Return to flip book view

JournalVOLUME 103 2024 ISSUE 2WWW.INDENTAL.ORGThe JOURNAL of the INDIANA DENTAL ASSOCIATIONCHALLENGES OF ACADEMIC LIFE IN DENTAL SCHOOLS PAGE 20COMBATTING COMPASSION FATIGUE PAGE 43STATE OF DENTAL LICENSURE 2024 PAGE 36Dental School in 2024 | PAGE 12IDA Message

The Journal is owned and published by the Indiana Dental Association, a constituent of the American Dental Association.The editors and publisher are not responsible for the views, opinions, theories, and criticisms expressed in these pages, except when otherwise decided by resolution of the Indiana Dental Association. The Journal is published four times a year and is mailed quarterly. Periodicals postage pending at Indianapolis, Indiana, and additional mailing oces.ManuscriptsScientic and research articles, editorials, communications, and news should be addressed to the Editor: 550 W. North Street, Suite 300, Indianapolis, IN 46202 or send via email to kathy@indental.org.AdvertisingAll business matters, including requests for rates and classieds, should be addressed to Kathy Walden at kathy@indental.org or 800-562-5646. A media kit with all deadlines and ad specs is available at the IDA website at www.indental.org/adverts/add.Copyright 2024, the Indiana Dental Association. All rights reserved.Journal IDAPersonnelOfficers of the Indiana Dental AssociationDr. Lisa Conard, PresidentDr. Rebecca De La Rosa, President-ElectDr. Lorraine Celis, Vice PresidentDr. Will Hine, Vice President-ElectDr. Jenny Neese, Speaker of the HouseSubmissions Review BoardDr. Rebecca De La Rosa, AvonDr. Caroline Derrow, AuburnDr. Steve Ellinwood, Fort WayneDr. Karen Ellis, Co-EditorDr. Sarah Herd, Co-Editor Dr. Joseph Platt, Vice Speaker of the HouseDr. Nia Bigby, TreasurerDrs. Karen Ellis and Sarah Herd, Journal IDA EditorsDr. Thomas R. Blake, Immediate Past PresidentMr. Douglas M. Bush, Executive Director, SecretaryDr. Jerey A. Platt, IndianapolisDr. Kyle Ratli, IndianapolisDr. Elizabeth Simpson, IndianapolisKathy Walden, Managing Editor

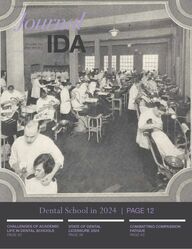

4 Editor’s Message Dr. Karen Ellis 6 IDA President’s Message Dr. Lisa Conard 8 Immediate Past President’s Message Dr. Tom Blake 10 Executive Director’s Message Mr. Doug BushCover Story 12 Finding My Calling: My Journey to Academia Dr. Elizabeth Simpson 14 A Day in the Life: IUSD Students in Their Own Words Dr. Elizabeth Simpson 20 Challenges of Academic Life in Dental Schools: A Faculty Perspective on Connecting All the Pieces to Succeed Dr. Priya Thomas, Dr. Monica Gibson, Dr. Chandni Batra, Dr. Hawra AlQallaf, Dr. Neetha Santosh, Dr. Celine Cornelius, Dr. Halide Namli, Dr. Vanchit John 24 The State of Dental Curricula: Are We Preparing Students for Today’s Practice and Academic Life? Dr. Chandni Batra, Dr. Celine Cornelius, Dr. Monica Gibson, Dr. Hawra AlQallaf, Dr. Priya Thomas, Dr. Halide Namli, Dr. Neetha Santosh, Dr. Vanchit John 30 Mental Health: A Review of Dental Schools and their Mental Health Initiatives for Dental Students Dr. Monica Gibson, Dr. Celine Cornelius, Dr. Neetha Santosh, Dr. Hawra AlQallaf, Dr. Chandni Batra, Dr. Halide Namli, Dr. Priya Thomas, Dr. Vanchit John 36 State of Licensure 2024 Dr. Jill Burns 38 Dental School from the International Student’s Perspective Dr. Elizabeth Simpson News & Features 43 Combatting Compassion Fatigue as a Dental Professional Dr. Catherine MurphyClinical Focus 46 Diagnostic Challenge: Spring 2024 Dr. Angela Ritchie, Dr. Neetha Santosh Member Zone 50 In Memoriam 51 Classieds 52 New Members 53 Out of the OperatoryCONTENTS Issue 02 2024124346COVER PHOTO:General operatory of the Indiana Dental College, 1924. Reprinted with permission from Indiana University School of Dentistry.

4 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2I was not the child that had to be coaxed or promised special treats to go to the dentist. The hygienist did not have to chase me around the room to get me in to the dental chair. I remember liking going to the dentist. The routine was pretty standard: go to dentist, get treated like a princess and walk away with a toy. But the day I had my lling done (an amalgam placed on the occlusal surface of tooth #14) was especially memorable. I remember that now there were TWO people making a fuss all over me. I remember the movement of the hands and arms over my mouth in a uid movement similar to a maestro conducting a symphony. But what made the visit as vivid then as it is to this day was the mirror that was placed on the overhead light. I was xated being able to watch what was going on. I don’t remember being scared. I just remember fascination about what was going on in the mirror: I could feel my body becoming very still and my eyes growing wide, the bare hands, the back and forth passing of instruments, my mouth open with what seemed like cotton rolls everywhere, the whir of the drill and the plugging of whatever it was in my tooth. My amalgam is still there. It is super tiny. And the whole event probably lasted no more than 10 minutes. But in that moment I felt like time was standing still. That mirror was pivotal in fostering my CURIOSITY. I entered dental school with curiosity and a desire to learn. The four years at Indiana University School of Dentistry were dicult to say the least. As Charles Dickens would open A Tale of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair.” The highs and lows I experienced while a student felt very similar to that. I did not come from a family of dentists and the learning curve was great. I was in SBO5 until 11:30 most nights working on my hand skills. The hazing culture was strong and fear was an absolute motivator. I think I cried nearly every day my second year of dental school and remember being encouraged by upper classmen that “next year will be better.” That wasn’t true. And it wasn’t true for my senior year either. But, I did feel buoyed by the support of my classmates who became Dr. Karen Ellis, Journal IDA co-editorEDITOR'S MESSAGE Pivotal MomentsIT WAS 1980. The year was signicant for many reasons. Mount St. Helens Volcano erupted in Washington State, killing 57 people and causing an estimated 3 billion in damage. The U.S. Hockey team beat the heavily favored Soviet Union 4-3 at Lake Placid, NY in one of the biggest upsets in Olympic history. That same year, President Jimmy Carter announced the U.S. would boycott the summer Olympics in Moscow, Soviet Union in protest of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Pac-Man was released becoming one of the best-selling video games of all time. The Rubik’s Cube was introduced. Blondie released the hit song “Call Me,” which would become the 1980 Billboard Song of the Year. And, it was a national obsession for millions of viewers as they tuned in to watch the television series “Dallas” to learn “Who Shot J.R.?” For me, the year was signicant because that was the year that I had my rst (and only) cavity lled.ABOUT THE AUTHORDr. Karen Ellis is co-editor of the Journal IDA along with Dr. Sarah Herd. Dr. Ellis is a general dentist for the Marion County Public Health Department and can be reached at ellis_karen@yahoo.com.like family and by family who became patients. I always say that even though some of the worst times of my life occurred while a student, so did the best. And, things began to “click.” I learned that the world wasn’t run by geniuses alone but also by those that refused to quit. I refused to quit. I was grateful for the hard times because they made me a better dentist. I knew I wasn’t going to let anything stop me from becoming a dentist. Those years at IUSD were instrumental in shaping my grit and RESILIENCE.

5VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental AssociationBolstered with curiosity and my new found resilience, I moved to St. Louis, Missouri for my General Practice Residency at Washington University School of Medicine. I was now in an environment that was in complete contrast to IUSD. My attending dentists were mentors and actually invested in who I was as a dentist and person. They wanted to see me succeed. The rotations through emergency medicine, anesthesiology, oral surgery and pediatric dentistry were challenging, inspiring and collaborative. My favorite experiences though were working side by side with an attending dentist in the operating room with general anesthetic cases for adult patients with developmental disabilities that prevented them from being seen in our oces. Not only were we doing a service that improved the lives of whom we were treating, but that time one on one with an expert to ask questions, be asked questions and work in partnership have always been the highlights of my professional career. No one had an ego in the OR and the goal was always the same—to give the absolute best care to those who needed us most. The patients may not have realized the benet to what we were doing, and they certainly didn’t know that all of the margins were sealed on a Class II restoration, but I always saw the look of gratitude in the eyes of a parent or loved one when we met with them in recovery. It was then that I knew I wanted to help those that could not help themselves or who needed extra assistance with getting dental care. This began my career in public health dentistry. I also thought of always doing my best even when no one was watching. Those patients under general anesthetic were at their most prone. I appreciated that I was working with those that understood “good enough” was NEVER good enough or acceptable. Even in dicult environments or challenging situations, I learned the importance of INTEGRITY. Always do your best.I have been in dentistry for 25 years now, and I am continually shaped by events and experiences that I learn and grow from. I have been a member of organized dentistry for 23 of those 25 years and that has been one of the best decisions I have made. I initially joined to make new friends and because I wanted to have a sense of belonging. In the beginning, I was thinking about what I could “get” from being a member of organized dentistry and not how I could “give.” I was reluctant to get more involved but I was encouraged to join the IDDS Foundation and also the IDA Dental Education and Practice Council. There is great importance in what the tripartite does for its members, the profession and the community. And a funny thing happened, the more I began to serve and give the more I got back in forms of connection and love. Thanks to organized dentistry, I have been able to engage in SERVICE for the greater good and what it means to be a servant leader. As I wrap up my tenure as Co-Editor of the IDA Journal, I wanted to share some of the moments in my life that made me the dentist I am today. What experiences have you had that have shaped your beliefs and made you the professional you are? I would love to hear them. I personally want to thank you for allowing me to share parts of my life in this format and also to SERVE you. It has truly been a privilege.

6 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2Thank you for electing me to be the president of the Indiana Dental Association for the next year. The mission of the IDA is to support dentists, to promote professionalism, and to improve oral health. My goal as President is to continue the mission of the IDA by representing the goals and concerns of the membership to fulll this mission. The leaders before me have modeled this mission well. I would like to recognize the members who have attended the meeting with strollers in tow! These members and their families have made accommodations to remain actively involved while raising their families. This is a testimony to our changing landscape. I commend you for the eort to make this happen and am so excited to see this.A little bit about me. I have been a member of organized dentistry since August of 1983 as an ASDA member when I began dental school at The University of Louisville. I remain an active member in Kentucky, Florida and here in Indiana. But my real engagement started several years ago when I was asked by Dr. Sue Germain to consider applying for the IDA AIR Leadership Program in the 3rd year cohort. The AIR acronym stands for Acceptance, Inclusion and Respect. This program teaches skills needed for leadership. Several of my classmates as well as many other graduates are in this room today. At the completion of that two-year program, I was encouraged by Dr. Dave Holwager to run for trustee of my component, the Ben Hur Dental Society. I did. And I was elected. Then during my time as Ben Hur president, I was encouraged by so many of our members to continue in leadership at the IDA committee level. Once involved for several years and with continued support from many leaders in this organization, I was encouraged by Dr. Tom Blake to go through the line oces for the IDA. The reason I am telling you this story is to ask you to seek out potential leaders in your component dental society. Encourage them like I was encouraged. And when you are on the receiving end of that invitation to get involved… step up and lead. Take advantage of the opportunity to be a leader. Sometimes others see leadership potential in you, even before you see it yourself. Embrace it and take the opportunity to lead.I have a vested interest in leadership, as I have served on the IDA Leadership Committee for several years, most recently as chair. During my time as chair, we encountered a milestone. Several years ago, this House adopted a new committee and subcommittee structure that included three two year term limits. This year, for the rst time, many longtime volunteers termed out of their committee positions. Several of them were committee chairs. We saw the number of vacant slots and began the plan to ll them. We issued a call to current leaders, especially trustees, component presidents and component executive directors to help us and they came through. If you look at the Leadership Committee’s annual report in your House Manual, you will see that almost all of the volunteer positions have been lled. Thank you all who submitted names for committee member prospects. Thank you to those of you who said “yes” and stepped up. We are in good shape.One of our Strategic Plan goals is to make ecient use of volunteers. Thus, rst, we are going to make volunteer recruitment an Dr. Lisa Conard, 2024-25 IDA PresidentPRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Inaugural Address of Dr. Lisa Conard, 2024-25 IDA PresidentON MAY 18, at the 2024 Second House of Delegates, Dr. Lisa Conard became the 2024-25 IDA President. A general dentist in Lebanon and adjunct professor in Cariology and Operative Dentistry at IUSD, Dr. Conard gave the following address to those in attendance.

7VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Associationongoing process. While we usually know in advance when our IDA volunteer opportunities are going to happen, we often nd out about ADA leadership opportunities with very little notice. We want to be prepared by having a pipeline of prospective leaders on standby. The IDA sta is in the process of a revamp of the IDA website. It will include a volunteer site where any member can review upcoming opportunities and express an interest in getting involved as a committee or subcommittee member or consultant. If you have diculty nding this option, please email myself and Andrea New, IDA’s director of volunteer engagement, so that we can get you involved.Attending continuing education meetings usually ignites enthusiasm from presentations in materials, technology, practice management, etc. Those of us who attend the House of Delegates are also intrigued and often inspired by the issues brought before this House, as well as in private discussions and concerns that are shared in casual conversations. My hope is that those of you that have had ideas and thoughts will apply for positions on committees by going to the IDA website and signing up to be committee members so that we can tap your skills and thoughts. Second, we want to equip volunteers with the skills they need to be successful. When Dr. Tom Blake surveyed committee chairs last year, one of the things they asked for was additional training. Again, as an AIR graduate, I know how important training is to help you build your skills and condence as a leader. We are going to have a leadership workshop this year that will provide committee chairs and trustees with guidelines and outlines to help them eectively run meetings. We are going to help them develop clear expectations and an understanding of the purpose of each position. I believe in clear outlines of these positions to encourage people to volunteer knowing the expectations and feeling that they have support to accomplish the goals. Andrea New is going help me develop ocer and committee “manuals” to assist with record keeping and to help leader transitions go smoothly. We will hold a trustee and committee chair (along with their sta member) leadership session, complete with templates for meeting agendas, minutes and nancial recording. This formalization will help with record keeping so that information is easily available for future reference. Having this training can help meetings be more organized and productive, thereby respecting volunteer time.Third, we are going to support volunteers by making better use of technology. The IDA has been through a major technology update and the new website will be unveiled before the end of the year. Plus, the ADA will launch its new association management system this summer. Each of these upgrades will assist chairs and their committees with organization and eciency. These are all exciting opportunities to continue with our existing foundation while laying a new foundation engaging the creative minds of our new committee members who will produce an even more vibrant association. We have recently made great strides legislatively and our relationship with the school is strong. With the recent emphasis of mental health wellbeing, we are addressing having assistance for our members overall health with great strides and initiatives through our newly formed Be Well Subcommittee. Two years ago the need for mental health assistance is our profession became much more apparent to us. IDA leaders formed a subcommittee and entitled it Be Well. This committee is providing resources for health, lling in between stress and addiction. Our Be Well subcommittee is making great strides, holding multiple sessions at this MDA that were highly attended. We are serving the needs of our members. Thank you to all who serve on this subcommittee.During the next year we’re going to have to closely examine our nances and make sure we make the best possible use of every dues dollar. We will examine every IDA program. This examination will allow us to determine which programs that are successful and benecial to our membership, and programs that are not. I have begun to put together a task force that will evaluate our budget line item by line item considering expenditures and value to our overall association. We will ask each committee chair for information to assist with gathering this information. It will be compiled by August 1 so that we can present ndings at the leadership training and the September Board meeting.While we face these changes, I see opportunity. In 2026, Indiana will be hosting the ADA Annual Session – SmileCon for the rst time ever. This October we hope to help elect our own Chad Leighty as President-Elect of the American Dental Association. If elected this fall, Chad will complete his year as ADA president right here in Indiana at the 2026 SmileCon. We are looking forward to that!During the past three years as I’ve moved through the chairs of leadership, I have learned a lot but undoubtedly, I have much still to learn. I ask that you please do not hesitate to share information that you may have that could help as well as sharing your concerns. I want to hear from members as I believe that your leadership is here to serve you. Thank you so much. We are stronger together.

