Return to flip book view

Midwest Zen Issue 1 | December 2021 A publication of Great Wind Zendo Danville, Indiana

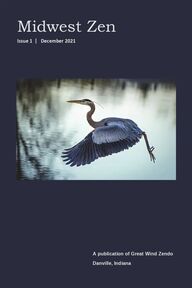

Published 2021 by Great Wind Zendo Editor: Kristin Roahrig Midwestzen@greatwindzendo.org The digital version of this publication can be downloaded at no cost from our website at greatwindzendo.org/MidwestZen. The works included and the opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors, who are solely responsible for their contents. They do not necessarily reflect the opinions and positions of Great Wind Zendo. Midwest Zen © 2021 by Great Wind Zendo. All rights revert to the au-thor upon publication. Address all correspondence to: Midwest Zen Great Wind Zendo 52 W Broadway Street Danville, Indiana 46122-1718 www.greatwindzendo.org/MidwestZen Printed in U.S.A. Cover photograph was provided compliments of Jay Tule. He photographed the heron at Eagle Creek Park in Indianapolis. You can view more of his images at hps://www.jaytulephotography.com/

Page 1 Message from the Editor Welcome to this first issue of Midwest Zen, a venue for Zen practitioners to contribute writings and artforms to express and reflect aspects and experiences on their path. It will enable those who share similar interests to read various perspectives on Zen Buddhism and see the role it plays in their lives. The practice of zazen and the art of writing share certain simi-larities. Zazen can be a way of observation, an aid to release oneself from delusion of separation. Writing and other forms of art share this aspect of the practice of observation. Zazen can be a collaborative partner in writing. Both can be a means to let go of thought and the self, and enable one to be in the present moment. To get out of the way of ourselves, in other words, and in the craft of writing, enable the true self to communicate. This first issue coincides with the anniversary of the opening of Great Wind Zendo seven years ago. It features works from members of the Great Wind sangha and others who have con-nected with the zendo. And now, this issue presents works that will, as described in our statement, provide for both the writer and reader a “still place to explore living with the teachings.” Kristin Roahrig Editor, Midwest Zen Message from Great Wind Zendo I am pleased and excited to see this first issue of Midwest Zen. My hope is that it becomes a platform for exploring life through a lens of Zen practice. It’s not yet clear how the “Midwest” as-pect will reveal itself. While Zen is Zen, it moves and resides in individuals individually. It contains a mix of our beliefs, cus-toms, delusions, and actions and invites us to let them all go. That journey is unique for each person. Midwest Zen will reflect experiences and observations for a variety of people, mostly from the Midwest, and so “Midwest” will inevitably be baked into the pie. Please enjoy this issue and share it freely. Mark Howell

Page 2 Contents ESSAYS 26 Mark Howell Your Day Changes, Mind to Mind 8 Hoko Karnegis Love and Cheerfulness 4 Neil Schmitzer- Can we touch the heart of reality? Torbert 22 Brad Uebinger Self-Care in the Era of Covid-19 POETRY 13 Kristin Roahrig Each Week 19 Kristin Roahrig Glance to Reality 28 Kristin Roahrig Single Grain 12 Lisa Summers During 20 Lisa Summers House Sitting 15 Lisa Summers Landing Rusted Silos Hendricks County, Indiana

Page 3 TRANSCRIBED INTERVIEW 16 Mark Howell The Lure of the Midwest – A Transcription of Michael Komyo Melfi's interview of Shohaku Okumura Roshi ART 25 Loren Malloy Mandala PHOTOGRAPHY Cover Jay Tuttle Blue Heron 2 Mark Howell Rusted Silos 7 Mark Howell Spiral Staircase 32 Mark Howell Center Family Dwelling 11 Sabine Karner Mossy Bricks 14 Sabine Karner Frosted Leaves 29 Sabine Karner Snow Covered Bridge CONTRIBUTOR BIOS begin on page 30

