Return to flip book view

SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3WWW.BOOKSANDRECOVERY.COM

1 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 In This IssueCover Feature – Ed Begley, Jr. .................................2One Q Interview – Mary Beth O’Connor .............. 8 Guest Voice – Christina Dent .................................10Harm Reduction – Dee-Dee Stout ....................... 12Excerpt – Joe Clifford ..............................................14Naked and Afraid – Mandy Horvath .................... 16Coming in Issue 4 Brad Orsted – Photographer, filmmaker, author of Through the Wilderness: My Journey of Redemption and Healing in the American Wild.Dorian Anderson – Author of Birding Under the Influence: Cycling Across America in Search of Birds and Recovery. Alison Owings – Mayor of the Tenderloin: Del Seymour’s Journey from Living on the Streets to Fighting Homelessness in San FranciscoAnd more . . . Happy new year (in March)! After a hiatus in 2024, we are kicking off the new year with more stories of inspiration and hope. I had written a completely different letter for this issue when, sadly, I belatedly discovered that my friend, Rob Hannley, founder and publisher of Recovery Today Magazine, passed away in May 2024. I am writing this letter instead in honor of Rob’s memory and his tireless dedication to spreading the message of hope for people seeking freedom from substance use.Rob never met a stranger. He was endlessly curious and interested in other people’s lives. He was someone you could go a long time without talking to and then pick up right where you left off. As I have mentioned in my previous letters, reading everything I could get my hands on about substance use and recovery helped me get through my son’s years of active use, when he was self-medicating severe anxiety, depression, and trauma. When he took those first steps toward recovery, I was able to begin writing on the topic (although not our personal journey, which is my son’s story to tell, should he ever wish to). I had been a journalist for decades, but Rob gave me my first opportunity to write about our shared passion – helping people find hope after problematic substance use. I interviewed model and businesswoman, Kathy Ireland, about the kathy ireland® Recovery Centers, and later former tennis pro and the cofounder of WEConnect, Murphy Jensen, who is in long-term recovery. Rob featured both as cover stories and had no issue with my reprinting them once I decided to start my own digital magazine. While we had different outlooks and approaches, we shared the same desire – that people would find freedom from substance use and be able to live fulfilling lives, just as Rob did in long-term sobriety.It is my wish that the readers of Recovery Today Magazine, who found hope in Rob’s life and example and work, will somehow find their way to Books & Recovery as we carry on that message. Books & Recovery is dedicated to my son, Calvin, whom I love more than anything, and to William Russell Mitchell (1957 – 1981), whom I will always love.SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 PUBLISHER Rebecca PontonTECHNICAL ADVISOR Emmanuel SullivanGRAPHIC DESIGNER Kim FischerSUBSCRIBE subscribe@booksandrecovery.comCONTACT US For editorial, advertising, and general inquiries, please email rebecca@booksandrecovery.com.The contents of this digital publication may not be reproduced either in whole or in part without the express written consent of the publisher. Every effort has been made to provide accurate data; however, the publisher cannot be held liable for material content or errors. You should not rely on the information as a substitute for, nor does it replace, professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. If you have any concerns or questions about your health, you should always consult a physician or other health care professional. Do not disregard, avoid or delay obtaining medical or health related advice from your healthcare professional because of something you may have read in this publication. Books & Rec and its publisher do not recommend or endorse any advertisers in this digital publication and accept no responsibility for services advertised herein. Should you wish to support the work of Books & Recovery, subscription is free. A gift contribution can be sent via PayPal. Please note: your contribution is not tax deductible. Books & Recovery is not a 501(c)(3) organization. Thank you for helping spread the message of hope.This issue of Books & Recovery is dedicated to Rob Hannley.August 23, 1965 – May 16, 2024Visit www.booksandrecovery.com and subscribe today!

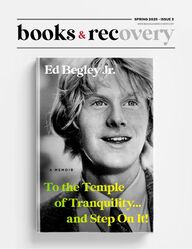

2 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 In Conversation with Ed Begley, Jr.Author of To the Temple of Tranquility … and Step On It!BY REBECCA PONTONCOVER FEATUREPhoto courtesy of Russell Baer.Shot in black and white photography, the camera catches the young man with a look of wonder on his face. His eyes bright and shiny, his mouth forming a half-smile. What was he thinking? About the promising future ahead of him? His goals and dreams? Maybe all of those things. Maybe none of them. One thing is certain, though. He was struggling with substance use so horrific that he was having delirium tremens (DTs) by the age of 27.The young man in the photo is actor and environmental activist Ed Begley, Jr., widely acclaimed for his six time, Emmy-nomi-nated role in the ‘80s as Dr. Victor Ehrlich in St. Elsewhere and,

