Return to flip book view

BLACK AT WOODWARDA Special PublicationSIMI AWUJO ’21PAGE 6

1A Special PublicationAn Introduction Rodney HarrisonBlack History at WoodwardBLACK AT WOODWARDA Special PublicationA Note on This Issue This publication was produced by Woodward Academy’s Marketing & Communications Office. While Woodward staff oversaw the production, that work consisted only of creating a platform for the voices you will hear from over the following pages. The contributors were asked to write openly and honestly about their experiences of racism at Woodward and beyond, and about their hopes for Woodward moving forward. Their contributions were not censored in any way, and all contributors had final approval on their pieces before the issue was published.022406261138164030332046Included throughout this publication are excerpts of comments submitted through an online portal, allowing members of the Woodward community to share incidents of racism, either anonymously or by name. Those whose names are included were contacted to request approval to reproduce their comments.Anger/Hope Simi Awujo ’21Black Girl Lorielle Georgetown ’21The N-Word Ban Grace Ross ’21One Voice Nathaniel Johnson ’12The Wound Maya Packer ’22 and Will PackerMake it Right Vicki PalmerA Place of Their Own Lorri HewettHonor Differences Errington Truesdell ’21A Dishonor Anonymous The Work Ahead President Stuart GulleyPhotographs A portrait collage for this issue was created by Gabby Bates ’22 as a special project. Her artist’s statement can be seen on page 15.Illustrations Artwork for this issue was contributed by Gabby Larmond ’21. These pieces were created by them to explore queerness, gender, and the natural world. Their artist’s statement can be seen on page 29.

BLACK AT WOODWARD2On May 25, a police ocer in Minneapolis put his knee on the neck of a handcued Black man for more than eight minutes. As the man begged for his life, the ocer refused to relent. Soon, that man—George Floyd—was dead. In the days that followed, videos of Floyd’s death raced around the world and sparked a reckoning with racism that was felt everywhere. While Floyd was the catalyst for this reckoning, his was far from the only Black life cut tragically short even just this year. Breonna Taylor. Ahmaud Arbery. Rayshard Brooks. The names go on and on.I'm so tired of the stereotypes that follow Black and brown people. Every day, we have to sit back and watch our people be killed for simply being non-white. As a Black parent of four kids, I have to worry about whether my kids will even make it home. My wife and I had to have candid conversations with our kids about how to conduct themselves once they leave our home and how to deal with certain situations if confronted by law enforcement.Every time I watch the video of George Floyd or imagine what Breonna Taylor was going through at the time of her brutal and senseless murder—and what so many of our Black men, women, and children have to face daily, fighting to simply stay alive—I’m deeply saddened and angry. I'm tired of the system that is supposed to protect us continuing to view us as “less than.” Black lives matter not just when we are scoring touchdowns or making athletic plays on the field or court. We matter every day.Being a former professional football player, I am extremely proud of our Black athletes using Black at Woodward, an IntroductionRODNEY HARRISONA screenshot of the Black at Woodward Instagram account, created to share anonymous accounts of racism at Woodward.

3A Special Publicationtheir platform and resources and sacrificing their careers despite the resistance from certain owners to bring awareness and encourage change. However, we can’t do this by ourselves. We need everyone to join in the fight against racial injustice.The Black Lives Matter movement continues to play out in mass protests, but it also created a sense that, for those who have silently suered the pain of racism, now is the moment to speak. To come forward. To be silent no longer.In Atlanta, one way that this came about was through the creation of a series of Instagram accounts relating the anonymous experiences with racism of Black people at the city’s private schools. The Black at Woodward account first posted on June 15, with this submission from a Class of 2020 alum:“Once I wore long cornrows to school and one of my white friends told me I looked like I escaped from prison. I never wore cornrows again.”For those of us who are part of the Woodward community, we watched with shock and a great deal of pain as more posts followed. Hundreds of them. And as the school opened up a form for people to share their stories directly with school leaders, even more came in.Woodward Academy is an institution that has a majority of non-white students—my children among them. It is a place that proclaims diversity as a strength in its mission statement. Woodward reflects the diversity of Atlanta, which is why my wife and I decided to invest in the school with our children's education. But it's also a place that allowed racist sentiment to inflame without enough accountability.For many, I think that these past months have served as an awakening. While you may have thought that racism was a relic of the past—that we had flipped the page on that chapter of history—it in fact is very much alive and present. Of course, if you are Black, you knew this already. Woodward’s failures have left behind a trail of damage—people who were made to feel less than human on account of the color of their skin, and who feel that Woodward as an institution did too little to protect them.In this publication, you will read the stories of some of those people who were hurt and made to feel less than. And you also will read visions and hopes for a path forward in the never-ending work against bigotry and cruelty. It is our hope that this lets all those who have been harmed know that they are heard and recognized. We also hope that it will serve as a starting point for a conversation about what can come next.For those of you reading this who are white, I challenge you. If you truly are interested in joining the fight, you cannot sit back and do nothing. Ask questions. Challenge your beliefs. Protest. Stand with us to fight this system. Use the resources that have been aorded to you by a system of discrimination that has wronged Black and brown people for hundreds of years. I encourage everyone, let your voice be heard. Know that we have a lot of people behind the scenes, myself included, working to make this school a better place for all.The ball is in Woodward’s court. Now is the chance to learn how committed the Academy is to accountability and respect—something this Academy has failed to show in the past. President Stuart Gulley is a good man, and I will continue to support him and his eorts to make this institution the standard for racial equality, transparency, and accountability.As I look back at Woodward’s history, I see the undeniable truth that it was formed as an all male, all white Academy, and that it existed in that form until the late 1960s. For nearly 70 years, neither I nor my children would’ve been welcome here. That is in our DNA. But I also know that Woodward was the first of Atlanta’s private schools to integrate—something the leaders chose to do willingly. Because, ultimately, Woodward is about responsibility and respect. It is about learning to do your best, and to do so in the service of making the world a better place. To not just learn, but to grow as a person. That vision goes all the way back to Col. John Charles Woodward and the school’s founding. That, above all, is the Woodward Way.We don’t need to forge a new identity. We just lost our way. And now, we have our call to action. It’s time to get back on the right path.Galatians 5:22 — But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Rodney Harrison is a current parent of Woodward students and a member of the Academy’s Governing Board. As an NFL player, Harrison was an All-Pro performer with the San Diego Chargers and New England Patriots, winning two Super Bowl rings. Currently, he serves as an NFL TV analyst for NBC.

BLACK AT WOODWARD4

5The first time my son experienced racism was at Woodward. The staff at Woodward North handled it appropriately. I felt they were genuinely saddened by it. I do think more could be done to improve bullying and behavior.ANONYMOUS ALUMNUS AND PARENTA Special Publication

BLACK AT WOODWARD6‘Definitely Anger,but a Lot of Hope’SIMI AWUJO ’21I remember watching the video of Ahmaud Arbery being killed, and then George Floyd. I was just very upset. I didn’t understand. We were already in a very troubled time, and then there were these Black people’s bodies piling up. It started on social media. People posting things. I started posting things.

Simi Awujo taking part in a Black Lives Matter protest over the summer.

