Return to flip book view

GIRLS AS GLOBAL CITIZENSA Moral Responsibility for EducatorsIMPACT OF GLOBAL EDUCATION PROGRAMS OVER TIMECOVID’S IMPACTS ON TRAVEL RISK MANAGEMENT

Academy of Notre Dame de Namur, Villanova, PA, USAAcademy of the Sacred Heart, New Orleans, LA, USAAgnes Irwin School (The), Bryn Mawr, PA, USAAIM Academy, Conshohocken, PA, USAAll Saints Academy, Winter Haven, FL, USAAll Saints Episcopal School, Fort Worth, TX, USAAltamont School (The), Birmingham, AL, USAAmerican School in London (The), London, United KingdomAmerican School of The Hague, Wassenaar, NetherlandsAndover High School, Andover, MA, USAAppleby College, Oakville, ON, CanadaArcher School for Girls (The), Los Angeles, CA, USAAshbury College, Ottawa, ON, CanadaAshley Hall, Charleston, SC, USAAspen Country Day School, Aspen, CO, USAAthenian School, Danville, CA, USAAthens Academy, Athens, GA, USAAtlanta Girls’ School, Atlanta, GA, USAAugusta Preparatory Day School, Martinez, GA, USAAvenues: The World School, New York, NY, USAAwty International School, Houston, TX, USABattle Ground Academy, Franklin, TN, USABaylor School, Chattanooga, TN, USABelmont Hill School, Belmont, MA, USABergen County Academies, Hackensack, NJ, USABerkeley Carroll School (The), Brooklyn, NY, USABerkeley Preparatory School, Tampa, FL, USABerkshire School, Sheffield, MA, USABesant Hill School of Happy Valley, Ojai, CA, USABishop’s School (The), La Jolla, CA, USABlair Academy, Blairstown, NJ, USABlake School (The), Hopkins, MN, USABolles School (The), Jacksonville, FL, USABrewster Academy, Wolfeboro, NH, USABrunswick School, Greenwich, CT, USABryn Mawr School (The), Baltimore, MD, USABuckingham Browne & Nichols School, Cambridge, MA, USABuckingham Friends School, Lahaska, PA, USABuckley School (The), Sherman Oaks, CA, USABullis School, Potomac, MD, USABush School, Seattle, WA, USACalhoun School (The), New York, NY, USACannon School, Concord, NC, USACape Henry Collegiate School, Virginia Beach, VA, USACarolina Friends School, Durham, NC, USACastilleja School, Palo Alto, CA, USAChadwick International, Songdo-dong, South KoreaChadwick School, Palos Verdes Peninsula, CA, USAChaminade College Preparatory School, St. Louis, MO, USACharlotte Country Day School, Charlotte, NC, USACharlotte Latin School, Charlotte, NC, USAChatham Hall, Chatham, VA, USAChinese American International School (The), San Francisco, CA, USAChinese International School, Braemar Hill, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaChinese Language Institute (CLI), Colorado Springs, CO, USAChoate Rosemary Hall, Wallingford, CT, USAChristchurch School, Christchurch, VA, USACincinnati Country Day School, Cincinnati, OH, USACollegiate School, Richmond, VA, USAColorado Academy, Denver, CO, USAColorado Springs School (The), Colorado Springs, CO, USAColumbus Academy, Gahanna, OH, USACommunity School of Naples, Naples, FL, USAConvent & Stuart Hall, San Francisco, CA, USACrystal Springs Uplands School, Hillsborough, CA, USADalton School (The), New York, NY, USADana Hall School, Wellesley, MA, USADe Smet Jesuit High School, Saint Louis, MO, USADeerfield Academy, Deerfield, MA, USADelbarton School, Morristown, NJ, USADerryfield School (The), Manchester, NH, USADetroit Country Day School, Beverly Hills, MI, USADurham Academy, Durham, NC, USADwight School, New York, NY, USAEastside Preparatory School, Kirkland, WA, USAEllis School (The), Pittsburgh, PA, USAEmma Willard School, Troy, NY, USAEpiphany School of Global Studies (The), New Bern, NC, USAEpiscopal Collegiate School, Little Rock, AR, USAEpiscopal High School, Alexandria, VA, USAEpiscopal School of Baton Rouge, Baton Rouge, LA, USAEpiscopal School of Dallas, Dallas, TX, USAEpiscopal School of Jacksonville, Jacksonville, FL, USAErmitage International School of France, Maisons Laffitte, FranceEthical Culture Fieldston School, Bronx, NY, USAFelsted School, Essex, EnglandFenn School (The), Concord, MA, USAFlintridge Preparatory School, La Canada, CA, USAFort Worth Country Day, Fort Worth, TX, USAFountain Valley School of Colorado, Colorado Springs, CO, USAFrancis Parker School, San Diego, CA, USAFranklin Road Academy, Nashville, TN, USAFrench American International School, San Francisco, CA, USAFriends Seminary, New York, NY, USAGeorge School, Newtown, PA, USAGeorge Walton Academy, Monroe, GA, USAGermantown Friends School, Philadelphia, PA, USAGill St. Bernard’s School, Gladstone, NJ, USAGilman School, Baltimore, MD, USAGilmour Academy, Gates Mills, OH, USAGLOBE Academy (The), Atlanta, GA, USAGood Shepherd Episcopal School, Dallas, TX, USAGould Academy, Bethel, ME, USAGrace Church School, New York, NY, USAGredos San Diego (GSD) Schools, Madrid, SpainGreens Farms Academy, Greens Farms, CT, USAGreensboro Day School, Greensboro, NC, USAGreenwich Academy, Greenwich, CT, USAGroton School, Groton, MA, USAHackley School, Tarrytown, NY, USAHarker School (The), San Jose, CA, USAHarpeth Hall School, Nashville, TN, USAHarvard-Westlake School, Studio City, CA, USAHathaway Brown School, Shaker Heights, OH, USAHaverford School (The), Haverford, PA, USAHawken School, Gates Mills, OH, USAHead-Royce School, Oakland, CA, USAHerlufsholm Skole og Gods, Næstved, DenmarkHewitt School (The), New York, NY, USAHill School (The), Pottstown, PA, USAHockaday School (The), Dallas, TX, USAHolton-Arms School, Bethesda, MD, USAHoly Innocents’ Episcopal School, Atlanta, GA, USAHotchkiss School (The), Lakeville, CT, USAHun School of Princeton (The), Princeton, NJ, USAHutchison School, Memphis, TN, USAIsidore Newman School, New Orleans, LA, USAIvanhoe Grammar School, Ivanhoe, Melbourne, VIC, AustraliaJohn Burroughs School, St. Louis, MO, USAKent Denver School, Englewood, CO, USAKent Place School, Summit, NJ, USAKents Hill School, Kents Hill, ME, USAKentucky Country Day School, Louisville, KY, USAKeystone Academy, Beijing, ChinaKing School, Stamford, CT, USAKing’s Academy, Madaba, JordanLa Jolla Coutry Day School, La Jolla, CA, USALab School of Washington (The), Washington, DC, USALake Forest Academy, Lake Forest, IL, USALake Oconee Academy, Greensboro, GA, USALakeside School, Seattle, WA, USALancaster Country Day School, Lancaster, PA, USALaurel School, Shaker Heights, OH, USALausanne Collegiate School, Memphis, TN, USALawrence Woodmere