Return to flip book view

Message

Dr. Celia Banting

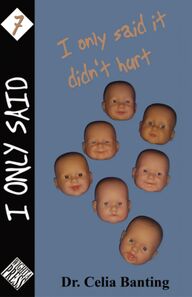

Copyright © 2008 by Dr. Celia BantingAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, in-cluding photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to the following address: Wighita PressP.O. Box 30399Little Rock, Arkansas 72260-0399www.wighitapress.comThis is a work of ction. Names of characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination and are used ctitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataBanting, CeliaI Only Said It Didn’t Hurt/Dr. Celia Banting – 1st Editionp. cm. ISBN 9780978664862 (paperback)1. Therapeutic novel 2. Cutting 3. Self-harm 4. Suicide preventionLibrary of Congress Control Number: 2007930367Layout by Michelle VanGeestCover production by Luke JohnsonPrinted by Dickinson Press, Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA

Issues addressed in this book:Inter-generational behavioral patterns Care-giver rolesCutting and self-harmPersonality developmentFive parts of the selfTaking control of the selfCorresponding behaviorsAssimilated InjunctionsInnate nurturingAttention seeking behaviorRaising self-esteemMaintaining safe boundariesEffective communicationStress managementSelf-soothingAchieving true intimacy

Also by Dr. Celia Banting…I Only Said I Had No ChoiceI Only Said “Yes” So That They’d Like MeI Only Said I Couldn’t CopeI Only Said I Didn’t Want You Because I Was TerriedI Only Said I Was Telling the Truth• • • •Available after April 2008…I Only Said I Could Handle It, But I Was WrongI Only Said I Wasn’t HungryI Only Said I Wanted To Kill Myself; I Didn’t Really Mean ItI Only Said Leave Me Out of It

Dedicated to Erica Elsie and to precious Destiny for her courage and faith in trying this therapy in order to change her own destiny. Also dedicated to sweet Lauren for her enduring pursuit of romance.

AcknowledgmentsMy grateful thanks go to my proofreader and typesetter, Michelle VanGeest, who frees me from my dyslexic brain, and replaces my mother’s voice. Thanks to Bev, my stray-word spotter, too. I thank my wonderful husband, Des, for the inspi-ration and support he gives me. Thank you to Luke and Sam for their faith, inspiration and talent. Thank you to Helen and Dave, and Moya and Tony for their faith and support—and especially Moya who introduced me to Beringuer newborn dolls and the world of “reborning.” Thank you to Susan Harring and Ron Woldyk for their reliability and professionalism. Thank you to my dear friend Vicki for her guiding sense of style. Thank you to all my psychotherapy tutors and colleagues at the Metanoia Institute, London, for teaching me about hu-man nature, psychopathology, growth and recovery. My utmost respect goes to the late Dr. Eric Berne, and all the innovative thinkers who came after him, and hope that he would approve of the re-labeling of his ego states to help clarify his theory in order to help teenagers who just didn’t “get it.” Thank you to Mr. Philip Pullman, author of The Golden Compass, for kindly agreeing to allow me to use his concept of an externalized soul for therapeutic purposes. I thank the good Lord for giving me a lively imagination, and I also thank my parents for moving to the Isle of Wight, “the land that bobs in and out of view, depending upon the sea mist.”

11É ÑChapter One “Don’t be such a baby, Marsha,” Dad snaps at me. “You’re fteen, for heaven sake.” I don’t dare answer back. I learned my lesson years ago when I was little. Why does he have to be so mean? “You’ll be okay, honey,” a nurse says. “Here’s something for the pain.” She injects something into the needle strapped to my hand and passes me a tissue. I wipe my nose clumsily with my free hand. “Appendicitis is very painful, sir. She is not being a baby.” I give her a bleak smile for sticking up for me. Dad glares at her and waits until she walks away before letting me know what he thinks again. “Well, tears are for babies. My father used to tell me…” Here we go, I think to myself, “…how his