Page 4 Can we touch the heart of reality? When I was younger, questions about life and reality led me to study Zen, and also to study philosophy and to a career as a neuroscientist. Why are we here? What is this life we find our-selves in? What really happens to us in death? These were ques-tions that animated my interest, and at other times, my anxie-ties. Through study and practice, I feel that I’ve learned some-thing about the structure of our experience. The sciences have helped me learn more about how the world works, and how our own subjective experience depends on our brains. And, my practice has been critical for how I understand myself. Some of the anxieties I had as a child and a young adult – about the purpose of life, about my own mortality – do not bother me in the ways that they did back then, and for that I am most grate-ful for my Zen practice. There have been some questions, though, that I feel I have not been able to answer so much as had to give up on, or let go of. Why does this world exist? Why does any world at all exist? These in particular were ones that I struggled with, and it has been difficult to accept that they cannot really be answered. Not through my practice, and not through scientific study. Why does anything exist? Fundamentally, every explanation about reality struggles with the question of existence, as each answer we offer takes existence itself for granted. The very exist-ence of existence, the fact that we find ourselves living this life, is mysterious. In that sense, the heart of reality is a mystery, something unknown and unknowable. In science, we can trace the life of the universe back to its ear-liest moments1 with reasonably high confidence, and there are many strong theories about how the universe came into exist-ence. However, we cannot answer the more basic question of why was the universe able to come into existence in the first place. Why was it possible for something, anything to be? At this point, science has no good answers: each one just pushes the question back a bit further, deferred. And, to be fair, science is not alone here: we should have similar concerns about religious Neil Schmitzer-Torbert

Page 5 explanations that invoke divine intervention – if the world was a product of divine intervention, we still have to answer, why was there a God (or gods) in the first place? William James captured the key difficulty of this question, as he weighed the various approaches people have used to grapple with the question of being (existence): Not only that anything should be, but that this very thing should be, is mysterious! Philosophy stares, but brings no reasoned solution, for from nothing to being there is no logical bridge.2 This line has stuck with me over the years: “From nothing to being there is no logical bridge.” In the end, the question of exist-ence is a firm bedrock that patiently tolerates our efforts to turn it over, and examine it. Frictionless, it effortlessly dodges any attempt to grasp it. Each effort to break through leaves the foundation unmarred, unmoved. While this kind of puzzle is what brought me to study Zen and animated my interest in science, I really do not feel any longer that I’m trying to answer this specific question. I am not looking for a “truth” about reality that will dissolve this mystery. The heart of reality is perhaps something we can feel, or approach the edges of, in our practice. It may be that mystical states (a perception that we experience oneness with existence, or a re-laxation of our individual ego) can help us appreciate that un-known. But, I don't believe there is any possible way for us to perceive the source of existence, whether through science or Zen practice. At the same time, this question is one that I do keep in mind in my practice, as kind of an informal koan (appropriate for someone such as myself, who has avoided formal koan study). Personally, I have found that appreciating the mystery of exist-ence is an important part of my own meditation practice. To find a point at which my efforts to explain the world are able to relax and be still. Recently, I came back to this quote from Carl Sagan that reso-nates with my own attitude today: Neil Schmitzer-Torbert

Page 6 For myself, I like a universe that includes much that is unknown and, at the same time, much that is knowable. A universe in which everything is known would be static and dull … A universe that is unknowable is no fit place for a thinking being.3 Here, when Sagan writes about what is unknown, he was not really referring to that which we can never know. Rather, he is pointing to the work that is left to do for science (that part of experience that can be explained using scientific theories). But, I would also say that it applies here as well. There is much of this life that is knowable, dependable. And, there is something important about understanding that some parts of experience are fundamentally unknowable. To experience the unknowable directly, to reach out and touch the mysterious, is equal parts humbling and wonderful. 1. National Geographic, Origins of the Universe, Explained https:/www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/origins-of-the-universe 2. William James, The Problem of Being, in Great Essays in Sci-ence (1994), edited by Martin Gardner 3. Carl Sagan, Can We Know the Universe? Reflections on a Grain of Salt (1994), in the “Great Essays in Science” collec-tion. Neil Schmitzer-Torbert

Page 7 Mark Howell Spiral Staircase Trustees’ Office, Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