Academy, Woodmere, NY, USALawrenceville School (The), Princeton , NJ, USALoomis Chaffee School, Windsor, CT, USALouisville Collegiate School, Louisville, KY, USALovett School, Atlanta, GA, USALower Canada College, Montréal, Québec, CanadaMadeira School (The), McLean, VA, USAMarist School, Atlanta, GA, USAMary Institute and Saint Louis Country Day School , St. Louis, MO, USAMarymount School of New York, New York, NY, USAMasters School (The), Dobbs Ferry, NY, USAMcDonogh School, Owings Mills, MD, USAMenlo School, Atherton, CA, USAMercersburg Academy, Mercersburg, PA, USAMiami Country Day School, Miami, FL, USAMiddlesex School, Concord, MA, USAMiss Porter’s School, Farmington, CT, USAMontclair Kimberley Academy, Montclair, NJ, USAMoravian Academy, Bethlehem, PA, USAMorgan Park Academy, Chicago, IL, USAMorristown Beard School, Morristown, NJ, USAMoses Brown School, Providence, RI, USAMount Vernon Presbyterian School, Atlanta, GA, USANational Cathedral School, Washington, DC, USANew Canaan Country School, New Canaan, CT, USANew England Innovation Academy, Mystic, CT, USANew Hampton School, New Hampton, NH, USANewton Country Day School of the Sacred Heart, Newton, MA, USANightingale-Bamford School, New York, NY, USANoble and Greenough School, Dedham, MA, USANorfolk Academy, Norfolk, VA, USANorth Cross School, Roanoke, VA, USANorth Shore Country Day School, Winnetka, IL, USANorthwest School (The), Seattle, WA, USANorthwood School, Lake Placid, NY, USAOaks Christian School, Westlake Village, CA, USAOakwood School, North Hollywood, CA, USAOld Trail School, Bath, OH, USAOverlake School (The), Redmond, WA, USAPace Academy, Atlanta, GA, USAPacific Ridge School, Carlsbad, CA, USAPacker Collegiate Institute, Brooklyn, NY, USAPalmer Trinity School, Miami, FL, USAPeddie School, Hightstown, NJ, USAPennington School (The), Pennington, NJ, USAPhillips Academy Andover, Andover, MA, USAPhillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH, USAPickering College, Newmarket, ON, CanadaPine Crest School, Boca Raton, FL, USAPingry School (The), Bernards, NJ, USAPolytechnic School, Pasadena, CA, USAPomfret School, Pomfret, CT, USAPorter-Gaud School, Charleston, SC, USAPrinceton Day School, Princeton, NJ, USAProvidence Day School, Charlotte, NC, USAPunahou School, Honolulu, HI, USARansom Everglades School, Miami, FL, USARavenscroft School, Raleigh, NC, USARiverdale Country School, Bronx, NY, USARivers School (The), Weston, MA, USARobert College, Kuruçeşme Cad No. 87, Beşiktaş, TurkeyRochambeau, the French International School, Bethesda, MD, USARutgers Preparatory School, Somerset, NJ, USARye Country Day School, Rye, NY, USASacred Heart Preparatory, Atherton, CA, USASage Hill School, Newport Beach, CA, USASaint Andrew’s School, Boca Raton, FL, USASaint Catherine’s School, Richmond, VA, USASaint David’s School, New York, NY, USASaint Edward’s School, Vero Beach, FL, USASaint Joseph Academy, Cleveland, OH, USASaint Thomas Academy, Mendota Heights, MN, USASaint-Denis International School, Loches, FranceSanta Catalina School, Monterey, CA, USAScarsdale High School, Scarsdale, NY, USASchool Year Abroad, North Andover, MA, USASequoyah School, Pasadena, CA, USASewickley Academy, Sewickley, PA, USAShady Side Academy, Pittsburgh, PA, USAShanghai Qingpu World Foreign Language School, Shanghai, ChinaShipley School (The), Bryn Mawr, PA, USASidwell Friends School, Washington, DC, USASilicon Valley International School, Palo Alto, CA, USASolebury School, New Hope, PA, USASonoma Academy, Santa Rosa, CA, USASpringside Chestnut Hill Academy, Philadelphia, PA, USASt. Albans School, Washington, DC, USASt. Andrew’s Episcopal School (Ridgeland, MS), Ridgeland, MS, USASt. Andrew’s Schools (The), Honolulu, HI, USASt. Christopher’s School, Richmond, VA, USASt. George’s School, Middletown, RI, USASt. Joseph’s Academy, St. Louis, MO, USASt. Louis University High School, St. Louis, MO, USASt. Luke’s School, New Canaan, CT, USASt. Mark’s School, Southborough, MA, USASt. Mary’s Episcopal Day School, Tampa, FL, USASt. Mary’s Episcopal School, Memphis, TN, USASt. Michael’s Catholic Academy, Austin, TX, USASt. Michaels University School, Victoria, BC, CanadaSt. Paul’s School (ES), Barcelona, SpainSt. Paul’s School (SPS), Concord, NH, USASt. Paul’s Schools (The), Brooklandville, MD, USASt. Stephen’s Episcopal School, West Bradenton, FL, USASt. Stephens and St. Agnes School, Alexandria, VA, USASt. Teresa’s Academy, Kansas City, MO, USASt. Thomas School, Medina, WA, USASteward School (The), Henrico, VA, USAStiftung Louisenlund, Gueby, Schleswig-Holstein, GermanyStone Ridge School of the Sacred Heart, Bethesda, MD, USATabor Academy, Marion, MA, USATampa Preparatory School, Tampa, FL, USATASIS The American School in Switzerland, 6926 Montagnola, SwitzerlandThacher School (The), Ojai, CA, USATower Hill School, Wilmington, DE, USATransylvania College, Cluj Napoca, RomaniaTrevor Day School, New York, NY, USATrinity Hall, Tinton Falls, NJ, USATrinity School NYC, New York, NY, USATrinity Valley School, Fort Worth, TX, USATurning Point School, Culver City, CA, USAUniversity High School of Indiana, Carmel, IN, USAUniversity Prep, Seattle, WA, USAUniversity School, Hunting Valley, OH, USAUrsuline Academy, Wilmington, DE, USAUrsuline Academy of Dallas, Dallas, TX, USAUrsuline School (The), New Rochelle, NY, USAVirginia Episcopal School, Lynchburg, VA, USAVisitation Academy, Saint Louis, MO, USAVisitation School, Mendota Heights, MN, USAVistamar School, El Segundo, CA, USAWardlaw Hartridge School, Edison, NJ, USAWaterford School, Sandy, UT, USAWebb School of Knoxville, Knoxville, TN, USAWellington College, Crowthorne, Berkshire, United KingdomWellington School (The), Columbus, OH, USAWestminster Schools (The), Atlanta, GA, USAWestridge School for Girls, Pasadena, CA, USAWesttown School, West Chester, PA, USAWheeler School (The), Providence, RI, USAWilbraham & Monson Academy, Wilbraham, MA, USAWilliam Penn Charter School, Philadelphia, PA, USAWilliams School (The), Norfolk, VA, USAWilmington Friends School, Wilmington, DE, USAWindward School, Los Angeles, CA, USAWoodberry Forest School, Woodberry Forest, VA, USAWoodlands Academy of the Sacred Heart, Lake Forest, IL, USAWoodward Academy, College Park, GA, USA2021 MEMBER SCHOOL LIST