12É Ñmen suffered dreadful injuries and never so much as squeaked.” I’m so sick of hearing about his father, my grandfather. I know I shouldn’t think like that, and I should be grateful for the sacrices his generation made for us. I am; I’m just tired of having Dad go on and on about it every minute of the day. I don’t know how long my grandfather was in the military; I kind of tune out when Dad starts on about it. But I know that he told Dad story after story, in the same way I’m expected to read fairytales to my little brother and sister, Casey and Shelley. It doesn’t matter what anyone’s talking about, it’ll get Dad started, and he’ll say, “Oh, that reminds me of something my father told me,” and off he’ll go. “…One bomb blew his leg off,” he says. “Are you listening to me?” “Sorry, Dad,” I wince with pain. “I feel dizzy. I think the medicine’s kicking in.” He looks irritated with me but I close my eyes, thankful that the edges of the biting pain in my stomach are blurring as he speaks. His voice blends into the sounds of the hospital beyond my bed, and I drift away. Fragmented thoughts oat into my mind. Where’s Mom? It hurts that she couldn’t be bothered to come to the hospital with me. Too drunk, I guess. Who’s going to look after Casey and Shelley without me

13É Ñthere? Mom won’t bother and Dad’s too busy. But as the thoughts blend together, I drift further away and everything goes black.• • • • I wake up with someone squeezing my nger so hard that I gasp. “Good girl, breathe! There you go.” I choke as something is pulled out of my throat, and as a feeling of panic threatens to suffocate me, I suck in air, panting. I don’t know where I am. My world is just six inches from my face. It’s lled with someone shaking me, and telling me to breathe deeply. I can hear alarm bells going off. I gasp for breath like someone drowning, and the alarm bells stop. “Good girl. Good job. She’s ne,” I hear some-one say, and I’m aware that whoever was by my bed has gone. Time oats in and out of my consciousness, and it doesn’t really settle on me until my stomach rumbles. It’s time for food. I wake up in a ward that has another person in it, who is snoring. I try to sit up, but a sharp pain shoots through me, and I op back down, whimper-ing. I don’t like this. I want it to go away. A nurse comes towards me with a ashlight. It must be nighttime. Dad’s not by my bed, but I’m not surprised.

14É Ñ “Are you okay?” she asks. “I think so. Where am I?” “You’ve had your operation and everything went well. You’re ne. You just need to recover, that’s all.” “I’m hungry,” I venture. “D’you feel sick?” she asks. I feel woozy, but I don’t feel sick. “No.” She walks away and comes back with a plate of buttered toast. She helps me to sit up. I wince, as the pain is awful. I have tears in my eyes. If I weren’t so hungry, I wouldn’t have bothered moving. Every mouthful is wonderful, and when I’m done, I slip back down into the bed and fall asleep.• • • • I’m home within days and back to my old routine, taking care of Mom, Casey and Shelley, and dodg-ing Dad’s military stories, telling me how thankful I should be. I limp around the house, my stomach cramping in pain, trying to do my chores. Mom’s on the couch, drunk, and the kids are outside in the yard. Dad’s out. It’s a weird thing. You would think that if your dad gets onto you enough about how cool the military is, then one day you’d want to experience it yourself, but it wasn’t like that with my dad. Even though he

15É Ñtalked about it all the time, he had never joined up. Dad’s mom, my Granny, said that he had “at feet,” whatever that meant, and was rejected. Mom told me that he’d tried to join the National Guard several times, but he was always rejected. But Dad wasn’t deterred; he lived out his military life in our home and backyard. He had Casey march-ing up and down the path with a broomstick sticking up over his shoulder. “Attention!” he would shout, and Casey would come to a stop abruptly. And with a squeaky six-year-old voice, he would shout, “Sir! Yes, sir!” Sometimes when Casey got his steps wrong, Dad would yell at him and he’d cry. “Stop crying,” Dad would shout. “Boys don’t cry. By the left, quick march,” and Casey would sniff, as he started to march up and down the path again. “Left, left, left right left.” I felt sorry for him, but I didn’t say anything. I was just glad that Dad wasn’t picking on me. Everything changed for Casey when Dad got a letter from the National Guard, saying that he’d been accepted because the situation in Iraq was getting worse, and the government needed more men. I hear him singing in the bathroom as he gets ready to leave. He’s glad to go, having waited so long to live the life his father has talked about. I know that Casey is glad Dad’s going; Shelley is

