Return to flip book view

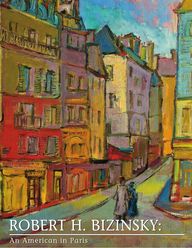

ROBERT H. BIZINSKY:An American in ParisROBERT H. BIZINSKY:An American in Paris

PRESENTED BY:ROBERT H. BIZINSKY:An American in Paris330 Pequot Avenue | Southport, CT 06890 | P: (203) 292-6124 | southportgalleries.comSOUTHPORT GALLERIESNovember 5 — December 312011

2You don’t have to be a Hollywood producer, Broadway lyricist, orbest-selling novelist to capture an irresistible story. Add into the mix thepicaresque adventures of a dashingly handsome young man. He’sarmed with a box of paints ready to brush onto raw canvas fantasticalimages in a symphony of colors. Picking up those tools, the artist went forth launching a promisingcareer. Six decades later, we now have the pleasure of viewing the results of this artist’s Paris sojourn. This pictorial legacy is not so muchabout our intuitive notions about the glories of Paris from yesteryear –but speak to our most primal understanding of what constitutes genuinely worthy art today. Like a dream sequence in a Chagall painting, he has painted himself into this story. Enhanced by our protagonist’s joie de vivre, theseductive pleasures of artistic expression are passionately embodied.The art and life of Robert H. (Hyman) Bizinsky [1915-1982] is simply tooexceptional to remain undisclosed.Bizinsky’s biography unfolds as an authentic American enrapturedwith Paris in those halcyon days in the late 1940s. Vividly invokingpainterly lessons of modernity, he surveyed its cafes, boulevards, oddlyarranged book shops and antique markets. Following in the footstepsof earlier American painters –Patrick Henry Bruce, Marsden Hartley, orJohn Marin – his artistic pilgrimage to ‘La Ville-Lumiere’ defined thezenith of his career. Like a siren’s call to the City of Light, Bizinsky wasmagnetically pulled into the radiant beam of the Eiffel Tower’s searchfor up and coming young artists.Seeking his own artistic voice, his paintings reverberated with thebreakthroughs of post-Impressionism. At the very moment when abstraction was all the rage back in the States, he animated his palettewith a ‘couleur-lumiere’ enriching his depictions of urban Paris andthe French countryside. ‘Biz’ – as he was affectionately known – was well schooled by his Parisian mentors. It took a young American to catchthe tail end of the School of Paris branding it with his own carefree, ‘Yankee doodle’ insouciance. Let’s try to forget preconceptions of touristy post-cards showing a faux Paris in contemporary cartoons or travel posters. Here we embraceParis after the occupation but before being overrun by mass tourism with the advent of the jet-age. A wistful authenticity is palpably sensed in the catalogue for an “Exhibition of American Veterans in Paris.” An ambitious event staged in January, 1948 under the auspices of the United States Embassy, it filled the walls at the Pershing Hall on the Rue Pierre-Charron. This elegant early 19th century palais, a prime example of the Empire Style,was General John Pershing’s general headquarters in WWI. The exhibition’s broadside published a statement of the organizing committee, with Biz listed as one of its authors: “This is the first show of importance in Paris exhibiting the work of young Americans who at the Wars’ end laid downtheir arms to continue or begin their lives as painters or sculptors. They have come to Paris from all parts of America insearch of its great artistic traditions – to stand before its magnificent art treasures – the Louvre, the Petit-Palais, the Impressionists, the Cathedrals, the Bridges, the Gardens and its hundreds of other wonderful monuments – Paris, the mostbeautiful city in the world despite its War years.” These canvases are distinctively his inheritance of the visual rhythms by Cezanne , Matisse, and Derain – and laterby Dufy and Utrillo. With agitated swatches of bold colors and unrestrained outbursts of undulating lines, Biz paintedthe Place Pigalle, the Lapin Agile, the Moulin Rogue and the bookstalls along the Seine.Unerring, with a discerning eye and responsive brush, he conducts an American symphony orchestrated in the moodof a resurgent Paris in its post-WWII years. These famed locales were glimpsed with renewed vigor and incorporated distinctively as elements of his repertoire. In their totality, Biz presented a panorama of a storybook Paris which exists inour mind’s-eye with lingering nostalgia of a world now vanished.ROBERT H. BIZINSKY:AN AMERICAN IN PARISPhilip Eliasoph