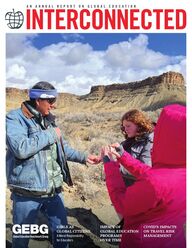

321123230262359Senior StaffClare Sisisky Executive Director Elsie Stapf Director of Operations Chad Detloff Director of Professional Learning and Curriculum2021 - 2022Board of DirectorsOFFICERSChair Joe Vogel, Old Trail SchoolSecretary Laura Appell-Warren, St. Mark’s SchoolTreasurer Wally Swanson, Wilbraham & Monson AcademyBOARD MEMBERSTrish Anderson, Pace AcademyKarina Baum, Buckingham Browne & NicholsSchoolMelissa Brown, Holton-Arms SchoolDion Crushshon, Blake SchoolNishad Das, Groton SchoolAnn Diederich, Polytechnic SchoolDaniel Emmerson, Felsted SchoolTené Howard, Sadie Nash Leadership ProjectRob McGuiness, Appleby CollegeManjula Salomon, Palmer Trinity SchoolAric Visser, Baserria Institute of International and Intercultural EducationDebra Wilson, Southern Association of Independent SchoolsABOUT GEBGThe Global Education Benchmark Group supports schools as they prepare students for a culturally diverse and rapidly changing world. We are the leading K-12 global education organization that provides professional learning on model practices and shares data and resources for schools as they develop teachers and students with the intercultural competencies to embrace and thrive in our interconnected world.Student Perspectives on the PandemicVirtual Exchange Eectively Fosters Global Competence for High School StudentsLearning from Alumni: Impact of Global Education Programs Over TimeBenchmarks In Global EducationSupporting International Students Through an Equity LensCOVID’s Impacts on Travel Risk Management Expert Perspectives on Considerations as Students Return to the FieldOn the Same Page Assessing Faculty Definitions of Global Education LanguageRaising a Brave New WorldGirls as Global Citizens A Moral Responsibility for Educators3407 S. Jeerson Ave., Suite 71 St. Louis, MO 63118@gebgcommunicate2394043Perspective Letter from our Editor2021 Financial and Impact ReportGET Prize Award WinnersGlobal Educator Profiles Jessica YonzonGlen Turf(888) 291 GEBG (4324) www.gebg.orgTABLE OF CONTENTSSpring 2022GEBG Board April 2022ABOUT THE COVER Pace Academy students learn from a community educator in Navajo Nation in partnership with Deer Hill Expeditions. Magazine Designed by Brand Poets

THESE PAST TWO YEARS have given all of us in global education the chance to consider the challenges and opportunities of our field, whether we wanted that chance or not. This year’s magazine is full of reflections and evaluations that demonstrate how global educators strove to make the most of the shifting landscape of global education, and what they hope for our future. The GEBG community works to support and share with each other both our exemplary models as well as our challenges and questions. In this year’s Interconnected, we hear from two long-time community members about their thought-partnership as they wrestled with change, a dynamic exchange that I know was experienced by partners in our community. We hear from expert voices on the new risk management landscape. We share photos of our students engaging in local learning with a global focus. This year’s issue focuses, however, on emerging research and ways that our community has used the past two years to engage in evaluation or assessment. Understanding the impact of our global education initiatives is a challenging and complex endeavor, and we hope these research findings and models can support schools as they make the case of global education at their schools. But this research can also support our work to continually improve our programs, guiding the design of our learning experiences and curriculum towards the best possible outcomes for our students, colleagues, and partners while more adeptly mitigating any unintended consequences. These past two years, we have seen and felt the need for deep understanding of how our world is interconnected and how our actions can have consequences beyond our campuses. When I see so many working to tear each other down, when I witness the horrors of conflicts in multiple locations around the world, or when I hear the continued call for more significant action to fight climate change; I become even more committed to global education than before. We hope that this year’s Interconnected can support your eorts, renew your commitment, and oer a sense of community as we all work together to improve our field, year after year. CLARE SISISKY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF csisisky@gebg.org | @gebgcommunicateLETTER FROM OUR EDITORPERSPECTIVE

KEREM BABAOĞLULevel 9, Robert College (Istanbul, Turkey)Grade 11, Wardlaw+Hartridge (New Jersey, USA)NAISCHA PURION THE PANDEMIC STUDENT PERSPECTIVES WHAT HAVE YOU FOUND MOST DIFFICULT ABOUT THE PANDEMIC?KEREM BABAOĞLU (KB): The most dicult thing about the pandemic is the feeling of isolation from the world I used to belong to. We were stuck in our houses without seeing each other. Of course there were communication apps, but I wasn’t a huge fan of those black boxes. And now, we are together, yet with masks. I can’t remember the last time I saw a classroom full of peers smiling together. Actually, what broke my heart most was the lack of “togetherness” the pandemic caused. I feel that we all got much lonelier than pre-pandemic times.NAISCHA PURI (NP): The pandemic has been dicult in realizing what we are missing and unable to do. It has been nearly impossible to travel to see elderly relatives, go to family member’s weddings, and loads of other family-related setbacks. While the pandemic has been hard, and these may seem like top priorities, I have been able to understand that certain “needs” hold precedence over others, and it is most important that everybody stays safe and healthy.AS EDUCATORS, we know that our students can provide us with a fresh perspective, often one with inspiring optimism and reassuring resilience. We asked two students from two dierent GEBG Schools to share some reflections on their experiences of the pandemic thus far. 3WWW.GEBG.ORG

WHAT HAS BEEN ONE POSITIVE CONSEQUENCE OF THE PANDEMIC?KB: However, there is positive stu about the pandemic like everything else. For example, I was able to be more ecient when I didn’t lose 2 hours of my day to trac. Studying from home was making it easier for me to complete my assignments. It was also quite comfortable to learn new things in a place where you feel more secure. NP: One positive consequence has been the time to self-reflect and spend time with family. Being forced to quarantine among busy and stressful work or school gave us a chance to reconnect and understand each other better. I have also been able to do some yoga, read tons of books from my “to be read” pile, try new things like instruments and food, and also develop my vinyl collection further!WHAT’S ONE WAY IN WHICH YOU FEEL YOU HAVE BEEN CHANGED AS A RESULT OF THE PANDEMIC?KB: During the pandemic days, I was prohibited from outdoor activities, so I spent most of my time with games, movies and sleep. Although the prohibitions and lockdown are somewhat over, I am a bit withdrawn from going outside. I don’t have the desire to go out, and I enjoy staying at home, watching TV, sipping coee and sleeping all day long. This is again related to losing the concept of “togetherness” and demonstrating more individualistic behaviors.NP: I feel like I am a more compassionate and thoughtful person. I try to talk less and listen more. I allow myself to actively reach into my conscience and make decisions that bring me peace and happiness in my life consistently. I am constantly growing and learning.WHAT’S ONE WAY IN WHICH YOUR PERSPECTIVE ABOUT THE WORLD HAS CHANGED AS A RESULT OF THE PANDEMIC?KB: I sense that the world changed similarly to how I was aected by the pandemic. While the negative repercussions of the pandemic are clear, all of us had dierent chances to discover ourselves and our secret interests. Being aware of ourselves is an essential part of life, and the pandemic helped us to recover some of this self-knowledge.NP: We are all human; I think it is easy to forget that. As I mentioned, I have tried to practice more compassion and understanding. I am trying to be more aware of what is going around me and learn the significance of being part of a community.WHAT’S ONE LESSON YOU HOPE FUTURE GENERATIONS WILL LEARN FROM THE PANDEMIC?KB: Create a connection with yourself and your surroundings. Observe, notice, appreciate. Value the moments you create and be mindful of everything going on around and inside you. NP: I hope future generations understand the value of getting through something together. The more we wore our masks together, quarantined together, helped each other, taught each other, and cared about each other, the more smoothly we were able to get through some of the roughest times. 4 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

Raising a Brave New Worldby Manjula Salomon and Daniel EmmersonWe began to consider a collaborative article when we met for coee during a conference in Cape Town at some point in 2017. We were in South Africa to support our students in an experience that would hopefully shape the rest of their lives at our respective schools and beyond that. Our idea at the time was to write a joint account of the state of play in global education from our unique perspectives. Our idea at the time was to write a joint account of the state of play in global education from our unique perspectives, though each time we put pen to paper, the state of play we were attempting to document began to unravel. By the time our article took shape in March 2020, the world was in such a state of flux that it seemed impossible to pin any of our ideas down. However, over online conversations and revised drafts we have conjured a reflection concerning what we had, what we wanted, what we got, and where we need to go next—a mere distillation of research, conversations, and ideas as they stand now, and as we continue to discuss as thought partners the possibilities of raising a brave newworld.RALPH WALDO EMERSONManjula Salomon and Daniel Emmerson reunite in person at the GEBG Annual Conference in April 2022Life is a succession of lessons which must be lived to be understood.” 5WWW.GEBG.ORG