16É Ñtoo, but Mom cries and cries. As he heads for the door, Dad says, “Lillian, stop it. You know I can’t handle seeing you cry. Stop it. You’ve got Marsha here to help you. Get control of yourself, for pity sake.” Mom drapes herself around him as he opens the door, and he pries her hands off him as he steps outside. He doesn’t kiss her, or wave, as he walks down the path, and he totally ignores me. “Bye,” I say, feeling nothing. “Come inside, Mom.” “Leave me alone,” she snaps at me, as she heads towards the liquor cabinet. Well, excuse me, I think, going to my room. I turn my music up loud to drown out her wailing downstairs, and I watch the kids outside, playing quietly in the yard. From my window I can see the neighbors’ kids yelling and screaming in their yard, and it strikes me how quiet my brother and sister are compared to them. I guess I’m quiet, too. The kids at school say I am, and sometimes I hear them call me a loner. I don’t know why it is. I like people and I’m nice to them, or I think I am, but I just don’t have anything to say to anyone. It’s hard to feel excited about the things they do. In fact, now that I think about it, I rarely feel anything at all. Most of the time I feel numb, and I have felt that way for ages. Ever since I can remember, I wasn’t allowed to

17É Ñshow any feelings. Even when I felt angry because Dad picked on me and Mom expected me to do ev-erything when she was drunk, I wasn’t allowed to show my feelings. No one told me that, but it’s just something I knew inside; it was like a silent rule in our family. When I was little, Granddad would shout at me. He’d say, “Children should be seen and not heard,” and if I ever cried, he looked at me as if I were something disgusting. He’d tell Dad to give me something to cry about. Dad would stand over me and say, “You can quit that nonsense; it won’t work with me, so you may as well go to your room. You can come out when you quit being such a baby.” “You tell her,” Granddad would say. I always knew that Granddad didn’t like Mom. I heard him saying bad things about her once, when he didn’t know I was listening. “Why d’you put up with her nonsense, son? Be the man of the house. If she were my wife, I’d put her in her place. I can’t stand people who can’t control themselves; they’re so weak.” It’s true that Mom couldn’t control the way she felt; she was always crying and getting hysterical. Dad shouted at her all the time, and I decided that I was never going to be like her. I wasn’t going to show my feelings like she did. I didn’t have to worry, though, because I didn’t seem to have any

18É Ñfeelings. Mom’s parents lived so far away that we rarely saw them. Dad never actually said bad things about them, but I could tell that he didn’t like them. When Granddad came to stay, I heard him ask about them and say, “It’s just as well,” when Dad said that they couldn’t afford to travel. Granny seemed to stick up for Mom’s parents, though. “Perhaps Lillian would be more, um, stable if her parents were nearer and able to help her.” Granddad sounded just like Dad. “Don’t be stu-pid, woman, where d’you think she learned how to be so useless? Oh, sorry, son,” he added as an afterthought. I’d crept back to my room feeling confused. Mom had told me over and over how she and Dad met. It had been my favorite story when I was little, and she was sober. She’d make Dad sound like a hero, and she was his princess. “He was so stiff, so upright and proper; so differ-ent than me,” she would giggle. “I think I confused him. He called me his ‘little buttery’ because I would it about. Sometimes he’d scratch his head when I slid down the slide on a kids’ playground, as if he couldn’t quite gure me out. But he seemed to want what I had, and I forced him to climb to the top of the slide and slip down after me. He’d laughed and said that he’d never had so much fun.