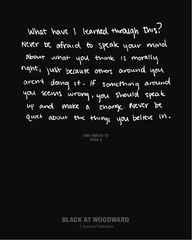

BLACK AT WOODWARD8My friends and I started talking, and we decided we should make posters and go to a protest. Even with coronavirus spreading, I thought it was worth it. Mainly this was Woodward friends. I have two friends who live within 10 minutes. We were the only ones hanging out with each other. We heard that members of Woodward’s Class of 2020 were planning to protest together.My parents were very supportive. My dad was supportive, but he’s a doctor working with coronavirus patients. He made me use a lot of caution. Still, he cared more about the movement than that potential risk. They thought it was good that I was part of a movement in our generation that mimicked one in the past, that I was using my voice to be an advocate for change. It was June 4. We had painted six posters. Three of us went with one of my friend’s fathers. We kept our masks on the whole time even though it was so hot. We marched for four hours till it got dark. We didn’t want to stay out until it got crazy, with the city imposing curfews.We started at Centennial Park, where we met with Woodward friends. We all marched to Ponce de Leon Avenue, chanting and holding up posters. We were posting on Snapchat and Instagram along the way so people could see this was a big deal. I remember going through the BeltLine. We passed people who would look at us and seem judgmental. But it didn’t matter. It was a movement.I didn’t even know where we were, just moving through Atlanta, and then we ended up back at Centennial Park. We talked to people we’d never met about everything going on, their experiences. We talked to other people from Woodward. It was good to see so many people out, no matter their race, supporting the movement. There was definitely anger, but there was a lot of hope. Because of the coronavirus, we didn’t protest again. We were trapped in our homes, and we were taking to social media to interact, and so much information was coming out. It helped everyone learn about these terrible things happening to Black people. I was learning more, and I just didn’t understand how people could truly hurt someone like that. Take away someone’s life so simply. How can you not support a movement that just says Black people’s lives matter? How can you dismiss it by saying that all lives matter? No one said all lives didn’t matter. The issue is that Black people are being killed.It also was frustrating because there were people I knew who didn’t post anything to support the movement. There were people posting hurtful things, things about Black on Black crime statistics, as if that changes the fact that police are killing Black people. But then there were people of all races at Woodward who would go on group chats and say that they couldn’t understand what Black students are experiencing, but they would express their support. They know they don’t have to deal with this problem, but they stand with the movement.When the Black at Woodward posts started to appear, I was honestly very surprised, which is weird. I’ve been at Woodward since kindergarten. I’ve probably experienced stu when I was younger that I brushed o as normal.One thing I remember, I have a Black friend who hung out with white girls, and everyone called her an Oreo. And we all thought it was a joke, and looking back on it, that was probably the beginning of us separating races. What it is to act white and to act Black. Really, we’re all just people. We were young and thought it was funny, but we were dierentiating and driving a wedge.At Woodward, I’m part of the Black Student Union, and I try to educate people who say something ignorant. I’ve been signing petitions and sharing things on Instagram stories. Making sure everyone is registered to vote who is old enough, to exercise their rights as American citizens.What have I learned through this? Never be afraid to speak your mind about what you think is morally right, just because others around you aren’t doing it. If something around you seems wrong, you should speak up and make a change. Never be quiet about the things you believe in.

9We are humbled and honored to be enrolled in an institution that is unafraid of acknowledging that some of us have been exposed to the horrors of racism merely by being born in a different skin. Our family supports the Black Lives Matter movement. Non-violent awareness is critical. Histories of all walks of life keep us all on our toes, engaged, and able to work together to dismantle the tragedy of Black slavery and oppression in America. We don’t believe that this means all lives don’t matter. But some of our lives are under a constant state of threat by merely being brown and walking out of our front door.ANONYMOUS PARENT

10Woodward students self-segregate by race. Because my child is mixed race, she is often left in the middle and faces racism from both sides. When she started at Woodward, she attempted to become friends with white students—they wanted nothing to do with her. She became friends with a group of Black students. My child is friends with a white student who is largely rejected by my daughter’s Black friends. When I asked her if she thought they were not open to this other student because she is white, she thought about it, reflected, and then said, “Yes, race is definitely a factor.” I was impressed with her honesty but saddened by the answer.ANONYMOUS PARENT

11This summer, Black students from around the nation spoke out against instances of racism and mistreatment they faced at educational institutions. Woodward students were no exception to this fact; they, too, courageously shared their personal experiences on an anonymous Black at Woodward Instagram account.In response to these stories, the administration implemented new policies in order to grow the No Place for Hate campaign and help students of color feel safer and more welcome at school. Our president, Dr. Stuart Gulley, announced one of these new implementations: banning the use of the n-word. “The task force is developing a hate speech policy [page 12], which we will share with you in greater detail once we have finalized our work on it,” Gulley said. “However, one part of the policy that we already have finalized is that the use of the n-word will be permanently banned on campus, by any and all students, regardless of race.”The n-word is a racial slur that derives from the Spanish word for black, but later became a derogatory term used to marginalize and dehumanize people of African descent within America. Although the use of hate speech has been a topic of discussion through school-wide panels and Black Student Union discussions, there still has been consistent use of the word by a number of students on campus. “Between the Black at Woodward Instagram account and the Google Form that we set up where people could communicate directly to us and anonymously, we received more than 600 communications,” Gulley said. “The vast majority of those communications were complaints, mostly about the use of the n-word by students with each other, and the perception that we knew about it, and didn’t do anything about it.”The policy sparked conversation among students and teachers, one being Elizabeth Burbridge, social studies and multicultural, ethnic, and diversity studies teacher. “I think if we are talking from a point of view that school is a professional space where we shouldn’t be using profanity, and that the n-word is counted, even when used by Black people, that makes sense,” Burbridge said. “However, I think by acting like the use of the n-word by white people and Black people is the same, that’s where it’s problematic.” Lorielle Georgetown ’21, marketing director of the Black Student Union (BSU), feels that the n-word ban is a step in the right direction. “I think that the choice to use the n-word is totally up to Black TheN-WordBanGRACE ROSS ’21A Special Publication

BLACK AT WOODWARD12Woodward’s Hate Speech PolicyRacist or Inappropriate Language: We are committed to providing an environment that is free of discrimination or harassment of any kind, whether based on gender, sex, age, race, color, religion, national origin, disability, or any other identity marker, as well as ideologies or political views. We do not tolerate any actions, words, jokes, notes, emails, social media, or videos of a demeaning nature, regardless of intent.Students oending the policy are subject to the school disciplinary system and will receive detention hours. Repeat oenders may be referred to the Discipline Board for increased consequences including the potential for dismissal.Hate Speech: At Woodward Academy, hate speech is defined as abusive or threatening speech or writing that encourages violence toward a person or group, especially on the basis of their race, religion, or sexual orientation.Under this policy, Woodward will apply the following “Two Strike” procedure:First Oense:• parental notification• detention hours• Saturday training on racism & diversitySecond Oense: Referral to Discipline Board A student should report hate speech by another student to the Dean of Students, Assistant Principal, or Principal and must provide documentation for the charge.A student should report hate speech by a faculty member to the Principal and must provide documentation for the charge.Woodward reserves the right, in its sole discretion, to proceed directly to a Discipline Board referral if the First Oense is deemed to be particularly egregious or harmful in the judgment of the Administration.students and individuals. However, I believe that certain institutions should have the right to make decisions about what they want their students to represent,” Georgetown said. “I think that it was a good decision because the lines become so gray when we talk about use of the n-word, and who can and can’t use it. I think deciding that all students can’t use it is a reasonable thing to do considering the situation we are in right now.”Grace Mitchell ’21, operations manager for the Black Student Union, has concerns about the new policy, though. “I understand why they are banning the n-word, but it is not right for [the] administration to say that this one group can’t use this word when there is so much history behind it, especially in the Black community,” Mitchell said.The task force is not simply banning the word, however; they also have plans to educate students and faculty on the history behind the hate speech and its implications.“It is not just a matter of saying, ‘You can’t use this word,’” Gulley said. “There will be an eort to address the history of the word, why it is so hurtful, and why we feel it’s important it’s not being used.” Another way of becoming more educated on current issues, according to Georgetown, is for students of all races, religions, and genders to attend BSU and Intersectional Feminism Club meetings.“Woodward’s [diversity] is a perfect way to get exposure. You can either use this experience negatively or you can use it positively,” Georgetown said. “Using it positively would be becoming enlightened about the issues that Black students, Muslim students, women [and more] face on campus.”Beyond the hate speech policy, the task force is taking other steps in response to the feedback they received over the summer. One of these steps is the new whistleblower policy.“[The] whistleblower policy is [so] faculty and students can go and anonymously report any instance of racism, discrimination, hate, or bullying that they believe they have experienced or witnessed,” Gulley said.All in all, it is important that non-Black students, faculty, and administrators understand that there is simply no excuse for using such crude, racist terminology.“White people can’t say the n-word. It’s okay to tell white people they can’t say the n-word,” Burbridge said. “That’s okay.” Grace Ross is a senior at Woodward. This article originally appeared in The Butterknife, the student newsletter.

