the world outside the classroom door, − invites them to shape what they will learn and how they will learn it, − helps them realize, over and over again, that learning is a human gift which makes life richer and that enables them to walk with confidence in their world. These young people, at all ages, need to experience assessment more as mentoring than judging. They need assessment that helps them: − seek clarity about learning goals and how those goals align with success criteria, − develop the attitudes and habits of mind that lead to success in learning and in life, − see how mistakes can be their partners in learning, − express learning in a variety of modalities, − compete against themselves as learners and take their own next steps in learning every day, − ask questions that move their learning forward, − develop agency and independence as learners and thinkers. − value growth more than a stationary, unitary, and often arbitrary indicator of performance. 18

These young people need to learn in ways that feed them academically, intellectually, affectively, and socially. They need instruction that: − establishes high expectations for quality work, − mentors learners to achieve high quality work, − is responsive to student strengths, readiness needs, interests, cultures, and learning preferences, − provides consistent, regular time and support for students to take their own next steps as learners, − is active, − is collaborative, − is connective, − helps them make meaning of what they learn, − invites them to make suggestions and choices about how they learn, − helps them organize what they learn for remembering, applying, transferring, and creating, − calls on them to work, think, and assess the quality of their work like experts in a field. These descriptors of teaching that enlivens, nurtures, challenges, and supports young people are representative of the research base that defines our profession. They also point toward the kind of education most likely to prepare students for meaningful engagement in their present and future worlds (Tomlinson, 2021). I believe this is the vision of teaching that drew many teachers to enter teaching as their life’s work. K-12 classrooms that represent this vision are not wholly absent, but they are, in my experience, uncommon. Consider our Current Responses to the Students in our Care Schools and teachers within those schools are as varied as the students we teach, so there is no single profile that captures how every classroom operates - how every classroom responds to the young people who come there every day. Nonetheless, I would argue that there is a profile that is broadly applicable across schools and classrooms. Classrooms that match the profile are characterized by many or most of these descriptors: − The mission of the class is to raise standardized test scores. − The curriculum is largely focused on coverage of standards. − Subjects that will not be tested are valued and taught less (if at all) compared to subjects around which the standardized tests are designed thus limiting the scope of learning for many or most students. − Instruction centers on practicing basic (foundational) skills that are enumerated in documents that delineate and support the standards, and that govern the development of standardized tests that will judge student and teacher performance. − There are far more standards that teachers are expected to cover than there is time to address at more than a surface level. − To ensure that teachers in a specified grade level or content area provide students with the same instruction, teachers are often mandated to follow pacing guides that define what every teacher should be teaching at a given time. − Teachers struggle to reconcile mandates to adhere to the pacing guide, to accept the reality that their students’ worth and their own will be based in large measure on a standardized test - and simultaneously, to address student variance by differentiating instruction. − Of necessity, instruction becomes teacher-centered, low level in terms of student reasoning, time- and test-driven, and frequently regimented. − Teachers in middle and high school often feel strongly that between the number of students they teach, the need to “cover” vast amounts of content, and the pressure to have students perform well on one or more standardized tests, there is no chance to address student readiness or interests - or even to provide alternative ways for students to express learning. Not only is there too much to “cover” in too little time, but the test won’t make those accommodations available, therefore it seems counterproductive to provide them. 19