3Surprisingly, this artistic treasure has remained an unknown puzzle. Most of what we are presenting in this exhibition has not been seen in over 60 years since the moment when paint was still dripping off the artist’s palette.Through a ‘wrinkle in time’ we are now ready to reassess the unsung achievements of an American original. Collectors,curators, and connoisseurs appreciate that sometimes art history is not just about the celebrated, big-name artists of eachera. Drilling deeper into the mine shaft, on rare occasions we just might find a hidden vein of gold.From 1936-1942 Biz attended art classes at Atlanta’s High Art Museum school. To support his art training, he rosequickly as the resident artist at ‘The Atlanta Constitution’. These editorial page sketches gave him a firm idea of the ‘quicksketch’ capturing the expressive mood of subject, time and place. As the war arrived, he dovetailed his professional skills with the Army’s plans for his service. Before enlisting in thesummer of ‘42 he traveled to Provincetown to attend Hans Hofmann’s now legendary painting class. Like millions of ambitious young men of “The Greatest Generation,” he went off to war uncertain of how its outcome who eventuallyshape his life. At first stationed in Ireland, Scotland and England, he arrived in North Africa as an Army art correspondent with the1st Armored Division. In February, 1943 his unit was thrown into the Battle of the Kasserine Pass in the Tunisian desert.As an eyewitness to this bloody engagement against Gen. Erwin Rommel’s battle-tested Afrika Corps , he saw the deathof over 1,000 young American GIs. Those horrific days thrust young Biz into adulthood as violent days of reckoning. Outof that harrowing dance with death – he was determined to celebrate life through art. In a memoir, Biz wrote: “I have been in the presence of death on innumerable occasions…I have felt the hot and coldbreath of my buddies as life ebbed out of their gaping wounds. At every brief minute or ‘break’ I devoted my leisure tosketching in pencil, pen, and ink, or in watercolors, my surroundings.”On the North African battlefield, he produced over 580 drawings, sketches, and watercolors documenting that bloodyrout which are today in the U.S. Army Historical Center’s collection in Washington, D.C. Still in active service, Biz received a letter of commendation dated May 9, 1944 from the High Art Museum’s director which noted:“You may be sure that we will show your work in the continual monthly shows as a reminder to us and your manyfriends how much a soldier cares about art on the home front. Your attitude is not, certainly, neutral or Pearl Harbor-ishabout what you are willing to fight for and we all think your action in this case speaks louder on the subject of what isimportant than any number of words we could put down.” Recognizing his innate talents, his Army superiors assigned him to the military hospital in Casablanca where he became a loved instructor rehabilitating wounded American GIs. He wrote after returning to the States: “the ten monthsI put in doing this work helped convince me of the great role a good artist and art organizer could play in sponsoring inter-relationships between races, differing in their ideals, intellectual concepts, and general modes of living.”He was selected to an elite showing of combat artists at the National Gallery of Art’s summer, 1945 exhibit of “Soldier Art.”Drafting a short autobiographical summary as he returned to civilian life, Biz wrote: “I am 29 in excellent health, with a great capacity for work. With a minimum of bias I consider myself sincere, prolific of output, essentially most promising, and greatly in love with my work.” After the war he returned to Atlanta to visit family where he was greeted as a hero in the local press: “Biz served withthe Army combat engineers until his discharge [as corporal] in 1945. Now he lives the kind of life that many envy, butfew would try. Living and working wherever he feels inclined to go. He enjoys the true realism, the true sophistication ofthe French. ‘Europeans accept everything,’ he says, ‘their sophistication is inborn, not a veneer or an artificiality as withmany Americans. The best dressed woman in Paris may conceivably walk down the street with a ragged man.’” Biz used his GI Bill to enroll in classes at New York’s Art Students League, an artistic hothouse with notable paintersof his generation including Milton Avery, Will Barnet, Paul Cadmus, Adolph Gottlieb, and Jackson Pollock. Mentor HansHofmann considered Biz a star pupil at his Provincetownworkshop and in 1946 recommended continuing histraining in Paris.This was just at the time and place when Manhattan ‘stole the show’ from Paris as the capital ofavant-gardism. At mid-century, the macho- muscularityof New York abstraction won the art war. Ah, but Paris retained an aroma of sweetly fragrant memories. New York was more cutting-edge angst. Paris retained itslingering ‘nose’ like a round goblet of properly aged Bordeaux. By 1948 he was enrolled at the Academie del laGrande Chaumiere, and nominated for the Prix de la Critique. This haven for aspiring modernists – withnoteworthy alumni: Alexander Calder, Alberto Giacometti, Isamu Noguchi, and Amedeo Modigliani –only offered the bare essentials of “a nude model andheat” in the winter. The ‘Large Thatched Roof Cottage’school was a beehive of independent artistic practice.