1WHAT WE HAD“No one’s words, Proust’s included, could bring back to life their warm fragrance mixed with the scents of the winter rain of California and the wet eucalyptus leaves. You owe us an invention to immortalize scents, Mr. Edison. Without that our memory is incomplete.” YIYUN LEE, Where Reasons EndHaving worked in Global Education for years, it is intriguing to consider the way that our work is defined. The practical components are broken down to things like curriculum design, international partnerships, events management, leading overseas travel programs, facilitating student exchanges, etc. But the ‘why’ for each of these areas is where that conversation becomes more interesting: to develop cultural empathy and understanding in our students (Lewis, 2018), to assist in developing collaborative practice (Markowitz, et al., 2003), and to engage young minds curious for fresh and creative perspectives (Martin, et al., 2014). All of these things remain imperative if we wish to overcome cultural isolation, polarization or even fascism in the future (Vivarelli, 1991), but the practical ways in which each of these virtues were achieved in the past had both positive and negativerepercussions. In a world prior to COVID-19, the majority of the aforementioned benefits were achieved by being in physical proximity with another individual or group, which allowed for closer bonds to be created through eye contact (Argyle and Dean, 1965), touch (Rovers, et al., 2017) and social rituals such as sharing a meal (Davies, 2019), dancing (Bergmann, 1995) or even negotiating desk space in a library (Yerkey, 1980). There was a reason that in-person experiences generated such close bonds between people of dierent cultures on trips such as the one that we took to South Africa: they existed as real world experiences that were ingrained in memories through combining immediate senses (Baddeley, 2001) like the way our feet feel after a long hike, our taste buds tingle after a new culinary experience, the smell of an overpopulated dorm room or a particular perfume or cologne that sends butterflies around the stomach (Almagor, 1990). Indeed, the power of proximity can go both ways, and it’s when looking at the negative implications that its impact can be further understood, as Min Yin Lee put it in her novel, Pachinko, “living every day in the presence of those who refuse to acknowledge your humanity takes great courage” (Lee, 2017); proximity to others amplifies our emotions whether we like it or not.When these experiences emerge in the context of a global student conference, they have the potential to strengthen friendships and build empathetic instincts, both of which are essential for the next generation (Sutherland, 1986). The downside to such opportunities, however, were more than apparent. The environmental impact of 1,000 people traveling to India for a conference, for instance, is substantial, regardless of what the inter-cultural benefits might be (Drake and Purvis, 2001). One can surely not counterbalance the other even with the most well calculated emissions measures in place. In addition to that, should those 1,000 participants attempt a community engagement project or service learning enterprise, the ramifications of which could be far less than pleasing? Such itineraries could be seen as superficial on one hand, while instilling a saviour complex into the minds of the next generation along with a jilted understanding of what ‘service’ constitutes on the other (Lodhia, 2016). As beneficial as the global education practices that we had in place were, we certainly required an overhaul.Did we engage with the global world wisely in our experiential education programs for our students? What were the unintended consequences of our approach and execution for our students, for our colleagues, for our partners, for our planet? 6 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

23WHAT WE WANTED“You can be from the ‘hood or the suburbs. You can be poor with no education or a college graduate. No matter your background, you can win.” LIL BPre-Covid practices required a more sustainable approach. Either through limiting air travel, with a focus on travel by train or engaging with global learning locally, or finding better ways to carbon oset (Dhanda and Murphy, 2011). We all recall the immense value of in-person interaction between students of dierent cultural backgrounds, which has arguably become more important in recent years. Solutions, therefore, pointed towards extended periods of stay in a host country, if a student was taking part in an exchange, for example, or on building local partnerships around global issues. But while reducing flights to as few as possible should have been the intention, bringing flights to absolute zero in favour of exclusively online meetings is detrimental to a well-rounded education and student growth (Schultz, et al., 2009). And yet, the environment has never been better for it (Rochard, 2020). ‘What we wanted’ involved the benefits of in-person interaction, without the detrimental impacts of environmental harm. We wanted this to be an inclusive measure, not just for those at our (independent) schools, but for all students regardless of theirbackground. What are we going to do with our philosophies of the past? Are we willing to unpack and critically examine the way we used to operate in global education, so we can build new programs that manifest new philosophies? How can we create and sustain partnerships and relationships that support these newprograms?WHAT WE’VE GOT“I feel at home in the entire world, wherever there are clouds and birds and human tears.” ROSA LUXEMBURGInstead of appreciating the benefits of a more interconnected world and learning to avoid some of the pitfalls, many of us have spent much of the last two years in an exclusively virtual environment, where opportunities to connect are plentiful, but often superficial and fleeting. Virtual exchanges require more screen time than we would have thought about encouraging prior to the pandemic (Moore, 2020); virtual conferences don’t provide the same opportunities to forge strong ties (Uzzell, 2008); and after months of online interaction there is a risk that our students’ views and opinions are becoming even more polarised (Carothers and O’Donohue, 2019). Perhaps an example as to what this might look like in practical terms can be seen in the feedback from Felsted’s Online International Summer School from 2020. 95% of the 367 students who completed the feedback survey said that their knowledge base increased during the course. However, how many students felt that the bonds they created allowed for friendships on social media and perhaps on future courses, without the possibility of them developing anything further in real life, thus becoming emotionally beneficial (Burch, 2020)?What will we learn from the global paradigm shift of the COVID-19 pandemic? Will we build a new paradigm OR seek to return to the one we knew? Are we going to hold fast to individualism and achievement as our dominant frameworks OR will we embrace collective intelligence and global competencies for tackling global challenges? Will we frame our programs as learning amongst and from equals with no thought of the subconscious hierarchies of our former service programs? WHERE WE NEED TO GO“We have made some decisions. We want to fail more, act without authority. Plus there’s something phlegmatic about the world state don’t you think?” THE KNIFEAt this stage, when so many countries around the world are contending with the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and are negotiating the learning environment of the present, 7WWW.GEBG.ORG

4predictions about the immediate future seem to change every other week. However, based on what we know about the benefits of global education in the past alongside the pitfalls of its practicalities, there is potential to create a fresh roadmap. If we are to raise a brave new world from the ashes of the past, we must learn from our mistakes and take advantage of the silver linings that have emerged throughout this process. It is possible to forge meaningful online communities with significant learning outcomes, but the emotional depth that they can create is questionable. As far as these last two years are concerned, it has been possible to create opportunities for students to connect, discuss and synergise. One of the keys to success in each of these areas, though, is the great value we have come to keenly appreciate of meeting in person. As we redesign our programs, a great deal of thought and care needs to go into evaluating and balancing the environmental impact, sustainability, and value of in-person meetings. That has to be one of our core roles as global educators in the brave new world: focusing on appreciation and measuring the value of interactions so that they can be prioritised, planned and prepared for, making this kind of learning central to our programs. We can’t go back to a world where such opportunities are not thoroughly considered and appreciated; or perhaps we can, but there is no telling where that might take us.What ethical framework will we use in making our judgments going forward? Will we think of our own safety personally and institutionally, and forget the safety of the communities we are entering? What percentage of our time is taken up by risk management concerns versus learning about the context and culture, from the community we are visiting and seeing them as our educators? Will we seek to travel to far and distant lands, neglecting the many global learning opportunities closer to home? Will global learning be for all students? Will we be on the same page as our colleagues? DR. MANJULA SALOMON is the Associate Head of School for Academics/Global Scholar in Residence, Palmer Trinity School in Florida, USA and DANIELEMMERSON is the Director of Global Education at the Felsted School in Essex, UK.