19É ÑYou should have seen me in my wedding dress; I was like a fairy princess.” She’d show me photos of them on their wedding day, and I knew that everything she’d told me was true. Dad stood there, stiff, rigid and proper, while she clung onto his arm with her leg bent up behind her, pulling a goofy face. The family photo showed Dad’s parents standing there as rigid as he was, and Mom’s parents laughing, dressed in wild clothes. I grew up not knowing Mom’s parents, as Mom and Dad had moved soon after they got married to live nearer to Dad’s parents. I was born ten months later. When I look at Mom as she is now, she’s nothing like the person she was in her wedding pictures. I don’t know what’s happened to her. Maybe it’s the alcohol. I don’t know. I shake my thoughts from my head, and I see Casey and Shelley sitting quietly in the garden, ig-noring the noisy kids next door. I guess all three of us are quiet, not a bit like Mom, who is very noisy. Mom hammers on my door. “Turn that racket off,” she says, and I hear her dissolve into tears. “What about my nerves? Don’t you care about me at all? My husband’s just gone off to ght overseas, and all you can do is make my headache worse.” I don’t open the door because I don’t want to see her drunken face, begging me to make things

20É Ñbetter for her. I can’t cope with her when she’s like this, so I turn my music off and throw myself on my bed. I try to ignore the sounds of her sobbing as she goes down the stairs. My heart races. She makes me feel guilty. Thanks to me, she’s more upset than she was when Dad left half an hour ago. Something inside me festers, as I hear the neighbor’s kids laughing and being loud. My brother and sister are in the yard, still quiet, and I’m lying here on my bed, robbed of my music because Mom has a headache. It doesn’t seem fair somehow. I fall asleep listening to the sounds from our neighbor’s garden and only awake when there’s a knock on my door. “Marsha, wake up. We’re hungry.” I glance at the clock on my bedside cabinet. Heck, I’ve been asleep for two hours. I’ve got to get dinner. I get up and open the door. The kids come into my room. Shelley looks anxious. “Mom’s sick,” she says. I know what that means. She’s not sick at all. She’s drunk. The look on their little faces turns my stomach. They didn’t ask to have such crappy parents, so I put on a happy face to hide the emptiness inside me and tell them to follow me downstairs. Mom’s on the sofa watching her soaps. “Shut up,

21É ÑI can’t hear,” she snaps, when I ask the kids what they want for dinner. I feel my jaw tense. I lower my voice and ask them again. They say, “Fries.” I know that I’ll get into trouble if I don’t make Mom something to eat, so I go over to her and ask her what she wants. She looks at me as if she’s seeing me for the rst time, as if I’m a total stranger in her house. “Um, what?” Then she grabs me by the wrist. “I’m hungry. My husband’s left me. You’d be upset if it happened to you.” I try to bite my tongue, but I can’t. “Dad hasn’t left you; he’s gone overseas to ght.” But as I say it, I can’t help but think that she’s got it right and I’ve got it wrong. Dad was desperate to leave, and he didn’t even give us a second glance as he hurried off to fulll his dream. I pull my hand away and stand tall. “What d’you want to eat?” I ask her again, show-ing no emotion at all. She sobs. “You’re so like your father,” she cries. “So cold.” Great! Thanks! “So, what d’you want to eat?” She sits up, groaning loudly, and suddenly she looks like an actor on a stage, but one that’s awful — the sort who’s told not to give up their day job. “Oh, I feel so ill,” she says, wiping her brow. “I can only manage something small.”

22É Ñ But as usual, she eats everything I give her, and that’s a lot. I want her to fall asleep, because only then will she give me a break. Finally she’s asleep on the couch and it’s quieter. We’re quiet, as we don’t want to wake her. Even though Casey and Shelley are only little, they’ve learned to be quiet around Mom. The three of us sit in the kitchen, munching fries, dipping them into tomato sauce. They’re good, and I’m starving. I haven’t bothered to cook much to-night, as Dad’s not here. Normally he’d want a full meal, the type his father used to get when he was in the military — wholesome food — but I didn’t have time tonight. The kids don’t mind, though; they’re happy that Dad’s not here forcing them to eat their vegetables. The house seems different in the morning with-out Dad barking at us to get ready or we’ll be late. “You know how I hate tardiness,” he’d say. I get the kids up and give them cereal, and we leave the house at the same time that we would have, had Dad been here nagging us. I don’t bother to say goodbye to Mom, because she’s still in bed, sleeping off a hangover. As the days turn into weeks, every morning’s the same. I get the kids up and off to school, and Mom’s in bed, oblivious to the three of us in the house. When school nishes, I pick up Casey and Shelley and we trek home again.