In the United States, we have placed standardized test scores at the center of teaching and learning in public schools for over 30 years. During that time, it seems fair to say that earnest, hard-working teachers have done their very best to honor the mandates that surround the standards and the standardized tests themselves. If that diligence had resulted in consistent, significant improvements in test scores (which could arguably be different from improvements in learning), then it would be possible to make a case, if not a robust one, that the efforts of teachers and students had been worth the cost. That is not the case. There are occasional increases in certain scores at certain grade levels in particular locations on high stakes tests. There is no evidence, however, that students as a whole are doing better on the state standardized tests, or on other standardized tests (for example, AP, IB, NAEP, TIMMS) whose scores might have been positively impacted if student learning had risen as a result of the state tests. There is an argument - or multiple arguments - to be made that the single-minded focus on test scores has caused significant harm to students and their teachers: − Elementary students often experience higher levels of anxiety and lower levels of self-confidence in the face of standardized tests - including irritability, frustration, boredom, crying, headaches, and loss of sleep. When they were asked to draw pictures of their test-taking experience, nearly all the drawings suggested a negative experience. They showed students who were nervous about not having time to finish the test, not being able to figure out the answers, and not “passing” the test. Researchers who examined the drawings noted that in nearly every drawing, children drew themselves with unhappy or angry faces. Smiles were nearly non-existent. When they did occur, they related to things like being able to chew gum during the test or an ice cream party that would follow the test (Terada, 2022). − The tests do not measure what we sometimes call “soft skills” like knowing how to learn effectively, willingness to take academic risks, or persisting in the face of difficulty; nor do they assess complex thinking, creativity, ability to navigate relationships with others, and many other skills and mindsets that are valuable in students’ current and future lives (Terada. 2022). − When rewards and sanctions are attached to performance on tests, students become less intrinsically motivated to learn and less likely to engage in complex learning and critical thinking (Berliner, 2003). − High stakes tests cause teachers to take more control of learning experiences, denying students to learn to direct their own learning and explore topics and concepts that are interesting and relevant to them and can obstruct their progression to becoming lifelong learners (Berliner, 2003). − Students who consistently score in the bottom quartile of standardized tests are more likely to drop out of school, even when those students have acceptable academic records (Amrein-Beardsley & Berliner, 2003). − High stakes tests have often reduced curriculum to a list of facts and fundamental skills separate from any meaningful context or application. − Teachers who are compelled to gear the great majority of their classroom efforts to raising test scores have little, if any, motivation, support, or opportunity to develop their own creativity, at least insofar as it might be useful in teaching. − Rather than being at the center of instructional decision-making as they should be, students have become collateral damage of an outdated, ineffective, non-responsive, mandate-driven teaching. 20

Channeling Catherine I see Catherine occasionally and always joyfully! I think about her much more often as I find myself worrying about teachers, teaching, learners, and learning. I find myself asking, almost as though the question were stuck on “repeat”: − What are we thinking when we teach as though all our students are essentially alike, when we assume they all need us in pretty much the same way? − What are we thinking when we push to the corners of our consciousness the weights virtually all our students bring to the classroom every day because we can’t find time to engage with them about their hopes and fears and anxieties? − What are we thinking when we say, “I’m sorry. I have no choice but to teach as though a test is more important than the humans in my classroom - more important than their humanity”? I understand the relentless pressure teachers feel to “follow the script.” I understand the cost of following the script in terms of job satisfaction, worry about students, and personal growth. I am not untethered from reality enough to say, “Just forget about the test,” although I applaud courage when I see teachers move in that direction - even in small steps. I do believe it is possible to integrate the foundational knowledge and skills that are central to the disciplines we teach into work that inspires young minds so that we are “accountable for the standards” and for the well-being of the well-being of those we teach. I do believe we can organize what we teach in ways that make it more memorable, relevant, meaningful, and useful. I do believe it’s possible to make a profound difference in the welfare of our students when we say, ‘Today, I will build in time for these learners. Tomorrow I will do it again.’ I do believe we can create community, teach empathy, enable students to work together in harmony and productively - all elements that today’s young people hunger for in their bones. I am hopeful that enough of us have managed not to so completely learn the script for “how we do things around here” that we will be able to ask Catherine’s question of ourselves, among like-minded colleagues, of leaders, and in public forums: “What are we thinking when we (fill in the blank with what matters most). “ ” 21

