Return to flip book view

Message FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGOUR ANNUAL REPORT ON GLOBAL EDUCATION | SPRING 2024DESIGNING COMPETENCY-BASED TRAVEL PROGRAMSSTUDENT ACTION ON GLOBAL ISSUES: SHAPING TOMORROW'S LEADERSCO-DESIGNING A NEW STORY OF GLOBAL LEARNINGINTERCONNECTED

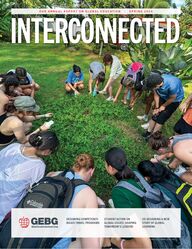

FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGSenior StaffCLARE SISISKY, Executive DirectorELSIE STAPF, Director of OperationsCHAD DETLOFF, Director of Professional Learning and CurriculumLEAH ROCKWELL, Operations ManagerBoard of DirectorsOfcersCHAIRLAURA P. APPELL-WARREN, St. Mark’s SchoolSECRETARYROB MCGUINESS, Appleby CollegeTREASURERDANIEL EMMERSON, GoodNotesBoard MembersTRICIA C. ANDERSON, Pace AcademyKARINA J. BAUM, Buckingham Browne & Nichols SchoolMELISSA A. BROWN, Holton Arms SchoolDAVID COLÓN, Visitation AcademyDION CRUSHSHON, The Blake SchoolANN DIEDERICH, Polytechnic SchoolJEN EVERS, The Heads NetworkYOM FOX, Georgetown Day SchoolJOHN HUGHES, The Lawrenceville SchoolKEVIN MURUNGI, Brooklyn Friends SchoolSOPHIE PARIS, Miss Porter’s SchoolGLEN TURF, Miami Country DayAbout GEBGThe Global Education Benchmark Group supports schools as they prepare students for a culturally diverse and rapidly changing world. We are the leading K-12 global education organization that provides professional learning on model practices and shares data and resources for schools as they develop teachers and students with the intercultural competencies to embrace and thrive in our interconnected world.3407 S. Jefferson Ave., Suite 71St. Louis, MO 63118(888) 291 GEBG (4324)www.gebg.org@gebgcommunicateDesign by Karnes Coffey DesignCover photo by Cate Rigoulo, Miss Porter's School Faculty INTERCONNECTEDTABLE OF CONTENTS | SPRING 20243Cover image: Miss Porter's School students learning about the Mimosa Pudica or Sensitive Plant and its traditional uses to treat a variety of digestive disorders during an activity with a local ethnobotanist in Chilamate, Costa Rica.Below: Faculty, from numerous GEBG member schools, in Cape Town participating in GEBG's summer program on the role of the arts in racial justice movements in South Africa.4 Perspective: Letter from our Editor5 Designing Competency-Based Travel Programs8 Loomis Chaee Schools’ Work On Student Action Through Its Various Centers12 Learning to Listen. Listening to Learn.15 Co-Designing a New Story of Global Learning with Students 19 Learning With Students: Virtual Exchange And Language Learning23 GEBG Global Summit on Climate Education24 Benchmarking Data Report34 Member School List37 Announcing the Salomon Prizes38 2024 Recognitions40 Global Educator Profiles: Cecil Stodgehill Ana Romero42 Impact Report

By Clare SisiskyBELOW LEFT:Cyrus Carter and attendees of GEBG European Regional Meeting hosted by Felsted School (UK) in November, 2018BELOW RIGHT: Cyrus Carter, in red, with GEBG Educators from Turkey, Switzerland, the UK and US in Cambridge, UKThis school year has been a challenging one for those dedicated to global education, and many leaders have been dismayed by the surprise of their colleagues that events happening in places far from campus can have a significant impact on campus. These challenges remind us, however, that the work of helping the adults and young people in our communities understand how cultures and communities are interconnected is not only important but is also essential for every teacher and student. One of the strengths of GEBG is our community of educators who share not only their examples and resources with each other, but are there for each other to provide stability and support in a year of instability and uncertainty. The GEBG community of educators has been providing this for each other since the first gathering in 2008. While many of those first schools were in the United States, pretty quickly a key feature of GEBG was the international community built around a common commitment to global education - a commitment to bringing global issues, global perspectives, and global experiences to our students. From some of these earliest days of GEBG, Cyrus Carter from Robert College in Istanbul Turkey was an active contributor to both sharing practices and building partnerships of collaboration. Cyrus inspired many in the GEBG network over the last ten years with the programs, conferences, and courses he created to ensure his Turkish students were not only connected to their peers around the world but were able to share their own ideas and perspectives, and take meaningful local action on global issues. Head of School at Robert College, Adam Oliver, described Cyrus as an educator with an “unwavering dedication to teaching and a genuine passion for nurturing young minds… He touched countless lives with his warmth, wisdom, and enthusiasm for education.” For those of you who did not have a chance to connect directly with Cyrus, you have likely inadvertently benefited from one of his shared resources, or an adaptation of one of his programs replicated at another school, or engaging your students with his students in Turkey through the GEBG Global Dialogues program. Although GEBG continues to grow and welcome new educators into the network, with new areas of focus and outreach, we remain at our core a dedicated community of educators connecting and engaging our students with the world. Being part of this community can mean that the influence and impact each of you have can reach well beyond your own school and students, and make us all stronger in our work and resolve. This year we dedicate our Interconnected magazine to Cyrus Carter, who’s passing on December 4, 2024 left many in the GEBG community recalling conversations, visits, or virtual collaborations with Cyrus over the last 15 years. PerspectiveA LETTER FROM OUR EDITORINTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 064

5FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGBY DR. ARIC VISSERFounder, Baserria Institute and Head of Secondary, British School of Navarra, SpainAs part of that process, schools have worked to articulate what their learning goals are for this kind of learning. Many schools are adopting competencies for global programs or as part of a broader strategy to focus on competencies at the whole school level. This is undoubtedly a good thing. However, for travel program designers and leaders, it has been dicult to apply the benefits of competency-based education at the micro-level, especially in the field. That is, when it comes to applying broad competency goals to individual programs or experiences, things seem to fall apart. And when it comes to assessing the program outcomes, we can often fall back into old habits of student satisfaction surveys or student self-report. This can be frustrating, especially after spending weeks, months, or years developing competencies for global programs.So the question is, “Can we use competencies as drivers for our global student learning experiences?” The answer is yes, but not in the way that I think many of us are trying to.Let me explain with an example. Most of us have a global competency in our list that looks something like “intercultural competence,” and rightfully so. If we are preparing students for the world that they will be living in, then we will need to teach them how to develop their intercultural DESIGNING COMPETENCY-BASED TRAVEL PROGRAMS In the past decade or so, schools with strong global travel programs have made great progress in assessing the effectiveness of these programs. After all, student travel is a tremendous amount of work, and as educators, we want that work to be “worth” something.

6INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06DESIGNING COMPETENCY-BASED TRAVEL PROGRAMS1. Build out your competencies.To make your bites a bit smaller, you need to create a structure in which each of your competencies is structured into three levels, each one progressively more specific. One level down from my six “competency areas” are more specific are “competencies,” and for my most specific level, I use the phrase “evidence of student learning” (EAL). Many schools use “I can” statements, but essentially at this level of specificity, the statements start to look like something you might see in a rubric.So for an example from my list, let’s look at Intercultural Competence, which is competency area 1 (CA1). At the competency level, I have roughly a half dozen competencies that fit in this area, including cognitive empathy, cultural emulation, cultural recognition, and Self-awareness. Each one of those has a fairly robust list of EAL statements, which are observable and assessable items that you can design activities around. A possible structure for this example, with definitions, looks like this:CA1: Intercultural Competence - The ability to communicate and eectively navigate the space in between cultures.If you truly want to apply competencies to your short-term programs, then follow the following steps.1. Build out each of your competencies to a three-tiered structure.2. Develop a list of Activity Approaches and use your competencies and approaches to plan individual activities.3. Always, and I mean always, include guided reflection in your planning.skills. An environment in a new cultural context is ripe with opportunities to work on these skills. The key here is “opportunity.” In my research and that of many others, intercultural competence development is often the assumed byproduct of international educational experiences. It is an assumption that is simply flat out wrong. Students are just about as likely to return home with a less developed skill set as they are to make progress on this competency.The promising thing about a competency like intercultural competence is that it can be measured. I tend to use the IDI in my work but the IDI (and other assessment tools) have their advantages and disadvantages. The problem with these instruments is that they tend to be based on theories that place intercultural competence on a developmental scale that is applied to a lifetime of cognitive development. Most global programs last less than a month. The greater majority fit into the place we like to refer to as “spring break” or “summer program.” The issue is not that IC can’t be measured; it’s just simply too big of a bite.Here’s what you should do instead.Like many schools, I work with a group of competencies that I have developed over the years through trial and error. I still think of my list as a “living document” and probably always will, but for now, all of my design work is based on six competency areas:✪ Intercultural Competence✪ Eective Communication✪ Collaboration and Immersion✪ Creative and Critical Thinking✪ Independence✪ Cultural and Environmental SustainabilityAs you can see, all of those are really, really big bites. While these may come into play for semester or year-long programming, I could never design a short-term program that tried to assess progress in any of these big competency areas in a meaningful way. Competency writing is dicult, and the application is even harder. So short-term program design and assessment needs a more focused approach. THE PROMISING THING ABOUT A COMPETENCY LIKE INTERCULTURAL COMPETENCE IS THAT IT CAN BE MEASURED.

DESIGNING COMPETENCY-BASED TRAVEL PROGRAMSCOMP: Cultural Emulation - The ability to mimic and adopt culturally appropriate models of communication in the target culture, including accent, tone, rhythm, and non-verbal forms of communication.EAL: Nonverbal communication - The student eectively uses hand, head, and body movements and non-verbal sounds to eectively communicate in the target language.Any activity that is designed to be eective in a global education environment can (and should) focus on more than one skill, but for the purpose of this exercise, let’s just stick with the one. Now that we have a three-tiered competency that is observable and assessable, we can move on to the next step.2. Develop a list of Activity Approaches and use your competencies and approaches to plan individual activities.If the competencies are the “what” of the design process, Activity Approaches are the “how.” These are categories that your activities fall into that will help guide you in your planning process. Some of the roughly 10 categories that I use are documentation, focused observation, engaging with locals, navigation, and perspective-taking. It is very important to understand that all activity categories are not created equal. I use documentation sparingly unless paired with at least one more approach. Students know how to take pictures of things, and it is not a particularly eective approach. Likewise, focused observation is a deliberate strategy of engaging in an environment with cues and rules of engagement, while simple observation is “seeing things in person,” and not particularly eective.For our non-verbal communication EAL example, I am drawn to using focused observation and engaging with locals, so I might design an activity in which I ask traveling students and a group of local students to observe the way each other communicates in a group setting and then ask students to pair up to share what they have observed. For the last step, I would ask each student, including the locals, to come up with a short monologue in which they mimicked the communication styles they observed and learned about from their partner, including non-verbal communication.So by starting with a competency, we go from students simply shadowing partner school peers to students engaging in a learning experience that is designed to get the most out of the student travel experience. But the last, and perhaps the most important step, is still left. Luckily for us, it is a simple one.3. Always, and I mean always, include guided reection in your planning.There are many places where you can read the research on experiential education and structures that work to make learning stick. There are even dozens of studies that look at eectiveness in global programs. The strategy that is more eective than any other? Guided reflection.In the middle of a busy itinerary, it may seem like a waste to carve out time for reflection, but without it, you can expect that a good portion of all your work developing competencies and approaches will blow away in the whirlwind of the next day’s travel. I like to think of the calculus of the importance of reflection like this:Competency-driven experience + no reflection = TourismNo experience + reflection = Navel-gazingNo experience + no reflection = BoredomCompetency-driven experience + reflection = Eectively designed competency-based global education.Putting it all together…Much like a well organized competency-based class, competency-based travel programs are a lot of work up front, with no guarantee that everything will work perfectly. But here’s the thing: Even if not perfect (and they never will be) international experiences based on a design of competencies and activity approaches will always provide a more robust and effective learning experience for our students. Think about it. If we are going to go through all of the trouble to fly halfway across the world, shouldn’t we expect them to return home with something more than “that was fun?” Let’s do the hard work. Our students will thank us. ■FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORG7

8ASHLEY AUGUSTINDirector, Center for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion We foster an inclusive school community through celebration of the diversity of its members; a sustained examination of privilege and biases; and the evolution of institutional policies, structures, and practices.MARLEY ALOE MATLACKDirector, Alvord Center for Global & Environmental Studies Our mission is to develop globally and environmentally engaged leaders who not only learn about the world and the environment but directly explore how they can play an active role in improving both.MATT KAMMRATHDirector, Norton Family Center for the Common GoodWe encourage an expanded understanding of students’ roles as citizens in a diverse democracy and foster an active, engaged approach to citizenship in our global society.SCOTT MACCLINTICDirector, Pearse Hub for Innovation (PHI)We are a central place where students can find the tools, faculty, and resources to flesh out their ideas and bring them to life.Tomorrow'sLoomis Chaee’s Commitment to Engaged Citizenship through Student ActionSHAPINGIn the heart of New England’s Connecticut River Valley lies an institution that not only educates but inspires in its students a commitment to the best self and common good. Loomis Chaee, an independent college preparatory boarding and day school for grades 9-12 and postgraduates in Windsor, CT, is so deeply committed to its mission that it has created a collaborative network of centers to help ensure that students, faculty, and sta have the space and support to carry it out. The centers epitomize Loomis Chaee’s innovative approach to education and oer an eective model for incorporating engaged citizenship and action-oriented learning into a curriculum. Our Contributors:LeadersINTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06

9FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGSHAPING The centers which focus on students each have distinct areas of expertise but work in tandem to deepen students’ understanding of the school’s mission. They act as idea incubators and resources hubs, empowering students to develop skills for navigating complex issues and transforming their concepts into reality through student action. This synergy of diverse specializations is vital for widening perspectives and fostering advanced critical thinking, pushing learning beyond the traditional classroom. Through this unique framework, Loomis Chaee has positioned itself as a pivotal force in nurturing proactive citizens and innovative problem-solvers for future generations. We have brought together the directors of these Loomis Chaee centers to share their thoughts on how the centers have had an impact on their community and why an action-based curriculum is critical in the development of engaged citizens. In your experience, how does the emphasis on taking action affect students’ learning process?Alvord Center for Global & Environmental Studies: When students are given the opportunity to participate in projects that have tangible impacts, the educational experience transitions from informative to transformative. This is especially apparent when we take students out of the classroom and into “the field.” Whether it is our French students having the opportunity to learn about Quebecois culture by making maple syrup at our sap house or meeting with local experts to learn about immigration patterns on a language immersion program in Marseille, France, students experience a mind shift when we incorporate action into the curriculum. Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: When learning is based on action, it provides relevance, and students become heavily invested. A perfect example of this is our recent collaboration with Seeking Educational Equity and Diversity (SEED), an organization focused on providing professional development seminars to communities that foster “personal, organizational, and societal change toward social justice.” In this collaboration, our students developed a valuable Left and below: I-Tri students using a human-centered design approach to tackle real-world challenges through the Pearse Hub for Innovation.“Our centers are the embodiment of Loomis Chaffee’s mission.”SHEILA CULBERT, HEAD OF SCHOOLSHAPING TOMORROW’S LEADERS

10INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06framework for SEED facilitators to use. The student-generated framework now serves as a catalyst for self-reflection and dialogue about our collective history and its current implications for faculty and sta at our school. Knowing that their framework is now being used in all of our trainings has made our students more confident in their ability to make a positive impact on our community. Pearse Hub for Innovation (PHI): Projects in PHI-based classes are typically partnerships with local businesses, nonprofit organizations, or on-campus organizations in which the students are tasked with designing solutions to solve real-world problems for their “client.” This fall, students in the PHI’s Problem Solving for the Common Good class worked with our Dean of Students Oce to design strategies to decrease student cell phone use on campus (in response to the recent Surgeon General’s report on the impact of cell phone use on student mental health). Knowing that their work would have an immediate impact on our community (and themselves) inspired students to go above and beyond our expectations. What are the key elements you consider when developing a curriculum that encourages students to take action? Alvord Center for Global & Environmental Studies: All of our curriculum is rooted in the Alvord Center Engaged Citizenship Matrix, a learning framework developed during our 2020 strategic planning process. The Matrix is a comprehensive tool that outlines our learning competencies and outcomes and provides its users (faculty and sta) with a common language to navigate our wide array of programs. We have found that through using a strategic approach to curriculum development, our programs are more cohesive and have a stronger connection to our mission. Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: When we establish a learning space that nurtures active listening, embracing humility, showing respect for diverse perspectives, exhibiting empathy, and building comfort with contention, students become empowered to ask themselves challenging questions, develop their understanding of diverse viewpoints, and open themselves to the art of constructive dialogue. Once this culture has been established, students are ready to take action. The Norton Family Center for the Common Good: We push students to think beyond the concept of what they want to do with their life and focus more on the idea of whom they want to help with their life. This is especially evident in two of our signature programs – the bi-weekly 9th- and 10th- grade seminar classes. Throughout the year, the seminars delve into topics such as leadership development, health and wellness, equity and inclusion, and engaged citizenship and then discuss how what we have learned can be applied to both our school community and the world beyond. This helps our students learn about opportunities to take action in week one of their time on the Loomis Chaee campus. Pearse Hub for Innovation: A key element in our approach is to start with the end user or target audience. Who are we designing and building for? What are their needs? Specific skills (design abilities) we are looking to develop include navigating ambiguity, learning from others, and communicating eectively. We believe that these skills are transferable to all types of problem-solving and work that involves students taking action and creating a world that does not exist yet with their ideas in it. How are students taking real-world action through these programs? Alvord Center for Global & Environmental Studies: In 2016, Jason Liu ’17, asked an ambitious question – Why couldn’t we power Loomis Chaee with solar energy? That question sparked a two-year educational experience that resulted in the installation of a one-megawatt solar array that now produces a third of Loomis Chaee’s electricity needs. Jason identifies his experience completing a solar power feasibility study, meeting with solar vendors, and presenting to the Board of Trustees as his most rewarding learning experience at Loomis Chaee. He also said that it was the spark that inspired him to become a PhD candidate in energy materials at Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering. Jason is one of many students who have experienced the transformative power of action-based learning in the Alvord Center. Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: Since 2021, we have had the opportunity to collaborate with the Loomis Chaee History, Philosophy & Religious Studies Department on a student-faculty research program titled “Slavery and Loomis Chaee: An Ethical History Project.” This project investigates the lives of Black people enslaved by the Chaee, Loomis, and Hayden families as well as the historical contexts in which they lived. When asked how this project has aected SHAPING TOMORROW’S LEADERSBelow: Jason Liu ’17 at Loomis Chaffee’s Solar Array Dedication Ceremony in 2019

11FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGSHAPING TOMORROW’S LEADERStheir experience at Loomis, a member of the class of 2025 said, “I have learned to understand history and the past as flowing currents that continue to influence and are inseparable from our present and future, and that has inspired me to invest more time into the ‘why’ things happen.” The Norton Family Center for the Common Good: Every year, we oer students the opportunity to apply for a Norton Fellowship Grant, which allows them to complete a community engagement project in their hometown over the summer. Last summer, we had students work with an immigrant community in Chicago, start a recycling program in Ghana, and teach introductory computer programming to underserved students in Hartford. All have come back to school and talked about the life-changing moment when they saw how their work aected the larger world. Describe an initiative or program you have that epitomizes your center’s mission and Loomis Chaffee’s emphasis on engaged citizenship? Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: We are especially proud of our initiatives and eorts to teach our community the art of dialogue. Dialogue is a cooperative process that involves participants coming together on a unified quest for common understanding. Whether it is via our student-facilitated Courageous Conversations series, our enhanced advisory group curriculum, or our training sessions for student leaders in the dormitories focused on understanding the nuances between “calling –in” versus “calling out,” our focus on dialogue is helping us nurture a more empathetic and engaged community. The Norton Family Center for the Common Good: One of the many ways the Norton Center encourages engaged citizenship is through our student-run Shultz Fellows organization. This non-partisan group of roughly 25 students with political leanings across the spectrum meets once a week to discuss current events. During these meetings, it is not uncommon for a conservative-leaning student to share thoughts and opinions with a liberal-leaning member of the group and vice versa. The goal of this organization is to encourage an atmosphere of civil discourse among individuals with dierent ideologies not seen in the typical “thought bubbles” seen in the news and on social media. Pearse Hub for Innovation: The Innovation Trimester (I-Tri) is an immersive capstone experience that gives students the time, space, and training to create something that will have a positive impact on others. Using human-centered design to examine problems faced by local businesses and nonprofit organizations, students learn project management techniques and skills to help them develop innovative solutions for real-world challenges. During the I-Tri, students develop a greater sense of awareness of their strengths and weaknesses and learn how they can bring their unique skills and abilities to projects in a valuable way. What advice would you give to other educators looking to incorporate more action-based learning into their curriculum?Alvord Center for Global & Environmental Studies: Incorporating action-based activities into your curriculum doesn’t have to be complicated. An incredible place to start is in your school’s backyard. Through leveraging your school’s unique setting, teachers can help their students develop a sense of place. Using this approach will transform your campus (and community) into a living laboratory full of new and exciting lessons to explore. Center for Diversity, Equity & Inclusion: Integrating action-based learning into your curriculum can be daunting at first, but its impact on the learning community makes the hard work worth it. Remember that it is OK to start small and then gradually increase the activities tied to action-based learning. Also, it is OK to ask for support and collaborate with people within your community who are passionate about this work and to come up with ideas collectively. The Norton Family Center for the Common Good: Don’t be afraid to try and fail, especially if you’ve involved the students in the brainstorming and planning process. There is just as much to be learned from a failed idea as there is from a success. Pearse Hub for Innovation: Lean into the potential discomfort and be willing to navigate the ambiguity that comes with not knowing what the end result or product is going to be or look like. Be thoughtful and intentional with your design choices. In the PHI we tell our students, “every decision and choice you make is an opportunity to design intentionally.” The same goes for educators. ■Below top: Norton Fellow Kavya Kolli ’20 drawing on her experience as a black belt in karate to give self-defense instruction to school-aged children living near her grandparents’ home in rural India.Below bottom: Loomis Chaffee's campus in Windsor, Connecticut, USA

12INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06LEARNING TO LISTEN.Capturing and comprehending the impact of these learning experiences on each of our 1,687 students presents a complex challenge. Every student has a unique journey characterized by interactions with educators, coaches, peers and the community that is further individualized by dierences in age, abilities, identity, experiences and levels of understanding. How might we capture the impact of a breadth of learning experiences on each student? What questions would yield insights to inform future learning experience de-sign? Additionally, do we have the capacity to process the volume of information such an approach might generate?Driven by these questions, I began to explore the capabilities of SenseMaker, a software ecosystem developed by The Cynefin Company, well known for its pioneering work in applied complexity science. This exploration laid the groundwork for my GEBG action research fellowship, prompting me to consider whether SenseMaker could deepen our understanding of each student’s journey of self-discovery and its relation to Collegiate’s Portrait of a Graduate traits. Supported by administrators, with input from a range of faculty and in collaboration with Liz Haske, a 5th Grade Humanities teacher and Technology Integrator, we began to learn about and build a SenseMaker frame-work in January 2023. Under the skilled and patient guidance of Anna Panagiotou of the Cynefin Company, our work culminated in the launch of Collegiate’s first JK-12 SenseMaker in March 2023. BY TRINA CLEMANSDirector of Economic and Entrepreneurship Education and the Director of the Cochrane Summer Economic Institute at the Collegiate School in Virginia. She was a GEBG Action Research Fellow in 2022-2023. The Powell Institute for Responsible Citizenship at Collegiate School collaborates with faculty to design learning experiences to nurture and equip its students as scholars, citizens and leaders. We foster students’ personal and academic growth, knowing each experience impacts learners in unique ways. Students practice applying what they know and meaningfully contribute to our school, community, and the broader world. Listening To Learn.