23É Ñ One day Mom’s on the couch with the television blaring. She’s holding a letter in her hands, and she’s crying. “What’s the matter?” I ask. She looks more lost than usual. “Mom’s coming to stay. My dad’s left her,” and suddenly out of nowhere, she screams at me, “Get this place cleaned up.” The kids look scared and go out into the back-yard. I grit my teeth, wanting to yell back, but I know it’ll do no good when she’s this way. I dump my schoolbag down and start picking stuff up. “Don’t touch that,” Mom yells. “I want that next to me. What’s wrong with you? Pick up the mess, not my magazines.” She starts crying all over again, and I feel locked in a place where it’s okay for her to pick on me but, because she’s in pieces, I can’t stick up for myself. There’s a festering resentment growing inside me with nowhere to go. I can’t let it out, for if I did, Mom would take it out on the three of us. There’s junk everywhere. Since Dad left, no one’s cleaned the house and it’s a pigsty. I’ve coped with getting the kids and myself to school, feeding us all, and doing laundry, but I haven’t had time to clean up. As I look around me, I don’t know where to begin. Part of me wishes that the kids were older and

24É Ñcould help me, but right now I’m glad they’re out-side, away from Mom’s hysteria. “I hope there are clean sheets,” Mom frets. “Go and check, will you?” I stop picking up Mom’s dirty plates that are all around the couch, and I go upstairs to look in the linen closet. “Make up the spare bed in your room,” she calls up the stairs. This time I answer back. “What? No! She can’t stay in my room.” Mom bursts into tears again and corners me by breaking down. “Why are you arguing with me? Are you deter-mined to hurt me? Just do as I ask, will you?” She walks away sobbing, saying, “Hell, that child is just like her father, cold as ice, and doesn’t care about anyone but herself.” I want to smash her to pieces, to tell her she’s so wrong about me. I care about everyone. It’s me that keeps the family together. How dare she say such awful things? But I can’t say anything, because she’d just disintegrate before my eyes and then blame me for it. So I grit my teeth, yet again, and make up the spare bed in my room for the grandma I’ve never met. I look around my room. It’s the only safe place I have in this house, where I can go when Dad’s criti-cism of me and Mom’s hysteria wear me out. But

25É Ñnow I won’t have anywhere to go, as there’ll be a stranger invading the only space I have. My stomach churns, and it feels as if there’s a monster festering and growing inside my intestines with nowhere to go. When the bed’s made, I go back downstairs. “Did you put fresh towels on Grandma’s bed?” Mom demands. “No.” “Well, go and do it,” she snaps. “Why d’you have to be told everything? You’re making me ill, Marsha, don’t you realize?” I stomp upstairs again, the monster inside me growing by the second. Why can’t she do it? Why do I have to do everything? I put three towels and a washcloth on Grandma’s bed and go back downstairs to vacuum the living room. “Be careful,” she shouts, as I suck up something that rattles. “You’ll break it.” I switch it off and shake the vacuum. A piece of glass drops to the oor. Mom must have broken a glass at some time and didn’t pick up all the pieces. She’s nagging me about breaking the vacuum, yet she doesn’t care about whether the kids would have stepped on it and cut their feet. I walk out of the room and drop the shard in the trash, my jaw clenched as I struggle to control myself. She pours herself a glass of whisky and takes a gulp with shaking hands. I start the vacuum again