Page 8 Love and Cheerfulness In Dogen Zenji’s Shobogenzo, there is a chapter called “108 Gates of Dharma Illumination.” It’s mostly a long quote from another text called the Sutra of Collected Past Deeds of the Bud-dha. The fourth gate is: LOVE AND CHEERFULNESS ARE A GATE OF DHARMA ILLUMINATION; FOR THEY MAKE THE MIND PURE. Another way to translate the character for “cheerfulness” is a feeling of ease. The character 樂 indicates comfort and ease when it’s pronounced raku, and fun or enjoyment when it’s pro-nounced tanoshii. Of course, when we’re having a good time we’re at ease, so it’s plain to see how these meanings fit togeth-er. However, perhaps we don’t often consider feelings of love, good cheer and comfort to be gateways to the dharma. They may feel a bit like our personal reward for a job well done, a life well lived, and practice goals realized—something to be attained as an end in itself. How is a loving feeling of ease related to purify-ing the mind? A gate is a connection between one place, time or thing and another. It isn’t that ease leads to a purified mind or that a pu-rified mind leads to ease. They arise together at the moment that we free ourselves from mental defilement and see clearly that this moment is all there is. There is no before and after, or movement from one place through a gate to another place. At the moment of awakening we can see that there is no basis for unease or stress, for anger or hatred, or for being joyless and pessimistic. Love, ease and good cheer are our natural state when we stop comparing reality with our ideas and stories about reality. After all, the basic recipe for suffering is wanting things to be other than they are. Putting that energy into help-Hoko Karnegis

Page 9 ing others is wholesome. Putting that energy into being dissat-isfied with ourselves might not be. Sitting in zazen, relaxing our grip on the self and letting the self relax its grip on us, realizing that we sit prior to separation into past and future, here and there, we can directly experience the warmth that arises by itself. Dogen famously wrote in his Fukanzazengi, “The zazen I speak of is not meditation practice. It is simply the dharma gate of joyful ease, the practice-realization of totally culminated enlightenment.” This dharma gate of joyful ease springs up in front of us when we experience and understand reality without our usual delusions and illu-sions that cause us to become fearful, tense or somber. That being as it may, the human condition is such that when a loved one dies, the pink slip arrives or the dishwasher overflows all over the floor, we usually feel anything but tranquil and up-beat. The dharma gate of love and cheerfulness does not ask us to suppress our grief, fear and exasperation, covering it up and denying its existence by simply putting on a happy face. When these feelings arise, we have to enter into them fully, under-stand them completely, and see through them. It may take time—a lot of time—and that work can’t be rushed. However, coming out the other side to some insight into the truth that we create our lives and our world moment by moment can help us settle into the here and now without regret. Can we fully enjoy this moment right now? The past has gone and the future has not yet come. Certainly, our karmic past has shaped this moment, but we can’t reach back and change anything. We can only act now; this is the only position from which we can work. Clinging to regrets about the past or appre-hensions about the future can lead to dissatisfaction with the present because we can’t see and appreciate it in its entirety. The work of love and cheerfulness is not that of becoming a Pollyanna, talking ourselves out of our suffering. Playing the “Glad Game” can make us feel a bit better for awhile, but liber-ating ourselves from delusion and allowing genuine comfort and Hoko Karnegis

Page 10 joy to arise is the true road to lasting contentment that isn’t based on the distractions of the illusory, disconnected small self. Practicing paying attention to our condition, our actions and the effect those actions have on others is the work of a bo-dhisattva, done for the sake of all beings rather than just for ourselves. Rather than taking loving feelings of ease as a per-sonal reward, the bodhisattva makes them available to all. No one knows any more who asked and answered the ques-tion, “Why were the saints, saints? Because they were cheerful when it was difficult to be cheerful, patient when it was difficult to be patient; and because they pushed on when they wanted to stand still, and kept silent when they wanted to talk, and were agreeable when they wanted to be disagreeable.” The demands of the small self may sometimes manifest as ill temper, impa-tience, indolence, idle speech and disagreeableness. The bodhi-sattva, on the other hand, manifests love and good cheer rather than indulging in anger, even though that’s not always so easy. We may think, “Today hasn’t been such a good day. I have every right to be annoyed. Bodhisattva practice will have to wait for another day, when things are going my way and I feel more upbeat.” Yes, in the face of the obstacles and frustrations of our lives, it’s tough to be cheerful. That’s when we really need to practice. What more important time or opportunity is there for practice than when good cheer seems far away? It’s fairly sim-ple to enjoy the good times. The real test of our practice is our ability to appreciate the bad times as well, because we know we cannot escape them. When our outlook isn’t completely tied to the likes and dislikes of the small self—when our goodwill is selfless—love and cheerfulness arise naturally. Hoko Karnegis