8 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2PAST PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE A Year in the Life of an IDA President… A Look in the Rearview MirrorI AM SURE that by the time that many of you read this that I will have become the Immediate Past President after the Midwest Dental Assembly which was held in French Lick. This has certainly been a time of personal reection and has given me time to look retrospectively at my almost 43-year career (which I have cherished…MOST of the time).I believe that there are so many transitions in our lives and nishing my year as YOUR IDA President is just one more milestone to celebrate. But I am getting ahead of myself. While I have always been a member of Isaac Knapp since graduation, I have not always been involved as a leader in organized dentistry. Knowing that 18 years y by so quickly, I spent my rst 15 years involved in my kids’ schools. I, like so many dentists in my era, have not worked with patients on Fridays unless it was volunteering at Fort Wayne’s Matthew 25 charity clinic or doing some other volunteer work. Going into schools on Fridays to help was simply a joy for me to be around all of those young eager minds and I loved planning activities with the school administration to make education an enjoyable experience for the students. Of course, 12 years of pre-college education is over before you know it and then my sons headed to college. It was at this transition that I had promised my own dentist and mentor, Dr. Gerry Kaufman that I would become involved in Isaac Knapp, which I did for several years on the board and eventually went through the chairs to president in 2011-12. Unfortunately for me, Dr. Kaufman passed before I assumed the oce. I am sure that he knew, however. I have been more than blessed to be a member of such a vibrant local component. I am glad that many senior members of IKDDS saw the leader in me back when I rst started out my organized dentistry career. That mentorship and encouragement along the way helped me to erase some of the PTSD from dental school. (I’m sure we can all relate.) My time leading Isaac Knapp was very rewarding even though during my presidential year I did not have an Executive Director to do the things that Jamee Lock does for Isaac Knapp now. As I reected back to my beginnings, I realized how important it was to have relationships with same-aged peers and started our Young Dentist Committee which has provided most all of the ocers of Isaac Knapp in the last several years. I am a sucker for the younger dentist. I continue this mission to this day serving as the group’s mentor. My desire for these young clinicians is for them to love our profession at the twilight of their careers as much as I do. I understand that each person has his or her own personal journey in the work/life balance arena and MUCH has changed in the last four decades. It has ALWAYS been my goal to assist students and young graduates in our eld. I hope in some respect that I have been of assistance along the way. This by itself would be a wonderful legacy to leave our profession.Of course, in my later years of my practice life, a monumental transition for me was “coming out” at such an advanced age. It wasn’t easy by any stretch of the imagination and I was worried that I would lose the respect of friends, family and colleagues, but one of my foundational words in my leadership language has always been transparency. How could I truly be transparent if I was living non-transparently in this aspect of my life. Coming to meetings at rst was dicult but I was determined to give my best in serving as both an Alternate Delegate and the Delegate to the Annual IDA Meeting (now MDA). To my delight/relief my friends rallied around me as I was still the same Tom Blake…now just living my truth. It was an absolutely amazing time of my life. I am guessing that people still saw the leadership qualities in me and respected my leadership style as many encouraged me along the way. I had always been the Treasurer Dr. Tom BlakeABOUT THE AUTHORDr. Tom Blake is a dentist in Fort Wayne and the 2023-2024 IDA president. He can be reached at tblake5591@aol.com.

9VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Associationof EVERY organization that I was a part of whether it was the PTA, Athletic Boosters or our neighborhood pool board. Numbers are “my thing.” I served as a member of the IDA Finance Committee for many years and when it was known that Dr. Dan Fridh was going to step down as Treasurer, I was encouraged by friends (especially Dr. Steve Ellinwood) to apply for the position and lo and behold, I served in that position for four years…yet ANOTHER transition. It was NEVER on my radar screen to become the President of the IDA and since it is usually a trustee who moves in to go through the chairs, I really didn’t even think about it at all and then something happened. Some of the younger members of the IDA encouraged me to run (among them my good friends Drs. Matt Kolkman, Caroline Derrow, Mandy Miller and Megan Keck). I really had to think about it for a couple of weeks and honestly didn’t know what the process was to run. So, I called Doug Bush. I know that it was a shock to him to be entering the race in February right before the unknown shut down of the world from COVID. So many thoughts raced through my head. Can I do this? Do I have the time? Do I have all the knowledge I need? Will my lifestyle be something that will determine the results? On and on…I nally decided that indeed I would give it a shot AND it was a contested election. I tried to tell myself at the time that no matter how the results ended up that I would be ne, but then I REALLY wanted to win. I felt I had a good platform and lots of support from so many delegates and ocers. Fast forward, past three re-votes due to technical errors since the meeting was on Zoom and I WON! Next transition.So here we are four years later and I couldn’t be happier or prouder that I decided to take the call to head our organization. It has been an amazing four years leading up to this honor and I thank each and every one of you for what you have done to make our organization stronger. Whether it be encouragement, advice, or just a kind text or voicemail, you have meant the world to me. So many experiences I would never have had have now been a realization. I have met state presidents from across the U.S. I have learned so much more about advocacy. I actually got to speak at last year’s IUSD graduation with the current ADA President- Elect. I have gotten to see rsthand how respected Indiana is on a national level. I have seen the inuence that Doug Bush has with other executive directors. I have gotten to give so many speeches for so many dierent events that I never would have gotten to had it not been for those who urged me along the way. It truly has been my pleasure and such an honor and so THANK YOU all.We have had an excellent year this year thanks to YOU and your involvement. Our new programming of the monthly FrIDAy with the IUSD students has been so successful and will continue to level the speed bump between school and rst practice experiences. Welcoming our young colleagues is crucial to the vitality of our organization. Our new Ten Under Twenty group has been formed and we are busy incorporating these leaders into the IDA structure. Our Government Aairs Committee led by Director of Government Aairs Shane Springer hit multiple home runs this year with the passage of Assignment of Benets and Network Leasing will be of great benet to all dentists AND patients in the future. (taking eect July 1, 2024) This would not have happened without YOU contacting your legislators. I am proud of what we have done and look forward to a successful future transition.So as I transition to my new job as Immediate Past President, I anticipate future victories for us. Our Executive Committee is strong and has great ideas as the landscape of organized dentistry is going through great changes. We have the right people in place. For better or for worse, you are not getting rid of me quite yet either. As I have transitioned to semi-retired as “Two Day Tom,” I intend to assume any role which may need attention according to our new leadership group. I am here for all of you and for our outstanding organization. We are dynamic, versatile, thoughtful and nimble. We will continue our role as a leading state in the ADA. Thank you again for an amazing opportunity to serve you. I will treasure this experience forever.