References The Annie E. Casey Foundation (June 23, 2024) Social Media and Mental Health. Blog. Berliner, D.C. (February 1, 2003) A Research Report: The Effects of High-Stakes Testing on Student Motivation and Learning. ASCD, Educational Leadership. Amrein-Beardsley, A. & Berliner, D.C. (January 1, 2002) An Analysis of Some Unintended and Negative Consequences of High-Stakes Testing. National Education Policy Center. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (March 31, 2022) New CDC data illuminate youth mental health threats during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cain, C. & Mervosh, S. (July 1, 2024) The Youngest Pandemic Children Are Now in School, and Struggling. New York Times. Chang, L. C., Dattilo, J., Hsieh, P. C., & Huang, F. H. (2023). Gratitude mediates the relationship between leisure social support and loneliness among first-year university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. Journal of Leisure Research, 56(1), 1–20. Cleveland Clinic. (January 15, 2024) How Social Media Can Negatively Affect Your Child. Health Essentials. DeAngelis, T. (April 1, 2024) Teens are spending nearly 5 hours daily on social media. Here are the mental health outcomes. American Psychological Association. Vol. 55 No. 3. Hickman, Caroline et al. (December, 2021) Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, Volume 5, Issue 12, e863 - e873. Jilani, Z. & Adam Smith, J. (March 4, 2019) What Is the True Cost of Polarization in America? Greater Good Magazine. Johnson, H. (Mar 8, 2024) New study finds connection between kids' screen time and delayed language development. WXOW.com. Mayo Clinic Staff. (January 18, 2024) Teens and social media use: What's the impact? In Depth Healthy Lifestyle: Teen and Tween Health. McDonald, J. (November 30, 2022). Political conflicts are having a chilling effect on public schools. UCLA School of Education & Information Studies. Political Conflicts are Having a Chilling Effect on Public Schools - UCLA School of Education & Information Studies Suleyman, M. (September 7, 2023) Transcript: The Path Forward: Artificial Intelligence with Mustafa Suleyman. The Washington Post. Terada, Y. (October 14, 2022) The Psychological Toll of High-Stakes Testing. Edutopia. Thomas, M. (January 28, 2025) The Future of AI: How Artificial Intelligence Will Change the World. Built In. Tomlinson, C. (2021). So Each May Soar: The Principles and Practices of Learner Centered Classrooms. Alexandria, VA: ASCD. Weir. K. (September 1, 2023) Social media brings benefits and risks to teens. Psychology can help identify a path forward. Monitor on Psychology. Vol. 54 No. 6. Yamamoto, M., Mezawa, H., Sakurai, K. et al. (September 18, 2023) Screen Time and Developmental Performance Among Children at 1-3 Years of Age in the Japan Environment and Children’s Study JAMA Pediatrics. 2023;177(11):1168-1175. Carol Ann Tomlinson taught in public schools for 21 years and was later a faculty member at the University of Virginia for 30 years. Her two “lives” as an educator have enabled her to develop, pilot, research, refine, and share a model for “differentiating instruction” in today’s diverse classrooms. The model supports teachers in recognizing and addressing students’ varied strengths, needs, interests, cultures, and school experiences to maximize each learner’s possibilities. Carol was Virginia’s Teacher of the Year in 1974 and received an All-University teaching award at the University of Virginia in 2008. Since 2013, she has been ranked in the top 20 of Education Week’s Edu-Scholar Public Presence Rankings of the 200 “University-based academics who are contributing most substantially to public debates about schools and schooling,” and in the top 5 voices in Curriculum. . 22