13A Special Publication

15I’ve created this piece made from portraits of Woodward Academy Upper School students so that the conversation of what Black students experience at predominantly white private schools can be shared through art. I want to inspire young Black students at Woodward to see themselves as enough and valued because they are enough and should always be enough, and never belittled into thinking that they are not. My piece comes from asking myself what my experiences have been like at Woodward as a Black female student, and what I can do to reach out of my areas of comfort. I used alternative processes to create my piece. I normally would have taken portraits and mounted them onto a piece of paper and called it a day. But I wanted to use an alternative process because it challenged me to do something I was unfamiliar with doing. To overcome my shyness, I photographed students I know and didn’t know—so that I could gain confidence in being professional when taking pictures. Each of the students were photographed with their masks on because of the pandemic. I wanted to ensure the safety of the students even if it was not an ideal choice for me, since I was taking portraits. “You Are Enough”GABBY BATES ’22Top Row (left to right): Oliviah Matthews ’24, Corey Fuller ’22, Haley Fuller ’21, Robert Thomas ’21.Bottom Row (left to right): Vashti Hobson ’22, Wes Craig ’23, Nico Coleman ’24, River Hanson ’23, Laine McDaniel ’23.

BLACK AT WOODWARD16THE WOUND THAT MUST BE HEALEDWILL PACKER & MAYA PACKER ’22

17A Special PublicationMaya Packer is a junior at Woodward and is the president of her class and co-chair of the Black Student Union. Her father, Will Packer, is a producer of dozens of films (including Straight Outta Compton, Stomp the Yard, and Ride Along) that have grossed more than $1 billion worldwide at the box oce. This is a conversation they had about race and racism in this tumultuous year, about the Black at Woodward movement, and about the path forward, both for Woodward and the nation.Will Packer: As you know, I went to a predominantly white school. Mine had even fewer African-American students than Woodward has. One of the things that is consistent about being a minority in these spaces: You’re constantly trying to look for validation, trying to feel heard, feel seen, feel important. If the system is not going out of its way to make sure you feel heard and seen, sometimes it can unintentionally do things that make you feel suppressed. I was someone who always fought through that. I fought through that in my involvement in the school, in extra-curricular activities. I ultimately participated in student government and became student body president, I played athletics, and I was at the top of my class. But I felt the need to do that. Number one, it was instilled in me by my parents, but number two, because I was one of the few African-Americans both in the school and in my AP and Honors classes as well as student government. I felt the need to not only make my presence felt, but to represent. Represent for folks that looked like me who didn’t have a voice in those spaces. So I was driven to do that. I don’t know if you feel the same need.Maya Packer: Going o of that idea of getting involved and using that to fight the suppression, I do think that I’m in a lot of spaces of leadership: class president, co-chair of Black Student Union, I write for The Blade, and I have good relationships with the administration and a lot of faculty members. So as a result, I’ve kind of become the “special Black girl,” and I notice the way that I’m treated isn’t the same as my other Black female friends who aren’t necessarily in the same positions as me. I notice that they get more of the stereotypes of ghetto, loud, and rambunctious. They get more disciplinary action taken against them. I’m not saying that I don’t still experience that side of Woodward, but it feels like, “You’re special, you’re dierent, you’re not like ‘those’ Black people.” From what you’ve told me from your experience in high school, it sounds kind of similar. I know that you had really good relationships with your classmates and your teachers, even though some of them might’ve been racist. But they liked you because you were charismatic, outgoing, and funny. I think the idea of tokenism goes beyond even just Woodward using pictures of Black people to promote diversity on the website, and goes even further into lifting up certain Black people while forgetting about all the other Black people and then calling it equity, calling it diversity, calling it equal when it’s not the same experience for all Black students.Will: Woodward is really this microcosm of America, of our society, right? Systems of power cede nothing without demand. So, when you’re in power, you’re always trying to preserve the power that you have. One of the ways to do that is to make it seem like you’re being equitable and fair to minority groups when you’re really not. To say, “We will let in a select amount of folks from the minority group.” Right now we’re talking about Black people, but this applies to Latinos, this applies to LGBTQ folks, this applies to anybody in a disenfranchised group. You let a few through, you let a few have success, you let a few be representative of that larger group, and then you can say, “See, we don’t have a racial problem, look at Maya Packer, look at Will Packer.” But the reality is that there would be a lot more Maya Packers and Will Packers if more opportunities were there, and were the playing field totally equal and fair. The thing that systems have to recognize is that Woodward will be a better institution—a world-class institution that can compete with anybody, anywhere—if it is more diverse at every level, from the administration