26É Ñand push it this way and that, as Mom sits on the couch, drinking. She rubs the side of her head and yells over the sound of the vacuum, “Can’t you hurry? My head’s killing me.” It might not hurt so bad if you’d just stop drink-ing, I think, but I don’t say anything. Eventually I’ve nished and it looks so much bet-ter. If I didn’t feel so battered by Mom’s tongue, I’d have felt pleased with myself. Mom is like a cat on a hot tin roof as she paces the oor, glancing at the clock, and looking out of the window. “What time is she coming?” “Any time now,” Mom slurs. “Start making din-ner.” “What d’you want me to make?” “Oh, I don’t know. What is there?” Mom has no idea what’s going on in our house, and the fact that she doesn’t know what’s in the fridge proves it. I search for something to cook, but there’s only snacky stuff, not anything with which to make a proper dinner. I tell her and she gets all ustered. “Why didn’t you tell me we needed more stuff?” she cries. She shakes her head, as if she can’t be-lieve how stupid I am, and goes to her purse. “Here, go to the store and buy some pork chops and stuff to make a salad,” she says, handing me

27É Ñtwenty dollars. “And hurry up. Grandma could be here any minute, and we won’t have anything to give her to eat. Honestly, Marsha, can’t you see that I’m not well? You’ve got to do better.” I snatch the bill out of her hand and slam the door behind me. The monster inside me festers and grows, churning inside my intestines. I put my head down as I pass other kids who go to my school. It doesn’t seem fair that they’re able to hang out and have fun, while I’m stuck inside trying to make ev-erything right for a mom I can’t please. They’re still there when I walk back to the house with two full grocery bags. I bought some chocolate milk for the kids; I know they love it. But now I wish I hadn’t, because the bags are heavy. As I open the door, I can tell that Grandma has arrived because Mom’s giggling like Shelley does when someone tickles her. She sounds like a silly kid. I walk into the living room, and standing there is a woman who looks like an older version of Mom. She’s got too much makeup on, which is smudged, as she’s obviously been crying, and she’s got long hair that’s been dyed blond. There’s a dark line in the middle of her head where her roots are show-ing. “Ah!” she wails, holding out her arms as she comes towards me. “You must be Marsha.” I stand there stify, with the bags by my side making my shoulders ache, as she throws her arms

28É Ñaround me. I feel like choking as she’s wearing too much perfume. She engulfs me and I pull my head back, trying to catch my breath. “Hello,” is all I can think of to say. When she lets go of me, I go into the kitchen and dump the bags on the counter. I can hear Mom saying bad things about me. “I’m sorry there’s no dinner made. I have to get after Marsha all the time. You’d think she’d help more, what with Dad being away.” She bursts into tears and Grandma puts her arms around her, while I seethe in the kitchen. I slam the pork chops onto the grill, as the monster inside me writhes, begging to be released. Then I slam the let-tuce on the chopping board and reach for a knife. Grandma comes up behind me and says, “Mar-sha, you really should help your mother more. Can’t you see that she’s having a hard time? I’d help her myself if I weren’t having a hard time, too.” My head starts spinning with the injustice of it all, as this woman, who I’ve never met before, tells me I should do more, without knowing that I do every-thing. In an instant I hate her, and my guts churn even harder as she, too, bursts into tears. “My husband, your grandfather, has just left me after all these years,” she sobs. She falls to pieces in front of me, as Mom’s in the living room already in pieces, and I want to scream. But as always, I say nothing. I chop the lettuce and

29É Ñdump it into a bowl. “When you’re older, you’ll understand and perhaps you’ll show a little more compassion,” Grandma says. “You need to support your mother, not make her life harder.” I grab a tomato, and it almost squashes in my hand as the monster inside me screams to be re-leased. I take the knife and cut the tomato into slices with such a force that the knife slices across my nger. Bright red blood oozes out of me and onto the tomato. Grandma shrieks, “Oh, no. Lillian, she’s cut her nger, and there’s blood all over the food.” “Oh, now what,” I hear Mom say. But that’s the last thing I hear either of them say, even though I’m vaguely aware that they’re fussing around me, for something weird happens to me. My body is bathed in a warm feeling as my n-ger smarts. I can actually feel something, pain, yet it doesn’t really hurt. It’s strange. But something even more amazing happens. The monster inside me, that has festered and grown and was about to burst out of me, coils back down, sleeping peace-fully in my intestines.