23 Reclaiming the Mantel of SEL! New features monthly at P536T 8 bA#ytheworthyeducator.com/xselerated

Reimagining and Innovating the Delivery of Education in Wyoming R.J. Kost, M.Ed., Executive Director, Wyoming ASCD, Member, Wyoming State Board of Education, Former State Senator, District 19 Wyoming Legislature, Powell, Wyoming In a world of changing attitudes around education in Wyoming and around the country, the Wyoming Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (WY-ASCD) has made shifts from the pre-COVID era to today’s post-COVID world. WY-ASCD struggled during and since the pandemic with districts focusing on internal challenges, from online learning to absences to failures, forced to respond in ways for which we were not prepared as teachers, curriculum directors, and administrators, and the unanticipated negative and counterproductive implications have created less than desirable learning environments for our students. A bit of information for those who might be reading this from outside of Wyoming. We have 48 school districts statewide and many are pretty small, so curriculum directors can be wearing two or more hats, which can make it hard to completely focus on their primary responsibilities. We have a total of about 92,000 students across the state and we cover a lot of miles between districts, so it isn’t easy for a small district with only one teacher per grade level to connect with colleagues and have input. In many cases, that sole teacher can feel like they are stranded on an island. Working to get them in touch with educators in other similarly sized districts can help address this sense of isolation. With all this in play, we decided it was time to become more active and help all directors in the state not only understand the focus and purpose of WY-ASCD, but to feel they are all an important and active part of the association. But how? Charlotte Gilbar, president of WY-ASCD, developed the executive committee with the including our president, president elect, treasurer, secretary, and past president initiated monthly online meetings for district and regional curriculum directors. Wyoming is divided into five regions, with representation from districts of all sizes, which translates into an additional ten extra seats on our board. Another strategy was to enhance in-person professional learning. We have always had a fall and spring conference, but attendance was dwindling during and since the COVID-19 disruption. So in the summer of 2024, we decided to partner with our state elementary principals’ association, secondary principals’ association, and special education association so that our conferences can provide better breakout groupings while expanding our capacity and offerings of speakers and sessions. This has proven to be a great success, with an increase in attendance and membership. Since many administrators in our small districts wear multiple hats, joining relevant organizations can provide necessary supports while being efficient with time and travel. 24 P549TB134#y1Click here to view the total district implementation of RIDE in Park County School District #6 in Cody! P553T 35#yClick here to view RIDE implementation in Park County School District #1 in Powell!

This spring, our conference will focus on meeting the needs of curriculum directors as they begin to plan for the next school year, bringing in the State Board of Education to report on its current work and introduce new officers. The Wyoming Department of Education will also attend and present what is changing federally and how it impacts our state since the state legislature has convened. Many of the bills introduced will have a direct effect on schools’ daily operations, as well as the other areas legislators feel need attention. The information provided at the conference will help everyone attending stay current, ask questions and get answers that help them effectively plan for these coming changes. WY-ASCD anticipated these shifts in education happening at the state level, and we have been strategizing since the 2023-2024 academic year to strengthen our reputation in the state as a trusted partner educators can rely on for direction, support, and assistance during this time of change. The State Board of Education tasked to develop a Profile of a Graduate, our governor appointed a group to focus on making innovative changes in education by developing the project entitled “Reimagining and Innovating the Delivery of Education” (RIDE, for short). Andrea Gilbert, the curriculum director for Converse County School District #1 in Douglas, Wyoming describes how RIDE looks in some districts: “Governor Gordon's RIDE program, supported by expert consultants from 2 Revolutions, is transforming Converse County School District's assessment practices by integrating engaging performance assessments into a balanced system. These assessments, designed to be more dynamic and comprehensive than traditional tests, require students to demonstrate their understanding through real-world tasks that align with multiple standards. Teachers have adapted their instructional strategies to focus on student choice and voice, fostering a more personalized learning experience. This shift has also better prepared students for more rigorous summative assessments. The program has encouraged cross-curricular collaboration, uniting core subjects with specials like the arts, STEM, computers, library, and PE, enriching the learning process and providing a holistic education that bridges subjects and skills.” After holding sessions around the state listening to educators and public education stakeholders, the State Board of Education decided to reduce the number of standards in each content area, which continues to be a gigantic undertaking. The table at the top of the next page breaks down the standards reduction in six of ten state content areas from 386 to 140, with math and science standards reduced by the largest percentages. WY-ASCD is stepping up to make a huge difference in the outcome of these reductions and helping to provide support for successful implementation. WY-ASCD is having our curriculum directors connect with their classroom instructors to review the reductions in standards and what they mean for the continuity and quality of instruction. As a result, the changes and their implications are better understood by everyone involved, and curriculum directors have the necessary buy-in from educators and stakeholders to support an effective rollout. 25