3 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 “The fire of alcoholism was blazing and I was getting burned, but I knew where to go for help.”more recently, from 2017 to 2024, as physics professor Dr. Grant Linkletter in Young Sheldon, and many more in between. He has received accolades, not only for his acting abilities, but for his enduring commitment to environmental issues long before they were a cause célèbre.Born and raised in Los Angeles, Begley is the son of Academy Award winning actor, Ed Begley, Sr., who won Best Supporting Actor for his role in Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), and Amanda Begley – or so he thought.“Nothing in our family was what it seemed,” he was quoted as saying to the Wall St. Journal while on tour to promote his memoir, To the Temple of Tranquility … and Step On It! (Ha-chette; 2023). Upon seeing a blank space where his mother’s name should have been on his birth certificate, Begley was stunned to learn that the woman he had thought was his mother his entire life – 15 and a half years, at that point – was not his biological mother.Begley refers to the revelation as the “inciting incident” that preceded his problematic alcohol and substance use, a realiza-tion he came to during the writing of his memoir. “I’m not sure I knew it before. I found out this shocking news and I realized that there was a big lie that had been told my whole young life.”The deception was so traumatic and had such a profound impact on him that Begley, who was “bad at lying,” wished there was something that could help him become a better liar. “I quickly found that there was something awaiting me.” He discovered some Seconal (“sleeping pills”) that his father, who was in recovery from alcohol use disorder, had been prescribed, but didn’t feel comfortable taking. “This was in the mid-60s,” Begley points out, “and we didn’t know a lot about pills back then. People generally thought, ‘If the doctor prescribes it, it’s just fine. You take what the doctor tells you to take.’ Sometimes, it’s really not what you need; in fact, au contraire, it’s exactly what you do not need. My dad probably didn’t need them and he knew it; I didn’t need them and I didn’t know it.” Begley’s father passed away in 1970, when Begley was just 21, giving him the freedom to pursue a closer relationship with San-dy, the “family friend” who, in reality, was his biological mother. “Without being disrespectful to my dear mother,” Begley says, “there was too much water under the bridge” to develop a typi-cal mother-son relationship. He had also discovered over the years that his mother was a hoarder.1 He believes “she was hanging on to things that she felt she needed because of the things she had lost in her life” – namely, her children. To this day, Begley is unclear of the cir-cumstances that resulted in his mother relinquishing custody of him and his sister to their father and his wife. “Maybe there’s some point in the hereafter that I get to know how that all hap-pened,” he muses.Acknowledging how traumatic it must have been for his mother to lose her children, he says he tried to be sensitive to that in his interactions with her. “It was unfortunate and I felt for her.”Begley and his mother were dealing with their shared trauma in their own ways. What had started with pills was the beginning of substance use that escalated to include what Begley refers to Ed and Rachelle Begley. Photo courtesy of Russell Baer.1 In 2013, hoarding became classified as a diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorder – 5th Edition (DSM-5), American Psychiatric Association.

4 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 as “solid, liquid, and gas – I used anything I could to get high,” covering all the bases with pills, alcohol and even, for a period of time when he was younger, nitrous oxide from cans of Reddi-wip.The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) estimates that 50 to 60 percent of the vulnerability to alcohol use disorder (AUD) is inherited. Begley’s father suffered from AUD for about 30 years before getting sober and Begley readily admits he drank, in part, to emulate his father and other hard-drinking, successful actors of the day, like Richard Burton, Oliver Reed, and Peter O’Toole, telling YES! Weekly, “I thought it was the drinking that made them great; I wanted to drink like a man.”He and his father shared a non-linear path to sobriety, with Begley relating a story about a trip his father and his father’s brother, Martin, made to Ireland with the elder Begley deciding, “It’s Ireland,” and according to Begley that “shot of Old Bushmills – or whatever – started a jag that lasted several years because he thought he could drink again.”Begley admits it is something he also did repeatedly, convincing himself he would have “just a little wine with dinner,” but says it always led to the same place, “which was a quart of vodka, in my case, a gram of coke and whatever pills I thought I needed to sleep or to function – even heroin on four occasions – so it was a deadly combo.” Confessing that he drove around Los Angeles, and other parts of California, under the influence, Begley says the fact that, “I didn’t kill anybody, Rebecca, is one of the great gifts, one of the miracles, of my existence.” (He makes it a point during our conversation to express his gratitude to his friends at Van Nuys High School for taking away his keys, and says, “I can thank my friend Rick Fish for that. He saved me from hurting myself or, even worse, hurting someone else.”)There is another episode from his past that will forever be seared into his memory. Working on the 1977 Jonathan Demme movie Citizens Band with Paula Matt and Candy Clark, in what he calls “ a medium sized role” as the priest, he had gone on “a real bender” the night before a 6 AM call time. “I took one breath about halfway through this bottle of chardon-nay after a fourth of vodka and a bunch of cocaine.” Suddenly, Begley recalls, “The room got a funny look to it and I realized I was no longer drunk. I was certainly not sober. I was in the neth-erworld where the booze had stopped working and everything looked a little sinister. It was like storm clouds brewing even though we were inside.”Making his way back to his hotel room, all he wanted was to sleep it off. Fully awake, but closing his eyes in an attempt to get some desperately needed sleep, a vampire suddenly ap-peared and prepared to bite his neck, followed by a guy hanging from a noose right in front of him, and then zombies filing into his room. The waking nightmares and hallucinations continued all night. At 27 years old, Begley was in the throes of delirium tremens (DTs), a potentially fatal form of alcohol withdrawal.He somehow managed to make it to the set on time – “For-tunately, I did not get fired, although I’m not sure what the hell level of work I was able to do” – and made his way back to his hotel, where he experienced what he says is called “the God shot – a gift from above.” His soon-to-be first wife, Ingrid, asked if he needed a pill or “one little medicinal shot” of [alcohol] to relieve the shaking.“I was so bad off, this was the first time, Rebecca, I couldn’t even think about taking a Valium or some pill to stop the pain. I knew it wouldn’t work just as the alcohol wasn’t working.” He wanted nothing more than to take a hot bath and watch TV, as long as it “wasn’t a monster show, having seen a real monster marathon on the back of my eyelids the whole night before.”Turning on the TV, Begley was met with a blank screen. There, literally, was nothing on the TV even though the channel had worked previously. He was about to get up and change the chan-nel manually “as we did back in those days,” when the credits began to appear on the blank screen … David Wolper presents Dick Van Dyke in The Morning After … “It was a show about alcoholism. I watched the whole thing. I didn’t move. I couldn’t believe it started the very second I turned on the TV.” As soon as it was over, Begley made a call to a 12-step program. “How did I have the number?” he asks rhetorically. Years before, he had clipped a tiny section – “about the size of a fortune cookie” – from The Hollywood Reporter Ed Begley, Jr. in the Klamath-Siskiyou Forest in CA in 2002. Photo courtesy of EBJ.