Above: Frank Becker, Lower School Engineering teacher, explains to a 1st Grader using SenseMaker for the rst time how to drag and drop “stones” so he can independently assign meaning to his reection.Below left: Collegiate SenseMaker Student Triad and Dyad examples as a guide as well as a matrix of stick gure illustrations.Below right: Middle School Students Cross-referencing a triad with a multiple choice question.SenseMaker FrameworkSenseMaker captures narrative reflections, encapsulated in our framework through students' responses to a recurring prompt:"Thinking back on (your learning experience), what do you now realize? What helped you realize this?" When asking students to engage with the SenseMaker framework, faculty and coaches specify the learning experience for students to contemplate, and the students then have the opportunity to articulate their reflections by typing, recording and including an image if they decide to do so.After completing a written or recorded reflection and maybe providing an image, students attribute meaning to their learning experiences, generating quantitative data using SenseMaker’s unique question formats known as stones, dyads and triads. In our framework, students interpret the significance of their experiences by placing up to three dots, or “stones,” on a 4x3 matrix of stick figure illustrations representing the schools' values and a triad reflecting the school's portrait of a graduate. A sequence of six triads are then presented to students, each illustrating the comparative significance of three concepts. These triads serve to uncover underlying attitudes and values, proving particularly beneficial in exploring trade-os. Students then assess the strength of their beliefs using a dyad slider, marking their position on a spectrum between two endpoints described as either mutually positive or neutral.Concise sets of carefully considered multiple-choice questions are presented at the conclusion of the SenseMaker framework. The questions are tailored to refine data collection. They encompass various topics, such as the location of a learning experience, the duration of student enrollment, the student's grade and division and the nature of the experience — ranging from “strongly positive” to “strongly negative” or “very rare and unique” to “happens every day.”SenseMaker's continuous data capture feature means our educators can use the framework anytime and as often as they want. They then request a summary report of their students’ reflections and data visuals across dierent time frames, currently spanning nearly 12 months. The Powell Institute for Responsible Citizenship can query larger data sets enabling us to find emerging themes, patterns and outliers within and across learning experiences. It gives us the ability to process the volume of information we are accumulating to then make decisions about program design.Whenever a question arises during data review, we can directly consult the student's qualitative reflections that correspond to each quantitative data point. This integration of qualitative and quantitative LEARNING TO LISTEN. LISTENING TO LEARN.Listening To Learn.13FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORG

14INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06insights significantly diminishes the risk of faculty and sta biases creeping into our interpretation of student learning experiences, ensuring a more accurate and comprehensive understanding. A year into our pilot, we have collected 814 1st-12th Grade student reflections. In addition, we tested the framework during a teacher professional development summer project, which captured 31 teacher reflections, as well as during a Lower School capstone share, when visiting community guests submitted 46 SenseMaker reflections.Understanding Students’ Learning JourneysDuring my GEBG action research fellowship, it became clear to me that SenseMaker could significantly deepen our understanding of each student’s self-discovery journey and its connection with the Collegiate’s Portrait of a Graduate. However, to maintain student anonymity, we decided not to use the individual tracking feature, even though it is available. As a result, we are not able to track the trajectory of each student. Despite this, SenseMaker has proven invaluable in enhancing our collective grasp of the impact of learning experiences on our students, providing insights without compromising the anonymity of individuals.Teachers utilizing this tool are benefiting from transparency and collaborative sense-making in partnership with the Powell Institute for Responsible Citizenship. Teachers are also discussing the data visualizations with their students, generating in-class conversations that provide valuable insights into evolving student learning and experiences. SenseMaker is also fostering cross-disci-plinary connections without imposing high demand on faculty’s time. Simultaneously, the SenseMaker database is growing as a repository of institutional knowledge, a collective memory built on the lived experi-ences of students shared by students. What’s Next?With a year of trial and error under our belts, we look forward to continuing to learn with and from the Cynefin Company while diving into an emerging set of new questions.We want to explore which of our framework questions are performing as expected, and which might benefit from further research and restructuring? Could periodically separating the Sense-Maker reflection process from the class-room setting, thereby encouraging students to independently identify and reflect on their learning experiences, oer fresh insights on Portrait of a Graduate? What new under-standings might this independence reveal?What if we imagine the Portrait of a Grad-uate, as suggested by Beth Smith of the Cynefin Company, less as an exoskeleton and more as a flexible endoskeleton? Could this conceptual shift foster more organic, student-led growth, potentially unlocking richer learning experiences? Might this ap-proach empower students to more actively shape their identities with more opportunity to nurture their own learning journey?Curiosity continues to drive us, and we have established a good direction of where our exploration is headed. The SenseMaker pilot significantly benefited from Clare Sisisky’s expertise and the collaborative insights of my GEBG fellowship cohort. Their probing questions guided dialogue and methodical reflection on this complex challenge, consistently grounding my approach in the central guiding question.Together with my Collegiate colleagues involved in the pilot, we are excited to further explore SenseMaker and more fully leverage its capabilities. Despite the tool’s initial learning curve, it has proven to be surprisingly user-friendly. I believe it holds immense promise as we facilitate a more nuanced dialogue with our students, enriching our insights into their distinctive experiences shaped by the educational journeys we curate. ■LEARNING TO LISTEN. LISTENING TO LEARN.TEACHERS ON USING SENSEMAKER“I love using SenseMaker! It is a great tool to collect data on our students’ experiences. The data allows me to gain insight into my students’ perspectives on their learning and allows me to adjust and rene their experiences to ensure they are student-centered, progressive and engaging.” LOWER SCHOOL GRADE-LEVEL LEAD TEACHERSTUDENT REFLECTIONS CAPTURED BY SENSEMAKER“I realized how hard it is to immigrate and that we should give everyone some grace when they have just moved. I just now realized that most people that move, move for a reason.” LOWER SCHOOL STUDENTS“I realized how much we as people from the Upper School value schedules, specically relating to our inability to accept exible schedules. I had to set aside my attachment to schedules, especially as we are so used to set calendar dates and times as a community. Overall, I learned how to adapt to new situations and to extenuating circumstances while learning about new things I never knew I knew.” UPPER SCHOOL STUDENT REFLECTION FROM PARTNER SCHOOL VISIT

15FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGProcesses of migration, travel, technological inno-vations, and a myriad of global and local issues that bind us as humans necessitate that schools continue evolving their programs and creating opportunities for students to actively engage in global learning to devel-op the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to meet the challenges of their generations. Global learning opportunities take place on school campuses, during immersive learning experiences, and, more recently, online. Like many other schools, Brewster Academy has been oering courses that expose students to a variety of content, particularly in English and history classes. In the World Language classroom, students practice communication skills and cultivate an appreciation and respect for the products, perspec-tives, and practices of the people whose languages are being studied. As a boarding school, we also have a BY STEVEN DAVISWorld Languages Chair and GEBG Action Research Fellow in 2022-2023and DR. MARTA FILIP-FOUSERDean of Teaching and Learning at Brewster Academy in New Hampshire, USAA NEW STORY OF GLOBAL LEARNING WITH STUDENTS robust international student population which creates opportunities for intercultural learning through informal gatherings or school-wide events. But a few years ago, when the idea of opening our first international campus in Madrid, Spain, became a reality, it also created a sense of greater urgency around global education and an opportunity to build more intentionality and student agency in our global programs.In his book, Creating Cultures of Thinking, Ritchard (2023) writes that to create learners who feel a sense of empowerment, i.e. those who realize and pursue their passions in ways that are independent and meaningful, schools need to shift the architecture of learning and rethink the roles of students and teachers. As teachers, we need to scaold opportunities for students that help them assume responsibilities, develop their dierent identities, and position them as active co-creators in the processes of program design. We need to practice observing and listening more to our students to under-The “Why” of Global Learning at BrewsterCo-Designing

16INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06stand their needs and to create environments that allow them to thoughtfully engage in a myriad of experiences. With these principles in mind and grounded in our school’s mission statement, “To prepare diverse think-ers for lives of purpose”, we devised a three-pronged framework for developing our Global Scholar Program that launched in the fall of 2022 and piloted it during the 2022-2023 school year. The overarching framework for our Global Scholar Program comprises three pillars that, taken together, help students discover interests, consider contributions to their communities, and reflect on their changing and multiple identities. Students take academic classes, engage in immersive experiences on campus or in local areas (e.g. by attending and pre-senting at youth conferences and events or traveling as a cohort), and through either individual or school-spon-sored global trips, advance understanding of the world and develop competencies that build their appreciation for others and the propensity to act upon issues that they care about.Co-Design with Students as the Underlying Approach in the ProgramThe inaugural meeting of our pilot year brought to-gether a cohort of thirteen eager juniors, seniors, and post-graduates and was structured around a constella-tion of pithy, yet powerful questions: What does it mean to advance ethical, global citizenship in all aspects of your life? What brings you to this space and to the program? And what do you seek to achieve in helping co-construct and steward the stakes of this pathway at the school? Amidst the laughter, the questions, the cu-riosities, and the doubts around the table, we said and prompted little, positioning ourselves only as a witness as students named all which they observed in our many spaces on campus in the hope that from the tangle would emerge a common purpose that would act as a substrate for us to build upon and scale. More than an initial moment of connection and of conversation, how-ever, this discussion and subsequent gallery walk of scribbled down goals and noticings saw the beginning of a rhythm that provided ample and regular space and time to come together in dialogue in order to articu-late the many threads of the cohort’s social reality as well as to generate new understandings. Discussing and unpacking a range of relevant topics from various vantage points, from student leadership to climate action to mental health to gender equity, students felt increasingly empowered to critically observe, own the issues that defined their community, and crowdsource knowledge that deeply resonated with the many ‘whys’ that brought them to the program initially.The elements of observing, listening and engaging are woven into the overarching structure of our Global Scholar Program that help students discover inter-ests, consider contributions to their communities, and reflect on their changing and multiple identities. Many of our Global Scholar Program students enroll in a research-based course the theme of which focuses on developing a greater understanding of one’s civic identity, i.e., who one is and how one relates to others and other communities. While during the first trimester, students focus on exploring the overarching essential question (“What Makes a Citizen?”) through various interdisciplinary lenses, the rest of the year is entirely driven by students and allows them to ponder, explore, and research topics and ideas related to their interests. For example, last year, students’ individual research explorations and presentations to the greater commu-nity ranged from topics on sustainable architectural designs, the role of indigenous knowledge in risk reduc-tion, or resilience building among minoritized popula-tions in the United States. The opportunity for students to make choices and create experiences that are linked to their emerging interests and identities gives them a sense of empowerment and provides a platform to practice many transferable skills.Taken a step further, thoughtful participation in and ac-tion on the world must involve reframing learning itself as an agentic process, not a specific outcome, not least because living and being in the world is invariably built upon an ever expanding cycle of inquiry, discovery, and reflection. As Paolo Friere posits in his text Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), it is through praxis upon the environment that one is able to critically reflect upon reality and ethically transform it through further action and reflection. From participating in GEBG student dialogues and stewarding anity groups and clubs on our campus to organizing sustainable clothing swaps, attending conferences and workshops, and leading broader initiatives with a global reach, students in the program are emboldened to act on behalf of their community and the world, transforming it for the better and improving the underlying conditions of humanity in the process.As part of our annual experiential learning term, global scholars participated in a two-week-long immersion in New York City during which students delved into the complex stakes of peace, sustainability, and citizen-ship. More than providing an opportunity for students to cultivate a deeper appreciation of the role various local, national, and international organizations play in promoting engaged citizenship, peace, and sustainable CO-DESIGNING A NEW STORY OF GLOBAL LEARNING WITH STUDENTSWE NEED TO PRACTICE OBSERVING AND LISTENING MORE TO OUR STUDENTS TO UNDERSTAND THEIR NEEDS AND TO CREATE ENVIRONMENTS THAT ALLOW THEM TO THOUGHTFULLY ENGAGE IN A MYRIAD OF EXPERIENCES.

17FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGdevelopment, the immersion allowed students to view and listen to New York from simultaneous and gradu-ated vantage points. Students considered at once the role the city plays in shaping the international political, economic, and cultural landscape as well as, for exam-ple, how a city-wide commitment to sustainable devel-opment, equity, and social justice are brought to bear on these broader discourses and policy goals. Follow-ing our time together in New York, students returned to Brewster emboldened to reimagine institutional priorities, systems, and structures to better empower those in our community to organize and lead change around these issues. In all, the combination of individu-al pursuits and collective endeavors helps build agency while also creating enduring opportunities for those in our care to learn, grow, listen, and connect with others in service of something greater than themselves. Listening as a Vehicle for IterationTo listen is to allow oneself to be changed by another, not in one’s sense of self but in one’s underlying hu-manity and view of the world. This thread is one which is woven throughout the program, both as an active component of its genesis and a point of constant be-coming for students, signaling a moving guidepost that we hope our students will honor as they continuously co-construct the stakes of the pathway with us and ac-tively strive towards in cultivating an understanding of self and the relationship it shares to the broader world by means of intercultural awareness and perspec-tive-taking. With this in mind, the listening that we fore-ground in the architecture of the program and our work of guiding students must rely on an understanding of the importance of human connection, storytelling, and compassion as an unwavering north star. It is through listening that one feels connected to other people and places and helps us to understand ourselves as part of larger, interconnected systems. This is our hope for our students in the program, not least because meaningful action to address the complex problems that they will inherit as young people first requires a full, nuanced understanding of the interrelationships that integrate elements of the complex systems that define their world. As part of an action research fellowship conducted last year in partnership with GEBG, we leaned into the possibilities of student feedback and perspectives to manage change and guide the future direction of the program. Two separate, semi-structured focus groups with students in the program were undertaken over the span of a week using a pre-generated list of ques-tions that explored the degree to which the learning architecture of the program provided meaningful, authentic opportunities for learners to demonstrate growth towards the propensity to take action in service of collective well-being and sustainable development. The resulting conversations were robust and nuanced, with students oering rich perspectives about their own learning during their time in the program as well as invaluable anecdotes and thoughts on the intentional-ity of the pedagogical architecture at play; experiential opportunities provided by the program; and some of the growth edges to bear in mind as we look ahead. What’s more, the conclusions that emerged from the coded student responses provided us with increased clarity around the ways in which we might continue to iterate with learner outcomes in mind, including redesigning the program to further enhance equity and expand and enrich partnerships and experiences such that all students in the program are aorded sucient opportunities to pursue individual passions and inter-ests and meaningfully grow toward the competencies and outcomes articulated by the pathway. The Criticality of Adult Learning and Faculty-Student Joint OpportunitiesTo promote a culture of learning in which students feel empowered as co-creators of their experiences, as educators and school leaders we also needed to create opportunities for teachers to experience similar environments. To this end, the purpose and structure of our professional learning opportunities have focused on expanding teachers’ knowledge of global compe-tencies and learning but also on devising a format that TO LISTEN IS TO ALLOW ONESELF TO BE CHANGED BY ANOTHER...IN ONE'S UNDERLYING HUMANITY AND VIEW OF THE WORLD.CO-DESIGNING A NEW STORY OF GLOBAL LEARNING WITH STUDENTS

18INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06Questions? Contact us at info@experiment.org.creates a platform to explore ideas, critically examine, and evolve our pedagogies. For the past couple of years, our PLCs have intentionally combined the what and the how of our practice with the ultimate goal of making changes to our instructional approaches and assessments. During our bi-weekly PLC sessions, facul-ty discuss individual problems of practice, brainstorm ideas, test them, and reflect on the changes they make. Be it incorporating global competencies into our cur-ricula, leveraging Artificial Intelligence, or embedding social-emotional learning into teaching and learning, those conversations are important elements in evolving our classroom approaches and better understanding what conditions allow students to engage deeply.Challenges and the Path ForwardWhile it has been exciting to guide students through the program, help them find and articulate their passions, and act upon them, this work has not been without challenges common to piloting new initiatives. Embedding cohort meeting times into boarding school teenagers’ busy schedules at times proved dicult and most of our meetings took place in late afternoons or in the evenings. However, the greater and more com-plex challenge of the program, and any program that assumes co-design as the core approach, is directly re-lated to an organization’s culture of teaching and learn-ing. To us as a school, the pilot of the program presents an opportunity to place a greater emphasis in our daily routines on pedagogies that shift even more towards student agency and create environments in which stu-dents situate themselves at the center of their learning experiences. As we settle into our second year in the program, this new cohort of students has inevitably informed its dynamic, lending their own interests and passions to the contours of what we pursue and which threads we tug on. Much like our students, we too must lean into, act on, and reflect on the process of what is and what could be. Amidst the becoming, what’s clear, however, is that we may also remain confident in the knowledge that our approach centers that which is most important: student capacity and flourishing in an interconnected, complex world. ■CO-DESIGNING A NEW STORY OF GLOBAL LEARNING WITH STUDENTS

Through class observations, surveys, focus group interviews, and student artifacts, I found that VE, as a component of intentional global education, developed global competence in meaningful ways, improved my students’ Spanish language skills, and expanded their technology skills. With the school’s mission being in part “to develop in each student … a sense of responsible purpose, and a determination to serve the world with courage, grace, and compassion,” Santa Catalina launched a global education initiative in 2020 to develop a more intentional PreK-12 global DEVELOPING GLOBAL COMPETENCEThe action research project investigated how virtual exchange develops global competence in high school girls in a Spanish 3 Honors language class. The project involved a diverse group of eight 15- to 17-year-old girls in an all-girls boarding school in Monterey, California, USA, who engaged in numerous virtual exchange (VE) sessions with students at two all-girls schools in Barcelona, Spain and Toronto, Canada using Spanish as the lingua franca.THROUGH VIRTUAL EXCHANGE IN THE SPANISH LANGUAGE CLASSROOMBY DR KASSANDRA BRENOTDirector of Global Education at Santa Catalina School in California, USA and GEBG Action Research Fellow in 2021-2022curriculum. VE should be championed as an important component of global education because it connects students internationally defying geography and travel access inequities, and spurs students to investigate the world, recognize perspectives, communicate ideas, and take action. In a school with a diverse student body (nearly half of the boarders are international, and 47% of the Upper School study body are students of color), VE should be championed as an important component of global education because it helps students develop skills related to communication and perspective taking. 19FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORG

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODSAfter a literature review focused on virtual exchange (VE) in the language classroom, this action research study utilized the research question: How does international virtual exchange develop global competence in 15- to 17-year-old girls in the Spanish language classroom? An action research methodology allowed me to take a problem-solving approach to study, reflect on and improve my teaching with participants in one section of Spanish III Honors. To ascertain how my students developed global competence, I amassed data by way of questionnaires, focus group interviews, research observations, an observer’s field notes, work samples, and classroom artifacts as preparation for and by-products of VE. The deliberate use of various data sources aimed to polyangulate the data, increasing the trustworthiness of my findings while trying to account for bias (Mertler, 2020). I conducted inductive data analysis of the various data sets to identify and code common themes, and shared my initial findings with colleagues for feedback. The study focused on 15 class meetings, during which my students participated in multiple asynchronous VEs (AVEs) and synchronous VEs (SVEs). The exchanges centered on United Nations Sustainable Development Goal #2: Zero Hunger and pandemic-induced food insecurity. The students in this study participated in a Spanish Lingua Franca model of VE. The lingua franca VE approach incorporates the basic tenets of global citizenship education, moving away from the bilingual-bicultural approach. Lingua franca VE involves students from various countries using one common language for their online interactions and involves tasks that require collaboration on a given theme or themes. DISCUSSION OF FINDINGSMy analysis of data indicated that VE demonstrably develops girls’ global competence by providing opportunities for them to interact internationally with peers from diverse backgrounds and perspectives.VIRTUAL EXCHANGEFINDING 1: Virtual Exchange can spur students to be curious about the world beyond their immediate environmentFraming our VEs around UN SDG #2 gave the students a focus. It spurred the students to investigate a major global challenge experienced in our community as well as in their VE partners’ communities. All the students expressed their desire to learn about hunger with their VE partners. The VE activities, whether synchronous or asynchronous, prompted conversation, built trust and expanded horizons. Prior to the VEs, none of the students knew of the existence of the two other girls’ schools: “a highlight for me was just learning in general about this other school” (Student 4). The students’ curiosity was piqued after reading international articles about hunger in each of the VE communities. Student 3 stated that she had no idea beforehand of the severity of food insecurity in Monterey County, much less in Barcelona or Toronto: “so now I care about what’s happening [in] the world. And I was think[ing] about what I can [do] to help eliminate or reduce hunger.”FINDING 2: Virtual Exchange can help students to recognize different perspectivesThe students’ ability to recognize and appreciate their own and others’ perspectives, cultural dierences, and similarities, increased. The students involved in the VEs represented a number of nations and cultural backgrounds, not only American, Canadian and Spanish, but also African, Asian, South Asian, and Latin American. These national and cultural dierences did not seem to divide them. Student 1 said “we’re all dierent but similar in multiple ways, which was really fun to learn about.” Student 4 specifically mentioned the importance of connecting with girls around the world, pointing toward the ability to identify influences on perspectives, “I believe that the value is in gaining an insight to the lives of fellow female students around the world… gaining benefit in exchanging and learning about others’ way of life across the globe.”INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 0620