BLACK AT WOODWARD18to student leadership to sta. If it is more diverse, it will be better because you will have a diversity of thought and perspectives, and you will be able to compete at the highest level. You show me any entity that has one type of person, one way of thinking, and I will tell you it is a flawed entity that will be beaten by one that has multiple ways of thinking and multiple perspectives.Maya: From the perspective of being one of the only Black people at your high school, do you look at Woodward and say, “This is great, look at all these Black people, look at the positions that Black people are in in this school,” and think I have it great compared to what you went through?Will: I think you have it better. I wouldn’t say you have it great. I look at Woodward and say, “Woodward is far more progressive than St. Pete High School,” where I went. But that doesn’t mean that Woodward can’t do better. You can always do better, and you should be striving to do better, especially when it comes to social justice and racial inequality. Malcolm X has a great quote, it goes: “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress. If you pull it all the way out, that’s not progress. The progress is healing the wound that the blow made. They haven’t pulled the knife out; they won’t even admit that it’s there.” We’re in a society that, certainly before 2020, did not want to admit that there was even a knife, and in some aspects, still don’t want to admit it. But with all the cataclysmic events that happened this year, there’s no question that Woodward, Hollywood—where I work—the White House, state governments, police departments, nobody can act as if we don’t have a problem in this country. This country was built on inequality. The fact that you and I are even having this conversation to be published to the Woodward community at large is a positive thing because the majority of the people who will read this do not look like me and you. And they probably wouldn’t get this perspective were it not for someone at Woodward intentionally saying, “Let’s allow these voices to be amplified because we haven’t done enough of that.” That’s a good thing. That matters. Maya: Yeah, I definitely applaud their eorts and I think it’s very important work that they’re doing. The moment that we’re in right now, it’s unacceptable to not be doing something to be more diverse, be more anti-racist, be more inclusive. So, being on the board of the Black Student Union, I’ve seen firsthand what the Anti-Racism Task Force is doing, and what the administration has been up to, and their attempts to fix the broken system at Woodward. But also, from a student perspective, I think we’ve gotten a little sedentary. I think the racial tensions have kind of died down, and I haven’t really seen any new changes from Woodward happening. Hopefully that’s just because they’re happening behind the scenes, and it’s slow work. I’m looking forward to seeing the actual long-term eects of this turnover that they’re doing right now. Now, I have a question for you: Did you decide to go to a historically Black university because you were tired of being the only Black person in your Honors classes, or because you were tired of being the only Black person in a predominantly white institution?Will: No, I didn’t. I honestly looked at an HBCU and didn’t think it was competitive enough. I thought that I needed to be going to an Ivy, because I had Ivy League credentials. I had the grades and the test scores to get into an Ivy, and that’s where I planned to go. Every high school in my hometown had a similar racial makeup, so I didn’t know any dierent. Even though my parents exposed me to HBCUs, it wasn’t an environment that I felt like I could thrive in. Ultimately, I went to Florida A&M because there was someone who was forward thinking at the university who said, “We’re going to get the highest achieving African-American high school students in the country, and we’re going to go after them,” in the same way that D1 athletic powers go after athletes. The top National Achievement scholars were going to Harvard. The top scoring Black students on the SAT were going to Harvard. FAMU, where I ultimately went to school, made a big push and got money from the corporate community to oer merit-based scholarships to high achieving African-Americans, and I got one of those. It was the best decision ever. See, I was like you. I was one of few high achieving Black kids in my school, so I actually used that to my advantage because I had everybody’s attention. That was something my parents encouraged. They said, “You’ve got everybody’s attention, you stand out dierently than the other kids in your class, so take advantage of that.” And I did. I’m somebody who thrives in that kind of environment, and I never gave that attention up. Well, when I went to FAMU, I was with a whole school of high-achieving Black folks, and I had to do something else to stand out. See, I could impress white people who underestimated me. That was easy. My whole life, I had been exceeding the expectations of white people who

19A Special Publicationwere shocked at what I could do, and I used that to my advantage. When I got to an HBCU, no such advantage could be taken there.Maya: That makes me wonder, you know, all the white teachers who give me high praise, is it because they’re underestimating me, or is it really warranted? And as my Dad, you’re gonna say, “It’s really warranted,” but that just made me think.Will: Well, I think you’re high achieving, but that doesn’t mean that other people see it from the same perspective. Look, you want teachers who will push you. You want teachers who will value you, but push you to be the best you can be. I don’t know the answer to that question. If they haven’t come across high-achieving Black students, they may not expect as much from you. That’s not right, they shouldn’t be that way, but that’s just a human thing, not a teacher thing. We gotta make it so that the Mayas and Wills are no longer such a minority and such a rarity. That’s the reality, because there’s somebody out there who’s way smarter than you, way more adept than you, will work harder than you, and the same for me, but who hasn’t had the same opportunities. We gotta get them into the conversation.How do you feel that Woodward does in terms of race relations amongst the students?Maya: I think that the reform of the system is easier for the administration to do than the reform of their students. They have control over their teachers, their curriculum, all of that, but when it comes down to the mindsets of individual students, they can’t really control that, and they can’t really control the households and environments that these kids are being raised in. So, I think that even though Woodward is putting forth change within their system, I don’t know that it’s reaching students in a way that would change a potentially racist student’s perspective on race. A lot of the students in my class who have said some controversial statements and opinions when it comes to race—they’ve been in the Woodward environment their whole life. So, if they get in on the ground floor to instill their values of diversity, inclusion, and equity while the kids are still young and continue it through high school, then I think that they have a fighting chance to change the environment. But as of right now, for kids my age, it’s kind of too late. There definitely can be reform and change, but realistically, people are set in their ways. Even if Woodward cracks down on their tolerance of those students and their actions, it’s still there. We’re still enduring it outside of school and on social media.Will: Yes, but Woodward has a big responsibility to its students. It’s about the culture created there, and it’s about starting it very early. Sure, you can’t control what’s going on in someone’s house, but you can control an environment that allows racist and dangerous perspectives and thoughts to fester. And the school has a responsibility to make this, A: a safe environment for everybody, and B: an environment that teaches everybody what being anti-racist means. A lot of times you have a system and a school like Woodward, and they don’t even realize that they’re helping to foster some of these dangerous ideologies by simply not cracking down on them, by not calling them out. So much of the challenge when it comes to social justice is the fact that we don’t want to admit that a lot has been done wrong. People don’t want to admit that, because they want to hide from the blame. Nobody wants to get the blame, nobody wants to say that this country or this school has failed on certain levels. The reality is that it has. The sooner you can admit it and call it out, the better you’ll be for it. We gotta stop running from our past. To your point about the individual students, you’re 100 percent right. However, there’s a huge responsibility on the school to make sure that the culture of the school is one that is truly inclusive and progressive. It starts from the very top, it’s led “The thing that systems have to recognize is that Woodward will be a better institution—a world-class institution that can compete with anybody, anywhere— if it is more diverse at every level...”

BLACK AT WOODWARD20by example and what you see in the administration, and the faculty, and the sta, and in the culture that is allowed there.Maya: I don’t think that I’ll see a substantial change in the Woodward culture within my next two years here, but I’m excited to be able to look back, in the future, and see how the next generation benefits from the current movement that Woodward is participating in. Will: I think that’s well said, Maya. There’s a lot of work yet to be done. However, the fact that we’re having this conversation that’s being amplified by Woodward, the fact that you’re in the position that you’re in and are able to give voice to students that otherwise wouldn’t have it, the student population and demographics of Woodward are more diverse now than they were 10, 15, 20 years ago, are all positive things. Positive indications that we’re trending in the right direction. There is still a ton of work left, and Woodward is no dierent than many of the institutions around this country. What we need are allies. Allies that don’t look like you and me. It’s not your problem to fix. It’s the people who are in power and who are benefitting from the system. It’s their burden to fix it. And we need allies who are in the system and benefit from the system to say this is not okay and we can do better. Woodward has a long way to go, but I am emboldened by the trends that I see that are moving in the right direction. ‘A Dishonor Not to be Truthful About Racism’ANONYMOUS, CLASS OF 2010I was deeply disturbed and disheartened to see current students, alumni, and former sta members share their accounts of blatant racism on the Black at Woodward Instagram page. Frankly speaking, the fact that these occurrences are not atypical and span across decades can be described only as a crisis, and it highlights the racial injustices that are a part of the culture at Woodward Academy. This has to end today. By not expelling students and firing sta who inflict racist aggressions against their peers, the Academy is complicit in racism, period. This is intolerable and insuerable. There are multiple accounts of students being called the n-word or suering from racial microaggressions from students and sta members alike. There are various accounts from current students that detail racist attacks with no justice or repercussions, despite escalating these issues to administration. Schools should be safe from emotional, spiritual, and physical violence. I personally have suered from similar microaggressions and have other Black and POC classmates who have stories to tell.Initially, seeing people share their stories on the Instagram page did not shock me; but what came as a surprise later was the sudden influx of many traumatic memories of my time at Woodward that I had suppressed. As a student, I remember vividly reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and other literary works strewn with the n-word. When asked to read aloud in class, my white classmates saw no