In 2023, the Wyoming State Board of Education asked the WY-ASCD to form a state Curriculum Directors Advisory Committee (CDAC). The CDAC was asked to get information out to the staff of each district and receive their input. Our monthly online meetings proved to be very productive, with everyone indicating the value of our collaboration made a significant difference in the process. The President of the WY-ASCD Curriculum Directors, Charlotte Gilbar explains the work of the CDAC. Charlotte is the Executive Director in Natrona County School District #1 in Casper, Wyoming: 26 “The Wyoming Curriculum Director's Advisory Committee (CDAC) plays a pivotal role in shaping the state's educational standards and rules. Composed of a representative group of curriculum directors and educational leaders from various school districts, CDAC is a committee that was formed by the Wyoming State Board of Education (SBE). The CDAC also collaborates with the Wyoming Department of Education (WDE) to review, audit, and recommend modifications to the state's content and performance standards. Key Responsibilities: Standards Review and Recommendations: CDAC evaluates existing educational standards across the ten content areas Math, English Language Arts, Science, Social Studies, Computer Science, Physical Education, Health, World Language, Career and Technical, and Fine & Performing Arts. The committee reviewed proposed changes to the Math and Science Standards, leading to a 61% reduction in K-12 Science Standards and a 64% reduction in K-12 Math Standards. Provide Feedback: The CDAC reviewed feedback on the proposed Wyoming Math, Science, Computer Science, Fine and Performing Arts, Health and PE Standards that were gathered through surveys and virtual public meetings by the SBE and WDE, ensuring that community perspectives inform educational decisions. Impact: Through its collaborative efforts, CDAC collaborates with the SBE to help ensure that Wyoming's educational standards are rigorous, relevant, and responsive to the needs of students and educators. By integrating public input and expert recommendations, the committee plays a crucial role in maintaining high-quality education across the state.” P582TB141#y1Students visiting the Wyoming State Capitol in Cheyenne.

The SBE's work to reduce standards is intended to provide greater focus on essential learnings while making room and providing flexibility for schools to implement the vision of the Profile of a Graduate: The powerful combination of the innovation of the RIDE project with the reduction in standards and the connection to the profile creates many questions, challenges and opportunities, and WY-ASCD is positioned as a leader in this implementation work. The question is how to merge the standards with the profile to best identify graduates. Each district’s accountability documents are being developed to meet state and federal requirements while allowing for local control, and we are working with curriculum directors to identify optimal solutions. 27

While the performance of our state compared to the nation is good, we are focused on finding ways to have an even greater impact on our students, and our state legislature who is asking to see an even better return on the investment in our schools. The three major changes we have discussed here task curriculum directors with much of the responsibility for implementation, under the direction of the Wyoming Department of Education and the State Board of Education, and WY-ASCD is a proud partner in this important work. Our collective goal is for students to be more excited, more engaged and more in control of their learning, connecting what is being taught about the world in which they live with their aspirations for the future. An important additional consideration is the connection between career and technical education (CTE) and the academic standards all students should master. We feel we are on the right track there, as well. Whether it be a certification, an associate’s or bachelor’s degree, or entering directly into the work force post-graduation, we are working to provide each student with a quality education and the ability to achieve their dreams. As we implement the combination of the RIDE program, the reduction in standards, and the Profile of a Graduate, we must provide the flexibility and support that our instructors, their curriculum directors, and our district leaders need to implement new approaches that break free of the industrial-age practices to which we have been beholden for the last century. WY-ASCD continues to be the leading voice in the education of Wyoming students, tackling challenges and growing membership as we engage with all of the districts in our state. As we reimagine the future, it is bright with educational innovation empowering our students to fulfill their potential and achieve success in school and in life. References Bernasconi, B. (December 19, 2024) Wyoming: When Dreams Become Reality. 2 Revolutions. Gordon, M. (2024) RIDE Board Members. Office of the Governor. Gordon, M. (2025) Reimagining and Innovating the Delivery of Education. Office of the Governor. Gordon, M. (2024) Wyoming’s Future of Learning Application. Office of the Governor. P603T 37#yCredit: Sonya Tysdal, Curriculum Director, Weston County School District #1 28 P6 5T 40#yShop class as a feature of RIDE implementation in the Park County School District #6 in Cody