4Biz had no inclination for the conservative theories or rigid rendering practices of the Ecole des Beaux Arts. “At theAcademy of the Grande Chaumiere they told me that Bizinsky was the best American student they ever had,” wrote Atlanta Constitution Editor Ralph McGill. In its lead editorial on Dec. 19, 1949, we learn that Biz didn’t “go Paris.” Thiswas no holiday: “he worked - I’m proud of him.”The seductive force of Paris --its art academies, cafes, and artistic milieu - pulled Biz in the opposite direction. He wasnot among the leading edge of Americans entering into Greenwich Village action painting . Biz took emotional refuge inthe advances of early modernism: inspired by Cezanne, and the direct pupils who were the Fauvists, late Cubists andloosely allied ‘School of Paris’ painters. He easily fell into the polyglot realm of these ‘les maudits’ – (the cursed) who employed expressive distortions and highly abstracted forms in their churning, swirling images of people, places, and landscapes. Most notably, Bizinsky studied with the eminent painter Achille Emile Othon Friesz (1879-1949). A disciple ofCezanne, the younger Friesz was among the original circle – including Matisse, Dufy, Vallotton, and von Dongen– to showat the February, 1904 exhibition at the Salon des Independants. That historic event of rebellious painters displayed canvases in a riot of color. As anti-academicians overthrowing the pompousness of antiseptic realism, they invented Fauvism. From this legacy of Cezanne and then Friesz, the Fauves – “wild beasts” – employed distorted perspectives, dismembered forms, and outrageously arbitrary colors (orange clouds, lavender hair, purple trees, pink bridges, blue bananas) to upset the expectations of the viewer. To honor this aging lion of early modernism, young Bizinsky felt he wasan heir to the mantle of both Cezanne and his pupil Friesz. Carrying forward their torches, Bizinsky’s paintings are anhomage to these giants of French modernism. The post-war years seem to replicate or overlap the experience of other American artists and writers. His ramblingexperiences -- an American ex-patriot, WWII vet living la vie boheme on the Rive Gauche -- rings pitch perfect with another classic. Syncopated to Gershwin’s melodies in 1951, Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron romped across MGM’s back lotfacsimile of the City of Light in ‘An American in Paris.’ As a broad-shouldered, attractive American bachelor with a fewgreenbacks in his wallet – entertaining the local ladies, one could only ask: “Who could ask for anything more?” An unquestionable talent, critical fame, and a flash of international notoriety notches up Bizinsky’s narrative. It wasin the August 22, 1949 edition of LIFE magazine that Bizinsky came to the world’s attention. It was his destiny that anarticle would include him in “The New Expatriates”. Biz’s appears – like a leading man from central casting - in a wonderful street scene entertaining four Parisian street waifs with a freshly painted oil work on his easel. This photo documents a transcendent truth: Biz was there!He told LIFE’s correspondent: “In the States an artist in the family is a disaster. His folks think he is wasting time andhe isn’t too sure that they aren’t right. Here we are all trying, and the very atmosphere of the place helps…You get respectful attention in the States only after you area success – not before, when you need it.”The background settings for this epic lifetime changed in period, style, and localizedscenery. His sparkling, colorful palette and eye forlocal detail captured biographical events with a robust vitality. From the blinding sandstorms of the Tunisian desert in tank warfare, to the artists’ garrets and studios nestled into Montmartre and Montparnasse, or his later years insouthern Californian light, Biz sketched and paintedhis autobiography with a bold vibrancy.From war’s traumatic experience, he toowas in that generation of non-conformists, rebels,‘beatniks’, and philosopher kings in their own right.Rejecting the ‘get a profession’ expectations of hisOrthodox family, he set out into the world as arugged individualist. Like Saul Bellow, BernardMalamud, or Philip Roth, he wrestled with his Jewish identity within the context of a conflicting,existentialist modernity. Certainly as a Jewish GI,the defeat of pagan Nazism was deeply personaland essential.And yet, his newer identity sought universal recognition in the greater art world beyond race, religion, or caste. Assuch, Biz’s consciousness sought engagement with a wider set of challenges knowing his art plunged the deepest depthsof his soul. These conflicts of modernity were equally experienced in the ambivalence towards the Second Commandment’s iconophobia. Other Jewish bohemians in Paris: Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani, Jules Pascin, ChaimSoutine, and Osip Zadkine, had no option but to invent a new covenant for the visual arts. Similar to Jack Levine, Ben Shahn or even Alex Katz, Biz never dismissed elements of the natural world in his