THE DEBATE HAS RAGED FOR DECADES: does one’s gender aect the way they experience education; do gender stereotypes impact educational outcomes? As an educator who has spent over four decades reviewing the literature on this debate, I admit to a bias. I have visited girls schools around the globe, witnessing first hand what happens when boys are removed from the equation in the education of girls. But this article is not an argument for educating girls separately–though I would happily make that argument any day of the week. Instead, I write on behalf of girls and what I know to be true about how they experience school. Girls as Global CitizensA MORAL RESPONSIBILITY FOR EDUCATORSwritten by Trudy HallTrudy Hall is the former Head of School at Emma Willard School and former Board President at the National Coalition for Girls SchoolsCastilleja School students removing Buelgrass, an invasive species, from Saguaro National Park after learning during Castilleja’s Global Week 2022 that this intentional cleansing helps prevent the spread of wildfires.9WWW.GEBG.ORG

TEENAGE GIRLS ARE THE NEW LEADERS OF OUR TIME…”Specifically, we know that while girls may not dier from boys on any intellectual dimension, they are influenced by societal factors in ways that impact their choices and behaviors. The goal for educators in working with girls is to empower them to move beyond insidious gender stereotypes, whether that be in assuming leadership roles or pursuing either academic or extracurricular interests. Exposing them to a world that needs their energy and their singular talent permits them to connect the dots between what they know to be their strengths and interests and thorny global challenges that need solutions. Once that intellectual and emotional connection is solid, it becomes the source of the confidence and courage needed to push through societal resistance and be themselves. For girls then, educating them toward a goal of global citizenship is an essential strategy for negotiating the tangled web of identity. Through authentic connection to and understanding of real world problems, girls can begin to see themselves as agents of good in the world, forces for positive change. They can imagine roles in which they have agency to make a dierence. Further, they can connect with others who are supportive of their emerging vision of themselves, creating a buer for those times when the naysayers of the universe push back. But that is just why connecting girls to the world is good for girls. There is more at stake for educators, as well as the rest of the world. To fully understand the imperative, let’s remind ourselves of the global reality: we need the full potential of the world’s girls to be at work if we are to make needed progress on the issues that challenge humanity. Sadly, we are currently a grand distance from gender equity on any number of statistical charts. According to UN Women, a United Nations organization that tracks global gender equity, as of September 2021, there were only 26 women Heads of State.At the pace at which that number is growing, gender equity will not be reached for another 130 years. Of 189 economies assessed in 2018, 104 economies still have laws preventing women from working in specific jobs, 59 economies have no laws on sexual harassment in the workplace, and in 18 economies, husbands can legally prevent their wives from working. And perhaps the most heartbreaking reality: according to UNESCO estimates, approximately 129 million girls are out of school, including 29 million of elementary age. Quite simply, for our world to turn better, educators around the globe are called to engage girls with this dismal state of aairs. Introducing girls to the skills needed to become agents of change in a global arena serves humanity. It isn’t just important that they understand how the world works; it is also critical to their well-being, as well as to the well-being of our planet. Whether that issue be climate change, education, health and nutrition or ensuring clean drinking water, girls can be steered to a pathway that speaks to their curiosity and sense of social justice, a pathway uniquely tailored to interests that can, over time and with support, become passions. Commitment to those passions that can, over time and with support, build the muscles needed to be brave when it matters in life. When we open the world up to girls, they become the changemakers the world needs. A pretty cool virtuous cycle. TEENAGE GIRLS ARE THE NEW LEADERS OF OUR TIME…”ANTONIO GUTERRES, SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE UN10 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

Where do we start? We start by connecting a girl to a cause. For a girl, the first step to becoming a global citizen might be as straightforward as linking to others who are leading a cause or have a need. Girls thrive when they are in relationships with people and big ideas. Research reminds us that girls spend more time supporting and nurturing others than boys do; generally speaking, they like “relating.” Girls are interested in people and their stories; they value connectedness, belonging and communication in which they feel “seen.” They want to feel as if who they are and what they do matters. Listen carefully to a girl and she will tell you what matters, what interests her, what energizes her. What makes her eyes flash with intensity? What problem is she intrigued by? Or angered by? To what degree is she intrigued by those problems? Has she thought about an action plan or is still searching to understand more about the issue? Help her find a role model. The world is oering up an important resource right now: teen girl role models. Finding a role model can provide the necessary seeds of inspiration that move her from interest to engagement. For starters, have her google “girl teen activist.” There is Greta Thunberg, of course, who became the teen voice of global change at 14. Samaira Mehta was only 11 when she launched initiatives to combat inequities in STEM education, and Sofia Scarlat, was 17 when she tackled domestic violence and human tracking. Fortunately, the list of such teen change “spark plugs” is impressively long. Girls are growing up at a time when young female activists are making a dierence in nearly every country on any issue. As the powerful quote on the UNICEF website notes: “Most girls don’t grow up in a world of opportunity; they build one.” Ensuring that girls are guided to these modern heroes helps them imagine the opportunity they want to help “build.” Teach her about the positive power of social media, the ultimate tool for impactful connection and changemaking. Yes, we all understand the devastatingly negative impact on self-esteem and body image caused by irresponsible uses of social media, so teach her about that, too. But consider that, according to Common Sense Media, 81 percent of teen females use social media, compared to 66 percent of teen males. (Boys do more gaming.) Using this resource for positive connection, impact, and outreach has become an essential global skill for girls. When interviewed on the topic, girls note the ability to build online communities eciently. They can learn about strategy, anity groups, networking, and resources in this space as they build their own action plan. Be her partner in creating a plan. Start small. Very small. Setting girls up for success includes partnering with them to create a vision for themselves and an action plan for how to get there–one step at a time. A simple first step is to send an email to a female activist she has identified. Maybe she can attend an organizational meeting of a local cause. Perhaps she does an informational interview with a local leader to hear them talk about how they got their start and what challenges they confronted. AND THEN, GET OUT OF HER WAY… As the Secretary General of the UN, Antonio Guterres noted in 2021: “Teenage girls are the new leaders of our time, creating global movements for change. They are ready for the challenge.” I would add only that they will be ready for that challenge if we, as educators, make their preparation our priority. Students at Academy of the Sacred Heart in New Orleans organizing an awareness campaign about responsibly disposing of plastic Mardi Gras beads to prevent them from clogging and polluting the waterways and Mississippi River11WWW.GEBG.ORG

Impact of Global Education Programs Over TimeLEARNING FROM ALUMNIwritten by Clare SisiskyMANY SCHOOLS HAVE BEEN DESIGNING and implementing immersive intercultural learning experiences over the last ten years, yet most of these schools have not assessed or even explored any long-term impact of these programs on their students. As we consider ways to assess the impact of global education programs, alumni are one group of stakeholders that is often overlooked—yet they perhaps can oer the most substantial insight into understanding any impact that these programs might have. There are several reasons for the lack of alumni voices in impact assessment and program evaluations, including the challenge of connecting with and gaining participation of alumni as well as designing ways to collect and analyze data from alumni. This article provides a summary of a three-year research study I conducted for my dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania in partnership with 6 GEBG member schools and 191 of their young alumni who participated in global education programs. One intention of global education programs at most GEBG member schools is to develop in students the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to thrive in their futures and to tackle the global challenges they will face, such as climate change; The term “global competence” is used to define this body of knowledge, skills, and dispositions, defined using the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) definition of global competence Students from St. Andrew’s Episcopal in Jackson, Mississippi on a Spring Break program in Engelberg, Switzerland12 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