21A Special Publicationissue in saying this slur, oftentimes not corrected by teachers. On Obama’s Inauguration Day, a teacher came to class dressed all in black, stating that she was in mourning. I had a white classmate who wore a Confederate belt buckle and told me that his family probably owned mine as slaves. I had a teacher call our class (white, Black, and POC) “cotton-pickin’, finger-lickin’ somethings” during moments of frustration. When I revisited these memories, my initial thought was, why didn’t I speak up or tell my parents? I started to have overwhelming feelings of shame and guilt, but I had to quickly tell myself—and I hope all those in the same situation can understand—the responsibility isn’t on the victim, but the aggressor. It is not my responsibility as a Black woman to tell racists that they are racist. It is unacceptable for a classmate to be allowed to wear belt buckles with the Confederate flag. It is unacceptable for a teacher to refer to anyone as cotton pickin’ and finger lickin’. It is unacceptable for a teacher to refer to the inauguration of the first Black president as something to be mourned. It is harmful and reckless for English teachers not to explain why the use of the n-word is a vicious racial slur and is wrong. If students are required to read books like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for class, there needs to be mandatory reading by Black authors explaining the true meaning behind this racial slur and its harmful legacy in the United States. And the slur should not be tolerated to be read aloud or used, to start. There are countless classics by Black authors that hold equal or higher literary power that were not covered during my time at Woodward in any English class, and I believe that needs to be changed immediately. These books should be included in the regular curriculum and not just as a highlight and glossed over during Black History Month. (Suggested reading list included at right.) Additionally, Black history should be included in the regular curriculum. It is not enough to educate students on the Civil Rights era as a gloss over of the 1960s, or to touch on slavery as written in the history books. Because, as educated and aware people, we know that history books are written by revisionists who downplay how deeply rooted racism is in this country. My parents were alive during the Jim Crow era; my grandparents are alive to tell me stories of segregation and racism. We are not removed from these realities. It is a dishonor not to be truthful about racism. President Gulley stated that 54 percent of students are people of color, and 34 percent of sta members are people of color, but I would like to see the numbers of Black students and sta members increase. There needs to be a scholarship fund for Black students specifically as a way to increase educational opportunity in the Black community. This scholarship fund should include tuition and fees, books, uniforms, and transportation. Woodward Academy has a tremendous endowment and countless donors who should have no issue into contributing to said fund. Should Woodward receive pushback, reconsider accepting donations from these individuals in an eort to stand in solidarity with your Black community. I have seen the children of rich white parents and donors get away with things that Black and POC students could never, and that culture must end. If the Academy cannot put their money where their mouth is, it must reevaluate if it is actually a No Place for Hate school. Book Recommendations • Native Son by Richard Wright • White Fragility: Why it’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo • Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower by Brittney Cooper • White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color by Ruby Hamad• Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race by Beverly Daniel Tatum, Ph.D.• Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 by Scott Ellsworth• In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose by Alice Walker• The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness by Michelle Alexander• Such a Fun Age by Kiley Reid• Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge Danticat I look forward to the results of the assessment of the curriculum, revision of the student handbook, and changes to be made following the listening sessions. I believe alumni are entitled to that information so that we can create change and hold the administration accountable moving forward. Enough is enough.

22OVERT AND COVERT RACISM WAS BAKED INTO THE CULTURE AT WOODWARD AND WAS REINFORCED BY THE FACULTY WHO ALLOWED THIS PERVASIVE RACISM TO EXIST. ALTHOUGH THERE WERE SOME GREAT TEACHERS WHO PUSHED ME IN MY OWN THINKING AND HELPED ME EXCEL ACADEMICALLY, THERE WERE ALSO A NUMBER OF TEACHERS WHO DISCOURAGED ME AND MADE ME SECOND GUESS MYSELF. ANONYMOUS ALUMNUS

23A Special Publication

BLACK AT WOODWARD24Black History at WoodwardIn 1900, when Georgia Military Academy opened its doors, the first 30 students were homogenous—they were white, and they were male. This eectively remained the case for the following decades (some students came from Cuba in the 1920s and 1930s) In the transition from GMA to Woodward Academy, the school began admitting girls in the mid 1960s and then admitted its first Black students in 1971. Woodward was the first Atlanta private school to integrate, but that fact does nothing to diminish the exclusion of the previous 70 years.1900Georgia Military Academy is Founded19 74First Board MemberWilliam (Bill) Allison is the first Black person named to Woodward’s Governing Board.1975First TeacherMarva Massey joins the Lower School as a PE teacher, becoming Woodward’s first Black faculty member. Two years later, Helen Spears joins the sta as a media reading teacher.1983First Senior Class PresidentDarrin Finney ’83 is named the first Black senior class president.

25A Special Publication* Homecoming King records are incomplete, making it impossible to say for certain who the first Black Homecoming King was.GMA Becomes Woodward Academy1988First ValedictorianTamara Jones ’88 becomes Woodward’s first Black valedictorian. She now serves on the Governing Board.197319711990First Homecoming Queen*Valaurie Bridges Lee ’90 is voted Woodward’s first Black Homecoming Queen. She now serves on the Black Alumni Association’s Advisory Board.1993First Student Government Association PresidentTorrance Mosley ’94 is elected the first Black president of the Student Government Association.1967Woodward IntegratesDuring the 1971-1972 school year, four Black students enroll: Darlene Douglas ’73, Melodie Ricks ’73, Clarence Davis ’74, and Robert Ricks.First GraduatesDarlene Douglas and Melodie Ricks become the first Black students to graduate from Woodward.

BLACK AT WOODWARD26‘I Have Never Taken a Class Taught by a Black Teacher’LORIELLE GEORGETOWN ’21

27A Special PublicationBlack girl, non-Black classroom; Black girl feels unheard and unseen. Black girl, silent while her classmates assume;Black girl, angry as she feels like another number in the machine. Black women everywhere are under immense pressure to stay strong amidst police shootings and harsh criminal sentencing. In a world where the targeting of Black people is on national television and social media, I look forward to the remodeling of institutions worldwide, especially as Black women everywhere are making history politically and economically. As the nation continues to grow and become more inclusive, I look to Woodward Academy to serve as a microcosm of this growth. While Woodward has one of the most ethnically diverse campuses in Atlanta, my experience as a Black girl has not been everything I hoped it would be. As outspoken as I am, I have developed a state of silence. The emotional trauma and distress of debating non-Black people about topics like armative action and cultural appropriation are too much to bear. Unfortunately, my intellectual understanding of Black issues does not come from the Woodward classroom. While the Woodward curriculum does include works by Black authors, these pieces of literature are a small fraction of the required readings. During my time at Woodward, I have read three books and a handful of pieces of civil rights poetry written by Black authors. The standard argument against my perspective is that authors like Shakespeare wrote “classics” that students must study. While I understand this argument, it supports a white-washed perspective of literature that I just cannot arm. On the whole, I look forward to the results of the comprehensive curriculum review by the Anti-Racism Task Force.Another negatively transformative factor in my educational growth has been the lack of demographic diversity in Woodward’s faculty. During my time at Woodward, I have never taken a class taught by a Black teacher. Fortunately, I have had the opportunity to seek connections with Woodward’s Black faculty through the various clubs and organizations on campus. Through the Black Student Union and Legal Studies Club, I have observed presentations by successful Black adults in multiple fields. As I graduate in the spring, I hope that these clubs continue to introduce students to thriving Black adults.Despite the reality of the past, Woodward’s willingness to grow is inspiring. While I did not find the Black at Woodward Instagram posts surprising, I did find joy in the administration’s response. I have attended multiple independent schools in Atlanta, but none compare to the Woodward Academy community. We are a wave of energy, school-spirit, and diversity. Not only do our students love their classes, but they love their cocurricular activities. Our administration realizes that Woodward has work to do. As policies become more inclusive and the administration becomes more understanding, I hope for an atmosphere that does not focus on social division, but rather positively embraces diversity. With persistence, Woodward will be a community where students, especially in the Black community, feel safe and loved. This growth is possible. As clubs and organizations like the Black Student Union host dialogue with principals and deans more often, I encourage students to continue to reach out to our administration. I hope student leaders will stay involved in the transformation of the Woodward community. This continued connection and commitment to inclusion and transparency will help Woodward go from being the most diverse school in Atlanta to priding itself on being the most inclusive.