5pictorial rhetoric. He remained true to his vision as a mystical visionary beforean invisible but sensorial notion of the Almighty. One could even view his Jewishness was most applicable in depicting nature as something ineffablypowerful but outside of physical description. Surveying his golden moment - -Paris in the late 40s – Biz was truly an ascending painter in that era. Reviews from credible critics and objective observers in the Parisian and international press uniformly praisedthis up and coming American. “The G.I. Bill produced at least two artists of extraordinary talent who won later fame,” declared William E. Share, Attacheat the American Embassy in Paris. “The first, Norman Mailer…The second isRobert Bizinsky whose modern landscapes are now commanding top prices inParis salons.” Enabled with 20/20 hindsight we can confidently determine his enduring artistic integrity. One colleague who recognized his enormous abilitywas the notable Parisian critic and poet Philippe Soupault. Introducing his exhibition at Le Galerie Sainte-Placide [Jan 15-30, 1949]Soupault, considered the first Surrealist poet, wrote admiringly:“Bizinsky came from the United States like a boomerang (returning afterthe war’s end) and has set forth on the discovery of a new world. He does not fearpitfalls. The capes and peninsulas bear the names of celebrated men, as themountains and lakes are christened to honor memories. I am thinking of MountPicasso, Lake Braque, or Cape Matisse…We will admire the courage, so rare, of a painter who is willing to listen only to himself.”By the early 1950s he settled in Los Angeles and became a respected senior member of a growing art community. Hewas afforded continuing recognition indicated by the renowned playwright and essayist Christopher Isherwood, whosememorable “Berlin Stories” about Sally Bowles formed the libretto of “Cabaret.” The artist and author became friends inthe nouveau culture of southern California.Isherwood proclaimed: “Bizinsky’s work has a quality which stimulates greatly…He can make you share his appetitefor a scene so that you wish you could eat it. I suppose Bizinsky gets this affect by his highly evocative use of color. Butbehind this brightness, there is something more mysterious and sophisticated.”Fortuitously, we are among the first to hear about -- or to see – compelling evidence of this productive artistic career.It was art expert Gene Shannon and his wife Mary Anne who believed “right down to their toes” in the artistic quality ofthese canvases. The Shannons flew out to Los Angeles in 1989, seven years after the artist’s passing, with a keen interestand eagle eye for artistic quality. Shannon negotiated with Bizinsky’s widow, Eleanor Anita Guggenheim, to acquire the remaining assets of the Estate.But beyond an incredible cache of prime ‘mid-century’ canvases capturing the Paris of a bygone era, he made a solemnpledge to Mrs. Bizinsky to shepherd the future legacy of these important artworks. Each painting has been authenticated with the official ‘stamp’ of the Bizinsky Estate executed under his widow’s supervision. “Mary Anne and I felt obliged to live up to Eleanor’s wishes as she was fully committed to her late husband’slasting artistic bequests.” As a testimonial, this exhibit fulfills that promise.Now restored into a new light and resurrected from the shadows of time, this exhibition presents a major artistic re-discovery of an artist who lived out his dreams. That great icon of American art, Edward Hopper, once noted his skepticism about the ongoing recognition for aging or forgotten artists. Hopper, a curmudgeon of sorts, said it well:“Ninety percent of them are forgotten ten minutes after they’re dead.” With gratitude to the Shannons’ intuitive instincts, we are not going to forget Biz. With this exhibition, we are escorting him back from the indignities of artistic extinction. Inevitably, this publication ensures that Bizinsky won’t beerased from the history of 20 th century art. That unique experience of the quintessential “American in Paris” is our privilege to now cherish. Any viewer with asensitive eye and warm heart will undoubtedly rejoin Biz along his marvelous journey painted over six decades ago. Justat that magical moment when Julia Child began mastering the art of French culinary delights in 1949, Biz was also cooking up his ‘grand bouffe’ on canvas. Infused with ingredients of throbbing, tremulous outlines and intense coloristicliberties, his images arouse ambrosial delights of places seen and imagined. Perhaps, it is within the aroma of Paris ofthat era in these paintings which most poignantly impacts our senses.Allowing us to wander aimlessly around the very idea of Paris – he created this collage of cozy cafés, juxtaposedstreet corners, elegant bridges and grand monuments -- leaving us an enduring legacy. Bizinsky’s art – now and then – remains unquestionably and deliriously an enviable ensemble of paintings. As this re-discovery proves, Robert H. Bizinsky’s art is inescapably ‘tres magnifique!’ Philip Eliasoph, Ph.D. is Professor of Art History at Fairfield University. His lifelong pursuit is the rediscovery and reassessment of forgottenAmerican artists of the 20th century who once held positions of critical significance. Advocating their meritorious – but overshadowed-- achievements, Dr. Eliasoph has published groundbreaking monographs on Paul Cadmus, Robert Vickrey, and Colleen Browning. Heteaches American Painting, Florentine Renaissance Culture, Art & Nazism, Museum Studies, and Jewish Art: From Moses to Modigliani.

1. Woman and Child, Tuileries Gardensoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

7 “The G.I. Bill of Rights produced at least two artistsof extraordinary talent who later found fame. The first, Norman Mailer, author of the best-sellingnovel, The Naked and the Dead who studied here in1947. The second is Robert Bizinsky whose modernlandscapes are now commanding top prices inParis Salons”— United Press Stars and Stripes quoting William E. Share, Attache, American Embassy.