5 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 with the number and taped it to the back of his wallet, likening it to the familiar glass box in the hallway at school that reads, “Fire extinguisher: In case of fire, break glass.”“The fire of alcoholism was blazing and I was getting burned, but I knew where to go for help.”His second call was to a friend in LA even though he was 400 miles away in Marysville, California, working on Citizens Band. Assuring Begley that they would attend a meeting when he got back to LA the following week, the friend told him not to drink or use – and he didn’t.“It was that incredible coincidence or call it what you will, but I finally wanted recovery,” Begley says. Despite the fact that it took five or six tries – “in and out, kind of like a revolving door” – he says he eventually got it right, in no small part due to his late friend Billy Boyle’s insistence that Begley. Was. Not. Going. To. Drink., including the time Begley was just as insistent that he was.At LAX, waiting for a flight to Cuer-navaca, Mexico, to film the movie The In-Laws with Peter Falk and Alan Arkin, he ordered a Bloody Mary as soon as the bar opened at 8 AM “nice and early for the people that need a drink at that hour,” and then he remembered “Billy g–damn Boyle.” He went over to the pay phone – “there were no cell phones in 1978” – and called Boyle. After a war of words, in which Begley was adamant that he was going to drink and Boyle was just as adamant that he was not – and listed all the reasons Begley didn’t even want to – he pulled out his ace card. “You called me.” After Boyle told Begley to call him when he got to Mexico, Begley heard the sound of a dial tone (which he reenacts in the retelling of the story). “He hung up on me!” Begley says, still sounding somewhat incredulous. He walked over to the bartender, asked what he owed for the Bloody Mary, and told him to pour it down the drain.“That’s the way it works. It was extremely powerful, extremely powerful, and it still is to this day.”Begley remained sober for the next year and a half, but then attempted to drink again because, as he says facetiously, “I’m a very special person, Rebecca. Back then, certainly, very special. Busy schedule doing movies, busy, busy man, different from everybody else. I didn’t have the time to get a sponsor, I didn’t have time to work the steps the way other people did.”“Big shocker – I drank again,” for what he calls “three candy ass days.” The first night, he drank a few glasses of wine – “sick as a dog.” The second night, assuming he must be allergic to red wine, he drank a chardonnay – “sick as a dog.”On night three, he switched to beer – “sick as a dog.”“I finally realized I could not drink any amount of liquor. That was December 21, 1979, and that’s the last time I had a drink, pot, pill or anything of an alcoholic or addictive nature. I chose to finally do it and commit to it, getting a sponsor, working the steps, and what a shock – here we are 40-some odd years later.”Begley married his second wife, Rach-elle, in 2000 and they share a daugh-ter, Hayden, as well as Amanda and Nicholas, his two children with Ingrid. It was Hayden who encouraged Begley to share stories from his life “before I forget them.” He says living and working in Hollywood, and society in general, where drinking is socially acceptable, “has been a test, like what Isaac and Abraham went through – ‘Sacrifice your son’ and then, at the last minute, ‘Just kidding, you don’t really need to do that.’”Begley was convinced that, once he gave up alcohol and other drugs, he would forfeit his comedic abilities, but was resigned to the fact that was the sacrifice he would have to make to maintain his sobriety. He still believed the renowned British actors of the day had reached those heights “because they were well-oiled,” discounting all the time and training and countless parts that had led to their becoming the great actors of their time. He admits that one of the reasons he drank is because he wanted to be like them. “I thought it was about the liquor, so I thought I had to be willing to give up being funny.”He recounts a story that happened about three months after “I finally got sober this time – the final time” and some other actors were sitting in a semicircle in their chairs, waiting on makeup or rehearsing their lines, and Begley was standing. The other actors were laughing at something behind him and, when he In the garden with Bunny. “I found love again.” Photo courtesy of EBJ.“I had to be willing to give it up just as one must commit fully to anything of value.”

6 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3turned to see what it was, there was nothing there. It dawned on him that they were laughing at something he had said.“Holy sh*t,” Begley recalls. “I didn’t know I could ever be funny again. It was a great moment of realization: I had to be willing to give it up just as one must commit fully to anything of value.”In his memoir, Begley reveals that he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2016, al-though he had been experiencing symptoms long before that. He takes the same approach to dealing with the neurological disorder as he does to his recovery, which is doing everything he can to stay on the path to health and wellness. As he said in an April 2024 interview with Brain and Life, shortly after he shared his diagnosis, “Parkinson’s is my reality now. But I’ve always been successful with things over which I have control.” Although 12-step programs adhere to the idea that people are powerless over their substance use, they are not powerless over their lives.Just as Begley turned to pills as a teenager to learn to be a better liar (at least, that was the reason in his young mind), he says, “Rigorous honesty is a good way to live. The best attribute I’ve gotten from the 12-step programs I’ve been involved in is, when you’re wrong, promptly admit it.” From those first steps toward recovery over 45 years ago, the truth has set him free.Ed Begley, Jr. is an award-winning actor, longtime environmental activist, and the author of To The Temple of Tranquility and Step on It!: A Memoir (Hachette Books; October 2023). In addition, he is the author of a number of books on eco-conscious, sustainable living. To learn more, visit Begley Living.Ed Begley, Jr. in Studio City, CA, in 1974. Photo courtesy of EBJ.