BLACK AT WOODWARD28

29A Special PublicationGABBY LARMOND ’21I am an interdisciplinary visual artist based in Atlanta, Georgia. My work centers around the exploration of queerness, gender, and the natural world, with emphasis on color and mark making. Through my art, I wish to understand myself and the world around me whilst projecting my own experiences onto a physical form. My artwork takes a critical view of social, political, and cultural issues through self-reflection and portraiture across various mediums—the most recent being acrylic paints and gouache. The subject matter of each body of work lends itself to various materials and the forms including painting, film photography, drawing, and mixed media and often manifest into a variety of self portraits. With influences as diverse as John Dugdale and Richard Avedon, new insights are created from both explicit and implicit discourse. My works are characterized by the use of bright colors and playful juxtaposition. With a strong interest in portraiture, I often create work that depicts a variety of narratives, often serving as a commentary on society and pop culture in reference to social issues such as LGBTQ rights, climate change, and gender identity. Each piece begins as an idea, plays into a carefully crafted concept, and is executed in the medium that serves the concept best. The results are deconstructed to the extent that meaning is shifted and possible interpretation becomes multifaceted, allowing viewers to project their own unique interpretations onto each piece. Gabby Larmond has participated in the Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards, winning a Gold Key in the Southeast region in 2016 and 2017, and has been recognized in the 2020 Atlanta Celebrates Photography Exhibition. In 2019, they graduated from the Oxbow School’s 41st semester.“Starchild”

BLACK AT WOODWARD30A Place to FeelConnectedand SupportedLORRI HEWETT

A Special Publication31For many years, Woodward Academy held the position that anity groups were potentially divisive, and that they would not be allowed in our Upper School. Several teachers and students over the years attempted to create a Black anity group, but the request was always refused. This is the story of how the Unity Club, an informal, unspoken organization started by students, became our Black Student Union in 2016.One day back in September of 2016, a few of my students asked me if they could meet in my room during a lunch period and talk about issues of concern for them. I knew them all; I had taught them the previous year. What they all had in common was they were African-American, and my room was a place where they felt safe to be themselves and speak openly about their concerns. I grew up in an all-white community, and I’ve always been sensitive to the isolation students feel when they are the only person of color in a class. I wanted to make sure my students, even in our wonderfully diverse community, felt connected and supported.The next time we met, I had about 18 African-American students in my room during lunch. We talked that day about how nice it was to talk in a group where they didn’t have to explain their perspectives as people of color. They could just be themselves. I can’t remember the subject of that first meeting. I just recall the sense of comfort the students felt. I want all of my students, no matter their background, to feel comfortable in my room. Even so, I was so happy that I could give these students this space. The next meeting I ordered pizza, and we had about 25 kids—mostly 11th and 12th graders. This time, they had a lively discussion about how Black boys and girls perceive each other. They talked about how negative social stereotypes aect dating relationships, and how dicult it can be to navigate those relationships. I mainly listened, as did a pair of new-to-Woodward twins whom I had invited so that they could meet other Black students. It was great to listen to kids talk about issues that mattered to them—intra-racial issues that they didn’t typically get to discuss at school.We had outgrown my classroom by meeting number four. We met in A240 for our lunch meeting two weeks later. I was happy to see that the word had gotten around. More younger students were there. This time, students wanted to talk about microaggressions they had experienced here at Woodward. One by one, students stood up and talked about experiences with peers, even faculty, where a well- (or sometimes not-so-well-) intentioned statement went wrong. After each student spoke, I saw how they responded to each other—with nods, yesses, and “I dealt with that, too!”s. But it wasn’t a complaining session.

BLACK AT WOODWARD32Leila Sampson ’17 (currently a student at Spelman), who had been named the president of the group by her peers, asked students how they can respond to these comments in a positive way. I found her attitude really admirable. Instead of getting angry, students encouraged each other to be proactive.I grew up knowing that I was a “pioneer” of sorts; often, I was the only African-American person my peers, neighbors, and teachers knew. It was an undue burden, but I chose to be a positive representative of Black culture. It was tough. I often resented being called on in class (during Black History Month, usually) to be the spokesperson for “Black experience” or “the African-American perspective.” Our students of color at Woodward have more of a community than I had, but they remain pioneers—they are often judged by the actions of others, just because of their skin color. This burden is more easily borne with the understanding and fellowship of others. I’m glad I can help spare my students some of the loneliness and isolation I felt at their age. That’s why I’m so passionate about sponsoring this group, and why I’ve tried to be as helpful to the students as I can be.The following meeting occurred on the day after the 2016 election: Several students came to my room and cried in my arms. I cried, too. After all, I shared their fears. We had planned to discuss colorism in the Black community that day, and we continued with our plans. But we also gave students a chance to discuss their feelings about the election in company. I think the students left the meeting feeling, if not better, then more resolved. I know I did.We had an ocial club by then. We saw 40-60 students at our meetings, and we had students who had stepped forward to be leaders. We had a leadership meeting later in the month for the students to think about what they wanted this group to be. What role could this group play in the Woodward community? To get ideas from the perspective of a sponsor, I began inviting other faculty members to sit in on our meetings and give me their insights. I got so much positive feedback from my peers here at Woodward, from fellow teachers at the annual NAIS People of Color Conference, and from fellow teachers at independent schools in Atlanta. I also heard from parents of our group members, thanking me for facilitating this group for their children.Our club could become ocial, and the hard work the students had put into creating the club could be celebrated publicly. The Unity Club became the BSU, the Black Student Union, which is still thriving today. Our students plan educational and social events for their peers and create programming for the Upper School during Black History Month. We have had panels discussing the n-word and its eects, discussions about attending HBCUs vs primarily white institutions for college, Freestyle Fridays, potluck luncheons, Black history trivia games, guest speakers, presentations on systemic racism, and even make-up seminars for a variety of skin tones.This is a group where students can make new friends and join together with the comfort of knowing that they have shared experiences that don’t need explanation. The BSU has become a force of goodwill on this campus, and we have become one of the largest active student organizations.This summer, I worked with our new leadership, Maya Packer ’22 and Alexis Rogers ’21, who wanted to address the Black at Woodward Instagram posts. While the pandemic has certainly aected our ability to meet in person, the club continues in full force this year. We have held a listening session with the Upper School principals and deans so that students could discuss some of the concerns that came up on the Instagram page, and I was gratified to see the enthusiasm that our Upper School leadership showed in supporting our students.This club is very special to me. It gladdens my heart to see students come together with their peers in a way that I wasn’t able to when I was in high school. I appreciate that I work at a school where the leadership is willing to adapt to change, and to give support to students with diverse backgrounds. This work is ongoing, but I feel confident that Woodward is doing its part to build a more inclusive community. Lorri Hewett is an English teacher in the Upper School at Woodward. She holds a BA from Emory University and an MFA from the University of Iowa. She is the author of several novels, including Dancer, about a Black ballet dancer.