8

2. Strolling Down a Parisian Streetoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

3. Scaré-Coeur from the rue de Montmarteoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

11

12THE LYRICAL POST-IMPRESSIONISM OF ROBERT BIZINSKYby Anne AyresThe joyously colorful paintings of Robert Bizinsky are witness to a lifetime contemplation of nature and the external motif. His landscapes and cityscapes reveal an artist not only gifted in hiscraft but acutely attuned to the harmony of the world. Whether working in the style of postwar Schoolof Paris naturalism or in the California landscape tradition, his best paintings combine commitmentto the objective impression with a sensitive interpretation expressed coloristically.In this synthesis Robert Bizinsky considered himself an esthetic descendant of Paul Cezanne andhis dictum concerning the realization of nature through the forms of sphere, cone and cylinder. But like Cezanne himself, Bizinsky took nature for a teacher and never abandoned the recognizable image for geometric abstraction. Praised by French critics for his independent path, he avoided the non-representational, freely gestural Art informel that paralleled in France the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in New York. Rather Bizinsky’s vision remained post-impres-sionist. It was explored initially in a youthful body of American Scene paintings of his native Georgia; later was developed in sketches and watercolors of soldiering in North Africa during World War II.Bizinsky’s post-impressionist bent was refined and strengthened in Paris by an admiration for the coloristic pictorial harmonies of Henri Matisse and French fauvism - particularly as revisited in apost-1945 independent French expressionism. Thus Bizinsky became the protégé of Emile-Othon Friesz,a pioneer fauvist and cultivated School of Paris painter who taught at the Academie de la GrandeChaumiere where Bizinsky studied.There are indeed felicitous reminiscences not only of Friesz but also of other originators of fauvism(Raoul Dufy, for instance and Albert Marquet) in the lighthearted charm of Bizinsky’s Paris cityscapes.The American artist however,was more concerned withpictorial depth, solidity ofconstruction and clarity ofoutline. Bizinsky’s Paris legacy was to be nourished by the bright color and often brutallight of Southern Californiawhere he settled in the early1950’s. The sun drenchedpaintings of this period, freerof brushwork and more relaxed in construction, showan intensification of the tart accents of the Paris work aswell as sharper color contrasts. Pure landscapes capture the foothills, flora and verdure of the LosAngeles environs, but more often man is included, shown neither dominating nor dominated by nature but sharing in a rhythmically expressed harmony. The paintings are those of a man joyously at ease with being-in-the-world, one who felt deeply the significance f an artistic vocation:…individual harmony…that’s a man’s reason for existing. The reason that man paints is to

4. Musee Du Louvre and the Seine, Parisoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

5. Outdoor Cafeoil on canvas, 14 x 18.

inventory this harmony. If a painter is capable of turningout a painting every day, he more or less has a diary of whathis existence has meant to him, of how he is related to theuniverse.1This response to life and the work it informs is rooted inBizinsky’s formative experiences in his native Georgia andin the maturing influences of his Paris studies and worldtravels. As a painter and teacher living in Brentwood, LosAngeles, Bizinsky shared his thoughts on life and art in ananecdotal column in the local newspaper call “Form andColor.” Certainly Bizinsky’s world had always been that ofform and color. His earliest memories were of colors –“veryvivid yellows and reds and greens, dark bodies with purplecasts, dark bodies against white cotton, golden stalks of cornand the red earth.” 2Those were the colors of the AmericanSouth where Hyman Robert Bizinsky was born on June 17,1915 into a Jewish-Russian family that had immigrated toGeorgia in 1905 and settled permanently in Atlanta following World War I. The young Bizinsky led a ruggedand idyllic American boyhood roaming the “Cherokeecountry” and exploring the Okefenokee swamp.The security of Bizinsky’s childhood no doubt affectedthe subject matter and tone of his later painting, but the initial pull toward art must have seemed challenging. The community was provincial; and a patriarchal and Orthodox father, ambitious for a medical career for his son, did not encourage artistic yearnings. But nature showed itself to Bizinsky as a complex phenomenon of form and color,and it was then that the adventurous youth became committed painter:…the three dimensional world grew less interesting that the two dimensional one – and the problems of the two dimensional world must be faced on canvas.1Bizinsky’s youth was not, however, without artistic precedents. He was inspired by the colorpatches of Cézanne and the energized line brilliant color of Van Gogh, books having been suppliedby an understanding aunt. He discovered for himself the perhaps more accessible narrative excitement and dash of the Western “cowboy” painter, Frederick Remington. By the mid-1930’s, Bizinsky had taken for his heroes such regionalist as Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry. When hefinally approached Ralph McGill, the crusading editor of the Atlanta Constitution, Bizinsky was calling his work “regionalism in painting” 1– and himself a young man who needed a job.It was the height of the Depression, but McGill was impressed by the young artist’s willingness towork for the price of paint and canvas. Soon Bizinsky was working at night for the Constitution; and,as “Biz”, he contributed cartoons of political, sports, and theatrical celebrities and originated “Georgia Oddities” for the Sunday magazinesection. During the day he attended classes at the HighMuseum of Art. McGill, first a beloved mentor and then an appreciative collector of Bizinsky’s paintings, remained a lifelong friend.In February of 1942, Bizinsky joined the army. He grasped at the army not only as a patriotic service but also as a “great Opportunity” 1– a way out of the situation in Atlanta that could not channel his professional ambitions. Bizinsky’s background indicated the camouflage corps, but heended up instead as an infantryman in the First Armored Division of the Combat Engineers.The Combat Engineers were shipped off to the harsh North African campaign of 1942-42; 15“I feel, I have discoveredhim in France,”announcedFriesz–“There is agreat latitude ofstrength and sensitivity in thepainting of Bizinsky.”