Page 11 Sabine Karner Mossy Bricks Danville, Indiana

Page 12 During Metronomic returns returning. From not to being, womb to world. Day folds dark to light to dark, returning to nearly not, turning to be – not. Lisa Summers

Page 13 Each Week Each week, I step across stones Remove my shoes and with bare feet feel the cool wood press parts of my skin barely touched Each week, I bring my mind who constantly roves and like a wayward pet shakes the leash, And each week together we cross a threshold facing only ourselves -A breath pauses- then escapes a silent sigh. Kristin Roahrig

Page 14 Frosted Leaves Hendricks County, Indiana Sabine Karner

Page 15 Landing Seeds fall first, right? Take a look at your face in the mirror before you were born. Or... Seeds fall last, yes? Weighing down branches, slipping their sockets like teeth freed of their dead. Watch them reel: mornings, stars, stones— observe how snowflakes reveal the breeze until they land. And you? Long before your mother’s womb, your hand cast a fistful on the current— Wait! Or hurry. Nothing lands wrong. Lisa Summers

Page 16 The Lure of the Midwest – A Transcription of Michael Komyo Melfi's interview of Shohaku Okumura Roshi The following comments were transcribed from a YouTube video of Michael Komyo Melfi's February 2019 video interview with Okumura Roshi, the founder and abbot of Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana. Komyo: You established your temple, Sanshin-ji, in the Mid-west, a center of conservative Christianity. Okumura Roshi: One of the reasons I decided to locate Sanshin-ji in Bloomington is, before I moved here to Blooming-ton, I lived in California and I worked for Sotoshu International Center. One of the tasks of that center was to build a bridge be-tween Japanese Soto tradition and American Soto Zen commu-nities. That was 1997. At that time within American Soto Zen community there was no sense of community. Different lineages like the lineages of Suzuki Roshi, Katagiri Roshi, Maezumi Roshi and the lineage established by Jiyu Kennett Roshi- those line-ages were kind of independent and they didn’t have a sense of community. Another task of that center was to promote a sense of community with American Soto Zen centers. So, I visited many Zen centers from all those lineages and met many American teachers and American practitioners. When I knew I had a clearer image of American Zen, I felt I didn’t want to establish my practice center in West coast or East coast be-cause there are already so many Zen centers and so many Zen teachers. So I didn’t want to make another one and become a kind of competitor with American Zen teachers. It seemed Indi-ana was kind of a frontier and Uchiyama Roshi, my teacher, always expected us to be a pioneer. I knew there was no Soto Zen center in the state of Indiana, at all. There was a small Zen group in West Lafayette, other than that there was no Zen cen-ter in Indiana. So I thought, if Buddhism or Zen can survive in Indiana, it can survive anywhere in the United States. (laughs) That was one of the reasons I moved to Bloomington. Shohaku Okumura