33A Special PublicationRespect and Honor DifferencesERRINGTON TRUESDELL ’21Woodward Academy is the only school I have known. I entered Woodward North at age 4 and made the transition to Main Campus for seventh grade. I recall my time at Woodward North being carefree, nurturing, and inclusive. It was academically competitive, but I thrived in every way. I was definitely a minority at North, since the total number of Black male students in any grade could be counted on one hand. Nevertheless, I felt extremely comfortable and appreciated as an individual. I was awarded the highest honor at North—the Woodward Way Award—given to one member of the sixth grade class who embodies “all things Woodward.” I don’t recall any direct experience with racism at North, but I suspect that racism is dicult to discern at such a young age. If it existed, it definitely took a backseat to our optimism and innocence. My Middle School and Upper School years have not personally been marked by racially motivated situations, but my family was forced to deal with a specific incident when my sister, who graduated from Woodward in 2018, was in eighth grade. I was a fifth-grader at the time.

34 BLACK AT WOODWARDIt involved racially explicit internet postings by some of her white male classmates. The postings were brought to my parents’ attention by the parents of my sister’s classmate, who also was a close friend—this was a white family disturbed by the images that were circulating amongst students. Eventually, the images were brought to the attention of the teachers and the administration at the highest level. I have a vague memory of this time and incident. My parents limited my exposure because of the potentially negative impact on me.It was extremely upsetting to my sister and my parents, who considered withdrawing us from Woodward because of the incident. The issue was resolved to the satisfaction of my parents, and my sister did complete her education at Woodward without any other issues. She felt very comfortable and supported during and after the incident. My final years in high school have seen an escalation in the attention to racial tensions. These issues clearly have been a problem in the past but are being brought to attention by the proliferation of social media and the collective voices of people who can no longer ignore the impact of racial disparities on access to opportunities. When I first saw the Black at Woodward Instagram posts, I was genuinely surprised by some of the comments shared. I was blind to what was actually going on behind the scenes on campus. I felt insecure in the environment, even though I wasn’t personally aected. Then I thought about what had happened with my sister. It had been so close to me but so unrecognized by me personally. The number of reports was unbelievable. I really did not know what to think as I watched the news of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Rayshard Brooks—Black men whose final moments we all witnessed, and who weren’t given the benefit of the doubt. In two of the cases, the death was caused by law enforcement. I have mixed emotions about the relationship between African-Americans and law enforcement because my father is a career law enforcement ocer. I know for sure that my dad as a law enforcement ocer can be trusted, and yet I see what everyone else saw in the George Floyd case. It’s clear that law enforcement does include humans who can’t be trusted 100 percent of the time. As a result, there has been a proliferation of protests ranging from peaceful, powerful, and productive to chaotic and destructive that negatively impact the communities that can least aord such destruction. I attended two demonstrations in Atlanta. It was extremely powerful to see so many individuals gathered with one goal in mind. They were there to shed light on police brutality and injustice. I stood there hoping that the peaceful protests would bring attention and spark change in the community for those who so desperately needed it. That will require a conscious eort from all members of the community. This should become a focus of our school community. Woodward has some work to do in light of the release of the Black at Woodward posts. However, I feel if the proper steps are taken toward starting a dialogue and educating the student body on these topics, then we can use these posts as a lesson and hopefully bounce back as a more welcoming, cohesive community. Woodward Academy does a great job of supporting diversity in a very inclusive way. I hope it will build on that to help its students go out into the world respecting and honoring dierences.

35A Special PublicationFREQUENTLY IN CONVERSATIONS WITH OTHER PARENTS AND SOME FACULTY, A DISCUSSION ERUPTS AROUND “THE CHANGES” THAT HAVE OCCURRED AT WA AND HOW PERHAPS CERTAIN SOLUTIONS COULD SLOW OR REVERSE THEM. YOU REALIZE THEY ARE TALKING ABOUT THE INFLUX OF MINORITIES (MOSTLY BLACK STUDENTS). ... THEY WANT UPPER-MIDDLE INCOME “GOOD BLACKS,” NOT THE LOWER-MIDDLE INCOME “BAD BLACKS.” IT PERMEATES INTO HOW THE STUDENTS INTERACT AND TALK ABOUT EACH OTHER.ANONYMOUS PARENT

36 BLACK AT WOODWARDI did a social experiment with one of my white friends and we both did one thing out of dress code the same day. The teacher let her slide but gave me, the Black student, a uniform violation. Then my friend made hers more noticeable and still no violation.ANONYMOUS STUDENT

37A Special Publication

38WHEN MANY VOICES BECOME ONEBLACK AT WOODWARDNATHANIEL JOHNSON ’12

39A Special PublicationI have always had great pride about growing up in Atlanta and attending Woodward. I’ve cherished the experiences and relationships I gained growing up in the city that, as Mayor Ivan Allen said in the 1960s, is “too busy to hate.” This summer, after reading the stories on the Black at Woodward Instagram page, I reassessed my experience as a Black man attending a predominantly wealthy, white institution. It was heartbreaking to see that current Black and brown students are still dealing with the microaggressions and blatant racism that we experienced. Yet, it’s also empowering to see these young adults turning their voices and stories into a movement. Their movement inspired people to make a dierence, and it is a testament to the character and drive of today’s Black and brown Woodward students. They aren’t settling for the status quo. I was amazed when I heard about the Black Student Union at Woodward and was envious, I have to admit. Our classes hadn’t tried to start one before. Today’s students are dierent in the sense that they know they have power when they come together. During this period of upheaval, I started talking with Kendall Roney ’12 and Morgan McKinnon ’12 about creating a Black Alumni Association. We felt that this was the first step necessary for us to be an active part of the change we want to see. I believe it is our responsibility as Black alumni to support the students and recent graduates.We asked ourselves what it would have been like if we had a Black alumnus as a mentor. And what about a database of Black professionals who attended Woodward? How much of a dierence would it have made during our time at the Academy? With a Black alumni network, opportunities for Black students and recent graduates for internships, mentoring, resources, career shadowing, and networking would build lifelong relationships and success. As we have seen from the current students, collectiveness can spark immediate change. If Woodward’s Black community can come together, that is an incredible, vastly talented group that can make a massive impact at Woodward, across Atlanta, and in the world at large.This summer, I learned a great deal about how much dierence we can make in the world when we collectively use our voice and have an actionable plan. Witnessing the Black students and recent alums’ passion while leading this movement has made me even more proud and thankful for attending Woodward Academy. The Black Alumni AssociationMissionThe Woodward Academy Black Alumni Association highlights excellence among its members and creates a community that works together to empower students and alumni, cultivate lasting connections, strengthen the Woodward community, and provide the space for scholars and professionals to connect and deepen relationships beyond the Academy. VisionAs the Woodward Academy Black Alumni Association, we strive to provide networking opportunities, social events, and philanthropic support to the school. We connect alumni to current students with shared experiences in order to provide mentorship that will equip them with the necessary skills to navigate through their time at the Academy and beyond graduation. Together we will strengthen the Woodward community through advocacy and mobilization that will foster greater educational opportunities and resources for Black students, school organizations, and faculty. For more information, email blackalumni@woodward.edu.