Bizinsky’s company was in the thick of the actionbetween the Allies and the German Africa Corps,including the bloody engagement at Kasserine Pass.But by mid-year Bizinsky’s teaching skills sent himto the Atlantic Base Section Headquarters inCasablanca where he set up art classes for woundedsoldiers. All the while his artist’s eye responded tothe clear light and vivid colors of Tunisia and Morocco. He felt kinship with earlier artists abroadin North Africa - Delacroix, Matisse, Klee- and hispencils and brushes were always busy.Bizinsky rotated home to the States in April1944 and the remaining months of his service werespent teaching in the Occupational Therapy Department of Batty Hospital in Rome, Georgia. Hewas given an exhibition at the prestigious High Museum of Art but Paris, still considered the traditional center of the art world, beckoned. As aninterim step, Bizinsky attended on the G.I. Bill ofRights the Art Students League in New York. Aftera high recommendation from the director of theASL to the École Nationale Superieure des Beaux-Arts, Bizinsky departed for Paris on November 10,1946. The happy legend of “Vie de Bohéme” was of an earlier Paris rather than that of the gray postwar city. But if the climate was literally cold and money was always short, the artistic ambience remained warming. Inspired bya life of hard work in the ateliers and good talk in the cafes, Bizinsky fell in love with a Paris where“all the world paints” and “the role of the artist is not separated from the life of the city.”1There wastime for travel too, and Bizinsky profited from sketching trips to Brittany and the South of France.Spain and Italy especially were fruitful experiences.In Paris, Bizinsky participated frequently in group exhibitions and helped to organize many. Numerous currents from the past flowed into the French academies after the war. Most apparent inthe group shows were a late synthetic Cubism verging on the non-objective; romantic nudes in themanner of Modigliani; and a surrealist figuration derived from Picasso. Bizinsky however had different mentors: the old master fauvist Emile-Othon Friesz, of course, but also a later generationartist exemplified by Yves Brayer, who painted vigorous and colorful expressionist landscapes of Southern France. Bizinsky worked in the atelier of Yves Brayer for three years and was considered byhim to be “incontestably the most gifted of the American veterans.”It was Bizinsky’s passion for following an independent direction that led him to be singled out as an American star in Paris destined for a career of excellence – and, indeed, in 1948 hewas sponsored by Friesz for the prestigious Prix de la Critique. He was praised by critics for his “beautiful qualities, fresh touch and solid way of painting” and embraced as “an ardent colorist andtender observer of our streets and way of life.” The internationally renowned sculptor Ossip Zadkinetold Life magazine that,. . . you can put this down and sign it Zadkine: There are boys her now the States are going to hearof – Paul England and Kenneth Noland and Robert Bizinsky.2Further, it cannot be overemphasized that in the esthetic chauvinism of postwar France it was an16

6. Fountain at St. Paul de Vence oil on canvas, 21 x 32.

7. Across from a Cafe, Parisoil on canvas, 21 x 25.

unsual accolade to be one of the few Americans given a one-man exhibition in a noted Paris gallery.Consistent with the high esteem accorded Bizinsky, the Gallery Castelucho introduced his work withan appreciation by the celebrated Surrealist writer, Philippe Soupault. Perhaps in a tip of the hat toAmerican’s vaunted individuality and rawness, Soupault stressed the “unsuspectingly rare” quality ofspontaneous openness in Bizinsky’s approach – “you shall like the courage, uniquely his own, of apainter who does not wish to listen to anyone but himself.”If Bizinsky had remained in Paris his opposition to current schools of abstraction might have ledhim to work in the vein of expressive social realism; certainly one aspect of Bizinsky’s work – the relatively violent distortions of some figural compositions – suggested such a direction. On the otherhand, any kind of modish existential despair was fundamentally antithetical to Bizinsky’s cheerfultemperament, coloristic gifts, and distrust of fashionable trends. In the event, Bizinsky remainedalone; and it was thus a certain American quality in his post-impressionist style that the critics intuited. They found this Americanism in a pictorial language of great spaciousness and clearness.The influence of French expressionistic naturalism was sophisticated development of Bizinsky’s youthful American regionalist sympathies; and bursting through the refinements of lateSchool of Paris painting was the artist’s spontaneous appetite for the intensities of French fauvism asfed by memories of the colorful Georgian countryside. Perhaps too, it was not strange that Bizinsky’sBrittany and Paris scenes were thought to emanate “a California sense of light and space.” The comment was prophetic. By 1951 Robert Bizinsky was back in the States and settled in Los Angeles.Bizinsky originally arrived in Los Angeles as the recipient of scholarship from the Huntington Hartford Foundation. The secluded art colony in the mountains near Pacific Palisades had been established in 1948 and was an important part of the Los Angeles scene for almost twenty years. Although Huntington Hartford was toturn against extreme modernism, he wasappreciative of Bizinsky’s post-impres-sionist and always considered him to bea leading American painter.When Bizinsky married in 1952, hechose to make Southern California hispermanent home. He and his wife, theformer Eleanor Anita Guggenheim, settled in Brentwood where Bizinsky devoted himself to painting, teaching,and traveling – extensively in Mexico, Central and South American, and theUnited States where his established habitof sketching the local terrain deepenedhis love of landscape painting. He frequently exhibited in the communityand in the wider Southern Californiaarea, and he was pressed into service as a lecturer and juror. Bizinsky was also the guiding light of the Westwood Art Association during its early, active days when commercialgalleries presenting Los Angeles artists were practically nonexistent; he served as its President in 1955.Accustomed to the lively ateliers and sophisticated talk of Paris, Bizinsky found 1950’s Los Angeles to be unsympathetic both to non-European modernism and to local talent of all persuasions. But as the 1960’s exploded to make of Los Angeles a true art center, he found himself situated between the older generation of pioneering Hard Edge abstractionists and the brash, newgeneration of assemblagists, Pop artists, and home grown Surrealists whose explorations appeared superficial to him. Thus Bizinsky chose to teach privately in his Brentwood studio to avoid the 19