Page 17 On the West coast there are many people who never went to a western Christian church. So to practice Buddhism was very natural to those people. But here, Christianity is still alive, and for many people Buddhism is a kind of something strange. At least different from their spiritual tradition, so they have more resistance. But I think that it's a good thing for us to have an exchange or relation with kind of a traditional American spiritu-ality. That is another of the reasons I intentionally moved to the Midwest. So. I think so far I expected it is gradually, not rapidly, happening... so I’m happy about that. Komyo asked about the aspect of counter culture and its effect of attracting people to Zen centers... Okumura Roshi: Because of the hippie spirit or generation, Buddhism or Zen in the West coast, or probably East coast too, too-rapidly became American. They kind of transformed Zen practice into an expression of their ideal. So Zen practice be-came Americanized too fast. But in the Midwest there is no such mentality, so Buddhist practice or Zen practice in the Midwest can have a relation with more conservative traditional American spirituality. It might have been difficult if I create my sangha or practice center in California. I might have had more people, but I think when I see the history of Zen Buddhism in this country, to have a dialogue or conversation or exchange with more tradi-tional conservative American spirituality might have meaning instead of too easily and rapidly Americanized form of Bud-dhism. So it takes more time, but Buddhism can study from the traditional American spirituality, I think. Komyo: Do you find elements of American Zen practice that are unique in comparison with Japan? Okumura Roshi: I’m not sure because I am not American. (laughs) American people cannot practice like Japanese people so there must be some transformation. And this transformation hap-pened when Buddhism was transplanted from India to China and China to Japan. Some change happened. So, there’s no way Japanese Buddhism can be transplanted in America or other Western countries without transformation, without changes. Shohaku Okumura

Page 18 But my hope is that change is a gradual, slow process. Bud-dhism was transported from China to Japan in the 6th century. And it is said Buddhism really became Japanese in the time of Dogen, that is 12th or 13th century. So it took six or seven hun-dred years for Buddhism to really become Japanese Buddhism or part of Japanese culture. At least several hundred years. The same thing happened for Chinese Buddhism became really Chi-nese. But because of the development of transportation and commu-nications, so many things too rapidly transported to this coun-try. Some American people already think Zen is an American thing. That is fine but there are some more things that are kind of important and help to make American Zen or Buddhism rich. I hope this transformation goes kind of as a slow process. It’s too soon to become Americanized, and American people think that American Buddhism is different from Japanese or Chinese or Indian. Eventually that will happen, but I hope the process can be slow. Mark Howell transcribed porons of Michael Komyo Melfi's full interview with permission in November 2021. Komyo's full interview with Okumura Roshi can be viewed at hps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNHvaohA5Mk. Shohaku Okumura

Page 19 Glance to Reality With grounded strength, needles cling to the tree akin to the sharp pricks into my mind Thoughts, refusing - repeating stories of life all told in my own fashion the needles cling to a reality already gone traces of winter coolness of ground both needles of tree and mind reluctant to leave my perception to leap across my photo image into the reality beyond -Yet in the stillness on a night of falling snow a rip is at times seen displaying a stable peace one moment following another. Kristin Roahrig

Page 20 House Sitting My friend’s house expects an early riser, And, so, I’m up at five, picking my way over her dogs to start the fire. Once the sun is up, we set out into the pasture, shadows stretched over frost-rimed hills. Before, I’ve followed her lead, childlike, gathering hedge apples, helping her struggle with the one-hinged gate. Carefree, I thought the two creeks were a half-dozen, and delighted at how her house was always popping up on the horizon at some unexpected angle. Now, on my own, I begin considering: how might I avoid that muddy slope? Must I cross the creek so many times? Thinking so, it isn’t long before I know when and at what angle the house will appear. Innocence lets go as I curse the thorny invasives: locust and multiflora rose, catching at me as I go. Perhaps the dogs never lose the novelty I once enjoyed: mapless, cognitively naïve, they still wander as if it were all new. And me? Still avoiding mud, I’ve gotten turned around. I’ve no idea where I am. A locust thorn has hold of my collar, Lisa Summers

Page 21 a rose briar snags my leg. The dogs run ahead. Shaking myself loose, I climb after them over the next rise, and there, all unexpected, stand two horses against the sun. If only I could be astonished so easily by all that I love, but grow too used to—both landscapes and people. How much everything I know is like my friend’s pasture: creek-furrowed, cow-trodden, invaded by what seemingly does not belong. If only I refrained—or could—from finding my way by primary directions learned too well. If only north and south, east and west could be endlessly con-founded by what might appear at the top of the next rise: two horses staring in startled wonder at what their morning brought them. Lisa Summers