BLACK AT WOODWARD40In order for you to appreciate my Woodward story, I need to take you back in time for just a moment. When I was growing up, I had no clue we were poor. My family was rich in love and support and kindness and caring. And the “village” that raised me left not a single doubt in my mind that I was loved. But the experience that really set the course of my young life happened when I was in fifth grade. It was the first year of desegregation, and I had to move from my all-Black school—where I excelled even with hand-me-down books and second-rate facilities—to an all-white school. Before I moved to the new school, my teacher, Mrs. Bryant, pulled me to the side and said, “Now you will be going to school with white kids, and I want you to understand something very clearly. No matter what anybody tries to make you believe, never forget you are just as smart as any of them. There is nothing you can’t achieve with hard work and applying yourself.” I’ve carried her words with me ever since. I went on to graduate as valedictorian from my high school and from there I got my BA and MBA. I began my professional career in 1976, and I retired as executive vice president, finance at Coca-Cola Enterprises in 2009. During the entirety of my 30-plus year career, I never once had a boss who looked like me in race or in gender. And so, as you might surmise, I have lived a little bit of this thing called diversity.‘The Responsibility to Make it Right’BY VICKI PALMER

41A Special Publication My daughter, Alex Roman ’07, started at Woodward in fifth grade. I chose Woodward because of its reputation for educating the whole child and for diversity. So, imagine my surprise when we showed up for the first gathering of new parents to meet the faculty and administration, and there were exactly two Black people. One was the chaplain and the other was the Lower School counselor. I was literally speechless. When Alex was in sixth grade, the president of Woodward approached me about joining the Governing Board. I told him I would consider it, but he needed to understand I would be bringing a platform with me. I went on to explain that my daughter could not attend a school where she wouldn’t have teachers who looked like her. Thinking back to my own fifth grade experience, I fully understood the value of Black teachers in the development of my Black child. I deliberately surrounded her with role models who looked like she did. Her pediatrician was Black, her dentist was Black, her pastor was Black, all because I wanted my child to understand clearly that there was nothing in this world she could not achieve as a Black woman. The president said he understood and that they were committed to change. And things did change, for a while. I’m proud to say that Alex herself played a role in creating change while she was a student. When she was in ninth grade, she came home ranting and raving about the fact that Woodward did not do anything to honor Black History Month. I let her finish and then said, “There are two kinds of people in this world, those who complain and those who choose to do something about it. You need to decide which type you want to be.” We never discussed it again until I learned she had gone to the administration with a plan for a Black History moment daily for the month of February with students of various ethnicities participating. It was very well received. Later, she wanted to start a Black student group but was told that groups for individual ethnicities were not allowed. So she started the multicultural group, Five Points, in the Upper School, for which she won the Princeton Prize in Race Relations. And yet, despite all the work of those years, I find myself more than 20 years later hearing the very same concerns. That Woodward, still, is not doing enough to create an equitable environment.And so, when I was first asked to chair the Anti-Racism Task Force, I had real reservations. I had already paid so many dues, fought so many fights, and tried hard to make a dierence during my career. When I was treasurer at Coca-Cola Enterprises, we were one of the first corporations to hire a Black money manager for our pension program—actually, we didn’t just hire one, we hired three. On Wall Street, we completed the first ever bond deal in this country that was led by a Black investment firm, a $300 million transaction. I used my seat at the table to make a dierence for our employees and to make sure we had diverse representation at all levels of the company. I know what racism feels like, and I understand the responsibility to make it right. I truly felt the pain expressed on the Black at Woodward Instagram account, and I knew it was going to take a lot of time Woodward Student Body DemographicsWhite 42.9%Black 31.6%Asian/Pacific 11.7%Hispanic 2.2%Native American 0.2%Multiracial 7.7%Not Provided 3.6%

BLACK AT WOODWARD42and hard, tough work to make meaningful change. I also was very clear that before I could make a decision, I had to have two serious conversations. One with President Gulley and another with Bobby Bowers ’74, our Governing Board chair. I asked them both if they were truly 100 percent committed to making the necessary changes, wherever this work took us. After those conversations, I was convinced of their personal commitment and their genuine level of shock and dismay with the hundreds of stories from alumni, and even more sadly, from current students. Many have asked, how could the Academy’s leaders not have known that such racist behavior still took place? Of course, leaders knew of what we thought were isolated issues over the years, but just like every major corporation and educational institution in this country, they had never heard so many voices speaking so loudly and clearly, at the same time—many for the very first time. The scope of the problem was never so clearly defined, and so unavoidable. And so, I agreed to serve as chair. For the past four months, Woodward’s Anti-Racism Task Force has been hard at work tackling perhaps one of the toughest issues in America: the pandemic of racism. The term “Anti-Racism” denotes the act of change. I am more than hopeful for our Academy because we have the kind of courageous leadership that is willing to make such needed changes in order to end systemic racism wherever it may exist—overt or unintentional. I am proud to be part of the solution at Woodward Academy. It is my hope and my prayer that all of you will join us to do your part to make Woodward an example for independent schools around the country to emulate. With your help, we can put an end to any injustices for every member of the Woodward community. Vicki Palmer is a retired executive vice president at Coca-Cola and president of The Palmer Group, a consulting firm. She is the chair of Woodward’s Anti-Racism Task Force and a member of the Woodward Governing Board.Diversity, Equity & InclusionWoodward has engaged in ongoing work in Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, led for the past several years by Marcia Prewitt Spiller, the senior vice president for academic and student life. While Woodward is the most diverse private school in Atlanta, more work is needed to create a school environment where discrimination or hatred of any kind is not tolerated.It is the school’s sincere belief that we can only be eective when our entire community—parents, students, alumni, faculty, sta, and administration—works together to put an end to such injustices. Our commitment to the Woodward community moving forward is to provide ongoing progress updates and transparency about our approach to the important work ahead. The Anti-Racism Task Force will post updates about its work in the Woodward magazine and on the DEI page on the Woodward website at woodward.edu/dei.The page includes information on hate speech, academic leveling, diversity training, curriculum review, and financial support.

43A Special Publication“The Great Escape”GABBY LARMOND ’21

Discipline students for racist remarks and comments. We also need mandatory assemblies so that people of color can share their experiences. We get one every year about drugs and alcohol and dating, but why not about racism?KENNEDY ROGERS ’2344

45The racism that I have seen at Woodward has spanned three decades. I have experienced everything from overt racism to implicit bias to countless microaggressions. I have had to guide my own children during their time at Woodward through the same types of experiences of racist comments from peers and their families, ignorant, ill-informed comments from faculty, disparities of discipline and responses. ANONYMOUS ALUMNUS AND PARENT

46‘What is at Stake is Our Humanity’F. STUART GULLEY

47Much of what you’ve just read in this publication—and many more accounts of racist incidents at Woodward—came to light over a period of a few months this spring and summer. I and the other leaders of the Academy watched as these stories piled up, an ever growing list. And as we read, we grieved.The stories are horrifying. They would have been painful to read, even if I’d had no personal connection to them. But it was all the worse because these stories happened here. Many of them happened under my watch, these incidents of microaggressions, bullying, and outright racism.I knew, of course, of isolated instances. It is part of being a large community, comprising thousands of individuals, that there will be problems. The sheer volume posted online and shared directly with us, though, put the lie to this conception of scattered, unrelated incidents. We have prided ourselves on being a place that practices a deep respect for dierence. What these accounts made me understand is that our culture is neither as deep nor as respectful as I thought. It is doubly painful for our community that people have felt unheard or ignored when they have reported racist behavior. We know that we haven’t done enough to create real, consistent accountability. And, thus, we have been one more organization that created a system that holds back people of color.