7 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3ACROSS 1 Alcohol free 4 Co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, 2 words 8 Vital gas for human survival 9 Co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, abbreviated 10 Something which lowers one’s status in other’s eyes 12 Choose 13 Prohibit 14 Retreat and a haven 16 Path or route 17 Corporate designation suffix, abbr. 18 To and _ 19 Type of drink that can become problematic 23 Make a mistake 25 Watch closely 26 Medication assisted treatment, abbr. 27 Remove harmful substances 31 Spanish article 32 Illicit drug that can potentially cause fatal overdoses 35 Originate 36 Where the statue of Cristo Redentor stands (Brazilian city) 38 AA precepts, The _ Steps 39 Recovery _ it’s based on Buddhist principlesDOWN 1 Buprenorphine that is administered by injection 2 Resists 3 Uncooked 4 Medical professional prefix 5 The Hazelden _ Center 6 AA manual, The _, 2 words 7 Invitation to _ 10 Name for some “self-care” centers 11 Damage 12 Cry of pain 15 Prefix with propyl 20 Purge 21 Pronoun that refers to a male person 22 Allow 24 Thorough physical inspection 28 One-on-one teacher 29 Nalax _: medication used to reverse an overdose 30 Declined 32 Healthy and well exercised 33 Off-road vehicle, abbr. 34 Year, for short 37 Surprised expressionCreated by Myles Mellor. www.mylesmellor.comSee page 18 for answers.BOOKS & RECOVERY PUZZLEYOUMATTERTEXT.CALL.CHAT.WWW.WORTHSAVING.CO Click to solve

8 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 One Q Interview withMary Beth O’Connor1 Secular Organization for Sobriety (SOS) is the parent organization to today’s LifeRing Secular Recovery.Rebecca Ponton: Given the stigma that still exists around drug use, and targets drug users, specifically, why did you choose to use the word “junkie” in the title of your book?Mary Beth O’Connor: “Although I wouldn’t use “junkie” to refer to anyone else, I chose to use it in the title because From Junkie to Judge captures the arc of my story in just a few words. Also, there’s a contrast between the high social value of “judge” compared to the negative judgments ascribed to “junkie.” I also wanted to own that I shot meth, because that drug and method of consumption are stigmatized in society and the media even more than drug addiction generally. I also hoped that knowing that I recovered from many years of intravenous methamphetamine use would be a reas-surance to those still struggling and those who love them.” From Junkie to Judge by Mary Beth O’ConnorEXCERPTAs another technique, I reviewed my core strengths. In childhood, before the worst abuse and addiction, I’d been smart, verbal, and precocious. In high school, even as my substance use disorder escalated, I’d excelled. In college, when I’d had partial control over my drug dependence, I’d achieved impressive grades and worked part-time and dealt with trauma and Martin’s abuse. I’d been accepted to a prestigious law school. I’d managed my money, contrary to the spend-thrift modeling of my mother. I’d learned to cook, not well but well enough, built friendships, negotiated with roommates, and satisfied my shared-housing responsibilities. These memories were excruciating because I had lost so much, yet they were also encouraging. For the next ten years, in the midst of my post-college addiction, I’d developed computer and organizational skills. My declining income and periods of unemployment, rather than excessive spending, caused my financial problems. I’d partnered with Doc, so I had a stable living environment. I had some friends, several of whom didn’t abuse drugs. Lucky in my health, I’d dodged the intravenous drug use diseases such as HIV and hepatitis. As a middle-class white woman, I didn’t have an extensive criminal record, notwithstanding that I’d carried drugs every day and had interacted with the police multiple times due to traffic violations. Also, in meetings, I realized I didn’t have unique pain. Many people had been abused or raped or both, yet now thrived. Others had navigated losses, family challenges, or mental health issues. Even friends without addiction histories could lose their bearings, but then climb out of the abyss. This knowledge con-vinced me that the promised land existed if I worked hard to reach it. As long as I kept the chemicals out, my brain could guide me forward, and I could evolve into a capable woman. Considering all this, I decided to expand my recovery to in-clude the trauma as a prerequisite to living my ideal life. If I didn’t better manage my anguish, I risked turning to speed to ease my pain or, to state it in positive SOS terms,1 dealing with emotions will desensitize you to the drug’s pull. Without meth,