Page 22 Self-Care in the Era of Covid-19 – How meditation and yoga can help with pandemic-related trauma I’ve worked in the social services field for more than three dec-ades. I’ve been a practicing psychotherapist many of those years and this has become the lens that colors how I look at life, even though I no longer work in direct client care. As a therapist, if a client approached me with anxiety or trau-ma symptoms, I would roll out whatever clinical interventions I had been trained to use to treat those particular symptoms. But of course, in my own life, I had my own stressors and traumatic experiences to deal with. And when these issues came up for me, I instinctively turned to the practices of yoga and medita-tion as my own, personal coping strategies. This wasn’t because of some intentional plan to withhold useful techniques from my clients. I was simply performing my duties as a therapist in the way that I had been trained to perform those duties. I had been studying yoga and meditation since 1974, far longer than I had been in college, and these practices had become deeply integrat-ed into my life. I didn’t make a conscious decision to turn to these techniques when confronted with personal challenges, it was just something that I did instinctively. But a funny thing happened on the way to the Zendo. Over the years, I watched the behavioral health field gradually adopt vari-ous techniques and practices from Zen and yoga. At first, this went slowly. But by the 1970s, there had already been several studies on yoga and meditation, and the scientific evidence was beginning to stack up that showed that meditation and yoga could improve one’s “stress tolerance.” In other words, it helped you stay calm during challenging situations. In the early 1990s, a new therapeutic approach called Dialectical Behavioral Thera-py (or DBT) became popular, and one of its most prominent fea-tures is a strong focus on various “mindfulness practices.” It is now common to use various meditative techniques in clinical practice. Brad Uebinger

Page 23 And then, medical science developed powerful new tools for studying how the brain works. High-tech imaging technology such as PET and FMRI scanners have made it possible to study the brain in new ways. This technology enabled us to learn that trauma is stored in the deepest parts of the brain. These sec-tions of the brain don’t have the ability to process speech; they are more primitive parts of the brain that function on a pre-verbal level. This means that traditional talk therapy isn’t even the right tool for addressing trauma, since verbal interactions can’t reach the pre-verbal parts of the brain. Traditional talk therapy can help with certain aspects of your treatment, such as deciding which techniques to try, and it can help you inte-grate what you learn, but it can’t directly cause healing of the trauma that you’ve experienced. This is like having a flat tire on your car and trying to fix it by adjusting the carburetor. If you’re not even working in the right system, any attempt to “fix” the problem simply isn’t going to work. In 2014, Bessel Van der Kolk’s book “The Body Keeps the Score” described this new brain research and introduced some of the techniques that his clinic has been using to help people who have suffered from trauma. All of these techniques, such as EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing), Neu-rofeedback and Trauma-Informed Yoga (also known as Trauma-Sensitive Yoga), are designed to bypass the verbal, rational parts of the brain, and help people to directly access these deeper, pre-verbal parts of the brain. This is where the real healing of trau-ma can occur. These techniques have been extensively re-searched at Van der Kolk’s clinic, The Trauma Center in Brook-line, Massachusetts, and the results have been quite impres-sive. Many of the clients have reached the point where they no longer meet the clinical criteria for a trauma disorder. So, it’s now come full circle for me. The industry that I trained in professionally has assimilated some of the techniques from yoga and Zen that I had learned many years before I became a mental health professional. As I’ve watched the Covid-19 pan-demic tear through our society, I’ve thought a lot about how it has impacted our collective mental health. And I realized that, if I were treating people today who are experiencing pandemic-Brad Uebinger

Page 24 related anxiety and trauma, there would be a lot fewer clinical techniques that I learned in college and a lot more “mindfulness” techniques that I learned from studying yoga and Zen. Covid-19 isn’t just a physical health problem, it’s a trauma-inducing event on a global scale. Everybody has experienced some amount of emotional distress from the pandemic, alt-hough people have different degrees of awareness about how it has impacted them. Fortunately, there are many tools and tech-niques to help people manage stress and anxiety, and some of the most powerful of these are mindfulness-based practices. Some of the specific techniques that are being used in places like the Trauma Center require specialized training and must be provided by treatment professionals. For example, I spent sever-al months becoming certified in the EMBER model of Trauma-Sensitive Yoga, in addition to the 200 hours of training that it takes to become a yoga teacher. Some anxiety and trauma dis-orders certainly do require the help of treatment professionals. But I AM a treatment professional, who just happens to also be a yogi and a meditation teacher. And I believe that mindfulness practices could help many people to minimize the emotional scars of the pandemic. For those who need professional sup-port, these techniques are likely to be a crucial part of treat-ment. And many of those who do not need professional care could use meditation and yoga techniques to manage the symp-toms on their own. For many, it could be all that is needed. Meditation and yoga have been around for thousands of years, but they are still two of the most powerful tools available for ad-dressing the emotional side effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. If you are feeling emotionally fragile or stressed out, then it would certainly be worthwhile to consider learning meditation and/or yoga. There are plenty of opportunities to learn these skills, in-cluding some options that are free or at very low cost. Even though I’ve been a practicing psychotherapist for many years, I’ve often said that meditation is the single most powerful thing that we can do for our mental health. This may be even more true today than before the Covid-19 pandemic. Brad Uebinger