exigencies of the commercial gallery situation and to give independent showings of his work to themany appreciative collectors of his landscapes, seascapes and figural groups. His Paris training gaveBizinsky a firm grounding in the academic basics and left him unmoved by what he called contemporary “fads”. As a mature painter and high respected teacher, Bizinsky’s well-expressed esthetic credo harks back to a fauvist heritage: To me a good painting is one that is a complete statement of the personal lyricism of the highly developed individual who is able to feel and see thatwhich is around him and able to put it into paint so vividly that it reaches a high peak and sustainsitself instead of being sustained by outside forces. 1Certainly too, Bizinsky’s personal courage was immense. When a laryngectomy robbed him of his speech in 1969, he refused to stop working: painting was the solace and the vehicle of recovery. He searched to “discover all the possible harmonies . . . trying to arrive at a psychophysical state of equilibrium.” 1When death came in 1982,Bizinsky left behind an impressive oeuvre that reflects this harmony and equilibrium.Besides the oil paintings there is an extensive group of drawings, watercolors and pastels fromboth the Paris and the Los Angeles periods. Drawings employing a sensitive and tender line contrastwith occasional essays in cubist fracture and bold energy. A large compilation of lively, intenselyhuman pen-and-ink sketches is of particular interest; they are on-the-spot creations of the army artistat work in England, North Africa andthe Mid-East. Most notable is a seriesof sketches depicting soldiers at theirdaily activities during a dangerousearly crossing of the Queen Mary in1942.But finally it is Bizinsky’s painting that impresses with its sincere feeling, its coloristic verve and(in the case of the 1951-82) work) itssecure place in the distinguished California landscape tradition. Theartist is revealed as an expressive naturalist who chose to sidestep the more extreme developments of post-1945. Transcending the merely regional, he fused a solid School ofParis training with a highly personal response to locality. The independentpath of Robert Bizinsky achieved alyrical post-impressionist vision thatcontinues to reward contemplation.1) Robert Bizinsky. All quotations, unless otherwise indicate in text, are Bizinsky’s. Source material is located in the Bizinsky Papers, Brentwood.2) Ossip Zadkine, in John Stanton, “The New Expatriates”, Life 22 Aug. 1949, p. 87.20

8. Walking Her Dogoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

22

9. Summer Day in the Parkoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

10. Cafe duVal, Rue de Banlieueoil on canvas, 20 x 24.

25 “Bizinsky is an ardent colorist and a tenderobserver of our streets and way of life”— Maximilien Gauthier, Les Noubelles Littéraires, 1949

26

11. Montmartre-Moulin de la Galetteoil on canvas , 24 x 20.

12. Couple on a Park Benchoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

29 “. . .you can put this down and sign it Zadkine:There are boys here now that the States are goingto hear of – Paul England and Kenneth Nolandand Robert Bizinsky”— Ossip Zadkine, 1949

30

13. Plowing a Fieldoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

14. Dome Tobacoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

33“Bizinsky has a sense of light and spacehe translates Brittany scenes into his spacious language and his Paris landscapes have the American clearness”.— Barnett D. Conlan, Continental Daily Mail 1948

15. A Brilliant Spring Dayoil on canvas, 21 x 31.

16. Bird's Eye View, South of Franceoil on canvas, 24 x 18.

37

3817. Cafe de Paris, Provincial Townoil on canvas, 18 x 24. “We will admire the courage so rare of a painter who is willing to listen only to himself”— Philippe Soupault, 1949

18. Strolling Parisiansoil on canvas, 20 x 23.

41

42 “Great natural ability and is endowed with a splendid imagination”— Frank Vincent Dumond. Art Students League, New York – 1946.