which builds on the global competence framework of the Asia Society: “the capacity to examine local, global and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and worldviews of others, to engage in open, appropriate and eective interactions with people from dierent cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development” (OECD, 2018; Boix-Mansilla & Jackson, 2011). Specifically, my study focused on the aspects of global competence that center intercultural relationship-building. The October 2020 release of results and analysis from OECD’s first Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of global competence in 15-year-olds identified some key areas that can lead to stronger student outcomes (Schleicher, 2020). Providing students with “opportunities to relate to people from other cultures, including through international exchanges and virtual programmes” (Erasmus, 2020) was specifically outlined as one of 5 key ways that schools can successfully prepare young people to thrive as a result of global competence development. As many educators are considering ways to increase student development of global competence through various learning experiences and initiatives, this study aimed to better understand the impact over time of school-organized programs that immerse students in international contexts and relationships outside of their own self-identified culture. This study asked young alumni that engaged in these experiences during high school to report if and how the experience has lived with them since that time using the research question: How, if at all, do recent alumni feel that an immersive international high school learning experience influenced them over time, including any development of the global competencies of intercultural communication skills, perspective taking, andadaptability?Summary of Research MethodsThis was a sequential explanatory mixed-methods study with an emphasis on qualitative methods (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018), meaning that the study used both a survey and interviews to collect reflections from young alumni on any self-reported impacts of their high school global learning experience. The research design began with a quantitative survey that included an option for participants to volunteer to participate in a qualitative interview. 191 participants from 6 dierent independent schools in North America provided responses to the quantitative survey, and twenty of these participants participated in additional qualitative interviews. All participants were part of a short-term global learning program abroad that was organized by their high school, and all shared their reflections on their learning experience confidentiality. The quantitative data was analyzed to create composite scores for a participant’s current frequency of behaviors related to intercultural communication, perspective taking, and behavioral adaptability. Scores were also created for how participants see any influence of their high school global learning experience on their current frequencies of these global competence behaviors. While these scores helped to identify the extent to which students developed lasting global competencies during their travel experiences, the study emphasized qualitative data analysis (the twenty interviews) to more deeply understand how their global learning experience in high school has lived with them overtime. 13WWW.GEBG.ORG

Diagram of Conceptions of Global Citizenship Education from the Global South From Global Citizenship Education: Taking it local, UNESCO, 2018RESPECT FOR DIVERSITYPeaceful social relationshipsIntegrity of the motherlandFood securityHarmony with the natural environmentEquitable socio-economic developmentGenerosityHospitalitySOLIDARITYSHARED SENSE OF HUMANITYRelational Learning is Essential This study found that immersive, international, short-term programs designed by schools can help students develop skills and dispositional aspects of global competence, especially when the program prioritizes relational learning, learning facilitated by the opportunity to connect and communicate with community members from the host community/culture. The findings of this study show that short-term immersive learning experiences that provide students an opportunity for intercultural relational learning with partners whom the students perceive as peers (regardless of factors such as age, education level, family income, etc) can support students in developing the essential skills of intercultural communication, perspective taking, and behavioraladaptability.For this study, intercultural communication was defined as the ability to communicate with people who have a dierent cultural background than you (OECD, 2019), and 71.59% of participants (n = 176) reported that their global learning experience in high school helped them to better communicate with people who are dierent from them. The qualitative data analysis showed that one of the key areas of intercultural communication developed by participants through their high school experience was both the skill and the disposition for empathic listening. The prioritization of listening, especially significant for adolescents, also continued to impact participants beyond high school. Participant 32 shared how she continues to see the influence of her high school global learning experience in the way she prioritizes listening: “Even though there may be some communication barriers, such as language, I will go out of my way to really listen to try to understand theperson.” Of the 176 participants reporting, 87% reported that their global learning experience in high school taught them how to be more flexible and adapt to dierent situations. Many of the participants described the significance of being a guest or developing an understanding of the cultural importance of hospitality in the host community, a concept outlined by UNESCO as central to understandings of global citizenship in the Global South (UNESCO, 2018). Participant 18 describes how she learned how “to defer and follow others’ lead… by respecting the culture… by being a guest in other people’s spaces,” demonstrating how embracing being a guest and wanting to be respectful in a new cultural setting contributed to practicing behavioral adaptability.14 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

Summary of Implications and Recommendations For Program Design Related to Global Competence Development GENERAL FINDING SUB-FINDING(S)IMPLICATIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROGRAM DESIGN RELATED TO GLOBAL COMPETENCE DEVELOPMENTParticipants report that RELATIONAL LEARNING WAS KEY FACTOR in their experience Intrinsic motivator for learning both during and since high school experienceProvided meaningful context for critical self reflectionEducators should prioritize relational learning as an intentional driver of program design, if the goal is global competence developmentParticipants report DEVELOPMENT OF THE INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION and continued influence of their high school experienceEmpathic listening as key aspectLanguage learning as contributing to developmentEducators that seek to develop intercultural communication skills in students should consider ways to emphasize listening with empathy as part of communicationParticipants report DEVELOPMENT OF PERSPECTIVE TAKING and some continued influence of their high school experienceInstigator for continued curiosity and open-mindedness, including perspective seeking and listeningSome report a shift from an exclusively North American- centric worldviewEducators that seek to develop perspective taking skills in students should consider ways to foster curiosity through first-person perspective sharing, including with peers, both prior to as well as during learning experienceParticipants report DEVELOPMENT OF BEHAVIORAL ADAPTABILITY and continued influence of their high school experience, especially in new or intercultural contexts Learning how to be comfortable being uncomfortableSignificance of learning how to be a guest in cultures that prioritize hospitalityEducators that seek to develop behavioral adaptability skills in students should consider ways to discuss with students then learning outcomes of being uncomfortable and intentionally include in their program curriculum the complex concept of being a guest in cultures that prioritize hospitalityStudents from Cape Henry Collegiate in Virginia learn about Buddhism at Wat Thai Temple in Washington, D.C.15WWW.GEBG.ORG

High School Experience Shapes Lasting BehaviorsThis study consistently found that participants shared the importance of this experience having taken place during their adolescence. Participant 41 explained that “time of my life that it happened… shift[ed] my perspective, not only on the world but also on myself… It was the literal genesis to start building my identity, in my mind… So it’s shaped literally everything.” For many participants the fact that the learning experience took place during adolescence was a key factor because they described their self-concept and identity as still in formation during that time in their lives, an idea supported by the literature related to adolescent neuroplasticity (Fuhrmann et al.,2015).A major finding of the study was that participants who practiced global competencies (such as intercultural communication and perspective taking) during high school possessed the disposition to put these skills into use in new and varied contexts well beyond high school. Participant 38 describes how listening to stories from community members during his global learning experience made himrealize: “My life is so dierent from what other people have experienced. My privileged life is such a blip on the radar compared to what’s happening in the world. And that sets you up going forward to listen… Before you tell a story or engage in a conversation where you’re the focal point, just maybe consider where other people are coming from… the understanding that what you say has an impact, and your experience is dierent from other people’s experiences is really valuable. And what that does is it flips the switch in yourbrain.” This quotation exemplifies the response of 77% of participants (n= 176) who reported that their high school global learning experience helped them to better recognize that people from dierent cultural backgrounds/identities may see things dierently from them. An ongoing desire to seek out perspectives from various and multiple perspectives is one of the lasting impacts self-reported by many participants. Participant 19 shared her ongoing desire to “learn more about other people, learn more about history and just trying to challenge myself to see from every worldview, even if it’s a view that I don’t align with, I still want to know your view, I want to understand it, I want to know why you think that way, and I want to be uncomfortable, I want to be comfortable with my uncomfortableness.” These findings reflect how educators understand global competence as well as how they might consequently design programs or curriculum to support intercultural communication and perspective taking development in high school students. One of the most significant findings of this study, supported by both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, is that a structured and supported global learning experience during adolescence that is organized by the participant’s high school leads to a strong disposition for continued intercultural learning. This was especially true for participants Participants in GEBG’s Chinatown Collaborative Scouting program in New York City16 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