Page 25 Loren Malloy Mandala

Page 26 Your Day Changes, Mind to Mind I heard the words of this title in a podcast when the speaker tripped over his nouns. While he immediately corrected himself and moved on, I found this phrasing to be much more interest-ing and just as true as what he meant to say, and in two ways. First, your day changes as your mind changes and it changes profoundly. For me, this shift in mind can be difficult to recog-nize at the time it occurs and the shift is virtually impossible to steer. In the second sense, your day changes mind-to-mind. As you meet someone, maybe family at home as a day begins or a stranger in a checkout line, you exchange non-verbal queues through facial expressions, postures, and movements. With nothing uttered you exchange sentiment and emotion at a sub-conscious, mind-to-mind level. And your day changes. In his opening to The Bloodstream Sermon1, Bodhidharma re-sponds when asked what the buddhas of the past and future meant by ‘mind’: “You ask. That is your mind. I answer. That’s my mind. That which asks is your mind. Through endless kal-pas [unfathomable expanses of time] without beginning, whatev-er you do, wherever you are, that’s your real mind.” Given this, it is no surprise that your mind changes your day. Your state of mind when you ask will influence the other’s mind when they answer. Offer a smile and receive a smile. Bodhidhar-ma also said, “Buddhas of the past and future teach mind to mind without bothering about definitions.” Mind-to-mind trans-mission is so powerful that formal Zen tradition requires that teachings be transmitted mind-to-mind from master to disciple. This is because words cannot express reality. Dogen Zenji spoke of three minds in his Tenzo Kyokun. Trans-lated as Instructions for the Zen Cook, this writing is thought of as a real-life guide on how to live according to Zen principles. He wrote, “The Way-Seeking Mind of a tenzo [Zen cook] is actual-ized by rolling up your sleeves.” For me, this expression reveals values Dogen admired and transmitted throughout this teach-ing: Roll up your sleeves. Pay attention. Get organized. Take care of things. Do what needs to be done. And you do it- don’t wait for someone else. When you cook, just cook. In this way, Mark Howell

Page 27 the “mind and environment are innately one.” This is the state of samadhi.2 In Tenzo Kyokun, Dogen mentions Joyful Mind, Magnanimous Mind and Parental Mind. Joyful Mind or kishin is having a spirit of joyfulness regardless of the task. Keep a joyful spirit while peeling potatoes or shoveling snow. Keep a joyful spirit when cut off in traffic. Magnanimous Mind or daishin can be translat-ed as Great Mind. This mind is stable and impartial- without prejudice and refusing to take sides. It is the mind that devotes you to each and every thing you encounter. Parental Mind or roshin is an attitude of caring or nurturing that is applied to all one does. My grandfather would say that if all you have in this world is a piece of baling wire and you don’t take care of it, then you won’t have even that. I think this is what roshin means. Clearly, our days will change for the better if we just maintain these three Minds. Our difficulty is that our states of mind are transient. But minds can be trained and this is the importance of meditation practice. Kodo Sawaki said that a person is in one of three states when on their meditation cushion: sleepy stupor, thinking stupor, or zazen. The essential point of zazen medita-tion is to wake up from our stupors and return to our zazen posture. This activity of shikin-taza [just sitting] is the whole-hearted practice of enlightenment. Our meditation is a practice of being awake and aware. In this way it intimately coincides with the teachings of Tenzo Kyokun. This is why meditation is so important. With practice, awake and aware can follow us off our meditation cushion and into our daily life. You can be equally awake and aware while listening to beautiful music or having a difficult meeting with your boss. Maybe you will think of Joyful Mind, Magnanimous Mind and Parental Mind as your day unfolds. If you are able to occupy one of these minds your day will improve. And you will transmit this improvement to others, mind-to-mind 1. Bodhidharma and Red Pine, The Zen teaching of Bodhidhar-ma (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1989). 2. Dogen, Thomas Wright, and Kosho Uchiyama, Refining Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment, 1st ed (New York: Weatherhill, 1983). Mark Howell