10 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2In 1901, Dr. Frederick McKay left his practice on the East Coast and relocated to Colorado Springs, Colorado, where he encountered a dental condition that he could not explain. Many of his patients had brown stains on their teeth. The locals had theories about what caused the condition, none of which Dr. McKay could nd in any dental literature of the day. With the support of the local dental community, they conducted their own study and found that almost 90 percent of local children showed evidence of the odd condition that came to be known as “Colorado Brown Stain.”In 1909, Dr. McKay persuaded renowned dental researcher, Dr. G. V. Black, to visit Colorado Springs to collaborate on the condition. While rst skeptical that a new dental disorder had been discovered, Dr. Black later wrote: “I spent considerable time walking on the streets, noticing the children in their play, attracting their attention and talking with them about their game, etc., for the purpose of studying the general eect of the disorder. I found it prominent in every group of children…. This was much more than a deformity of childhood. If it were only that, it would be of less consequence, but it is a deformity for life.”1Drs. McKay and Black noted that children with the staining showed remarkable resistance to tooth decay. They continued to investigate the condition, with little success before Dr. Black passed away in 1915. Dr. McKay suspected the condition related to the local water supply but could nd no proof until he was called to Oakley, Idaho, in 1923. Local parents there described the same tooth stain he had seen in Colorado Springs. Oakley’s water was supplied by a single spring not far from the town. Dr. McKay persuaded town leaders to abandon the spring for another water source and within a few years, the stains stopped appearing. He felt the water supply was the culprit, but testing didn’t indicate anything out of the ordinary about the water in Colorado Springs or Oakley. In 1931, when the Aluminum Company of America (Aloca) used new, more sensitive photospectrographic testing equipment, they identied an unusually high concentration of naturally occurring uoride. The mystery cause of the mottled brown teeth was nally solved.Dr. H. Trendley Dean, head of dental hygiene, and chemist Dr. Elias Elvove, both of the National Institute of Health (NIH), began searching for a uoride sweet spot… a concentration of uoride that preserved tooth strengthening properties, while eliminating the mottling eect. The rst large scale test of uoride supplementation occurred in 1944 when the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan, voted to add uoride to its public drinking water supply. During the 15-year study, researchers closely monitored the tooth decay rate of 30,000 school aged children. After just 11 years, the caries rate among Grand Rapids chil-dren had dropped by 60 percent. For the rst time, dental disease could be considered highly preventable.Mr. Doug Bush, IDA Executive DirectorEXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S MESSAGE Fluoride: History and FutureFEW DENTISTS WOULD dispute the benets of uoride in drinking water, but some may not be familiar with the history of community water uoridation and how it came to be. As has been the case with many discoveries, the benets of uoride were found by accident. ABOUT THE AUTHORMr. Doug Bush is serving his 28th year as IDA Executive Director. He can be reached at doug@indental.org. Eighty years have passed since Grand Rapids introduced community water uoridation. As of 2018, the ADA reports that 74 percent of the U.S. population is served by water districts providing optimal uorida-tion.2Of course, community water uoridation has had detractors since it was rst introduced. Some opposition has been political: “Should the gov-ernment be involved in imposing uoride on the public?” That sentiment

11VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Associationfound its way into the cold-war cult classic movie paro-dy, “Dr. Strangelove” (1965). Noting that uoridation was introduced immediately after World War II, General Ripper concludes uoridation was clearly a “post-war Commie conspiracy” to poison drinking water. His logic was hard to refute. “Have you ever seen a Commie drink a glass of wa-ter?” he asks. “Vodka. That’s what they drink. Never water.” Other opponents of uoridation are more serious. The Fluoride Action Network (FAN) declares that their mission is, “…protecting public health by ending water uoridation and other involuntary exposures to uoride.” They pledge to, “Protect public health in communities experiencing high levels of uoride in water due to pollution or natural occur-rence.”3The group is zealous and, in some cases, eective. In fact, a number of Indiana towns have discontinued, or are considered discontinuing, community water uoridation, partially as a result of FAN inuence. According to Jim Powers, manager of the Indiana Depart-ment of Health’s Water Fluoridation Program, the Indiana communities of Goshen, New Castle, Jasonville and Bristol have announced that they are, or are considering, discon-tinuation of community water uoridation. In some cases, decisions are being driven by the cost of replacing or re-pairing aging equipment, but in other instances, decisions are being driven by vocal anti-uoridation activists. NBC News recently reported an increase in the number of communities around the country discontinuing uoridation, based on misleading claims and perceived government oversteps. They speculate a new surge in anti-uoride sen-timent is fueled by pandemic-related distrust of the govern-ment and healthcare authorities. According to Mr. Powers, support from the dental community has historically been critical to keeping community water uoride systems op-erating. Town leaders pay more attention to local dentists than national experts. “I am grateful for any help the IDA and local dentists can provide,” said Mr. Powers. The IDA is currently working with the Indiana Department of Health to craft legislation that would require local commu-nities to notify the Department of Health before discontin-uing uoridation. Too often, the dental community learns about the discontinuation of uoridation after the decision has been made. Even without such a notication require-ment, it is important for local dentists to remain engaged on the community uoridation issue. Meet your mayor and get to know members of your city or town council. Oer yourself as a resource any time they have questions about an oral health issue. Take advantage of excellent resources on oral health and the benets of community water uori-dation, available from the American Dental Association. And don’t forget to talk to your patients.Dr. Donald Chi, a pediatric dentist at Seattle Children’s Hospital, explained that he had to rethink how he talks to parents who are concerned about uoride. He noted the conversation starts not with data, but with empathy.“There’s a lot of disinformation out there that preys on the vulnerability of patients,” said Dr. Chi. “People don’t want information. They just want to talk through it and process it.”4Sources1. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, “The Story of Fluoridation”. See www.nidcr.nih.gov/health-info/uoride/the-story-of-uoridation2. American Dental Association, “Fluoride Facts” See www.ada.org/resources/community-initiatives/uoride-in-water.3. Fluoride Action Network. See www.uoridealert.org 4. NBC News, “Medical freedom vs. public health: Should uoride be in our drinking water?” See https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/uoride-safe-drinking-water-cities-ban-rcna143605