of color. While students of color continue to be under-represented in higher education study abroad, the quantitative data indicates that participants of color in this study participated in higher education study abroad at higher rates than White participants and report a stronger influence of their high school global learning experience on that decision than White participants. This study found that participants described their learning experiences as a first step in a chain of decisions or thinking that led them to intentionally engage more across dierences and feel more prepared with the skills to be successful in doing so. Limitations of the Experience for Service ProgramsTwo important findings relate directly to the limitations of the experiences for some students or certain types of programs. Students who participated in service-based programs described a significant shift over time in their understanding of the value of these programs. The intensity of many interview participants’ feelings about the service aspects of their programs, for those that participated in programs with this focus, was surprising given the years that have passed between their participation and the interviews. Many expressed emotions of guilt and confusion, often instigated by new courses, readings, relationships, or intercultural engagement. As they described, this guilt and confusion resulted from realizations that these programs unintentionally perpetuate neo-colonial mindsets and problematic power structures (Gandhi, 2018). Participant 12 shared that her current work for an international NGO shifted her perspective on her high school program: “Now looking back after… having more experience…, they marketed it as a volunteer trip… but it wasn’t very meaningful for the people living there… [W]e didn’t have any impact on them… so I feel kind of icky about that, looking back on it, but it’s hard to reconcile it because it did have a big impact on my life and what I want to do, but for the people there,… it’s really just like they’re kind of tourist sites.” She described her ability now, after working, to look at service-focused programs from the perspective of the community visited, rather than just viewing it through her own lens, a direct result of also experiencing meaningful learning and growth through the relational learning aspects of theseprograms. Other participants, however, were much more directly critical of their service-focused programs: some had, over time, come to see them as problematic or as perpetuating what Participant 38 described as a “White Savior Complex.” Participant 17 describes how she came to this view during university: “I learned about these trips and how they’re pretty terrible for the community. Like me, these privileged White Westerners go into their communities, take away their construction work, expect everyone to be nice to us, and smile and go home feeling like we’re heroes and that we’re better people. It’s a really, really messed up type of trip in my opinion… In high school I wasn’t aware, I didn’t have this education, I didn’t know… but now… it’s so blatant and wrong to me that… I view that trip as a mistake.” This reflection captures very directly what several other participants described through their questioning of the service aspects of their experiences, sharing how they have shifted over time to now see the service as reinforcing problematic power dynamics, involving misguided explanations of who is helping whom, and perpetuating neo-colonial mindsets. Ironically, this critical thinking reflects the student’s development of global competencies, explaining why students with this perspective might continue to feel gratitude for the experiences, despite their problematic nature in hindsight. One implication of this finding is that service programs and/or the service aspects of these programs are neither an eective way to develop relational global competence over time (perhaps as a result of the inherent perceived inequity of the student-community relationship) nor to combat global systems of injustice, as much as that might be the intent. 17WWW.GEBG.ORG

The possibility of thoughtful and sustained community learning partnerships that are co-created and mutually-beneficial does exist. This type of partnership centers local agency and informal educating, positioning the student as a learner, and compensating the community partner as educators. However, in order to shift existing service relationships toward this other type of partnership requires significant critical self-reflection amongst stakeholders and dicult conversations between partners, particularly given the challenge that the perspectives of students/families/educators are deeply ingrained and influenced by the societies in which they live. Authentic community learning partnerships are also dicult to execute at the high school level given limited resources (including time) available to build and sustain partnerships as well as the challenge to provide ample time for student critical self-reflection prior, during, and after travel.Limitations of the Experience for Transnational StudentsThe final finding emerging from participants’ narratives is that most participants with transnational and/or immigrant identities reported limited global competence development from their high school global learning experience. Participants shared how their transnational or immigrant identity provided them with previous opportunity to engage in intercultural contexts and to develop global competencies, leading the short-term programs in their high school to have limited impact on them. Participant 13 reflected that she had already developed some of the skills addressed in the interview prior to her global learning experience. When asked about where she believes she developed some of these skills, she shared “I think it probably came from when I was younger, when I moved from Hong Kong to the US for high school - that was a very big change for me”. Similarly, when asked about adaptability, Participant 14 shared that “when I’m at home I only speak Spanish and I very much have a Mexican personality side of me that I can only be when I’m home, [when I’m at school] I have to adapt to be the American side of me,” demonstrating how attending a predominantly White school which greatly diered from her Mexican-American home culture provided her with ample opportunity to practice advanced levels of adaptability both culturally and linguistically. These participants demonstrate how they had already developed significant global competence prior to their global learning experience, even if it was unrecognized by their school and not accounted for in the design of theprogram. While assessing and dierentiating for student prior knowledge and skill development may be common model practice in core academic classroom instruction, this study found that it is not a common model practice for school designed global learning programs. Many programs are implicitly or explicitly designed with an assumed student profile in mind, and that profile does not include a student whose transnational or immigrant identity has led them to prior global competence or linguistic skill development. PISA global competence assessment results indicate that in some countries immigrant students reported higher levels of certain global competencies, even with other educational disadvantages or inequities in place within that country (Schliecher, 2020). When secondary schools discuss ways to make global education and global learning experiences more inclusive, they often neglect to include the need to dierentiate for prior skill development in students with transnational identities. Global educators can build on the developing frameworks to make global learning opportunities more inclusive and more equitable, a clear implication of the qualitative research findings of this study.18 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

Summary of Implications and Recommendations For Improvements in the Field related to a Dialectic Approach GENERAL FINDING SUB-FINDING(S)IMPLICATIONS/RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVEMENTS IN THE FIELD RELATED TO A DIALECTIC APPROACH AND AN EQUITY LENSParticipants with a TRANSNATIONAL AND/OR IMMIGRANT IDENTITY REPORT LIMITED IMPACT and competence development due to prior intercultural experience and skillsPrograms do not meet the learning needs of transnational/immigrant students with high existing skill levels Educators should work to know their students prior knowledge, skills, and dispositions and dierentiate learning experience to provide growth opportunity for all studentsParticipants report that their VIEWS HAVE SHIFTED OVER TIME IN REGARDS TO THE SERVICE ASPECTS of their high school programs and that they NOW SEE THESE ASPECTS AS PROBLEMATICParticipants who have engaged in critical self-reflection report feeling that these programs perpetuate neo-colonial mindsets and systemsEducators should critically evaluate or even reconsider programs with a service focus and look to prioritize relational learning with community partnersParticipants report a significant DISPOSITION FOR GLOBAL AND INTERCULTURAL ENGAGEMENT OVER TIME instigated by their high school experienceSignificant influence of high school experience on higher education study abroad decision making as well as intercultural engagement locally, especially for students of colorEducators should consider how to help students build on their previous learning in college decision-making and ensure they have access to the full range of college/university resources to support this disposition for global learningGEBG regional meeting in New York City hosted by Dalton School, November 202119

A New Approach to Program Design: Embracing Contradictions and ConnectionsOne way for educators to make improvements to program design is to embrace a dialectic approach to global learning pedagogy and program design. A dialectic approach is one that embraces the contradictory nature (rather than trying to minimize it) of wanting our students to engage with the world while being very aware of the multiple intersecting identities and global systems at play in this engagement. Educators can use a dialectic approach to create a more culturally responsive learning experience for transnational students, in which educators dierentiate to provide growth and development for all students just as they would in an academic classroom setting. This dierentiation would allow for the complex and fluid interplay of cultures and identities to engage both within and between participants in intercultural encounters (Martin and Nakayama, 2015). A dialectic approach to intercultural learning prioritizes intercultural connections and relationship building but also “foregrounds the inevitable inequities in power relations that are characteristic of intercultural interactions,” meaning that these inequities are identified, discussed, and examined in context with students (p.22, Martin & Nakayama,2015). To engage with this approach, educators can intentionally help students to recognize and unpack what is implicit and at work as part of their intercultural interaction—in terms of histories and power-dynamics related to the geo-political context of the learning and students entering into that space. Building this approach into the curriculum and pedagogy of a program will lead to more supportive identity formation for all participants as well as critical and contextualized global competence development, especially for those whose identities are marginalized in the location of their learning experience, requiring students to encounter their gender, racial, and/or sexual orientation being openly contested. The dialectic approach to intercultural learning “emphasizes its ongoing and processual nature,” while embracing “the relational and contradictory nature of intercultural interactions’’ (p. 18, Martin and Nakayama, 2015). I hope that this study, and its focus on how these learning experiences live with participants over time, can support educators in creating more thoughtful opportunities designed with a dialectic approach and focused on relational learning. Centering the complexity and the specifics of both the learning context and the learners themselves will allow educators to design learning experiences for students that are competency-based and provide equitable opportunity for growth and development across diverse studentidentities. CLARE SISISKY is the Executive Director of the Global Education Benchmark Group and will complete her doctorate from the graduate school of education at University of Pennsylvania in the summer of 2022. Middle-school students at Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland identify the qualities of successful communities as part of their Virtual Journeys.20 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