9 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 I felt more deeply. My knee-jerk reaction was to box up my feelings and shove them down, which cut me off from myself and prevented further growth. Plus, ter-ror often washed over me, sometimes for days, when I thought of facing my abuse wounds. I needed to overcome this despondency, which threatened to drag me down into sober misery. So, I located a therapist with abuse and addiction expertise. During this work, I grieved my short-changed childhood and related adult destruction. I even considered how much easier it would be if I turned the wheel of the car and drove off a cliff. Yet, as promised by my counselors, feelings and memories became prominent in pieces, not all at once. I started to learn how to allow my emotions to bubble up so I could exam-ine them and discover what they were telling me, whether about the past, the present, or my fears for the future. All my recovery work taught me a fun-damental concept. Trauma and neglect probably were the primary drivers of my substance use disorder. But the parents and abusers who broke me were not going to fix me. I had to repair myself. As Women for Sobriety (WFS) teaches, I would no longer be victimized by my past. This didn’t mean I had to travel this path alone, though. Self-empowerment also means seeking out the assistance you need: professional help, support groups, recovery buddies, or family. If one avenue fails to yield the desired result, reevaluate and give it another shot. For an effective recovery plan, I needed to counterbalance the negative parts of being meth free. I missed the rush and the high, so I would glamorize the experience. Plus, my life could seem mundane as I slowed down the pace and no longer raced from crisis to crisis. I’d relive the joy as I anticipated the first shot and the power of the meth. Then I’d force these images from my mind and remind myself that if I picked up crank, I’d be lost again. When I reminisced about in-tense telephone discussions, I reality checked myself. On most drug days I couldn’t concentrate long enough to chat or was so manic I dominated the conversation. To talk myself out of labeling my new lifestyle boring, I reviewed the parties I’d skipped because I was in the tweaky phase of a drug run. Now, I visited with friends, remembered birthdays, and attended recovery events. I didn’t create chaos and new problems but instead set goals and moved forward. On occasion, I could believe that from this base I could handle unexpected challenges, if something went amiss, instead of sinking into a pit of despair.Excerpted from Mary Beth O’Connor’s book, From Junkie to Judge: One Woman’s Triumph Over Trauma and Addiction (January 2023). Reprinted with permission from Health Com-munications, Inc.Mary Beth O’Connor has been sober since 1994. She has also been in re-covery from abuse, trauma, and anxiety. Six years into her recov-ery, O’Connor attended Berkeley Law. She worked at a large firm, then litigated class actions for the federal government. In 2014, she was appointed a federal administrative law judge, a position which she held until 2020. O’Connor is a director, secretary, and founding investor for She Recovers Foundation and a director for LifeRing Secular Recovery. She regularly speaks about mul-tiple paths to recovery, to groups such as Women for Sobriety. O’Connor’s op-ed, “I Beat Addiction Without God,” where she described combining ideas from several secular programs to create a robust recovery foundation, appeared in the Wall Street Journal. For more information, please see O’Connor’s website.Kathleen Cochran, Founder

10 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 With more than 16 percent of Mississippi adults struggling with a substance use disorder, many families are trying to understand what happened to their loved one and how to engage in a help-ful way. Addiction is a complex health crisis, but an experiment called Rat Park is helping us understand it better. There is hope, and there are better solutions that save lives and help more people and families thrive. But first, we have to shift our focus from the drugs to the reason people use them.Dr. Bruce Alexander grew up in the 1950s and ‘60s hearing a lot of the same messaging used today about drugs. People who use drugs are bad, and so are people who become addicted to them, he learned. But the ultimate enemy is the drug itself. As an adult, Dr. Alexander became a psychologist and was as-signed to work at an addiction treatment clinic. He was nervous because he had been taught that people struggling with addic-tion were liars and thieves. As he worked at the clinic, he started seeing something unexpected. The people he was treating had problems he could easily understand. They had rea-sons for their drug use that made sense in the context of their life experiences, even if they were coping in a very unhealthy way. What he was seeing went directly against the con-clusion of a 1960s experiment where a rat was put in a special box that allowed researchers to study its behavior. The rat in this experiment was put in What We Can Learn From the Rat Park ExperimentBY CHRISTINA DENT

“If people struggle with addiction, it doesn’t mean they’re bad. It means they’re hurting.”a box with a lever they could push to inject themselves with a little heroin or cocaine. The rat often pressed the lever, sometimes so frequently that it overdosed and died. The experiment was repeated numerous times, and the message that came out was clear: These drugs are so addictive and deadly that if you start using them, you won’t be able to stop until you die. It reinforced the dominant narrative that the power of a drug drives addiction.However, Dr. Alexander noticed that the experiment didn’t match up with what we know about rats. They are highly social creatures, like humans. They love to play, explore, and socialize. Yet the boxes used in the experiments were small and empty, and the rat was alone. So, Dr. Alexander and several colleagues did their own experi-ment. They kept the lever for the rats to get drugs anytime they wanted, but they built a new environment called Rat Park on the floor of their laboratory. It had lots of room, toys to climb on, and plenty of rat friends. It was everything a rat could want. In a shocking twist, even though the rats could push the lever to get drugs any time they wanted to, they rarely did. In Rat Park, they preferred to be sober. Dr. Alexander concluded that rats’ drug use wasn’t driven by the drug. It was driven by their environment. When they were happy and had their needs met, they didn’t want the drugs. When they were stripped of everything that makes a rat happy, they used drugs excessively. His results with the rats in Rat Park fit with what he was learning at the clinic from real people struggling with ad-diction. It was their suf-fering, not the drug, that led them into addiction. Every person is influ-enced and shaped by experiences that happened as recently as this morn-ing, and as long ago as childhood. Be-haviors don’t exist in a vacuum. If people struggle with addiction, it doesn’t mean they’re bad. It means they’re hurting. The hurt could come from abuse, neglect, mental health challenges, disconnec-tion, guilt, loss, isolation – any number of painful experiences. Inflicting blame, shame, and pain has always been a futile way to stop addiction. Now we know why. James Moore, a Mississippi resident who lost his only son to an overdose several years ago, used to think about his son’s drug use as bad behavior that needed correcting. As he learned and changed, he now describes it as, “A way to turn down the volume of the things that are hurting you.” If we want to meaningfully address addiction, we have to focus on the pain driving it, not the drug being used to cope. Arresting people for drug use will never solve the addiction cri-sis because it uses pain to try to solve a problem that is made worse by pain. Healing, not handcuffs, is the path out of the addiction crisis. This article is adapted from a chapter in Curious: A Foster Mom’s Discovery of an Unexpected Solution to Drugs and Addiction (Throne Publishing Group; November 2023) by Christina Dent. Christina Dent is the founder and president of the nonprofit End It For Good which invites people to support approaches to drugs that prioritize life, preserve families, and promote public safety. Dent supported a criminal justice approach to drugs until her experience as a foster parent prompted a radical change of mind about the best ways to reduce drug-related harm. What she learned changed her mind about the best ways to reduce drug-related harm, and in 2019 Dent gave a TEDx Talk – End the War on Drugs for Good – and launched End It For Good to invite others to consider a different approach. Dent’s book, Curious, is the story of her journey, as well as an invitation to learn alongside her and decide for yourself the best path forward. | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 11