R.J. Kost has served as Wyoming state senator for District #19 (Big Horn and Park Counties) from 2019-2022 and in 2023 he was appointed to the State Board of Education. As executive director for the Wyoming Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (WY-ASCD), he helps lead Wyoming curriculum directors in reimagining the delivery of education to their students. Thank you to each of these outstanding leaders in Wyoming education who contributed to this article:Tim Foley Assistant Superintendent Park County SD #6 Cody, WyomingCharlotte Gilbar Executive Director Natrona County SD #1 Casper, WyomingAndrea Gilbert Assistant Superintendent Converse County SD #1 Douglas, WyomingPaige Fenton Hughes Superintendent Converse County SD #1 Douglas, WyomingVernon Orndorff Superintendent Park County SD #6 Cody, Wyoming Sonya Tysdal Curriculum Director Weston County SD #1 Newcastle, Wyoming 29

Friday, April 18, 2025 1:00 – 2:00 p.m. e.t. Dr. Thomas Hoerr and Dr. Melinda Bier are pleased to announce their new doctorate program in Character Development, Social Emotional Learning, and Leadership, beginning in fall 2025 at the University of Missouri in St. Louis. The program is designed to help educational leaders, regardless of their title or role, become more effective and help others grow. Believing that who you are is as important as what you know, their program focuses on enabling students to make a positive difference in their organization, school communities and the world through personal and professional transformation. Students will create dissertation topics that stem from their passions and enable them to become experts in the field. 30 For the First Time, Earn a Dedicated Doctorate in SEL, Character and Leadership! P674T 9 bA#yJoin Tom and Mindy to learn more and add your voice to the discussion! theworthyeducator.com/a-worthy-incubator-on-sel-in-leadership

Real World Learning: Civic Engagement for Students from the Bronx and Philadelphia Jeffrey Palladino, M.Ed., Principal of Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School, Bronx, New York “I really like it here. I feel like I belong at a place like this!” twelfth grader Rasaun Hill told me on a beautiful October day on the campus of Temple university in Philadelphia. I have known Rasaun for the past four years as his Principal at Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School (FLHFHS) in The Bronx, New York. So why were Rasaun and I on the campus of a University 2-and-a-half hours away from our school? Well, the easiest answer is: BPL Votes. Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School is one of 275 schools that are part of the Big Picture Learning (BPL) global network. BPL schools focus on going beyond the school campus to learn by bringing community into the classroom. Forty students and four staff members from Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School (FLHFHS) made the early morning trip down to Philadelphia to meet up with students from Vaux High School and El Centro de Estudiantes, two of our sister schools from Big Picture Philadelphia. Together we were part of the initial group of schools participating in BPL Votes, an initiative created by Fannie Lou Hamer alumni Naseem Haamid. Naseem, a civically active student since his freshman year in high school and now in his last year of law school, who created BPL Votes to engage, educate and empower the Big Picture Learning Network in the electoral process. Naseem conceived this idea last summer through conversations with Joshua Poyer of Big Picture Learning and members of the Fannie Lou team, discussing how we could involve students in civic education during the 2024 presidential election. There we were on October 8th, just under a month from election day, with eighty students canvassing Philadelphia reminding citizens of their voting rights, registering them to vote and making sure they were prepared to follow through and vote on election day. It was one of the most powerful moments in my close to thirty years in education. In late August, I had received an email from Naseem expressing how much he wanted to engage students in the electoral process of the quickly-approaching election. Going to a school named after arguably one of the greatest civil rights leaders in our history, our students are well-versed in the work of Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer registering African-Americans in the south to vote. Since we also use classwork, extracurricular activities and internships to focus on community organizing and civic engagement, Naseem’s passion fit nicely into our mission. His pitch was to connect FLHFHS with another school in the network, preferably from Big Picture Philadelphia because of the importance of Pennsylvania in the upcoming election. We knew from the outset that the project had to be non-partisan with the focus of increasing voter turnout, especially among young voters. We enlisted two of our internship teachers, Aaron Broudo and Juvanee Bedminister, who were immediately on board. Now we needed partners in Philadelphia to see if we could make Naseem’s dream a reality. 31