BACKGROUND ON THIS VIRTUAL EXCHANGE STUDYThe study was conducted thanks to a research grant AFS Intercultural Programs received to participate in The Stevens Initiative’s “Strengthening the Field: Catalyzing Research in Virtual Exchange.” The study was open from April to October 2021, and it included over 150 high school students from 35 countries, aged 14-17 years old, who participated in the AFS Global You Adventurer. This is a virtual exchange program that includes an online platform containing asynchronous activities and live facilitated dialogue sessions with qualified intercultural educators. The primary goal of this research is to identify and further develop the ecacy of virtual exchange, with the aim of strengthening programs that develop high school students’ global competence. The AFS Global You Adventurer exchange runs on an online platform that includes video modules, discussion prompts in peer forums, interactive activities, and live dialogue sessions, implemented by qualified facilitators. This data was gathered and analyzed using a mixed methods approach to determine if the AFS Global You Adventurer develops stronger perspective-taking skills, reduces stereotypes, improves intercultural Virtual exchanges have a meaningful immediate impact on the development of global competence among high-school aged youth around the world, according to a study by AFS Intercultural Programs, a global non-profit specialized in intercultural learning programs. The “AFS Global You Virtual Exchange Impact Study” implies that it is crucial for students to have meaningful intercultural exchanges, which can be virtual, to develop global competence. written by Corinna Howland, Ph.D., Bettina Hansel, Ph.D., and Linda StuartVirtual Exchange Effectively Fosters Global Competence for High School Students21WWW.GEBG.ORG

communication, leads to greater knowledge seeking, and builds empathy. A comparison group of peers with an interest in other cultures, but who did not participate in the GYA VE program, was used in this study. THE IMPACT OF VIRTUAL EXCHANGE The results of the study demonstrate that short virtual programs, such as the five-week AFS Global You Adventurer (GYA), provide immediate growth in aspects of youth global competence, especially in terms of having a more positive view of peers from other cultures, being able to actively withhold judgment of others by staying curious and open-minded, and increasing cross-cultural communication skills. Specifically, young people who participated in the virtual exchange program showed nearly three times greater odds of growth in “positive regard” (the degree to which one withholds judgements about situations or people that are new or unfamiliar, Kozai Group, 2011) compared to the control group. They also had two times greater odds of overall Intercultural Eectiveness Scale (IES) growth compared to the comparison group (defined as the extent to which one is likely to initiate and maintain positive relationships with people from other cultures, Kozai Group,2011). After completing the program, students reassessed their previous attitudes and communication behaviors and found many areas had been lacking before the AFS Global You Adventurer. The students were able to more objectively assess their intercultural skills which is an indication that they acquire cultural humility through participation in the virtual exchange. WHAT’S NEEDED FOR A SUCCESSFUL VIRTUAL EXCHANGE?According to the study, some of the key elements for a successful virtual exchange demonstrated by the AFS Global You Adventurer program include its highly diverse and multilateral cohorts, and the combination of activities that participants can do on their own time with live facilitated dialogue sessions. Such program structure is set up to grow students’ global competence, and was well-received by participants who reported an enriching and transformative experience. GYA program participants grew particularly on measures of positive regard, relationship development, and cross-cultural communication. Accordingly, short-term virtual exchange programs may choose to focus on a particular dimension of global competence that they wish to develop among their cohort groups. Students in the 14-17 year old age group may especially benefit from repeated reinforcement of key ideas and time to embed these through practice and learning.Many students reported forming friendships, noting that they found their interactions with others particularly enriching. This shows that even within a short timeframe, virtual exchange participants can enhance their relationship development. However, some participants also desired more opportunities to interact. AFS GYA and other virtual exchange programs which have a similar asynchronous course-based structure should ensure as many opportunities for contact as possible are incorporated into course activities, including informal time to chat and form connections. This may be particularly important among the 14-17 year old age group, for whom peer connection is especially significant. NEXT STEPS FOR VIRTUAL EXCHANGE RESEARCHFuture research on virtual exchange should compare the multilateral (students from multiple countries and communities), multilingual programs and against the results of bilateral programs (those with students from just two countries/communities participating). It should also consider longevity through a longitudinal study. With larger numbers of participants, it should also be possible to better assess whether having more synchronous sessions provides added learning value for the participants. AUTHORS AND RESEARCH TEAM // CORINNA HOWLAND, PH.D., Victoria University of Wellington, BETTINA HANSEL, PH.D., AFS Research Consultant, LINDA STUART, Director of Global Education Innovation (AFS Intercultural Programs), with assistance from ANAÏS CHAUVET, Educational Programs Specialist (AFS Intercultural Programs)22 INTERCONNECTED // VOLUME 04

Assessing Faculty Denitions of Global Education LanguageON THE SAME PAGEOVER THE PAST TWO YEARS of the pandemic, schools across the world have pressed pause on travel programs and many have used the time to reevaluate their global programming. While at many schools this unfortunately may have been because this is the first time circumstances have allowed for it, ultimately this type of work is crucial. It gives schools a chance to figure out where global programs live, allows globally minded educators to help push global competencies into the academic program and move away from the model of global education that is exclusively focused on internationaltravel.When our travel programs are on pause, and we aren’t talking about all the great places we go, and the director of global education finally has time to embrace the important strategic aspect of their work that goes beyond trip planning and health and safety protocols, most schools very quickly arrive at a confusing reality. Everybody knows that global ed is beneficial, but very few people can define it, explain its place in the school curriculum, or know how we are supposed to assess its impact on faculty and students. Even when faculty can provide definitions, there is a level of diversity that makes it clear that everyone is not quite on the samepage.This fall, about 20 faculty members were selected for GEBG’s Research Fellowship on developing global competence. For the past eight months this group has been working to assess the impact of global programming and search for ways to help foster stronger global initiatives at their schools. Half of this group was focused on developing faculty global competence. While some schools had already started defining terms and structuring assessment, many noticed that the research was dicult without everyone being on the same page. The biggest obstacle for many became, “how do you assess faculty global competence when there are so many dierent definitions of what itis?”Justine O’Connell, Research Fellow from Mercersburg Academy, found that even though her predecessor did much of the heavy lifting on building a common understanding of the role of global programming, that there still was work to do. “There was still the feeling that global programs are ‘just travel programs’ when in reality we know it is so much more than that,” she shared, but added that the pause in travel has oered an opportunity for collaboration: “Especially in COVID times, there has been more connecting between global program directors across the country and the world. The sharing of ideas, best practices and programming has allowed those in the field to shift from what is usually a department of one or two people in a school, to have a global community.”At Holy Innocents’ Episcopal School, Research Fellow Christopher Yarsawich has found that arriving at common language and understanding can extend even beyond the academic program. At HIES, they used their pandemic downtime to help provide structure and define terms, which helped Christopher find that “It is necessary to share common language for there to be a distinct identity of what global education means and a sense of coherence between programs as students move written by Dr. Aric Visser 23WWW.GEBG.ORG