VIRTUAL EXCHANGEFINDING 3: Virtual Exchange can push students to communicate ideas effectively in a language other than their ownVE gave the students the space to connect and develop their communication skills. They worked to articulate their ideas clearly, ask questions, engage in conversation, and collaborate. As Spanish language learners, the students reported growth in all four language skills: reading and listening comprehension, speaking, and writing. They wanted to use appropriate verbal and nonverbal behavior and strategies to communicate in Spanish. After the first SVE session, Student 8 wrote, “it is making practicing Spanish a lot more fun!” There was considerable growth in the students’ written Spanish as well, as evidenced through their Padlet comments and summative assessments. Students reflected on how eective communication can support or hinder understanding in a global, interdependent world. Student 4 said “this project was really important because it helped us to improve our language skills by talking with them. And so while we’re learning about these interesting topics, we’re also working on improving our language.”FINDING 4: Virtual Exchange benets from asynchronous sessions to build rapport. Before the first SVE, the students voiced their nervousness about communicating with the native speakers in Spain. To decrease anxiety and make for a more equitable exchange due to time zones, the students engaged in a number of AVEs via Padlet and Flip. This increased their excitement about the project and boosted their confidence. The girls joyfully exchanged recorded videos introducing themselves, and commented on how fun it was. Communication, for the girls, was more meaningful and productive when they felt they personally connected with their partners.FINDING 5: Virtual Exchange requires attentive adult facilitation. During the SVEs, the students were more nervous and serious. It was important to always begin with an icebreaker. At times, I intervened, prompting students to participate in the conversation. The observer of the second SVE noted that it was easy to identify the leaders and that “Teacher intervention and teacher prompts seem to enhance the experience. Each time Dr. Brenot stepped in, more students participated in her class.” More teacher involvement on the VE partner side could mitigate this. Student 3 shared that before our VEs, her classmates would discuss things in class, but that she was “always the one who was listening.” VE pushed her to speak and to “express my own opinion on lots of topics...”FINDING 6: Virtual Exchange can prompt problem solving and community engagement in studentsMoved by their discovery of the rates of hunger in Monterey County, Barcelona, and Toronto, the students researched ways they could help to address hunger by collaborating with their partners during the second SVE. The observer wrote that Student 4 presented “the idea of volunteering with organizations that address this issue” and “asked all the students on her screen what they thought about her idea.” Communication led to collaboration, which led to problem-solving. At the project’s close, Student 7 stated that the VEs inspired her to do community service: “after our virtual exchange, I’ve become more interested in talking about it with my family and recently volunteering at school when we went to Brighter Bites and packaged over 1,000 boxes for communities.” Student 5 passionately declared that “everyone needs to do their part. And everyone in the community has to contribute something.” Identifying and creating opportunities to address hunger boosted the students’ community engagement and, consequently, improved conditions on the Monterey Peninsula.21FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORG

CONCLUSION: Opportunities and ChallengesThe results from this study show that VE developed global competence by connecting girls with international peers, prompting them to investigate the world, recognize perspectives, communicate ideas, and take action to improve conditions for collective well-being; this was in line with previous scholarship. It also showed that Spanish lingua franca VE advances students’ FL Spanish language skills. By homing in on UN SDG #2 and pandemic-induced hunger, my students came to understand some of the inequities that cause hunger in dierent locations on the globe and gained greater empathy for those suering from food insecurity. Deep learning took place because of the VEs.Challenges, though not insurmountable, were encountered. VE requires attentive adult intervention and planning. It is important that VEs be led by a teacher who is not only well-versed in teaching for global competence but is also technologically skilled and can help students contextualize and process the lessons learned through VE. It is also important to balance asynchronous and synchronous activities for equitable exchange, as noted in the Stevens Initiative’s 2022 Virtual Exchange Impact and Learning Report (2023). It is beneficial to start a VE unit with several AVEs so that students’ get acquainted with each other asynchronously without the pressure of live video conversation.Girls want to be able to connect and understand each other. Cultural dierences, for the most part, piqued my students’ interest and motivated them to learn about their partners’ cultures so they could better understand them. Perfectionism, however, sometimes inhibited the SVEs because my students wanted to communicate accurately in Spanish, especially with their Spanish peers. Preparing students beforehand for SVEs by having them research a topic in the lingua franca, learn relevant vocabulary, and think out questions and potential answers to their questions can help them overcome any reticence to speak. Conducting more SVEs with the same group of international peers would likely increase the students’ comfort level and build deeper relationships, allowing for richer discussions, debates, and collaboration.VIRTUAL EXCHANGEOverall, VE is well worth the effort, despite the time and preparation it requires. Adaptability and exibility on the part of educators and students are essential, as is support from administrators. Any school whose mission is to provide intentional, equitable, curriculum-driven global education would be wise to establish and maintain VEs. When used effectively with a lingua franca approach, it demonstrably develops students’ global competence, boosts FL uency and digital skills, and breaks down international and cultural divides. The adoption of VE as a curricular enhancement serves to globalize curriculum and classrooms, helping to create more internationally minded environments so that schools can answer the pressing call to produce globally competent citizens and leaders. ■INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 0622

23FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGGEBG GLOBAL SUMMIT ON CLIMATE EDUCATIONPAGE 23 CONNECTIONS MAGAZINETop right: Former GEBG Board Member, Tené Howard of the Sadie Nash Leadership Project, facilitates a discussion with keynote speaker Karenna Gore of the Center for Earth Ethics at Union Theological Seminary. Far left: 160 educators gathered at Teachers College on Columbia University's campus in New York to discuss, learn, and share about educating global citizens in an era of climate change.

24INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06Benchmarking Data2022-23 NAIS-GEBG GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT SURVEY RESULTSParticipating School DemographicsCollecting, analyzing, and sharing data is a hallmark of the Global Education Benchmark Group. The data reflects the ways schools are engaging with the world through global curriculum, experiences, partnerships, and more. This year, GEBG partnered with the National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) to look at wider trends in the field of global education. Schools had the option to skip individual questions throughout the survey aecting response sizes and potentially altering statistical significance. Responses sizes may vary to some degree by question.In which division(s) is/ are global education active at your school?HIGHSCHOOLMIDDLESCHOOLPRIMARYSCHOOL44.6%83.2%65.5%What is the size of your school?UNDER200 STUDENTSBETWEEN 200-300 STUDENTSBETWEEN 301-500 STUDENTSBETWEEN 501-700 STUDENTSOVER 700 STUDENTS3610510264153ANALYSIS PROVIDED BY DANNY SCHIFF AP Statistics Teacher, 'Iolani School, Hawaii, USA494schools from Canada and United Statescountries are represented in the dataare day schools are co-educational51.2% NAIS members only, 5.1% GEBG members only, 43.3% Both NAIS and GEBG306 high schools (9-12), 241 middle schools (6-8), and 164 primary schools (Pre-K-5)3090% 78% 85%schools participated

25FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGBENCHMARKING DATAWhy Schools Offer Global EducationWhat are the primary reasons why your school oers a global education program?Among both NAIS and GEBG schools, there are a variety of reasons why schools pursue global education. It is the hope of NAIS and GEBG that this survey might provide some perspective and a guide for programs. It is the hope that this data may further the dialogue for potential positive effects for students, teachers, administration, and our global partners when building or developing programs.Note: Other reasons given were to support linguistic and cultural uency, building global partnerships, and faith based initiatives.TO ENGAGESTUDENTS IN GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP ANDINTERCULTURALLEARNINGTO TEACHKNOWLEDGE, SKILLS AND PERSPECTIVESRELATED TO GLOBALEDUCATIONTO FULFILL THE SCHOOL’SMISSIONTO DIFFERENTIATESCHOOL FROM OTHER SCHOOLS IN THE AREATO IMPROVE COLLEGE ACCEPTANCE RATES79.0%74.9%56.4%21.0%8.8%

26INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06BENCHMARKING DATAGlobal Learning and EngagementMost commonly reported global offerings at participating school is 2022-2023.World (modern and classical) language requirement in high school 79%Globally focused clubs (ex: Model UN etc.) 73.1%Regular and ongoing global or cultural events on campus 69.3%World (modern and classical) language requirement in middle school 69%Assemblies or speakers on global current events or issues 67.9%Opportunities provided to students to engage locally with global issues (e.g. climate change, income inequality, hunger etc.) with various communities and partners67.4%High school elective classes with a global focus 65.2%World (modern and classical) language requirement in primary school 48%Globally focused community engagement for students 46.6%School meeting place for students to discuss global issues and events 45.6%Course(s) with a domestic travel (overnight) component 41.5%Course(s) with a travel abroad component 39.1%Student leadership positions or opportunities related to global education 38%Partnered program with other schools for student virtual conversations or dialogues 35.9%

27FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGBENCHMARKING DATAGlobal Learning and EngagementMost common globally focused courses beyond world language.Note: 7% of schools did not require students to take any globally focused course beyond world languages.Note: English as an additional language, German, Japanese, Greek, Russian are the next most common languages offered.WORLD HISTORYWORLD LITERATUREWORLD RELIGIONSGLOBAL ISSUESENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE71%40%26%25%25%Most common languages taught per division.SPANISHFRENCHCHINESE(MANDARIN)HIGH SCHOOL MIDDLE SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL83%74%52%67%52%22%55%34%11%

28INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06BENCHMARKING DATABenchmarking GEBG Member SchoolsHere are some of the areas where we saw the greatest difference between the offerings at GEBG member schools and non GEBG member schoolsHIGH SCHOOL ELECTIVE CLASSES WITH A GLOBAL FOCUS73%52%29%11%40%28%GLOBAL CERTIFICATE OR DIPLOMA BEYOND GENERAL GRADUATION REQUIREMENTSPARTNERED PROGRAM WITH SCHOOLS FOR VIRTUAL CONVERSATIONS/DISCUSSIONS SCHOOL MEETING PLACE FOR STUDENTS TO DISCUSS GLOBAL ISSUES AND EVENTS51%38%48%20%40%24%STUDENT LEADERSHIP POSITIONS RELATED TO GLOBAL EDUCATIONINFORMATION PROVIDED TO STUDENTS INTERESTED IN TAKING A GAP YEARGEBG SCHOOLS NON-GEBG SCHOOLS

29FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGBENCHMARKING DATALeadership and AdministrationGlobal education is largely comprised of both on-campus curricular opportunities and student travel programs.GEBG and NAIS schools report oering of elective classes (64%), global diplomas (23%), globally focused student leadership opportunities (38%), as well as permitting semester-long (38%) and year-long (31%) study programs away from sending schools. The results of this year’s data shows how schools are finding ways to engage in global education on campus throughout the school year.Global education is included in the school’s mission statement or other guiding documentsSchool’s strategic plan makes a commitment to global educationSchool has developed partners for community engagement opportunities The most commonly reported global education partnerships or structures at participating schools52%52%56%School hosts international students as part of a short-term exchangeSchool enrolls matriculating international students43%46%94%of schools offered overnight travel programs lasting 2 or more days, international or domestic.51%of schools support professional learning on bringing global perspectives into the curriculum.What is the administrative structure of global education and activities at your school?Did your school assess global initiatives for impact?74%29%18%43%Did you school engage in strategic planning for global education?Is the lead administrator for global programs a member of senior administration?Are there opportunities for faculty to engage in professional learning abroad?GLOBAL EDUCATION STAFF OR OFFICETEACHERS DEVELOP AND RUN THEIR OWN PROGRAMS MULTIPLE OFFICES ADMINISTER GLOBAL EDUCATION AMONG OTHER FUNCTIONS PART TIME SUPPORT STAFFNO OFFICE OR STAFF PERSON37%56%27%17%8%YESYESYESYES

30INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06BENCHMARKING DATAStudent Travel94% of all schools surveyed offered overnight travel opportunities for students, either domestic or international. 57% of high schools offer between 1 and 4 international travel programs per year, compared to 49% of middle schools which do not offer overnight travel programs.Number of school sponsored international trips oered in high school.Number of school sponsored international trips oered in middle schoolSchools oering travel programs (for 2 nights or more) by division.Did your school observe disproportionately low participation by any of the following demographic groups in student travel programs?HIGHSCHOOLMIDDLESCHOOLPRIMARYSCHOOL75.9%68.0%35.6%60.5%3.9%Students who identify as female2%12%10%Students who identify as maleStudents of color22.4%INTERNATIONALDOMESTIC0 1-2 3-4 5-6 7-8 9-10 11+15.6%26.4%23.9%14.3%15.6%4.6%2.6%48.9%42.1%5.9%3.0%0 1-2 3-4 5-6

31FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORGHOMESTAY47%ATHLETIC COMPETITIONS37%PERFORMING OR VISUAL ARTS37%SUSTAINABILITY OR CLIMATE CHANGE35%BENCHMARKING DATAReflected in this year’s travel program data are a variety of program components and themes related to the realities of bridging a growing demand for global programs, may schools doing so with limited funding, few experienced teachers, and not enough time. A majority of schools are completing a pre-departure curriculum or series of meetings (90.1%) as well as post travel meetings to continue with learning and reflection (67.2%). A majority of schools engage in community engagement and service learning (54.2%) while nearly all schools take advantage of cultural learning opportunities during travel (83.3%).Most visited international countries (excluding USA)1. France 111 schools2. Spain 97 schools3. United Kingdom 80 schools4. Costa Rica 79 schools5. Germany 46 schools6. Ecuador 26 schools7. Iceland 22 schools8. Guatemala 18 schools9. Switzerland 18 schools 10. Bahamas 17 schoolsWhat types of overnight travel programs were oered by your school?INTRODUCTORY CULTURAL TOUROTHER: MODEL UNITED NATIONS66%OUTDOOR EDUCATION53%LANGUAGE IMMERSION51%COMMUNITYENGAGEMENT48%Work with 3rd party providersA formalized process for assessing risk for travel programsSome restrictions on cell phones/ devicesFormalized chaperone/leader trainingThe most commonly reported global education partnerships or structures at participating schools44%70% 59% 61%

32INTERCONNECTED / VOLUME 06Funding and BudgetData shows a wide discrepancy in budget, finances, and resources among the nearly 500 schools participating in this survey.Data shows that some schools have funding for travel, teacher stipends, and financial aid through either endowments or operating budget, while many schools pass along the costs to participants directly. Because there are many types of models, schools can rest assured that no one program’s design is a statistical outlier.What is the funding for global education in USD (excluding salaries and financial aid)?EXCEEDS $75,OOOBETWEEN $25,000-$75,000BETWEEN $1-$25,000THERE'S NO BUDGETWhat financial aid is available for student travel?BENCHMARKING DATA$1,000-2,000 MEDIAN COST PER MIDDLE AND HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT FOR DOMESTIC TRAVEL PROGRAM18% 18%35%29%SCHOOL PROVIDES A LIMITED AMOUNT OF FINANCIAL AID FOR TRAVELSCHOOL MEETS ALL NEED FOR FINANCIAL AID FOR TRAVEL16%48%$3,000-4,000 MEDIAN COST PER MIDDLE AND HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT FOR INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL PROGRAM (EXCLUDING FLIGHTS)

In the post pandemic climate, this survey demonstrates that opportunities abound, however GEBG and NAIS would be remiss to not make mention of the challenges schools are facing in the field of global education and travel. Challenges range from lack of buy-in from school leadership (14%), low student interest (11%), and limited buy-in from parents (7%). These smaller proportions reflect a majority of support across invested constituents, although the realities of any lack of support can be a debilitating challenge for the success of a program. With two significant world wars and many schools still feeling the eects of the COVID pandemic, global student travel has significant challenges in the state of the world.What are the biggest challenges your school faces to fully implement global education initiatives for large and small schools?BENCHMARKING DATASCHOOLS UNDER 200 STUDENTS SCHOOLS OVER 700 STUDENTSCOMPETING SCHOOL PRIORITIES46%52%60%41%38%43%LACK OF FINANCIAL RESOURCESINSUFFICIENT STAFFLACK OF CLEAR GOALS FOR THE PROGRAM46%20%2023 Annual Conference in DCGEBG Action Research Fellows Share their research at the 2023 Global Educators Conference in DC.GEBG Board Member Dr. Karina Baum with Guest Speaker Dr. Veronica Boix-Mansilla at the 2023 Global Educators Conference in DC.Panelists from the DEIB and Global Education Panel at the 2023 GEBG Global Educators Conference in DC.33FIND US AT WWW.GEBG.ORG