12 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2COVER STORYFinding My Calling: My Journey to AcademiaI HAVE NEVER been shy about sharing my dental school journey. I share it so often I always assume people know the ins and outs, but I think more often than not a lot of people have no idea how dental school was for me. And knowing how school was for me is key to understanding why I wanted to eventually end up in academia.Dr. Elizabeth SimpsonMy father had been having some health problems leading up to me starting dental school. I attended Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, and two months into starting school he was diagnosed with stage IV renal cell carcinoma and was given four months to live. I ew home to Indianapolis to be with my mom and dad the weekend after we got the diagnosis. I am an only child and my parents and I were very close, so over the course of that weekend, I secretly thought maybe I should leave school or try and transfer to IU to be closer to my family.When I got back to school on Monday, I went to talk to our dean of academic aairs, but on the way to his oce I ran into the dean of the school at that time, Dr. Lonnie Norris, who was the rst African American dean of the dental school. I told him what was going on at home and admitted that I was thinking about leaving school or transferring. He looked me in the eyes and said “No. You will stay here, and we will get you through this.” I felt his sincerity, even with just the few words that he spoke. And so, I stayed, but not without tears. Not without lots of ights home to be with my family at various times. Not without an accidental needle stick from an HIV+ patient and having to take anti-retroviral medications for a month. Not without nishing almost a year late. Not without panic attacks and depression and being prescribed anti-depressants. Not without counseling.Let me tell you, I felt so much support from my friends, faculty and sta that I knew I would nish school. There were times when I felt more from outside inuences that I would nish school than I felt from my own internal motivation. I can’t tell you the number of times I thought, “I hate this place,” school and Boston in general. On top of my dad’s illness, I was the student whose patients consistently didn’t show. I was the one whose procedures would fall through. During my third year, I went to meet with Debbie, the on-campus counselor for the medical and dental school students. I was so embarrassed about having to take medication, but Debbie told me seven out of the top 10 most prescribed medications to the med and dental school students were anti-depressant/anxiety medications. While I was relieved, I was also frustrated because in my mind, that meant that some of my friends must have been taking medications, and no one was saying anything about it to each other. I felt like everyone knew how stressed I was, and they would comfort me, but not share their own struggles. Sometime during those sessions with the counselor, I got the idea that if there was so much unsaid depression and anxiety in the pursuit of the professions that we were so hopeful about, someday I wanted to be a “a dental school counselor” and do for students what I felt like faculty and my counselor did for me. I got the idea, and it never left. I would envision myself in my oce in the dental school, and students coming to me just to talk about what they were going through. And while I would never discount the credentials our counselor had and the help she provided me, I felt that I would be even more of an asset because as a dentist myself, I could relate to what the students were going through. I had walked in their shoes. Thankfully, my father outlived his initial diagnosis by two years. We were lucky that he would go through periods of remission, but ultimately, he lost his battle to cancer three days after I took part II of the NBDE. He passed June 30, and I only had the month of July before summer vacation, so I stayed home with my mom until school started again in the fall. I did y back

13VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Associationto Boston for a couple days that summer. When I got to school, I went straight to one of our operative faculty members, who I am in touch with to this day, and told her the news. She pulled out a chair in her oce, oered me Fiddle Faddle popcorn and we sat and talked.There’s so many more small (but big to me) details of my story that would make this article the length of a novel. But it comes down to I had a bad experience in school and wanted to use my bad experience to pour into other people. I wanted to look out for the people who I thought might be silently struggling. To me, it felt like everyone else was having a grand time in school: having patients who consistently showed, getting their requirements knocked out in a year, meeting their signicant others and getting married. But now, as faculty, talking with students daily, I think there’s a lot of silent suering. I think it’s safe to say most people think that going into academia – particularly clinical full time – is an end-of- career move. We are constantly told we have to keep our hands wet, and while I completely agree, if we continue with that notion, academia will always be an end-of-career move. I think dental schools would benet from more middle career folks who hear the call to academia and accept it. Another reason I wanted to go into academia, and I hope I don’t get “canceled” for this, is I want to help create more dentists like me. I spent the bulk of my years in practice working in Federally Qualied Health Centers serving the underserved. Now that I am at IUSD, I talk to whoever I can, whenever I can, about a career in public health. I would venture to say that dental schools (not just IUSD) are full of clinicians who came from a private practice setting and are able to give plenty of advice about their experience, but very few people do the students have that they can talk to about what a career in public health might look like. The students spend a couple of weeks on their community dentistry rotation, but if there aren’t dentists who worked in centers like that to keep the conversation going, I think the rotation just becomes a fun experience when they got a break from school for a couple weeks. I’ve even talked to students who give wanting to work with the underserved as their motivation to become dentists, only to be swayed by the perceived glamour of private practice. I had a student tell me a couple years ago that one of her classmates said that public health is not “real dentistry.” I have students come talk to me about public health because, as far as they know, they won’t make any money and will live a pauper’s existence. I’ve talked to students who have excellent hand skills and are interested in serving the underserved express hesitation about it because they are told they are “too good” to work in public health. We all realize the importance of having dentists who will serve the underserved, but we don’t have enough people talking positively and from their own experiences to the students about it. So, I am there to talk about it. People often cite the nancial compensation as why they can’t aord to be in academia full time. I would like to gently push back at that and tell you that you can make it work – if you want to. For me, it was worth the pay cut. I did have to sit down and look at my nancials and yes, I had to give up some things, but it was worth it. People always say nd a job you love, and it won’t feel like work. I always thought that was poppycock – until I got to IUSD. The clincher for me came last year. I had recently become one of the clinic directors, and I was chatting with a fourth year student. She said, “being a clinic director is kind of like being a dental school counselor,” and I knew I was where I am supposed to be. I asked my friend and colleagues, Dr. Natalie Lorenzano, who is a full time visiting clinical assistant professor, why she chose a career in academia. “Going into dental academia was more of a calling than a choice. I felt the pull early in dental school that I would want to come back to be a tangible tool to our students and future dentists. It’s important to me to continue to lift up this profession and make sure we are sending competent, holistic and kind people into the eld of dentistry.”Some of you may never hear the call. That’s okay. But some of you may, and you may have it sooner than you think. Don’t feel like you have to have a story fraught with tragedy and frustration like mine to be in academia. Maybe you are one of the people who loved school. I would say come to the school and help create the experiences that made you love it as well. There’s space and need for all of us. About the AuthorDr. Elizabeth Simpson is a Clinical Assistant Professor at IUSD and a clinic director in the Comprehensive Care Clinic. She also serves as chair of the American Dental Association’s Council on Advocacy for Access and Prevention and is an ADA delegate for the Indianapolis District Dental Society.

14 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2A Day in the Life: IUSD Students in Their Own WordsI HAVE BEEN fortunate that in my two years at IUSD, I have gotten to know some wonderful students. I think anyone who works at the school will tell you, getting to know the students is the best part of the job. I asked several students if they would share either a quick outline of a day in their lives or the best and worst parts of dental school in their opinions. I hope that in reading these anecdotes, you will reminisce about your own dental school experience and maybe even become inspired to start working at the school! COVER STORYDr. Elizabeth SimpsonNina Bakshi, D4A day in my life at Indiana University School of Dentistry always starts with saying “hello!” to my fellow classmates, faculty and sta working at the school. After nding where in clinic I will be working, I prepare for my patient to arrive for my morning appointment. One thing I love about learning dentistry alongside all my peers is being able to always cheer on my friends who are also seeing patients at the same time. Watching a friend prepare for a crown delivery in the operatory down the aisle is so exciting! Even though I may be busy with my own patients, I always love that I am somehow a part of my classmates’ initial learning experiences in the eld. After taking lunch, I will return to clinic for my afternoon appointment or work on some of my cases in the laboratory. Working in the laboratory is not my favorite thing to do in dental school, especially for the classes with laboratory components I am taking. I much rather prefer seeing patients and being around people. However, I understand that this is a step in the learning process—and I am grateful for all I have learned! Being a D3 student can be very demanding, but also very rewarding at the same time. Being able to apply all your studying and pre-clinical laboratory work to actual clinical cases makes all the tough times worth it.Dustin Broyles, D4A typical day in the life of a third-year dental student is a rigorous and demanding experience that combines theoretical learning with practical clinical applications. The day begins with lectures covering advanced topics such as prosthodontics, surgical periodontics, and oral surgery. After the morning classes, we transition to the clinic where we engage in hands-on patient care under the supervision of faculty. This involves diagnosing and treating a variety of dental conditions, performing dental procedures, and honing our skills in patient communication and care. The day concludes with studying and preparing for the next day’s clinical responsibilities, creating a well-rounded and immersive educational experience for aspiring dental professionals. Personally, my favorite part of the day is the hands-on clinical experience that we get. Working with real patients allows me to apply the theoretical

15VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental AssociationJordyn Caffray, 2024 graduateMy days during my fourth year tend to vary drastically, but most commonly involve an exciting and educational next step in both a patient’s treatment plan and in my experience at IUSD. During our 3rd year, we have a lot of comprehensive oral exams in order to introduce ourselves to our patients and create holistic treatment plans. While this consumed a majority of my third year, it helped me really understand what comprehensive treatment plans looked like and how dierent doctors had dierent philosophies, when it came to treatment planning. As fourth year rolled around, I started picking up speed and saw myself performing comprehensive exams in half the time it used to take me during my D3 year. As I got faster and more condent, the more cases I was able to take on and more experiences I was able to have. Going into my D4 year, I was able to nally start on some denitive restorations and prostheses, after many months of taking my patients out of the disease control phase. My fourth year diered a lot from my third year, and I was excited to start working on bigger projects like dentures, RPDs, bridges, root canals, and implant crowns. With bigger projects and cases came more responsibility and more “after hours” lab work, but I was excited to start the journey which would eventually help me graduate in May.It’s hard to choose a specic “day” that would represent what my life is like normally because every day is extremely dierent, but I would say most days usually involve seeing two to three patients, depending on if there is “evening clinic” and if the patient doesn’t “no-show” their appointment. Normally one to three appointments per week are dedicated to dierent mandatory “rotations” throughout the specialty clinics like oral surgery clinic, pediatric clinic, screening (new patient intake clinic), or emergency clinic. When we are not in rotations, we are able to see our own patients of record in the Fritts Clinic. Depending on what procedure needs to be completed that day, you and your patient will be assigned a certain chair on a certain oor of the Fritts Clinic. And depending on how soon after you need to get your patient back for their next appointment, sometimes chairs are booked for two to three weeks, so it’s extremely important that I stay on top of my scheduling to ll my appointment slots and nish my patient’s care in a timely manner. Another option we have during the week is to do lab work during one of our appointment slots. I normally reserve these for when patients no-show their appointment or if the clinic chairs are full and I can’t book any patients during that time slot. These lab days are super important because most steps for our prosthodontic experiences need to be checked by prosthodontic faculty/calibrated faculty at least two days before the next appointment with the patient. Preliminary casts, custom trays, master casts, wax rims, wax-try-in arches, dies, RPD frameworks, etc. all need to be checked at least two days before the patient is back for their next visit, so staying organized is extremely important and utilizing the lab work days is helpful for when you have to nd the specic faculty who can “check o” each step that needs to be completed. After my appointments are done for the day, depending on if I have any lab work to complete for school, I’ll normally go home, workout, discuss dierent highs and lows from our day with my roommates (who are also D4 dental students), go over patient cases for the next day, cook dinner, and go to bed. If I do have lab work or if I need to practice for our national board knowledge gained in lectures and provides a sense of accomplishment when I successfully complete procedures. Moreover, the patient interactions hone my communication skills and emphasize the human aspect to practicing dentistry. On the other hand, the sheer volume of information can be overwhelming at times, but I recognize the necessity of balancing academics with clinical practice in order to become a well-rounded dental professional. Overall, the third year of dental school is a rollercoaster of challenges and triumphs, which will help shape me into a more condent and competent dental practitioner.

16 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2COVER STORYexams, then I’ll stay at school until 8 or 9:00, when our labs close for the night.This past year has been challenging, fullling, frustrating, and educational, but it has sculpted me into the provider I am today. Even though we aren’t in classes anymore, like during D1 and D2 years, we still have plenty to focus on and stress about like lab work, national boards, applying to residencies, nding jobs, and guring out what life is going to look like after graduation. These past four years have own by and I’m so grateful for my time at IUSD.Hadi Hachem, 2024 graduateFrom the day I got an acceptance email to a normal Tuesday in dental school, I wake up everyday feeling blessed that this is what I get to do for the rest of my life (besides nals). One of my favorite things about dental school has been the clinic aspect where I get to learn in a hands-on manner and build relationships with faculty and patients I work with. However, if I had to pick a downside to dental school it would be the lack of continuity of care in the clinic. I understand that it’s dicult for schools to be able to set up the same doctor with a student to complete a long case such as denture, but it can be strenuous to both the patient and faculty when dierence of opinions can intervene with the process and elongate it. This does, however, allow me to look forward to when I am able to manage patient cases on my own in the near future.

17VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental AssociationJose Herrera, 2024 graduateWe mostly see patients all day as we are nishing up requirements. At IU, we are able to schedule for two patients per day, with limited evening clinic where we may see up to three. On certain days, we begin with rounds with our clinical director around 8:00 a.m. Here, we go through case studies and present our clinical patient cases for round table discussions. We then see our rst patients around 9:00. Depending on the procedure, we are usually out by 11:30 where we have roughly an hour to an hour and a half lunch period. During this time, on most days we have speakers come to present and they provide lunches for the students. In the afternoon, we are back in clinic seeing our patients! As a D4, there are a lot of competencies and national board exams to be studying or practicing in lab for. On our down time, such as when a patient cancels, we are in the lab practicing on our dentiforms. This is also a time period where we are all seeking jobs, interviewing, applying for residencies, etc. Despite not having many didactic classes, D4 year denitely keeps us busy! The best part of D4 year is the autonomy that we are given. As long as we are seeing our patients and keeping up with requirements and attendance, we are able to freely schedule when we want to! Another great thing about this year is that we aren’t sitting in lectures anymore. On the ip side, the worse part about D4 year is the busy work. By busy work, I mean the random competencies that we have, case presentations, both written and clinical boards, residency applications and interviews, etc. It denitely becomes stressful despite not having didactic exams anymore! With all that being said, this year has truly prepared me for the everyday life of a dentist, and I am excited for graduation! Tasneem Nada, D2My day starts around 7:45 a.m. I wake up, get ready for school and am usually out the door by 8:30 a.m. I also get in my morning prayer before leaving for school. In a perfect world I would wake up earlier to have breakfast, but usually all I can manage is running out the door with a granola bar and a cup of coee. The morning is lled with lectures from 9-12. From 12-1 we have our lunch break, which I usually spend in the campus center with my childhood best friends who are in school on other IU campuses in Indy. 1:00-4:30 is usually spent in lab or lecture, where we work on our given lab projects for the day. Throughout this time, I will leave for a few minutes to pray my afternoon prayer and get in a snack in an attempt to lessen my hangryness. I usually get home around 4:30-5:00, which is when my sister will come over and we will cook together. My sister is in undergrad at IUPUI, which is pretty convenient for us to spend some time together. We eat dinner and I always spend some time facetiming my parents, talking about our days together. I nish up the night by getting in an hour or two of studying, or if it is an exam week, I will usually spend the rest of the night studying. I try to do something enjoyable before going to bed, something like watch a movie or TV show to stay sane. I then get ready for bed and get ready to do it all again tomorrow!