12 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 Whoever saves a single life is considered by scripture to have saved the whole world.– Jewish saying from the TalmudNote: Since we often discuss the history of harm reduc-tion through the lens of academia and white culture, I thought it would be more inter-esting here to view it through others’ lenses. What follows is terribly in-complete and brief, but I hope it gives you a taste of some of the other important con-tributions of BIPOC, 2SL-GBTQIA, and other over-looked communities to the origins of HR. In Midland, Michigan, in the early 1970s, I was part of a small group of teens being trained in how to handle “bad trips” by lo-cal psychologist Dr. Don Crowder (who was also my doctor). Dr. Crowder wanted to open a safe space for teens who were experimenting with drugs – mainly hallucinogens (plus alcohol of course) – as well as train a few teens to help their friends. Teens were using such large amounts that they were at risk for reoccurring, lifelong prob-lems in this mainly white, upper middle-class to high socio-economic town. (Please know that my hometown was, and is, the international headquarters for Dow Chemical – Saran Wrap, Ziplock bags, and napalm bombs. Go Dow!) Dr. Crowder understood these well-off kids had the resources, i.e., time and money, to be using drugs far more often and in greater amounts than those not in those wealthy circles. (My dad was one of the few in town who didn’t work for Dow.) When the City Council heard what Dr. Crowder had planned, they quickly shut him down, saying, “We don’t have a drug problem in Midland, Michigan!” Right. No one wanted to listen to his prescient pleading. Sadly, this training to reduce the po-tential harm to teens never got beyond that initial effort, but it left an impression on me even though I had been using drugs since age twelve. It took me nearly twenty years more to realize that this was early harm reduction work. Midland was a town of about 30,000 in those days, and not a great example of harm reduction overall (as you just read). It was also mainly white. I can recall precisely when the first two Black families moved in. They worked for Dow. The son of one family beat me out for Class President at Northeast Junior High; the other became members of our church, Midland United Church of Christ, where I taught their sons Sunday School. Slowly, it made me won-der if other communities, especially where drug use was even more prevalent, were able to hear those early messages of reducing harm for their residents engaged in risky behaviors and using il-licit substances? What was happening in the big cities, which were now predominantly populated by People of Color and others marginalized? Surely they would heed these messages of help. According to the National Harm Reduction Coalition (NHRC), harm reduction has its roots in many different causes and or-ganizations: The Black Panthers, who started a free breakfast program for children, as well as advocating for healthcare for all. These, and other progressive concepts, were designed to not only keep their communities alive, but to help them thrive and be the next generation to propel this “radical work” forward, assisting people who have been oppressed for so long. A Little History (of an Often-Overlooked Part) of the Harm Reduction MovementBY DEE-DEE STOUT, MA

13 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 The Young Lords Organization (YLO) is another group credited for influenc-ing NHRC and spreading harm reduction in the US. Founded in Chicago in 1968, YLO saw its NYC branch create a program of acupuncture for “addicts” living in the Bronx. According to the website of the Museum for the City of New York, the Young Lords were a multi-ethnic, Puerto Rican-centered group originating after the garage workers strike in NYC in 1969. Here is more on the group from its website: It was the summer of 1969, and the group had blocked traffic on 110th Street with piles of garbage to protest inadequate sanitation services. They had already asked the city for brooms to clean their neighborhood’s streets and, when refused, they went ahead and took them. The “garbage offensive” was the first campaign of the city’s Young Lords Organization, a radical “sixties” group led by Puerto Rican youth, African Americans, and Latinx New Yorkers. New York’s Young Lords, although originally part of a national organization, reflected the lived experiences of Puerto Ricans in New York City. The group mounted eye-catching direct action campaigns against inequality and poverty in East Harlem, the South Bronx, and elsewhere. Other groups of repressed peoples are also seen as foundational to the harm reduction movement for drug users. For example, the drive toward better healthcare for women particularly in sexual health, increasing 2SL-GBTQIA+ rights and treatment for queer folx in particular, during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, was also crucial to establishing NHRC values and how we view harm reduction today. These prior activist movements also helped the national harm reduction movement’s growth in other areas, such as learning concepts of organizing, ways to motivate others into action, and how to interact with the public – sometimes radically – to gain political and media notice. These various groups of historically resilient people carried the lessons of their ancestors about harm reduction; it was and is in their blood (though it wasn’t called harm reduction then; it was called survival). Groups with a history of being oppressed always know a lot about survival and, therefore, they have always known harm reduction.Excerpted from Coming to Harm Reduction Kicking & Screaming, 2nd Edition: Stories of Radically Loving People Who Use Drugs by Dee-Dee Stout, MA, and Joe Clifford, MFA (Square Tire Books; March 11, 2025) with permission.Dee-Dee Stout, MA, has several degrees including an undergraduate degree in business management as well as degrees in psychology & human sexuality. She also earned a Special Major Master’s de-gree in Health Counseling, focus-ing on substance use disorders and relapse prevention. Stout is currently Adjunct Associate Professor at St. Mary’s College in Moraga, CA, teaching a course in their Graduate Counseling KSOE department as well as in their new trauma certificate program. Stout has been recovered for de-cades from long-term chaotic drug use. For more info, visit Dee-Dee Stout Consulting.RELEASE DATE March 11, 2025