19. A Couple at a Fountain, Parisoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

20. Paris Book Stallsoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

45

46 “I have not only enjoyed seeing Mr. Bizinsky’s paintings but have beenmost interested by them. I hope that youwill on no account abandon this nobleprofession”— Ambassador to France, David E.K. Bruce, 1949.

21. Jardin de Montmatreoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

22. Au Vieuxoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

49

50 “Bizinsky has beautiful qualities, afresh touch, a solid way of paintingwhich warrants the attention of all the collectors"— Jean Bouret Les Arts, June, 1949

23. Book stalls along the Seineoil on canvas, 24 x 15.

24. Cafe Terrace, Montmartreoil on canvas, 18 x 22.

53 “Robert Bizinsky is one of the finestyoung artists of our time”—Atlanta Constitution

54 “Bizinsky, whose recent landscape exhibition at Galerie Castelucho drew toppraise from Paris Art Critics”— LIFE, August, 1949

25. Luxemborg Gardensoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

26. Place du Tertre, Montmartreoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

57 “All of his work bears a distinguishabletemperament”— John Devouly, New York Herald Tribune, Paris Edition, 1949

58

27. Early Spring in Parisoil on canvas, 20 x 24.

28. Booksellers on the Quayoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

61 “Robert Bizinsky’s work has a quality which stimulates greatly. I can only describe it as a communication of delight. He can make you share his appetite for a scene, so that you wish you could eat it.Looking at his paintings of the South of France, I think:That’s how those houses, that waterfront seemed to mewhen I first saw them, as a young man. Or at any rate,how they ought to have seemed to me. I suppose Bizinskygets this effect by his highly evocative use of color. But be-hind the brightness, there is something more mysteriousand sophisticated, something that suggests the richness of classical Persian art. I should like to live with such pictures. Because then I know, I should be able to live inside them. They can be entered.”— Christopher Isherwood, 1951

62

29. Rowboat on the Lake, Bois de Boulogneoil on canvas, 18 x 24.

30. Vineyardoil on canvas, 20 x 24.

“I am deeply impressed by the picturesand comment” - “And certainly the material deserves public attention and approval”.— Edward L. Bernays

Musee Du Louvre and the Seine, ParisFountain St. Paul de VenceWalking Her DogCafe duVal Rue de BanlieueSacre-Coeur from the rue de MontmarteOutdoor CafeAcross from a Cafe, ParisSummer Day in the ParkMontmartre-Moulin de la GalettePlowing a FieldWoman and Child, Tuileries GardensCouple on a Park Bench

South of FranceStrolling ParisiansParis Book StallsAu VieuxA Brilliant Spring DayCafe de ParisA Couple at a Fountain, ParisJardin de MontmatreBookstalls along the SeineLuxemborg GardensDome TobacCafe Terrace, MontmartrePlace du Tertre, Montmartre

VineyardRed Roofs, South of FranceCultivated Gardens and VillageWoman and Child on Park BenchRowboat on the Lake, Bois de BoulogneSt. Paul de VenceHarbor in BrittanyGardens South of FranceTwo Fishing Boats in Harbor, BrittanyFrench HarborEarly Spring in ParisBooksellers on the QuayVillage, South of France

The Blue UmbrellaVillage, South of FranceTown and ChurchMen at Work at the HarborA Village ChurchA la Ville de ParisA View to a ChurchNude Woman and Child in a ParkTwo Men on the Quay Overlooking A HarborHarbor SceneAfternoon in the ParkHarbor Scene, BrittanyPlace Furstenburg

Luxembourg GardensRue BouleIle de la Cite, ParisAlong the SeineStreet Corner in ParisBridge on the SeineSacre Coeur, MontmarteA Suburb of ParisArtist at Work, Place du TertreTwo Women on a Corner, ParisSt Germain des PresBusy StreetSmall Square, Paris

Quais of the SeineBois de BoulogneCrossing a Paris StreetEarly Evening in the ParkTuileries GardensActivities in the ParkOutdoor CafeWoman and Child on a PathHotel de Sens, ParisCafe-Restaurant, MontmartrePlace du Tertre, Sacre CoeurDu Pothius PontoiseCafe-Restaurant, Montmartre, Winter,

Footbridge over a Venetian CanalBridge Near the TiberOn The Way to ChurchStreet SceneBlue Gondola and Bridge, VeniceVenice, View of St. Mark’sRed and Yellow UmbrellasHouses Along a RiverSummer FieldsOutdoor CafeChamps de Mars and the Eiffel TowerThe Red Umbrella, VenicePark SceneWorking in a Field

354 Woodmont Road | Milford, Connecticut 06460203.877.1711 | shannons.comPRIVATE SALES