Page 28 Single Grain Sitting within a desert each grain a particle separate but inseparable covering a vast space The sands steady me But it is the sky -The sky that interprets my mind reds, yellow, and blue showing all my colors vanity of colors chasing one another Look away an hour A minute A second Glancing again before me No sand No sky Into my palm a single grain falls, Encompassing. Kristin Roahrig

Page 29 Snow Covered Bridge Blanton Woods, Danville, Indiana Sabine Karner

Page 30 Contributors Mark Howell is a founding member of Great Wind Zendo and a husband, father and geologist. He received lay precepts from Shohaku Okumura in 2010 and trained with Hoko Karnegis and others. Hoko Karnegis is the vice abbot of Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, IN. She has led several sesshin at Great Wind Zendo. Sabine Karner has practiced Zen meditation for many years. She enjoys immersive creative pursuits of all kinds provided they require a good deal of patience and concentration. Sabine is a founding member of Great Wind Zendo. Loren Malloy's art has appeared in various print magazines and anthologies. Kristin Roahrig's short stories and poetry have appeared in numerous publications. She is also the author of several plays and lives in Indiana. Kristin is a founding member of Great Wind Zendo. Neil Schmitzer-Torbert began to study Zen as a high school student in Illinois, and attended the Dharma Field Zen Center in Minneapolis for several years while he was a graduate stu-dent in neuroscience. Since 2006, he has taught in the Wabash College Psychology department in Crawfordsville, IN, and re-cently began sharing essays reflecting on Zen practice and sci-ence on his site, neuralbuddhist.com. Lisa Summers lives in rural Indiana and is an avid naturalist and hiker. Her fiction and poetry have previously appeared in a number of literary magazines. She was introduced to Zen prac-tice at Great Wind Zendo.

Page 31 Contributors (continued) Brad Uebinger started his meditation practice and studying the philosophies of yoga and Zen in 1974. He met his first Zen mas-ter in 1979, and started formally studying Hatha Yoga in the 1980s under Lois Steinberg. He has spent time in an ashram, attended yoga and meditation retreats all over the U.S. and has studied with more than a half dozen Zen masters. Brad com-pleted his Yoga Teacher Training in 2015, and has taken ad-vanced Yoga Teacher Training programs at the Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in Massachusetts and the White Lotus Center in Santa Barbara, California. He is a founding member of the Great Wind Zendo in Danville, Indiana.

Page 32 Mark Howell Center Family Dwelling Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, Kentucky

Great Wind Zendo is a place for Zen Meditation located in Dan-ville, Indiana. We are open to the public and there is no charge for our programs; we are a 501(c)(3) non-profit religious organi-zation that is funded by donations. Anyone new to meditation is welcome. We provide meditation instruction on Thursday evenings at 6:30 p.m. Please e-mail us so we know to expect you. Our schedule includes weekly meditation every Thursday night from 7:00 to 8:00 p.m., morning meditation one Sunday per month from 9:00 a.m. to noon, and an annual multi-day Ro-hatsu sesshin in December. We also have a monthly World Peace ceremony and celebrate Zen holidays including Nirvana Day, Buddha’s Birthday, Bodhidharma Day and Enlightenment Day. Our web calendar is the best place to find our schedule. Great Wind Zendo 52 W. Broadway Street Danville, Indiana 46122 email@gretwindzendo.org https://www.greatwindzendo.org

Sky Above Great Wind - Ryokan