14 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 This is the part they don’t tell you about in the movies. Or in On the Road. This is not rock ’n’ roll. You are not William Burroughs, and it doesn’t make a damn bit of difference if Kurt Cobain was slumped over in an alleyway in Seattle the day Bleach came out. There is no junkie chic. This is not Soho, and you are not Sid Vicious. You are not a drugstore cowboy, and you are not spotting trains. You are not a part of anything – no underground sect, no counter-culture movement, no music scene, nothing. You have just been released from jail and are walking down Mission Street, alternating between taking a hit off a cigarette and puking, looking for coins on the ground so you can catch a bus as you sh*t yourself. Now you are walking up 6th Street and the brothers are calling out, “Welcome to Crack Central, muthaf*cker!” It is nothing but drab facades and prostitutes bursting out of vinyl halter-tops, mottled skin, and maple-ripple cellulite. You walk among the scurrying vermin as police sirens wail and car windows shatter, through the clusters of pockmarked hooligans and spooky skulls sucking off the menthol butts they’ve scavenged from the gutter, nursing their 40s and lounging in this one big urban ashtray. See a crack whore peddling an iron. It’s not a new iron. It’s not a particularly interesting iron, nor is it loaded with fancy features. It’s just a regular, plain ol’ iron, and you think, “Wow, what a tough sell…” Empty cups and empty bottles, empty hearts and empty homes. Nobody has a mother out here. Nobody has a past. A past is too inconvenient. You learn not to flinch when the black and whites cruise by. Steam rises from the grates, and the bums in their beaten wheelchairs with their filthy kittens on a string plead for change. A bullet to the brain would be kinder.You could wonder if derelicts celebrate birthdays or Christmas, and you could wonder how they got here, but you already know the answer. They were on the bus with you. Notions of shooting stars are very fine, indeed. You do not worry about death. You will not be that lucky. It’s not whether you can get away with snatching that purse or that Snapple from the store. It’s not whether you can get a Jail and the SicknessBY JOE CLIFFORD, MFAPhoto courtesy of Niki Pretti Photography.

15 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 Re-release coming in Spring 2025state agency to float you food stamps and bus tokens. You can. That’s the problem. You will always find a way to steal what you need to keep going. And you can always find someone to feed you, clothe you, pity you. Sometimes they’ll even let you sleep on their floor, where you’ll get to listen from the bathroom as they fight in the kitchen and she’s screaming, “I don’t want that piece of sh*t in here!” And so you close your eyes and pray to God that maybe tonight will be the night you won’t have to wake up in the morning. No, they don’t tell you about that part.Excerpted from Chapter Ten of Junkie Love by Joe Clifford (Bat-tered Suitcase Press; March 2013) with permission from the author. Junkie Love will be re-released in 2025 with a new Foreword by Josh Mohr (Model Citizen: A Memoir).Joe Clifford, MFA, is the author of several acclaimed novels, in-cluding Junkie Love, Say My Name, and the Jay Porter thriller series. He lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with his two sons. He has been in recovery from heroin use since 2002. Clifford’s writing can be found on his website.

16 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 Rebecca Ponton: What was your life like before the train ac-cident?Mandy Horvath: The train accident occurred on July 26, 2014, just over a month after my 21st birthday. Before losing my limbs, I worked as a chef, a career that allowed me to express my cre-ativity and passion for food. I had always been deeply connected to the outdoors, having grown up hunting, fishing, and foraging. Nature was not just a pastime for me – it was a way of life.Academically, I was an ambitious student and graduated from high school at the age of 16 with honors. At the time of my ac-cident, I was still young, full of curiosity, and eager to explore all that life had to offer.RP: Do you feel you had a problematic relationship with alcohol before the accident?MH: Yes, I absolutely had a problematic relationship with alcohol before the accident. As I mentioned earlier, I was young when I began working in kitchens – environments where alcohol is not only prevalent but often deeply ingrained in the culture. Long hours, high stress, and the fast-paced nature of the industry made drinking feel like a normal way to unwind. At that age, I Q&A WITH Mandy HorvathThe first bilateral amputee to be featured on Discovery Channel’s Naked and AfraidMandy Horvath and her partner Jonny Yates. Photos courtesy of Discovery Channel.

17 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 didn’t fully recognize the impact it was having on me or how it was shaping my coping mechanisms.RP: It’s certainly understandable that you would turn to alcohol after the horrific circumstances of the accident (of course, the loss of the lower half of your legs, but also the police assuming it was a suicide attempt, no testing for a date rape drug, the loss of consciousness and memory surrounding the accident, etc. and the resultant PTSD). How did your image of yourself change after the accident? How did you come to terms with the changes and challenges in your life?MH: After the accident, I lost faith in myself. My confidence was shattered, and I felt as though everything that had once defined me was stripped away in an instant. I struggled with self-esteem, questioning my worth and identity in ways I had never faced before.One of the hardest parts was losing my sense of femininity. Society places so much emphasis on physical appearance, and I couldn’t help but feel like I no longer fit the mold of what a woman was “supposed” to be.During this challenging period, my father, in his own way, tried to motivate me. One day, as I was watching TV, newly amputated and not yet healed, he looked at me and said, “You're a fat piece of sh*t that will never amount to anything.” At the time, I took his words very personally, feeling hurt and diminished. However, I later understood that he was scared and intended to motivate me and, in a way, he did.In January 2016, just two years after my amputations, I moved to Colorado, seeking a fresh start and new opportunities. By 2018, I began climbing mountains, embracing challenges that tested my physical and mental limits. These endeavors played a crucial role in rebuilding my self-image. I realized that strength, resilience, and the ability to overcome adversity are integral parts of who I am. Over time, I learned that my femininity wasn’t de-fined by my body; it was defined by my courage, perseverance, and my ability to rise despite everything I had been through.Through these experiences, I came to terms with the changes and challenges in my life, transforming my pain into purpose and redefining my sense of self.RP: Even after you began hand climbing and accomplishing such incredible feats, you still struggled with alcohol use disor-der (AUD. What was the turning point for you? What was your path to sobriety? How do you maintain your recovery today?MH: While I am proud of my journey toward sobriety, I want to emphasize that my recovery has been far from linear. I have faced significant challenges along the way, and I believe it’s important not to sensationalize or place my recovery on a ped-estal. Today, I advocate for sobriety from alcohol and support the use of medicinal marijuana and psilocybin mushrooms as therapeutic tools.I battle with Phantom Limb Syndrome, a condition that causes sensations of pain in limbs that have been amputated. Instead of relying on narcotics, I use medicinal marijuana to manage this pain. Research suggests that medical marijuana can be a viable treatment option for phantom pain sufferers, offering relief where traditional medications may not. For my PTSD, I have found psilocybin mushrooms to be benefi-cial. Studies have indicated that psilocybin, the active compound in these mushrooms, can help individuals with PTSD by promot-ing emotional processing and reducing avoidance behaviors. Mandy Horvath is a creative writer, public speaker, actress, mountaineer, and the first double amputee to be featured on Naked and Afraid.