18 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2COVER STORYDarius Warner, D3Mondays encapsulate the essence of our entire week, commencing at 8 a.m. with Dr. Michelle Kirkup’s discourse on xed prosthodontics, concluding at 10 a.m. We then descend to preclinical lab from 10 a.m. to noon, where we meticulously hone our crown prepping skills for upcoming projects and practical examinations. 12 p.m. to 1 p.m. oers a breather or an opportunity for enrichment through club meetings and lunch and learn sessions. Post-lunch unfolds a systematic approach to dentistry from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. in Systems Approach to Biomedical Sciences II (SABS), featuring various esteemed professors. Our day reaches its end, as we immerse ourselves in Clinical Application of Cariology and Operative Dentistry I with Drs. Laura and Willis. Our academic day then concludes at 4 p.m., where we are tasked with the choice of studying for our classes or focusing on our preclinical skills. Often our days really end at 9 p.m.—sometimes later for others. The best thing about dental school is getting the opportunity to learn so many dierent skills that will help to later serve the community we work in. The worst thing about dental school would have to be the early start time. This Monday mosaic mirrors the rhythm and substance of our week—a blend of knowledge, skill renement, and camaraderie to which we thank God for the weekends to come!

19VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Association

20 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2Challenges of Academic Life in Dental Schools: A Faculty Perspective on Connecting All the Pieces to SucceedIN THEIR RECENTLY published article, Burns et al.,1 writing in Oceanography, state that academic science is becoming increasingly recognized for fostering a toxic workplace culture. They list reasons including the presence of a hierarchical academic structure, intense competition among faculty, excessive workload expectations, and lack of adequate nancial compensation model. How does this translate to dental schools?The desire to train and practice dentistry often begins early in the life of a future dentist. When listening to applicants who wish to enroll in dental school and subsequently pursue a career in dentistry, a commonly stated line is ‘I was inspired by my dentist, who I used to go to for treatment when I was younger.’ However, the desire to join the dental faculty on a full-time basis is now a more nuanced and challenging option. The focus of this article is to assess the challenges faced by faculty in dental schools and look at the challenges facing them in their roles as educators.The Number of Dental SchoolsIn 1950, there were 42 dental schools in the U.S., with 60 percent of them being aliated with private universities. The number of schools increased to 60 by 1978. In the mid-1970s, the applicant pool started to decline and by 1989, six of the dental schools were closed. However, by 2013, the number schools increased to 64. Currently, in 2023, there are 72 dental schools in the U.S. and 10 in Canada. The number of applicants to dental schools has shown a signicant increase over the years. In 2007-2008, there were 13,742 applicants to dental school in 56 dental schools.2 Based on recent data, there are approximately 11,000 applicants per year seeking admission to dental schools. According to the American Dental Education Association (ADEA), the average dental school acceptance rate in the US is 53.5 percent.2The Number of Faculty in Dental SchoolsWanchek et al.3 reported in 2017 that a total of 12,926 faculty members who were employed at some point during the 2015–16 academic year at 63 schools participated in their survey. This number was broken down into 5,061 full-time faculty members, 5,814 part-time faculty members, and 2,051 volunteer faculty members. Forty-seven schools that reported had at least one vacant budgeted or lost position. While it is not new, it is worth repeating that dental education is facing a faculty workforce shortage. This has become more acute in the post COVID 19 pandemic phase that we currently occupy. Ramications for the future includes signicant impediments to institutional growth and innovation. Dr. Priya ThomasDr. Monica GibsonDr. Chandni BatraDr. Hawra AlQallafCOVER STORYDr. Neetha SantoshDr. Celine CorneliusDr. Halide NamliDr. Vanchit John

21VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental AssociationIn 2006, ADEA started a program titled, ‘Academic Dental Careers Fellowship Program’ (ADCFP).4 The goal of the program was to engage faculty members by providing them with tools to help them teach and mentor dental students and allied dental students. Additionally, the intent was to help faculty develop their academic careers plans with the goal of being successful as academics. Faculty members were also provided with tools to mentor dental students interested in academic life as a future career. Additionally, in 2006,5 110 faculty members at 10 dierent dental schools were interviewed by dental students who were participating as ADCFP fellows. Sixty-nine (63 percent of the total) of these interviews were reviewed and analyzed. Positively inuencing factors on the quality of the academic work environment and career satisfaction included mentorship and student interaction, opportunities for scholarship, job diversity, intellectual challenge, satisfaction with the nature of academic work, lifestyle/family compatibility, exibility, lifelong learning, professional duty and lab responsibility. Negative factors identied were bureaucracy/administrative burdens and barriers, time commitment, nancial frustration, political frustration, lack of mentorship, required research emphasis, lack of teaching skills development, student engagement, isolation, and funding uncertainty.In 2007, Haden et al.6 reported on the ‘quality of dental faculty work life.’ The study was designed to evaluate faculty perceptions and recommendations related to their work environment, job satisfaction and dissatisfaction, and professional development needs. They had a total 1,748 responses from 49 U.S. dental schools. The total number of respondents constituted 17 percent of all U.S. dental school faculty. Data analysis showed that most faculty members reported being very satised to satised with their dental school overall and with their department as a place to work. However, tenured associate professors reported the highest level of dissatisfaction. In 2011, John et al.7 reported the need for dental schools to develop creative solutions to help recruit, develop, and mentor faculty members. Encouraging dental students to consider academic careers through a ‘grow our own’ plan was discussed among other ideas to help with recruitment and retention of dental faculty. Murdoch-Kinch et al.8 in 2017, in their climate study for faculty, sta and students looked at humanistic environment, learning environment, diversity and inclusion, microaggressions and bullying, and activities and space at the University of Michigan School of Dentistry. Findings indicated that the majority (76 percent faculty, 67 percent sta, 80 percent students) agreed that the environment fostered learning and personal growth and that a humanistic environment was important (97 percent faculty, 95 percent sta, 94 percent students). However, microaggressions or bullying was reported by all groups surveyed. Recommendations made from the ndings included working on cultural sensitivity training, adding courses for interpersonal skills, leadership, and team-building eorts, addressing microaggressions and bullying, creating opportunities for collaboration and increasing diversity of faculty, sta and students.In the ADEA Climate Study9 conducted in 2022, a total of 66 schools (58 U.S. and eight Canadian) participated with responses recorded for faculty, sta, administrators, and students. Sixty-four percent of the participants reported that they agreed or strongly agreed that they were satised with the climate at their dental school. Experiences varied depending upon the participant’s location, role, and social identity group.Based on a brief review of the literature along with feedback from the authors of this article, dental faculty have faced several challenges for many years. Faculty responses to dierent questionnaires over the years have indicated an overall satisfaction with their work and their views on academic life in dental schools. However, the feedback

22 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2responses have also indicated several negatives as well. Dental education has become a more complex enterprise. The rising cost of dental education, increased expectations of students along with increased expectations from faculty combined with more challenging faculty to student ratios has taken its toll on faculty, especially the full-time faculty. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Dental Faculty The global pandemic brought with it signicant changes to life as we know it. Dental education and dental practices had to make changes to continue to provide a safe learning environment for their students and quality care for their patients. Several studies reported on the eects of the pandemic on dental students and sta. However, very few studies have reported on the eects of the pandemic on dental faculty. Smith et al.10 reported on their ndings from dental school faculty from four U.S. dental schools. They self-reported burnout, loneliness and resilience during a one-month period in 2020. Social isolation, new or increased home care responsibilities, and/or nancial hardship along with cancellation of socialization with colleagues at holiday, retirement and welcome celebrations contributed to rates of burnout and loneliness that were higher than the public at large. This added exponentially to the pre-pandemic reported burnout triggers that included academic administrative responsibilities, pursuit of grants and funding, and research. Smith et al.9 also reported that the older respondents, were less likely to report burnout symptoms. These ndings don’t auger well if they are more generalizable as there is currently and is going to be future an increase in retirements of more experienced and seasoned faculty members nationwide. The ndings from the study also indicated, that faculty living alone scored three times higher on the loneliness scale than the group mean. Loneliness was dened as a gap—between the interaction we want to have with others and the interaction we get. As the “graying” of the dental faculty continues, dental schools need to increase their focus on faculty along with providing them with options and support for health and wellness. Arnett et al.,11 in their 2022 study on the Impact of COVID-19 on dental hygiene educators, reported that personal and work-related burnout was signicantly higher for administrator/program directors and full-time faculty compared to part-time didactic and clinical faculty. Emotional exhaustion from personal burnout was positively related to work-related and burnout working with students. Other factors included work-life imbalances, a lack of support, and a shift to hybrid/online learning. Based on the dearth of studies relating to the eects of the pandemic especially in the current post pandemic phase, more work is needed in understanding faculty perceptions of academic life. Ramications going forward will be more critical as there are more dental schools in 2023-2024 compared to prior decades. This combined with increased enrollment of students, will increase the challenges for faculty and their decision to choose a career as a dental educator. Where We Are in 2024As the cost of dental education has increased exponentially, it has become more challenging for young dentists to consider a full-time career in dental education. Graduating dentists usually have a substantial debt load that they need to deal with while trying to establish their careers. Remuneration of the faculty combined with tight budgets of dental schools has made a full-time academic career a distant choice for most dentists. For schools, nding qualied educators who are willing to teach while taking on COVER STORY

23VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2 | Journal of the Indiana Dental Associationthe complexities of becoming full-time educators has become a big challenge. The process of becoming a dental educator is a slow and deliberate journey. Learning to teach requires training. There are many learning options provided by the American Dental Educators Association (ADEA). However, nding time to attend these training sessions combined with the costs of travel and lodging often in locations away from one’s home base means nancial challenges are always going to be present. Finally, with the increase in the dierent and new forms of available technology, faculty must train and retrain to keep up with all these innovations. This is not always exciting to the older faculty, who may choose not to retrain or are not comfortable learning more about new technological options. This can increase tension among faculty and administrators leading to discontent. Learning to become a dental educator while keeping up with new forms of technology, along with dealing with the stresses of working with students and their expectations has increased the challenges that academicians face today. In reviewing the literature, the problems faced by full-time academics is not new. The challenges have persisted through the decades and have become more urgent in 2024. Opening more dental schools, increasing student enrollment in existing dental schools while dealing with the ramications of the pandemic on educators has made of the issue of faculty recruitment and retention more challenging. Dental administrators and other decision makers will need to have a blueprint going forward in 2024 and beyond to ensure that dental students get the best education possible, patients get the best treatment options for their care, while faculty and sta issues are addressed as eectively as they can be. Perhaps dental education is at the crossroads again. In 2024, the need to nd solutions to get the beyond the crossroads is going to be paramount.References1. Burns JHR, Kapono CA, Pascoe KH, Kane HH. Spotlight-The Culture of Science in Academia Is Overdue for Change. Oceanography, 2024, Vol 36 (4).2. Wancheck T, Cook BJ, Valachovic R. U.S. Dental School Applicants and Enrollees, 2016 Entering Class. J Dent Educ, Vol 81 (11) 2017, 1373-1382.3. Wancheck T, Cook BJ, Slapar F, Valachovic RW. Dental Schools Vacant Budgeted Faculty Positions, Academic Year 2015-16 J Dent Educ, 2017, Vol 81 (8), 1033-1043.4. ADEA Academic Dental Careers Fellowship Program (ADEA, ADCFP) https://www.adea.org/dentalfellow/ 5. Roger JM, Wehmeyer MH, Matthews S et al.. Reections on Academic Careers by Current Dental School Faculty. J Dent Educ, 2008, Volume 72, (4), 448-457.6. Haden NK, Hendricson W, Ranney RR et al.. The Quality of Dental Faculty Work-Life: Report on the 2007 Dental School Faculty Work Environment Survey. J Dent Educ, 2008, Vol 72(5), 514-531.7. John V, Papageorge M, Jahangiri L et al.. Recruitment, Development, and Retention of Dental Faculty in a Changing Environment. J Dent Educ, 2011, Vol 75(1), 82-89.8. Murdoch-Kinch CA, Du RE, Ramaswamy V et al.. Climate Study of the Learning Environment for Faculty, Sta, and Students at a U.S. Dental School: Foundation for Culture Change. J Dent Educ, 2017, Vol 81 (10), 1153-1163.9. ADEA Climate Study- https://www.adea.org/climatestudy/ 10. Smith CS, Kennedy E, Quick K et al.. Dental faculty well-being amid COVID-19 in fall 2020: A multi-site measure of burnout, loneliness, and resilience. J Dent Educ, 2022, Vol 86(4), 406-415.11. Arnett MC, Ramaswamy V, Exan MD, Rulli D. J Dent Educ, 2022, Vol86(7), 781-791.See page 35 for author information

24 Journal of the Indiana Dental Association | VOLUME 103 · 2024 · ISSUE 2The State of Dental Curricula: Are We Preparing Students for Today’s Practice and Academic Life?DENTAL EDUCATION APPEARS to have arrived at another crossroads. The challenges laid out in the 1995 publication, Dental Education at the Crossroads,1 persists with the addition of many more in 2024. The challenge of attracting high caliber educators has become more intense over the past several decades. This has been magnied by economics, namely the high cost of dental education, leaving graduates with high debt. This has signicantly reduced the number of candidates applying for full-time faculty positions. The lucrative, albeit stressful nature of dental practice has seen fewer and fewer graduates considering a full-time career in dental education.Additionally, the greying of dental educators and subsequent retirement of the more seasoned faculty that is taking place, is putting considerable stress on the younger dental faculty due to a signicant increase in the demands on their time setting the stage for academic burnout. The global pandemic that was COVID-19 and the subsequent challenges that were faced by dental school globally, has put another crimp in the quality of full-time faculty life. Doing more with less, is not an ideal situation in dental education which is a very hands-on task. This article looks at dental curricula and the challenges faced in implementing a contemporary curriculum in dental schools. A Brief Look at the History of Curricular DevelopmentA curriculum has been dened as the subjects comprising a course of study in a school or college. While the origins of dental education may lie in the works of the ancient Middle Eastern and Asian writers who recorded explanations, descriptions, and advice, about oral health problems, formal or institutional dental education began in the United States in 1840 when the state of Maryland chartered the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery. The nineteenth century saw debate on locating dental schools and dental education within a medical school or in independent schools. Between 1865 and 1870, ve new dental schools were founded. By 1884, 12 additional schools had been founded: Nine university-based programs and three freestanding schools. During the 1880s and 1890s, several freestanding for-prot schools were founded in the United States. The state of Illinois led the way, where between 1883 and 1902, 28 dental schools were started. By 1900, there were 57 dental schools in the country. However, as noted by William J Gies, “Some of the dental schools of this period were busy diploma mills, which were created under the sanction of indierent state laws, conducted with the collusion of unworthy dentists, and protected by unfaithful practitioners in posts of public responsibility, freely sold the degree of Doctor of Dental Surgery at home and abroad, and led to the disgrace of the profession and to the dishonor of dental education. Many of the dental schools that were chartered since 1884 have been completely worthless.”1 Abraham Flexner’s 1910 study of medical education was a landmark event. The Flexner report2 still helps guide medical—and dental—school curricula all these years later. In 1926, the Gies Report3 on Dental Education was published, which was a seminal event for the history of formal dental education in the U.S. Dr. Chandni BatraDr. Celine CorneliusDr. Monica GibsonDr. Hawra AlQallafCOVER STORYDr. Priya ThomasDr. Halide NamliDr. Neetha SantoshDr. Vanchit John