18 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 It’s important to note that while these alternative therapies have been effective for me, they may not be suitable for everyone. I encourage individuals to consult with healthcare profession-als to determine the best treatment options for their unique circumstances.RP: In addition to the physical challenge of Naked and Afraid, you are on national TV without any clothes! What was your thought process in deciding to participate in the show?MH: Naked and Afraid is often called the “Everest of survival challenges,” and for good reason. It pushes contestants to their absolute limits, stripping away all comforts and forcing them to rely solely on their skills, resilience, and mental fortitude.While I have climbed Kilimanjaro, I will never climb Everest. The mountain has become overcrowded, littered with trash, and tragically lined with the frozen bodies of climbers who never made it back down. For me, crawling over the remains of those who came before, just to reach a summit, is neither ethical nor sane. Some summits simply aren’t worth it.So, I chose a different kind of Everest – one that would challenge me in ways no mountain ever could. Naked and Afraid tested not just my survival skills, but my vulnerability, my adaptabil-ity, and my sheer will to push forward when everything was stacked against me. It was the ultimate proving ground, and I embraced it fully.RP: You have climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro. You have been on Naked and Afraid. What is your next personal challenge?MH: A documentary team has carefully detailed both my life story and my ascent of Kilimanjaro, and the film is set to be released this year. Preparing for its release is my primary focus right now and, while I can’t share the working title just yet, I will provide more details when the time is right. This project is deeply personal, and I’m hopeful that it will inspire and encourage oth-ers to push past their own perceived limitations.As for Naked and Afraid, my journey with the franchise isn’t necessarily over. The extreme conditions of the challenge landed me in the hospital, forcing me to take a hard look at how much I push my body. Because of the intense weight fluctuations that come with both survival challenges and mountaineering, I may have to consider stepping back from high-altitude climbs to prioritize my long-term health. It’s a difficult decision, and one I’m still weighing. That being said, I would love the opportunity to try again. Survival is about learning, adapting, and pushing forward – and if given the chance, I’d take on the challenge with even greater determination.RP: Are you able to talk about the film you’re working on with Estrada Productions?Mandy Horvath, sitting in solace, looking out on Mt. Kilimanjaro. Photos courtesy of Documentary Team.

19 | SPRING 2025 • ISSUE 3 MH: There is no film currently in the works with Estrada Productions – consider this a teaser for both the upcoming documentary and Na-ked and Afraid. While these productions are unrelated, they are working together in some capacity to include my horse in upcoming op-portunities.Horses have always been a passion of mine, and we have plans to train for barrel racing. One of my dreams is to compete at the Pikes Peak or Bust Rodeo right here in Colorado. It’s an exciting new challenge, and I’m looking forward to seeing where this journey takes us!RP: If you were to write a memoir, what would the title be?MH: Beyond the Tracks: My Journey from Tragedy to Triumph. I will be graduating from the University of Colorado – Colorado Springs (UCCS) with my Bachelors in English and a minor in Anthropology this spring. Special thanks to the anthropology department and those professors who helped me prepare for my challenge on Naked and Afraid.Season premiere, Sunday, March 9, 2025, at 8:00 PM ET. In addition to watching NAKED AND AFRAID on Discovery, viewers can join the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #NakedAndAfraid and following Na-ked and Afraid on Facebook, X, and Instagram. NAKED AND AFRAID is produced for Discovery Channel by Lionsgate Alternative Television and originates from its Renegade 83 label. To learn more about Mandy Horvath, visit her website.Mandy Horvath crying and hugging Julius John White, who helped her on the trail during her climb of Mt. Kilimanjaro.

WISDOMOFTRAUMA.COM A FILM BY Z AYA AND MAURIZIO BENAZZOCAN OUR DEEPEST P AIN BE A DOOR W A Y TO HEALING?featuring DR. GABOR MA TÉWISDOMOFTRAUMA.COMCAN OUR DEEPEST P AIN BE A DOOR W A Y TO HEALING?featuring DR. GABOR MA TÉWISDOMOFTRAUMA.COM A FILM BY Z AYA AND MAURIZIO BENAZZOCAN OUR DEEPEST P AIN BE A DOOR W A Y TO HEALING?featuring DR. GABOR MA TÉTHEWISDOMOFTRAUMA.COMA JOURNEY TO THE ROOT OF HUMAN PAIN AND THE SOURCE OF HEALING,WITH DR. GABOR MATÉ